Introduction

Thyroid cancer (TC) encompasses several pathological types, notably papillary thyroid cancer (PTC), follicular thyroid cancer (FTC), medullary thyroid cancer (MTC), and anaplastic thyroid carcinoma (ATC). While PTC accounts for the most common type, ATC, despite representing only 1–2% of all TC cases, is recognized as the most lethal and treatment-resistant endocrine malignancy. Despite sharing a common cellular origin, these two subtypes differ markedly in their clinical trajectories, response to therapy, and immune profiles. Even though ATC is characterized by poor prognosis and pronounced resistance to conventional therapies, it is surprisingly transiently responsive to immunotherapies that prove less effective in advanced PTC. A potential determinant of these divergent clinical behaviors may lie within the differential tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) of these cancers. Comprising immune cells, stromal elements, and signaling mediators, it evolves dynamically during tumor progression and metastasis. Recent advances in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) and spatial transcriptomics have revealed that each subtype of thyroid cancer TIME harbors a distinct immune and stromal composition, functional state, and spatial organization. With the increase in understanding of TIME, the treatment of advanced thyroid cancer might undergo significant evolution, from drugs that addressed genetic mutations on signaling cascades to the idea of combinational immune therapies that can integrate both cancer genes and immune cells sitting in the surrounding of the tumors.

Building on recent work [1], which outlined the immune cell composition and therapeutic relevance of TIME in thyroid malignancies, this review aims to extend the discussion by focusing on the emerging players. We summarize distinct roles of macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and cancer-associated fibroblasts with reference to the latest scRNA data. We also explore novel immune checkpoint pathways beyond the conventional PD-1 and CTLA-4 axes.

Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs)

TAMs originate either from tissue resident macrophages or differentiation of blood monocytes as a consequence of multiple stimuli from tumor cells. In TIME, TAMs are classified as M0-, M1- and M2- like TAMs. Classically, M1 TAMs support tumor rejection by producing IFN-γ and TNF-α and by presenting tumor antigens to drive T-cell responses. Conversely, M2-like TAMs foster an immunosuppressive milieu, characterized by elevated PD-L1 and secretion of IL-10, TGF-β, and IL-4. However, this traditional M1/M2 macrophage paradigm fails to capture the complexity of TAMs in TIME. Han et al. [2] recently investigated the tumor microenvironment of thyroid cancer and found a significant increase in the presence of M2 macrophages in ATC compared to PTC. Interestingly, the proportion of M1 macrophages, remained largely equal. This finding suggests that the focus of research should shift from trying to convert M2 macrophages into M1 macrophages to concentrating on guiding M0 macrophages to differentiate into the M1 type instead. In this context, a recent study by Huo et al. [3] found that the protein Apolipoprotein E (APOE) plays a key role in regulating macrophage polarization within the PTC TIME. Specifically, APOE appears to drive M0 macrophages toward an M2 phenotype via the PI3K/AKT/NF-κB pathway, and silencing or inhibiting APOE could be a therapeutic strategy to promote the differentiation of undifferentiated M0 macrophages into the anti-tumorigenic M1 phenotype. While the study verified macrophage phenotype by classical macrophage markers like CD68, arginase etc., with the advent of sophistication in scRNA sequencing and spatial profiling, it’s clear that TAMs in thyroid tumors exist along a spectrum of states rather than conforming to binary classifications. A recent study by Liao et al. [4] used spatial transcriptomics to identify distinct M2-like macrophage subsets including Mac-5 SPP1+VCAN+MMP9+ (enriched across all thyroid cancer types at tumor leading edges) and Mac-1 (CD163+VEGFA+IL10+ specifically enriched in leading edge of anaplastic thyroid carcinoma), demonstrating that macrophage subtype and function is profoundly influenced not just by spatial localization but also by the cancer type. This spatial and functional complexity necessitates that therapeutic approaches must evolve from broad-spectrum to precision targeting strategies. Considering other cancers, for instance, in breast cancer, the presence of M2-like TAMs co-expressing CD206, MORC4, and SERPINH1 have been correlated with improved patient survival [5]. Moreover, in cutaneous melanoma, a distinct subset of CD206+ macrophages were found to act as effective antigen-presenting cells (APCs), which was also associated with better overall survival outcomes [6]. Therefore, the conventional paradigm of TAM depletion, inhibition of TAM trafficking, or M2→M1 reprogramming in solid tumors warrants reconsideration. Instead, future interventions should focus on subset-specific reprograming strategies (such as shifting Mac-1 toward anti-tumor macrophage phenotypes like those expressing CD206 or selective inhibition via Colony Stimulating Factor 1 Receptor, CSF-1R, blockade in ATC), and recognition of ontological diversity between monocyte-derived macrophages and tissue-resident macrophages that might respond differently to therapeutic interventions.

Tumor-Associated Neutrophils (TANs)

Tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) are now recognized as key players in the thyroid cancer immune microenvironment. Like macrophages, within the TIME, neutrophils acquire plasticity, polarizing into anti-tumor N1 or pro-tumor N2 states, influenced by signals such as that of TGF-β. In PTC and ATC, thyroid cancer cells secrete IL-8/CXCL8 to attract neutrophils via CXCR1/2, promoting TAN recruitment and TIME suppression. Neutrophil to T lymphocyte ratio has been used as a prognostic marker for radioactive iodine therapy and known to be increased in undifferentiated cancer compared to differentiated cancer; however, with more understanding of neutrophil heterogeneity this ratio has limited significance. While dedicated scRNA-seq profiling of thyroid-infiltrating neutrophils remains limited, recent studies using bulk sequencing and flow cytometry identified significant neutrophil heterogeneity categorized into high-density neutrophils (HDN) and low-density neutrophils (LDN), with HDNs being decreased in thyroid cancer patients compared to healthy controls [7]. In this study the most striking finding was the predominance of immature neutrophils (CD10–) in advanced thyroid cancers, particularly in undifferentiated thyroid cancer (UTC) and stage IV disease, where participants show significantly higher proportions of immature HDN compared to those with DTC. These immature neutrophils, especially those expressing PD-L1, were associated with immunosuppressive functions and poorer prognosis. The differences across thyroid cancer subtypes were pronounced, showing higher neutrophil gene signatures in ATC compared to PTC, accompanied by decreased CD4+ memory T cells in aggressive subtypes. However, the study focused exclusively on circulating neutrophils, neglecting to study tumor-infiltrating neutrophils (TINs), which may have distinct functional roles within the tumor microenvironment. Potential confounding factors, such as patient age, comorbidities, or treatment history, were not fully addressed, which could influence neutrophil heterogeneity and clinical outcomes. Targeting neutrophils (particularly TANs and neutrophil extracellular traps [NETs]) is an emerging therapeutic strategy in thyroid cancer, especially for aggressive subtypes like ATC and advanced radioiodine-refractory differentiated thyroid cancer (RAIR-DTC). While dedicated thyroid cancer trials are still limited, several neutrophil-modulating agents in cancers have strong preclinical rationale for use in thyroid cancer. For example, Reparixin impairs viability, proliferation, and stemness of thyroid cancer cells, sensitizing them to chemotherapy [8]. Reparixin, is a CXCR1/2 (neutrophil chemokine) inhibitor, and it exhibited potential benefit in combination with Paclitaxel in HER-2 Negative Metastatic Breast Cancer (NCT02370238), advocating its evaluation in thyroid cancer as well.

Dendritic Cells

Dendritic cells are specialized antigen-presenting cells crucial for initiating and regulating immune responses, particularly in cancer, where they activate T cells to mount antitumor immunity. DCs are pivotal in bridging innate and adaptive immunity, capturing tumor antigens, migrating to lymph nodes, and priming T cells for antitumor responses. In progressive PTC, an expanded population of lysosomal associated membrane protein 3+ (LAMP3+) dendritic cells has been reported, correlating with advanced disease and poorer outcomes. These cells promote an immunosuppressive milieu by driving NECTIN2–TIGIT–dependent exhaustion of CD8+ T cells and enhancing CCL17–CCR4–mediated Treg infiltration [9]. In ATC, while a LAMP3-DC subset expressing PD-L1/PD-L2 and STAT1/3 is present and likely contributes to immune suppression, it is not the predominant myeloid population [2]. This observation is significant because it highlights that the mere presence or even activation of DCs is insufficient; their functional phenotype (e.g., whether they are pro-immunogenic conventional cDC1s or immunosuppressive LAMP3+ DCs) is paramount. Additionally, it might be worthwhile to analyze the transcriptomic profile of LAMP DCs in PTC and ATC as they could be potential biomarkers for aggressive/invasive/proliferating tumors. They are distinctly enriched in progressive PTC and ATC and significantly associated with reduced overall survival. This emphasizes the need for advanced phenotyping of DCs in clinical settings for accurate prognostic assessment and therapeutic guidance. Further LAMP3+ DCs could be potential therapeutic targets because they have shown to be upregulating MAPK pathways and STAT signaling and appear to be good candidates for combination therapy.

Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs)

CAFs are one of the most abundant stromal cell types within the thyroid cancer microenvironment. They arise from resident fibroblasts or via epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and are reprogrammed by tumor-derived signals. They interact directly with thyroid cancer cells through paracrine loops involving TGF-β, IL-6, CXCL12-CXCR4, and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)/c-MET axis. CAFs also exhibit heterogeneity in abundance and cellular identity across different cancer types. A mentioned study [4] revealed that fibroblasts in PTC and ATC are distinct from one another. While fibroblasts in both PTC and locally advanced PTC (LPTC) showed high EMT activity, those in ATC did not. ATC-CAFs showing high expression levels of genes associated with tumor invasion (MMP14, LOXL2, and PGK1) were found specifically enriched in ATC stromal components [2]. Also, CAF landscape in medullary thyroid carcinoma likely differs significantly from that in other subtypes due to its neuroendocrine origin and RET-driven signaling. CAFs also show functional heterogeneity across thyroid cancer types and are involved in different biological processes. For example, in PTC, fibroblasts are enriched for programs related to cholesterol homeostasis and apical junctions; in LPTC they align with angiogenesis and Notch signaling; and in ATC they exhibit interferon-α–responsive states [4]. CAFs also show sex-linked transcriptional differences (e.g., XIST, RPS4Y1), with female-biased CAFs favoring immune modulation and matrix remodeling, whereas male-biased CAFs track with greater tumor aggressiveness. Therefore, a more nuanced, subtype-specific therapeutic approach is needed, supported by robust biomarkers that can distinguish CAF populations and guide effective stromal type targeting. Currently, there are no approved therapies specifically targeting CAFs in thyroid cancer. However, ongoing clinical trials are evaluating radioligand therapies such as 177Lu-FAPI, which targets fibroblast activation protein (FAP). While 177Lu-FAPI achieved 83% disease control in a 12-metastatic-radioiodine-refractory-thyroid-cancer patient trial [10], its single-arm design and median follow-up of 8 months precludes efficacy conclusions. Notably, 40% of participants developed grade 3 lymphopenia, highlighting toxicity concerns absent in prior CAF-depletion models. Additional trials continue to assess the safety and efficacy of similar compounds, including 177Lu-DOTA-EB-FAPI, across a range of doses and treatment cycles (NCT05410821).

Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells (MDSCs)

MDSCs are a heterogeneous group of immature myeloid cells that potently suppress innate and adaptive immunity. In humans, two main compartments are recognized: M-MDSCs (typically CD11b+CD14+HLA+DRlow/–CD15–) and PMN-MDSCs (CD11b+CD14–CD15+/CD66b+). Functionally, MDSCs inhibit T cells via L-arginine depletion, nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species, and by upregulating immune checkpoints such as PD-L1 [11]. The clinical link between MDSC abundance and disease progression was established and it demonstrated that circulating MDSC levels correlate with advancing stage in PTC. This work suggested a role for MDSCs in systemic immune evasion [12]. In a recent pivotal study [13], authors demonstrated that the BRAF^V600E oncogene directly drives MDSC recruitment by reactivating the transcriptional regulator TBX3, which in turn upregulates CXCR2 ligands via TLR2-NF-κB signaling. This finding is particularly significant as it provides a direct link between a genetic driver and the creation of an immunosuppressive niche, offering a therapeutic rationale for CXCR2 blockade to restore MAPK inhibitors’ sensitivity. However, most evidence derives from mouse xenografts, which may not reflect the full complexity of the human tumor microenvironment. Also, the conclusion has been driven by BRAF^V600E papillary thyroid carcinoma, and it remains uncertain how well this axis applies to RAS-driven follicular cancers, RET-rearranged PTCs, or anaplastic transformation. In addition, patient validation cohorts were limited, underscoring the need for larger, subtype-specific clinical studies.

In ATC, the immunosuppressive landscape is even more profound. An earlier study suggested an increase in immunosuppressive myeloid cells, though their use of the crude marker CD11b+CD33+ limits the specificity of this conclusion for the present day MDSC definitions [14]. Nevertheless, ATC cells induce neutrophils to undergo NETosis, releasing mitochondrial DNA traps that further fuel progression and likely intertwine with PMN-MDSC pathways [15]. Clinically, immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have shown activity in subsets of ATC and are being integrated with targeted therapy; for example, a 2024 non-randomized trial showed improved overall survival by adding atezolizumab to a molecularly guided regimen in newly diagnosed ATC [16]. However, as in preclinical models in ATC, combining BRAF inhibition with anti–PD-1/PD-L1 improves survival and intratumoral immunity, but resistance eventually re-emerges with a re-dominant immunosuppressive myeloid milieu. This recurrence underscores a fundamental limitation i.e. the need to modulate MDSCs/TAMs alongside ICIs and MAPK blockade [17]. This realization has spurred investigation into myeloid-focused strategies. Therefore, a proposed framework would be to build a combination therapy that simultaneously blocks tumor-intrinsic signaling (e.g., BRAF/MEKi), relieve myeloid suppression (e.g., via CXCR2 or DHODH inhibition), and activate T-cells (with ICIs). While preclinical data (including reference [13]) provides a strong biologic rationale for this approach, it has some strong translational hurdles. Firstly, the CXCR2 blockade primarily targets PMN-MDSCs but may not address suppression mediated by M-MDSCs or other key players. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), which often outnumber MDSCs, can create redundant immunosuppressive mechanisms through M2 polarization. Furthermore, Tregs can maintain suppression independently through TGF-β and IL-10 and may even expand if MDSCs are depleted. Secondly, the toxicity profile of such a combination could be prohibitive. BRAF/MEKi cause significant fatigue, rash, and hepatotoxicity; adding CXCR2 inhibition risks neutropenia and impaired antimicrobial defense; and ICIs introduce immune-related adverse events. Therefore, axis of oncogene-driven myeloid recruitment represents a genuine therapeutic vulnerability; but the cumulative side-effect burden is a major concern for clinical deployment. Future efforts must prioritize developing biomarkers to identify patients with myeloid dominant TIMEs who are most likely to benefit and prioritize sequential or intermittent dosing schedules to mitigate overlapping toxicities.

Immune Checkpoint Pathways Beyond PD-1/PDL-1 and CTLA4

Immune checkpoint pathways play a pivotal role in shaping the thyroid cancer TIME by promoting immune evasion through T cell exhaustion, apoptosis and consequent immunosuppression. Emerging checkpoints such as LAG-3 and TIM-3 also exacerbate T cell exhaustion and immune evasion. LAG-3 (CD223) is an inhibitory co-receptor expressed on various immune cells, including activated T cells (CD4+, CD8+, and regulatory T cells/Tregs), as well as on natural killer (NK) cells, activated B cells, and plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) [18]. Unlike PD-1 and CTLA-4, LAG-3 is generally not expressed on naive T cells but is induced upon T cell activation [18,19]. Sustained expression of LAG-3, often alongside other inhibitory receptors like PD-1 and TIM-3, significantly contributes to T cell dysfunction and exhaustion, particularly in contexts of chronic antigen stimulation, such as in the case of immunogenic cancer. Upregulation of LAG-3 may serve as a compensatory mechanism of resistance to PD-1 inhibitor monotherapy. The clinical relevance of this synergy is highlighted by trials that led to the FDA approval of combination therapy involving relatlimab (a LAG-3 inhibitor) and nivolumab (a PD-1 inhibitor) for advanced melanoma. This makes LAG-3 a critical emerging target in thyroid cancer immunotherapy, particularly for patients who may be refractory to single-agent immune checkpoint inhibition. T-cell Immunoglobulin and Mucin-domain Containing-3 (TIM-3) is another important immune checkpoint protein expressed on various immune cells, including Th1, Th17, monocytes, DCs, and macrophages [19]. TIM-3 plays a key role in immunoregulation and is implicated in CD8+ T-cell depletion. Similar to LAG-3, TIM-3 is also associated with T cell exhaustion, contributing to the dysfunctional state of anti-tumor T cells. A critical discovery regarding TIM-3 is its direct role in shaping the immunosuppressive TIME through its influence on macrophage polarization. TIM-3 expression is upregulated in monocytes cultured with ATC cell-derived conditioned media, and importantly, blockade of TIM-3 significantly reverses this M2 polarization [20]. Furthermore, TIM-3 directly facilitates the migration and invasion of thyroid cancer cells via activation of the ERK1/2 signaling pathway, thereby establishing its significant contribution to shaping an immunosuppressive and pro-tumorigenic milieu [21].

In parallel, immune-cell dysfunction extends beyond T cells. B cells exhibit dual roles, either suppressing immunity via IL-10/TGF-β or enhancing it through antigen presentation and development of tertiary lymphoid structures. NK cells face exhaustion from inhibitory receptors like PD-1 and TIM-3. Although immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have shown marked success in ATC particularly dual blockade (e.g., anti-PD1-nivolumab + anti-CTLA4-ipilimumab) and combinations with targeted therapies (e.g., antiPD-L1- atezolizumab + vemurafenib / cobimetinib), their efficacy is often limited by primary and acquired resistance mechanisms, including low tumor immunogenicity, defective antigen presentation, poor CD8+ T cell infiltration, irreversible T cell exhaustion, and compensatory checkpoint upregulation (e.g., LAG-3, TIM-3), alongside TIME changes like increased myeloid-derived suppressor cells. A promising futuristic approach in thyroid cancer immunotherapy involves targeting intracellular checkpoint molecules-like, within natural killer (NK) cells, FBP-1, EZH2, CIS, TIPE2, and HIF-1α, which drive NK cell exhaustion [22]. Although limited by vector delivery systems, by directly restoring intrinsic NK cell function, this strategy could overcome key limitations of current immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and pave the way for next-generation immunotherapies aimed at reactivating immune responses in thyroid cancer and beyond.

Current Challenges

Thyroid cancer care faces pivotal challenges in both diagnosis and treatment. The widespread use of high-resolution imaging has led to the detection of thyroid nodules, with many representing small papillary thyroid carcinomas that may never progress to clinically meaningful disease. This has led to overtreatment and patients are subjected to unnecessary surgical interventions and associated psychological morbidity [23]. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA), while widely used, yields indeterminate results in up to 30% of nodules, often prompting invasive surgery even when most prove benign [24]. Molecular testing and mutation panels (e.g., BRAF, RET, TERT) have improved risk stratification, but their high cost, variable availability, and different detections thresholds, incur limitations on their application. Artificial intelligence-based tools for ultrasound and cytology interpretation are showing early promise but aren’t yet available for routine clinical use [25]. On the treatment side, radioactive iodine (RAI)-refractory disease remains a major barrier, with resistance often linked to loss of sodium-iodide symporter (NIS) expression and immunosuppressive microenvironmental cues. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors have revolutionized treatment for advanced disease, yet their use is associated with substantial toxicity, modest overall survival gains, and the eventual emergence of resistance. Although recent investigations suggest potential synergy with immune checkpoint inhibitors through microenvironment modulation, resistance eventually re-emerges with a re-dominant immunosuppressive myeloid milieu [26]. Epidemiologically obesity and endocrine-disrupting chemicals are risk factors but need further experimental validation [27]. Despite recent updates to clinical guidelines reflecting efforts to provide evidence-based recommendations [28], thyroid cancer TIME interventions remain completely under the clinical radar.

Conclusion

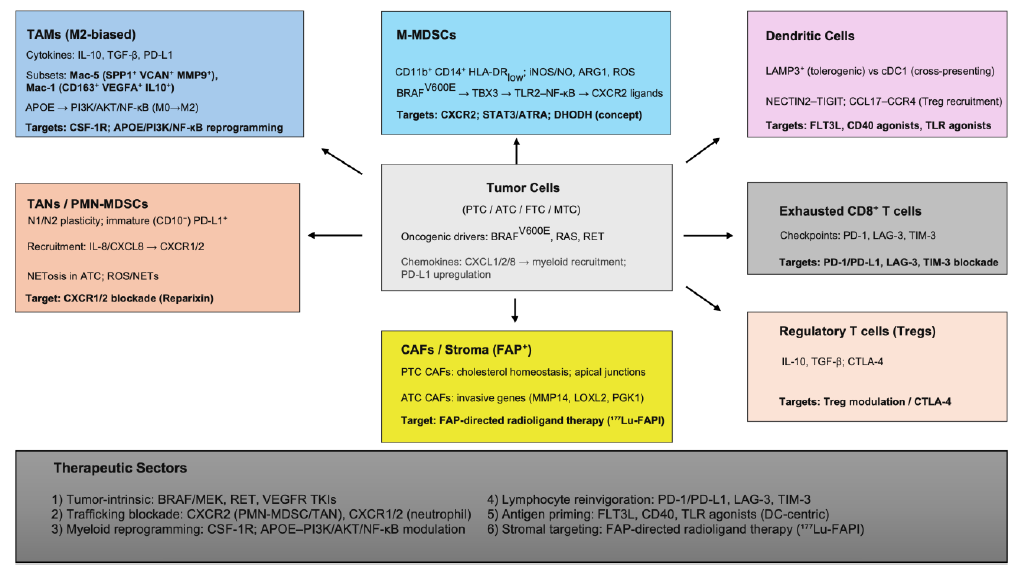

Thyroid cancer tumor immune microenvironment (TIME) is a network of cells, pathways and signaling (Figure 1). Single-cell/spatial transcriptomic profiling has uncovered many novel subsets and dynamic cell states across the TIME that challenged earlier categorization into descriptive pro tumor / anti-tumor cells. Therefore, conventional therapies that focused on highly prevalent mutations or a dominant pathway targeting few cellular elements need to shift towards integrating spatial, temporal, molecular, and functional immune dynamics simultaneously. TAMs and TANs warrant special attention as their metabolic and functional plasticity offers an attractive therapeutic target and pairing them with newer ICI targets like LAG-3 and TIM-3 may offer better outcomes. Future therapeutic strategies should focus on modulating specific myeloid subsets such as Mac-5, Mac-1, and PD-L1+ immature neutrophils through agents like CSF-1R inhibitors, PI3K/NF-κB modulators, or NET-disrupting drugs. Revisiting DC based strategies like expanding cross-presenting cDC1s, or restoring antigen presentation by depleting or reprogramming tolerogenic LAMP3+ dendritic cells could overcome resistance in low-immunogenicity subtypes. The Holy Grail, however, may lay on back-programing exhaustion to reset sensitivity to any possible form of immune stimulation/reconstitution.

Figure 1. Thyroid cancer immune microenvironment: immune cell associations and therapeutic targets.

References

2. Han PZ, Ye WD, Yu PC, Tan LC, Shi X, Chen XF, et al. A distinct tumor microenvironment makes anaplastic thyroid cancer more lethal but immunotherapy sensitive than papillary thyroid cancer. JCI Insight. 2024 Mar 7;9(8):e173712.

3. Huo R, Zhao R, Li Z, Li M, Bin Y, Wang D, et al. APOE expression in papillary thyroid carcinoma: Influencing tumor progression and macrophage polarization. Immunobiology. 2024 Sep;229(5):152821.

4. Liao T, Zeng Y, Xu W, Shi X, Shen C, Du Y, et al. A spatially resolved transcriptome landscape during thyroid cancer progression. Cell Rep Med. 2025 Apr 15;6(4):102043.

5. Strack E, Rolfe PA, Fink AF, Bankov K, Schmid T, Solbach C, et al. Identification of tumor-associated macrophage subsets that are associated with breast cancer prognosis. Clin Transl Med. 2020 Dec;10(8):e239.

6. Modak M, Mattes AK, Reiss D, Skronska-Wasek W, Langlois R, Sabarth N, et al. CD206+ tumor-associated macrophages cross-present tumor antigen and drive antitumor immunity. JCI Insight. 2022 Jun 8;7(11):e155022.

7. Lee SE, Koo BS, Sun P, Yi S, Choi NR, Yoon J, et al. Neutrophil diversity is associated with T-cell immunity and clinical relevance in patients with thyroid cancer. Cell Death Discov. 2024 May 8;10(1):222.

8. Liotti F, De Pizzol M, Allegretti M, Prevete N, Melillo RM. Multiple anti-tumor effects of Reparixin on thyroid cancer. Oncotarget. 2017 May 30;8(22):35946–61.

9. Wang Z, Ji X, Zhang Y, Yang F, Su H, Zhang H, et al. Interactions between LAMP3+ dendritic cells and T-cell subpopulations promote immune evasion in papillary thyroid carcinoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2024 May 30;12(5):e008983.

10. Fu H, Huang J, Zhao T, Wang H, Chen Y, Xu W, et al. Fibroblast Activation Protein-Targeted Radioligand Therapy with 177Lu-EB-FAPI for Metastatic Radioiodine-Refractory Thyroid Cancer: First-in-Human, Dose-Escalation Study. Clin Cancer Res. 2023 Dec 1;29(23):4740–50.

11. Bronte V, Brandau S, Chen S-H, Colombo MP, Frey AB, Greten TF, et al. Recommendations for myeloid-derived suppressor cell nomenclature and characterization standards. Nat Commun. 2016 Jul 6;7:12150.

12. Angell TE, Lechner MG, Smith AM, Martin SE, Groshen SG, Maceri DR, et al. Circulating Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Predict Differentiated Thyroid Cancer Diagnosis and Extent. Thyroid. 2016 Mar;26(3):381–9.

13. Zhang P, Guan H, Yuan S, Cheng H, Zheng J, Zhang Z, et al. Targeting myeloid derived suppressor cells reverts immune suppression and sensitizes BRAF-mutant papillary thyroid cancer to MAPK inhibitors. Nat Commun. 2022 Mar 24;13(1):1588.

14. Suzuki S, Shibata M, Gonda K, Kanke Y, Ashizawa M, Ujiie D, et al. Immunosuppression involving increased myeloid-derived suppressor cell levels, systemic inflammation and hypoalbuminemia are present in patients with anaplastic thyroid cancer. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013 Nov;1(6):959–64.

15. Cristinziano L, Modestino L, Loffredo S, Varricchi G, Braile M, Ferrara AL, et al. Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer Cells Induce the Release of Mitochondrial Extracellular DNA Traps by Viable Neutrophils. J Immunol. 2020 Mar 1;204(5):1362–72.

16. Cabanillas ME, Dadu R, Ferrarotto R, Gule-Monroe M, Liu S, Fellman B, et al. Rare Tumor Initiative Team. Anti–Programmed Death Ligand 1 Plus Targeted Therapy in Anaplastic Thyroid Carcinoma: A Nonrandomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2024 Oct 24;10(12):1672–80.

17. Gunda V, Gigliotti B, Ndishabandi D, Ashry T, McCarthy M, Zhou Z, et al. Combinations of BRAF inhibitor and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody improve survival and tumour immunity in an immunocompetent model of orthotopic murine anaplastic thyroid cancer. Br J Cancer. 2018 Nov;119(10):1223–32.

18. Liu X, Xi X, Xu S, Chu H, Hu P, Li D, et al. Targeting T cell exhaustion: emerging strategies in non-small cell lung cancer. Front Immunol. 2024 Dec 12;15:1507501.

19. Cianciotti BC, Magnani ZI, Ugolini A, Camisa B, Merelli I, Vavassori V, et al. TIM-3, LAG-3, or 2B4 gene disruptions increase the anti-tumor response of engineered T cells. Front Immunol. 2024 Feb 29;15:1315283.

20. Stempin CC, Geysels RC, Park S, Palacios LM, Volpini X, Motran CC, et al. Secreted Factors by Anaplastic Thyroid Cancer Cells Induce Tumor-Promoting M2-like Macrophage Polarization through a TIM3-Dependent Mechanism. Cancers (Basel). 2021 Sep 26;13(19):4821.

21. Jin X, Yin Z, Li X, Guo H, Wang B, Zhang S, et al. TIM3 activates the ERK1/2 pathway to promote invasion and migration of thyroid tumors. PLoS One. 2024 Apr 3;19(4):e0297695.

22. Huang Y, Tian Z, Bi J. Intracellular checkpoints for NK cell cancer immunotherapy. Front Med. 2024 Oct;18(5):763–77.

23. Dal Maso L, Vaccarella S. Trends in thyroid cancer incidence and overdiagnosis in the USA. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2025 Mar;13(3):167–9.

24. Vignali P, Macerola E, Poma AM, Sparavelli R, Basolo F. Indeterminate Thyroid Nodules: From Cytology to Molecular Testing. Diagnostics (Basel). 2023 Sep 20;13(18):3008.

25. Shen P, Yang Z, Sun J, Wang Y, Qiu C, Wang Y, et al. Explainable multimodal deep learning for predicting thyroid cancer lateral lymph node metastasis using ultrasound imaging. Nat Commun. 2025 Aug 1;16(1):7052.

26. Puliafito I, Esposito F, Prestifilippo A, Marchisotta S, Sciacca D, Vitale MP, et al. Target Therapy in Thyroid Cancer: Current Challenge in Clinical Use of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors and Management of Side Effects. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022 Jul 8;13:860671.

27. Kitahara CM, Schneider AB. Epidemiology of Thyroid Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2022 Jul 1;31(7):1284–97.

28. Ringel MD, Sosa JA, Baloch Z, Bischoff L, Bloom G, Brent GA, et al. 2025 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines for Adult Patients with Differentiated Thyroid Cancer. Thyroid. 2025 Aug;35(8):841–985.