Abstract

Our studies on the effects of mild hyperthermia (≤ 42°C) on prometaphase-arrested and interphase HeLa cells are reviewed. Mild heat treatment rapidly induces apoptosis in H-HeLa cells that have been arrested in prometaphase with spindle poisons. This is shown by the appearance of morphological changes characteristic of apoptosis, the activation of Caspase 3, and the fact that the changes are blocked by caspase inhibitors such as zVAD-fmk. The same treatment does not cause apoptosis in interphase cells, or in prometaphase-arrested cells of other HeLa strains such as HeLa S3, MKF, and WML. However, prometaphase-arrested cultures of those other HeLa strains can be made sensitive to mild heat treatment by simultaneous exposure to compounds such as navitoclax (ABT-263) which inhibit Bcl-2 family anti-apoptotic proteins. Interphase cells can be made sensitive to 42°C treatment by combining ABT-263 or ABT-199 with S63845, a potent and selective inhibitor of MCL-1. These studies suggest that it might be possible to find a treatment for tumors that combines systemic drug treatment with localized hyperthermia. Clues to how that might be achieved are discussed.

Keywords

ABT-263, Apoptosis, Bcl-2, HeLa cells, Hyperthermia, Navitoclax, Prometaphase arrest, S63845

Introduction

Apoptosis is a process of programmed cell death which the body uses to get rid of unneeded or unwanted cells without causing inflammation or autoimmunity [1-3]. It occurs, for example, during development, in the elimination of infected cells, and in surveillance and destruction of cells that may be cancerous. Apoptosis can be the result of either an extrinsic pathway or an intrinsic pathway [4-6]. In the extrinsic pathway, cell death is initiated by the binding of external signaling molecules to cell-surface “death receptors”. The intrinsic pathway, on the other hand, results from internal stress in the cell and is signaled by the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria. In both pathways, cell death results from the activation of proteolytic enzymes called caspases, which are responsible for morphological changes in the cell, degradation of proteins and DNA, and ultimately disintegration of the cell [6-10].

Radiation therapy and chemotherapy induce apoptosis via the intrinsic pathway during cancer treatment [11-15]. Hyperthermia (heat treatment) can also induce apoptosis and has been used to treat cancer, sometimes in combination with chemotherapy or radiation [16-24].

More than 20 years ago, we made observations suggesting that a new approach to cancer treatment might be possible which combines systemic or local drug treatment with localized hyperthermia. Our initial discovery was that mild hyperthermia induces apoptosis in prometaphase-arrested H-HeLa, a particular strain of HeLa cells [25], and this led to the idea of treating cancer with a combination of spindle poisons and hyperthermia. We subsequently found that hyperthermia will also induce apoptosis in prometaphase-arrested cells of other HeLa strains if those cells are simultaneously treated with certain inhibitors of Bcl-2 family anti-apoptotic proteins [26].

This paper reviews the progress we have made. The approach under investigation is far from ready to be used therapeutically. However, the work completed so far gives clues as to how the research may be carried out further, potentially leading to a new cancer therapy.

Origins of This Research in Studies of Exit from Mitosis

The work reviewed here was in a sense a byproduct of research begun in the 1990s on exit from mitosis in H-HeLa cells, a strain provided to us by Prof. Roland Rueckert. (H-HeLa was used in Rueckert’s lab to study poliovirus and rhinoviruses because it is susceptible to infection by those agents [27]. However, we have no evidence that this property is relevant to our studies of apoptosis.)

During studies on mitotic histone H1 dephosphorylation, we observed that treatment of prometaphase-arrested H-HeLa cells with the protein kinase inhibitor staurosporine caused histones to be dephosphorylated, chromosomes to decondense, and interphase nuclei to reassemble [28]. Since the onset of mitosis is signaled by activation of the protein kinase Cdk1-cyclin B [29] and staurosporine inhibits Cdk1 [30], we suggested that inactivation of Cdk1-cyclin B may be the trigger for the M- to G1-phase transition [28].

We first tested this hypothesis using mouse FT210 cells, in which Cdk1 is temperature sensitive [31]. This allowed for specific inactivation of Cdk1, in contrast to staurosporine which inhibits multiple protein kinases [30]. FT210 cells were grown at their permissive temperature (32°C), arrested with nocodazole, and then shifted to higher temperature (typically 41.5°C). This caused the cells to exit mitosis and enter G1-phase as demonstrated by reassembly of interphase nuclei, dephosphorylation of histones, and the cells’ ability to complete another cell cycle, passing through S-phase and arresting in mitosis again [32]. This result and later work with budding yeast [33] helped to confirm that Cdk1 inactivation is sufficient to trigger the M- to G1-phase transition.

One concern in carrying out the FT210 experiments was that perhaps exit from mitosis was due to some other effect of the heat treatment, not inactivation of Cdk1. If so, perhaps heat treatment would induce mitotic exit in any prometaphase-arrested cells. To test this possibility, H-HeLa cells were arrested in prometaphase of mitosis and shifted to 41.5°C. However, these cells did not make the transition to G1-phase. Instead, they exhibited morphological changes suggestive of apoptosis.

Induction of Apoptosis in Prometaphase-Arrested H-HeLa Cells by Mild Hyperthermia

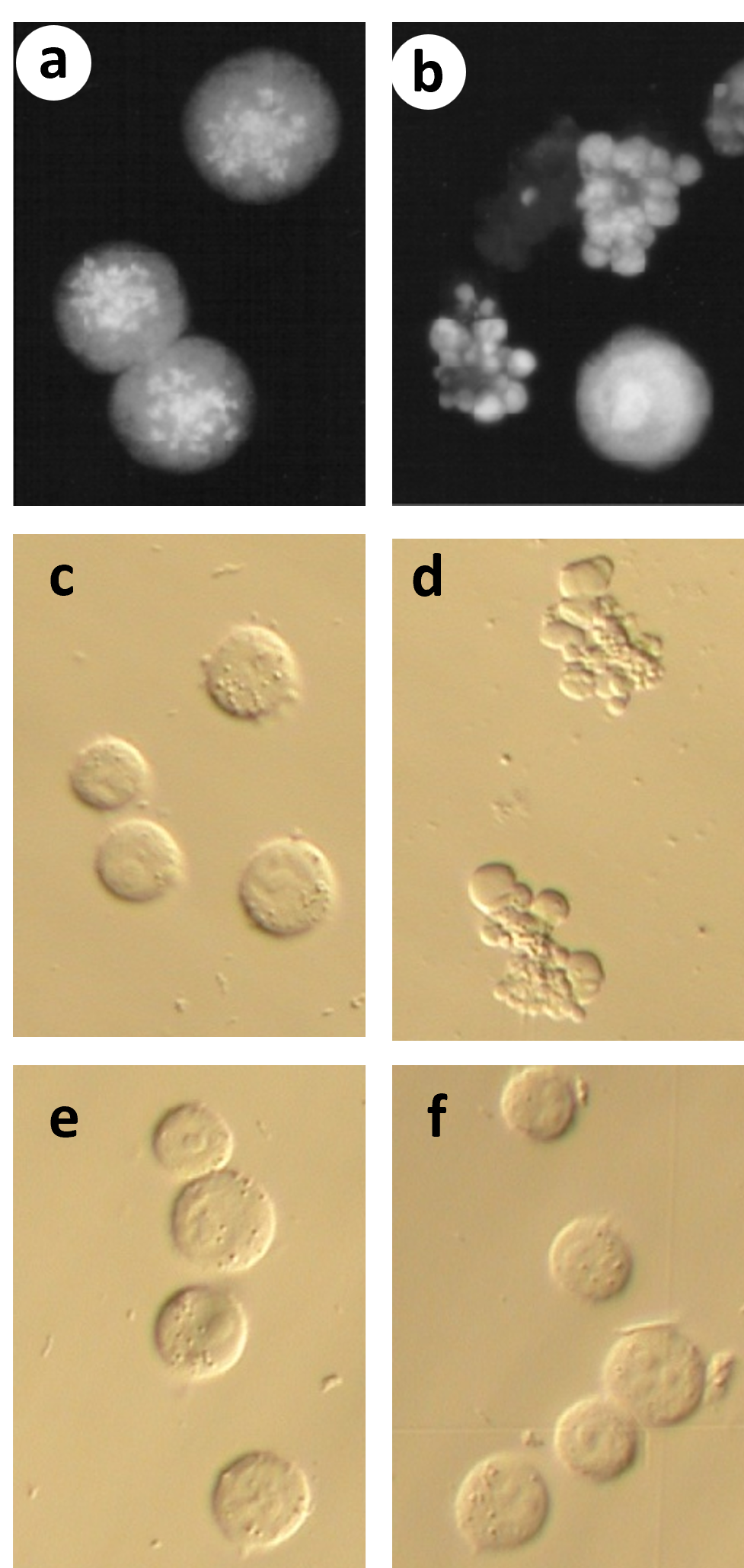

Several experiments demonstrated that indeed, mild hyperthermia induces apoptosis in prometaphase-arrested but not interphase H-HeLa cells [25]. (Figure 1) shows that prometaphase-arrested H-HeLa cells treated at 41.5°C undergo morphological changes typical of apoptosis, including condensation and fragmentation of the chromatin (Figure 1b) and blebbing of the plasma membrane (Figures 1b and 1d). A nucleated cell in the lower right of (Figure 1b) suggests that heat treatment does not affect interphase cells, and this is confirmed by the lack of blebbing following heat treatment of an interphase culture in (Figure 1f) [25]. (Evidence that this blebbing is due to apoptosis will be discussed below.)

Figure 1. Heat treatment causes morphological changes characteristic of apoptosis in prometaphase-arrested but not interphase H-HeLa cells. (a-b) Cells were arrested in prometaphase with nocodazole (mitotic index 85%) and either left at 37.0°C or shifted to 41.5°C. Samples were treated hypotonically, fixed with methanol:acetic acid, stained with Hoechst 33342, and viewed by fluorescence microscopy. (a) Cells left at 37.0°C for 3 hr are still in prometaphase arrest; (b) Most cells treated at 41.5°C for 3 hr show blebbing of the plasma membrane, and nuclear condensation and fragmentation. Interphase cells are seen (e.g., bottom right), but no mitotic cells are observed. (c-f) Cells were viewed by Hoffman modulation contrast, unfixed. (c) Prometaphase-arrested cells left at 37°C; (d) Prometaphase arrested cells treated 2 hrs at 41.5°C. Note the extensive blebbing of the plasma membrane; (e) Interphase cells left at 37°C; (d) Interphase cells treated 2 hrs at 41.5°C. (Figure adapted from Paulson et al. [25]).

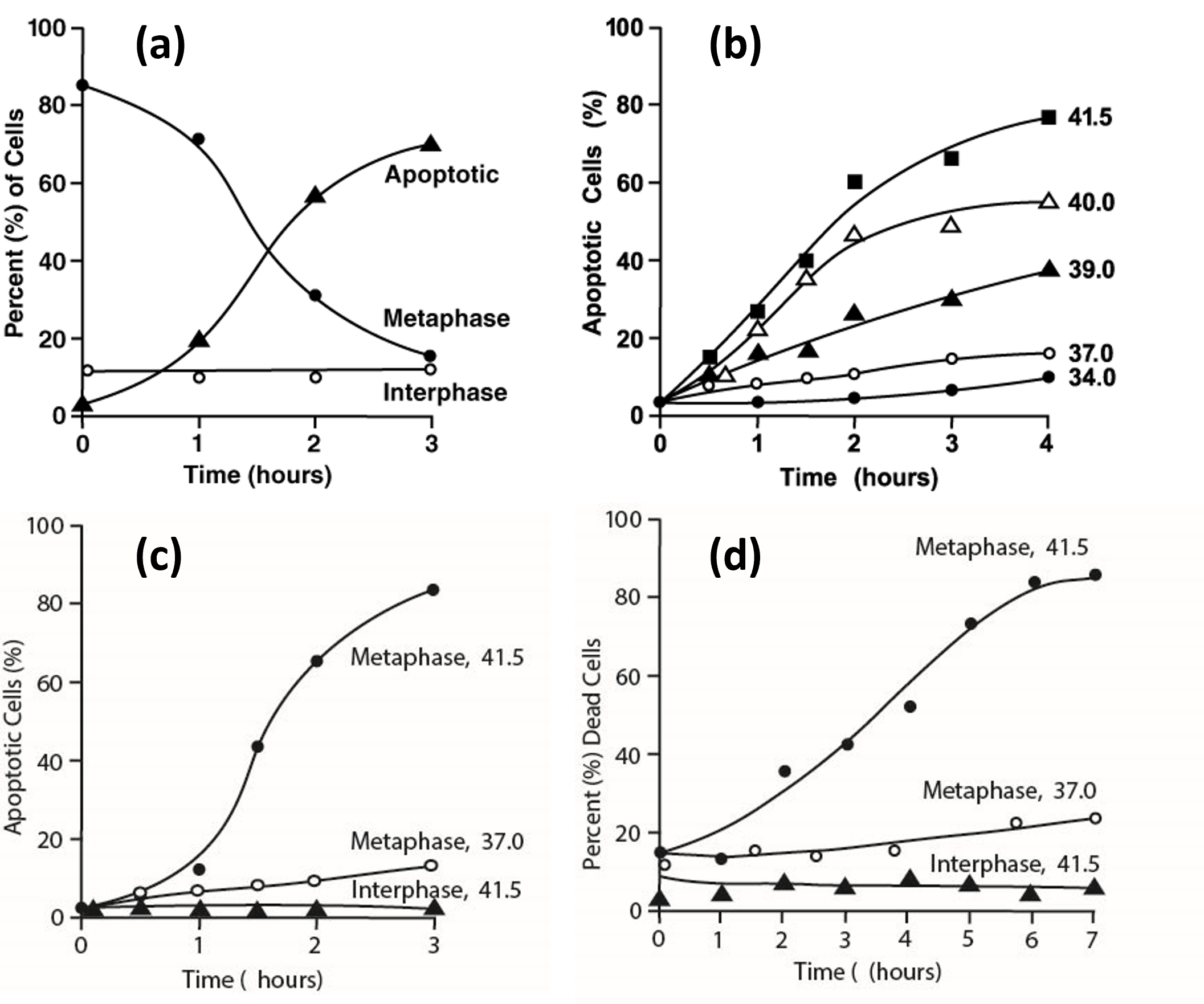

Further evidence that mild hyperthermia affects prometaphase-arrested but not interphase H-HeLa cells is shown in (Figure 2). (Figure 2a) shows the results of treating a prometaphase-arrested culture (mitotic index 86%) at 41.4°C. With time, the percentage of apoptotic cells increases as the percentage of prometaphase cells decreases, but the percentage of nuclei-containing (interphase) cells remains constant at about 14% [25]. (Figure 2c) shows the percentages of apoptotic cells as a function of time during 41.5°C treatment of prometaphase-arrested and interphase (unsynchronized) cultures. Apoptosis occurs with the prometaphase-arrested cells but not with the interphase cells. (Figure 2d) shows cell viability in samples from the same cultures, determined by permeability to propidium iodide. Prometaphase-arrested cells undergo cell death at 41.5°C, though more slowly than they undergo blebbing (Figure 2c), whereas interphase cells remain viable at 41.5°C [25].

Figure 2. Effects of heat treatment on prometaphase-arrested and interphase H-HeLa. (a) Time course of induction of apoptosis in a H-HeLa culture arrested in prometaphase at 37°C (mitotic index 86%) and then treated at 41.4°C. At various times, samples were prepared for fluorescence microscopy as in Figure 1a and 1b and the percentages of interphase (?—?), prometaphase (???), and apoptotic cells (???) were determined. (b) Temperature dependence of the rate of induction of apoptosis. H-HeLa arrested in prometaphase (mitotic index 91%) were treated at 34.0 (???), 37.0 (???), 39.0 (???), 40.0 (???) and 41.5°C (???). (c), (d) Comparison of prometaphase-arrested H-HeLa treated at 41.5°C or 37.0°C and interphase H-HeLa treated at 41.5°C. (c) Percentage of apoptotic cells (as in Figure 2a) as a function of time; (d) Percentage of dead cells, assayed by propidium iodide permeability. (Adapted from Paulson et al. [25]).

(Figure 2b) shows how apoptosis is induced in prometaphase-arrested H-HeLa at different temperatures. It occurs more slowly and to a lesser extent at 39°C and 40°C than at 41.5°C.

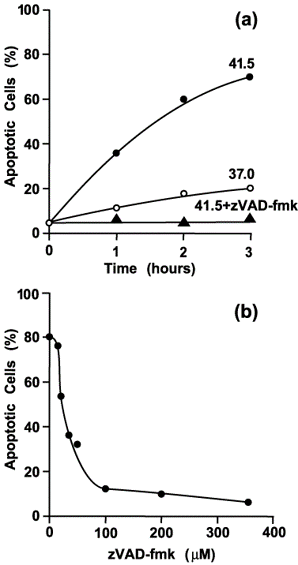

(Figure 3a) confirms that the morphological changes described above (e.g., Figure 1b) are indeed signs of apoptosis, because they are prevented by the presence of 350 μM zVAD-fmk, a caspase inhibitor [34]. (Figure 3b) shows the extent of apoptosis after 3 hours at 41.5°C as a function of zVAD-fmk concentration.

Figure 3. Morphological changes due to heat treatment of prometaphase-arrested H-HeLa cells are blocked by the caspase inhibitor zVAD-fmk. (a) Time course for cells that were arrested at 37.0°C (mitotic index 90%) and then either left at 37.0°C (???), shifted to 41.5°C (???), or shifted to 41.5°C in the presence of 350 μM zVAD-fmk (???). (b) Percentage of cells with morphological changes characteristic of apoptosis as a function of the zVAD-fmk concentration. Culture aliquots were treated for 3 hours at 41.5°C. (Adapted from Paulson et al. [25].)

Additional experiments also confirm that heat-treated prometaphase-arrested H-HeLa cells undergo apoptosis. First, one can observe the cleavage and activation of procaspase 3 using gel electrophoresis and western blotting (Figure 6 in [25]). Second, activated caspase 3 can be detected inside the cells using the fluorescent probe FAM-VAD-fmk (Figure 7 in [25]).

Note that in (Figures 2b and 3a), nocodazole-arrested H-HeLa cells undergo apoptosis to some extent even at 37°C. This suggests that when treating a HeLa culture with a spindle poison for many hours at 37°C, for example in preparation for the isolation of metaphase chromosomes, it may be useful to treat the culture at the same time with zVAD-fmk.

Effects of Heat and Drug Treatments on Other Prometaphase-Arrested HeLa Strains

As described above, when H-HeLa cells are arrested in prometaphase and then exposed to mild hyperthermia, they rapidly undergo apoptosis [25]. The same results are obtained whether the cells are arrested with nocodazole, paclitaxel, or colchicine. Since spindle poisons and hyperthermia have been used, separately, to treat cancer, these results suggested that combining systemic treatment with spindle poisons and localized hyperthermia might be developed as an effective treatment for tumors.

However, we soon found that heat treatment of prometaphase-arrested cells does not induce apoptosis in other HeLa strains, including HeLa S3, MKF and WML. These results raised major questions. Why do other HeLa strains behave differently from H-HeLa? Why are prometaphase-arrested H-HeLa susceptible to heat while interphase H-HeLa are not?

One possibly relevant difference between mitotic and interphase cells is the downregulation of anti-apoptotic proteins during mitosis, reported by Han et al. [35]. As a first step toward exploring the above questions, therefore, we examined the effects of drugs which inhibit anti-apoptotic proteins.

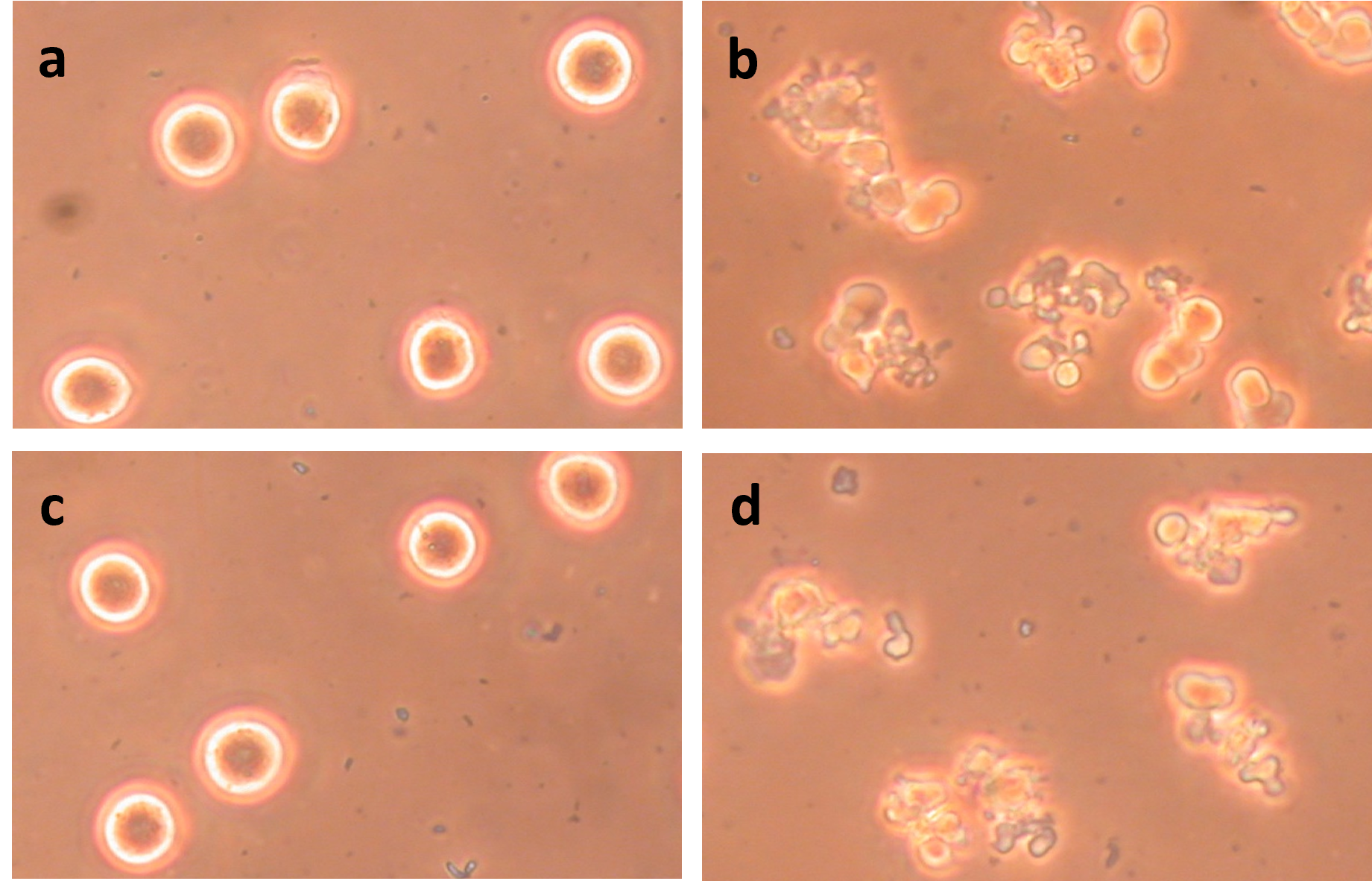

(Figure 4) shows the effects of treating prometaphase-arrested HeLa S3 at 42°C with ABT-263 (navitoclax), an inhibitor of Bcl-2 and other anti-apoptotic proteins [36]. The cells were arrested either with nocodazole (Figures 4a and 4b) or paclitaxel (Figures 4c and 4d). All these cells were incubated at 42°C for 50 minutes, but those on the right (Figures 4b and 4d) were also treated with 5 μM ABT-263. Clearly, HeLa S3 can be induced to undergo extensive plasma membrane blebbing by treatment at 42°C if they are also treated with ABT-263

Figure 4. Induction of apoptosis in prometaphase-arrested HeLa S3 by treatment with heat and ABT-263. All cultures were treated for 50 min at 42°C. (a) HeLa S3 arrested in prometaphase with 0.2 μg/mL nocodazole; (b) Same as (a) but heat-treated in the presence of 5 μM ABT-263; (c) HeLa S3 arrested in prometaphase with 0.25 μM paclitaxel; (d) Same as (c) but heat-treated in the presence of 5 μM ABT-263. These micrographs and those in Figures 5, 6, and 8 were taken using phase contrast.

Figure 5 shows that both heat treatment and ABT-263 are required to induce blebbing in prometaphase-arrested HeLa S3 and that the blebbing is due to apoptosis. Plasma membrane blebbing is not seen following treatment at 34°C with ABT-263 (Figure 5b) or treatment at 42°C without ABT-263 (Figure 5c). Both ABT-263 and 42°C are necessary to induce apoptosis (Figure 5d). The membrane blebbing is blocked by 100 μM DEVD-cho (Figure 5e) and by 200 μM zVAD-fmk (Figure 5f), confirming that the cells in Figure 5d are undergoing apoptosis. Western blotting of caspase 3 provides further evidence that apoptosis is occurring (Figure 6 in [26]).

Figure 5. Induction of apoptosis in prometaphase-arrested HeLa S3 requires both ABT-263 and heat and is blocked by caspase inhibitors DEVD-cho and zVAD-fmk. (a) Untreated cells; (b) Cells treated for 60 min at 34°C with 5 μM ABT-263; (c) Cells treated for 60 min at 42°C without ABT-263; (d) Cells treated for 60 min at 42°C with 5 μM ABT-263; (e) Cells treated for 60 min at 42°C with 5 μM ABT-263 and 100 μM DEVD-cho; (f) Cells treated for 60 min at 42°C with 5 μM ABT-263 and 200 μM zVAD-fmk.

Figure 6. Treatment with 5 μM ABT-263 at 42°C does not induce apoptosis in HeLa S3 interphase cells. (a) Prometaphase-arrested cells before treatment; (b) Prometaphase-arrested cells treated for 40 min with 5 μM ABT-263 at 42°C; (c) Interphase cells before treatment; (d) Interphase cells treated for 40 min with 5 μM ABT-263 at 34°C; (e) Interphase cells treated for 40 min at 42°C without ABT-263; (f) Interphase cells treated for 40 min with 5 μM ABT-263 at 42°C.

Interphase HeLa S3 cells do not undergo apoptosis when treated at 42°C (Figure 6e), as was shown for H-HeLa above. Nor do they undergo apoptosis when treated at 42°C with ABT-263 (Figures 6f and Figure 7a).

Figure 7. Apoptosis induced in HeLa S3 and WML. (a) Induction of apoptosis in prometaphase-arrested (???) but not interphase (???) HeLa S3 cells by treatment with 5 μM ABT-263 at 42°C. (b) Induction of apoptosis in prometaphase arrested HeLa WML cells by treatment at 42°C with 5 μM ABT-263 (???), but not by treatment at 42°C without ABT-263 (???), not by treatment at 42°C with 5 μM ABT-263 and 200 μM zVAD-fmk (??), and not by treatment at 42°C with 110 μM obatoclax (???).

The micrographs presented in Figures 4-6, all show HeLa S3 cells, but essentially the same results have been obtained with other strains such as HeLa WML. Figure 7b confirms that simple treatment of prometaphase-arrested HeLa WML at 42°C does not induce apoptosis, but treatment at 42°C with ABT-263 does. As expected, it is blocked by zVAD-fmk (Figures 7b and 8c).

It should be noted that in experiments like the ones in Figure 7, the extent of apoptosis was quantitated by counting blebbed and unblebbed cells in a hemacytometer. Culture aliquots to be counted were fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde. This had no effect on the results, but it preserved the cells’ morphology for 24 hours, and probably longer. This allowed more time for counting, which was especially valuable in experiments that generated many samples. Also note that in all graphs presented here (Figures 2, 3, 7, 9, 10a and 11) at least 200 cells were counted for each sample.

Figure 8. Effects of 42°C, ABT-263, and obatoclax on prometaphase-arrested HeLa WML cells. (a) Cells incubated 40 min at 42°C; (b) Cells incubated 40 min at 42°C with 5 μM ABT-263; (c) Cells incubated 40 min at 42°C with 5 μM ABT-263 and 200 μM zVAD-fmk; and (d) Cells incubated 40 min at 42°C with 110 μM obatoclax.

Two other observations concerning treatment with ABT-263 at 42°C are worth noting. First, induction of apoptosis in prometaphase-arrested cells is not blocked by calyculin A, an inhibitor of protein phosphatases PPase1 and PPase2A [37], showing that PPase 1 and PPase 2A are not needed for induction of apoptosis. Interestingly, calyculin A can by itself induce blebbing of the plasma membrane, but this is not due to apoptosis. The cells remain in prometaphase and retain their condensed mitotic chromosomes. The blebbing effect is apparently due to phosphorylation of intermediate filament proteins [38].

Second, we have found that treatment of G1-phase cells with calyculin A causes them to form prematurely condensed chromosomes (G1-PCCs) [39], so that they closely resemble prometaphase-arrested cells. However, when cells containing G1-PCCs are treated with ABT-263 at 42°C, they do not become apoptotic.

Besides ABT-263, we have examined the effects of other drugs that act on anti-apoptotic or pro-apoptotic proteins. One of these is obatoclax, a pan-Bcl-2 family inhibitor [40,41]. However, HeLa WML cells treated at 42°C with 110 μM obatoclax do not undergo blebbing (Figures 7b and 8d). The treatment does cause a change in the appearance of the cells (Figure 8d), but that change is not affected by the presence of zVAD-fmk.

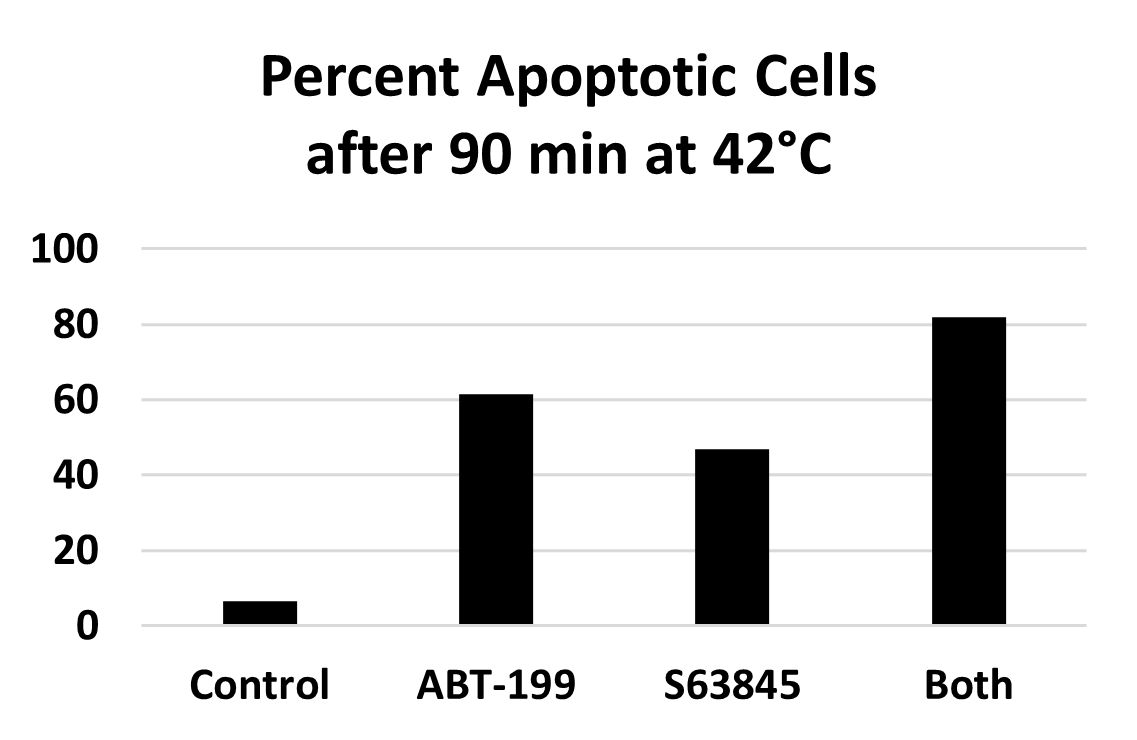

AB-199 (venetoclax) is another drug that binds to Bcl-2 and can trigger events that lead to apoptosis [42-45] and S63845 binds to the antiapoptotic protein Mcl1 [46,47]. These drugs also induce apoptosis when used to treat prometaphase-arrested HeLa S3 at 42°C, but they are less effective than ABT-263 at the same concentration. However, treatment of prometaphase-arrested HeLa S3 with both ABT-199 and S63845 is more effective than either one alone (Figure 9). Synergistic action of ABT-199 and S63845 has been reported previously by Li et al. [48].

Figure 9. Induction of apoptosis in prometaphase-arrested HeLa S3 by treatment at 42°C for 90 min with either 10 μM ABT-199, 10 μM S63845, or both.

We have also tested BAM7, a compound which activates the pro-apoptotic protein Bax [49]. However, it did not cause apoptosis in HeLa S3 cells at 42°C.

Moving on to Interphase Cells

The goal of this research is to find, if possible, a combination of systemic chemotherapy and localized hyperthermia that would be an effective treatment for cancerous tumors. Unfortunately, the results described above, in which apoptosis is induced in prometaphase-arrested cells, are unlikely to be very useful. Even though spindle poisons have been used in chemotherapy, it would be surprising if treatment with them caused more than a small fraction of the tumor cells to arrest in prometaphase.

What is needed is a treatment that makes interphase cells as sensitive to hyperthermia as prometaphase-arrested cells. What are the relevant features of mitotic cells? We do not yet know. But it may be possible to get clues by investigating differences among interphase cells, prometaphase-arrested cells, and cells with G1-PCCs. Perhaps there is a difference in survivin, which is tied up in the chromosome passenger complex during mitosis [50]. This could be explored using drugs such as YM-155 (sepantronium bromide) which blocks expression of survivin [51]. Alternatively, there may be inhibitors of Bcl-2 family proteins that are better than the ones we have tried (e.g., [52-55]). Another clue may be found in the phenomenon of transcriptional repression during mitosis [56,57].

The aim is to find a drug treatment which makes interphase cells behave like prometaphase-arrested cells. Ideally, such a treatment would have no negative effects on interphase cells at 37°C. We are far from such an ideal, but preliminary results with interphase HeLa S3 cells suggest that it might be realizable.

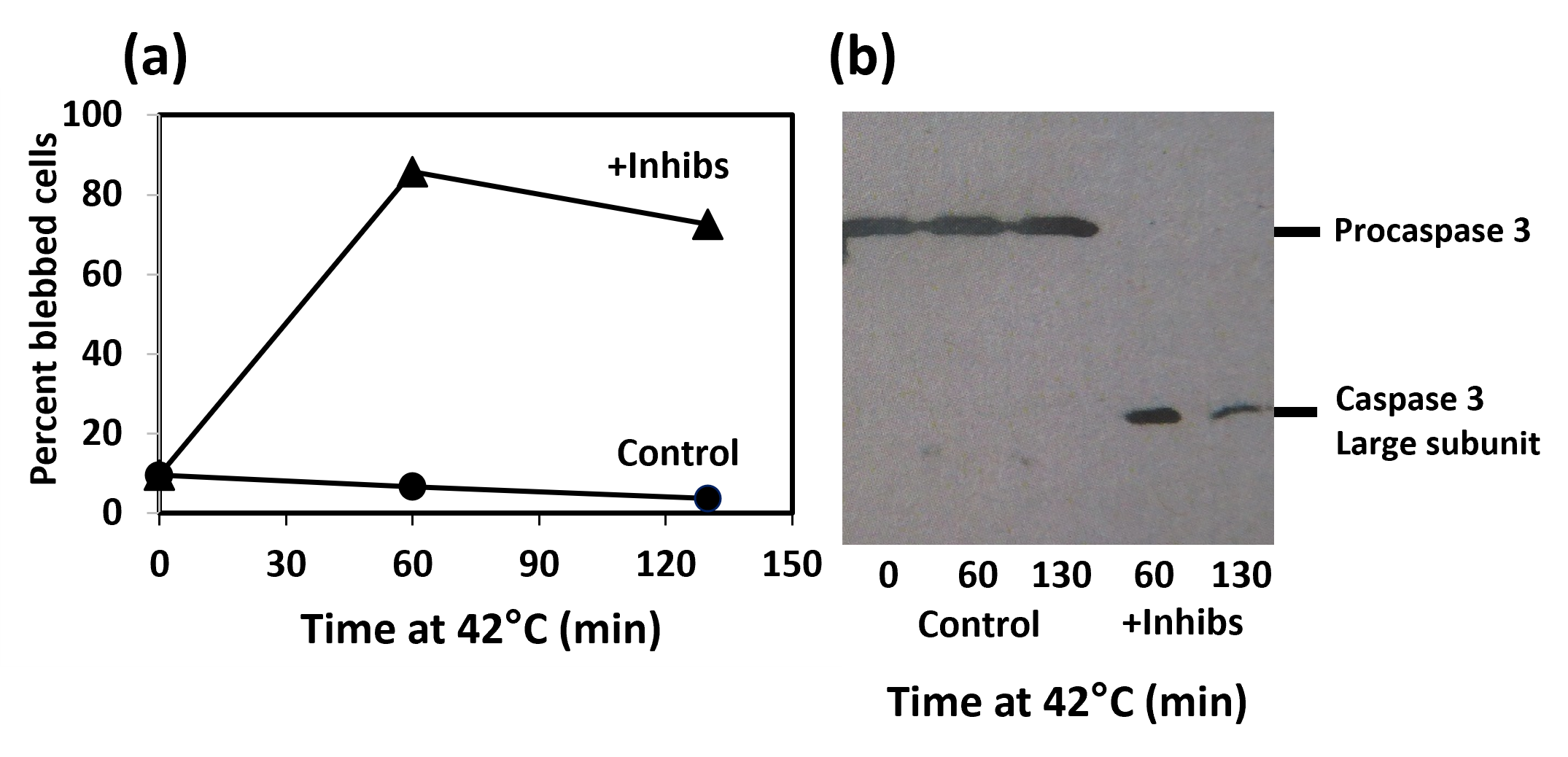

An example is presented in (Figure 10). (Figure 10a) shows the time course of appearance of apoptotic cells when interphase HeLa S3 are treated at 42°C, and when they are treated at 42°C in the presence of 5 μM each of ABT-199 and S63845. The western blot in Figure 10b confirms that apoptosis is occurring because procaspase 3 is undergoing cleavage.

Figure 10. Induction of apoptosis in interphase HeLa cells treated at 42°C with both ABT-199 and S63845. (a) Time course of appearance of apoptotic cells. Control, cells treated at 42°C without inhibitors (???); +Inhibs, cells treated at 42°C with 5 μM ABT-199 and 5 μM S63845 (???). (b) Western blot using an antibody to caspase 3, showing that procaspase 3 is intact in the control but cleaved and activated in the drug-treated cells..

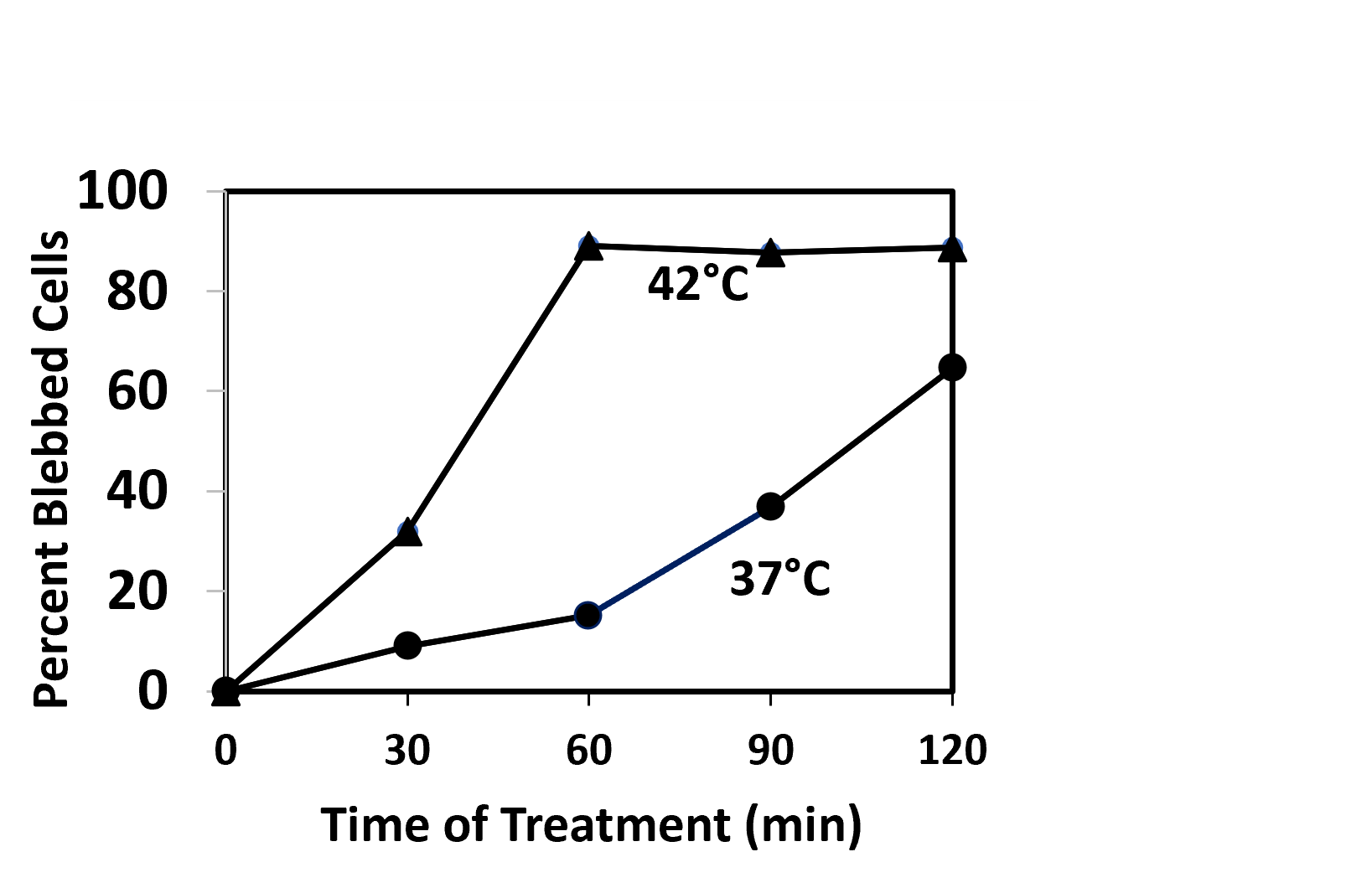

The control in (Figure 10a) shows that apoptosis is not induced by hyperthermia in the absence of drugs. However, if we want to combine systemic drug treatment with localized hyperthermia, a more important question is whether apoptosis is induced by the drugs in the absence of hyperthermia. In this case, the answer is not so favorable. The rate of induction of apoptosis (cell blebbing) is less at 37°C than at 42°C, but it is still significant (Figure 11). After 60 min treatment, 88% of the cells are blebbed in the sample treated at 42°C and 15% are blebbed at 37°C. The percentage of apoptotic cells in the 37°C culture continues to rise after that.

Figure 11. Induction of apoptosis (plasma membrane blebbing) in interphase HeLa S3 cells treated with 10 μM ABT-199 and 10 μM S63845 at 42°C (???) and at 37°C (???).

Again, the ideal would be to find a drug that has no negative effects at 37°C. However, if that cannot be done, there may be a way around the problem, such as cooling the body during the treatment, injecting the drug or drugs directly into the tumor instead of administering them systemically, or using a drug that has a short lifetime in the body.

In conclusion, we cannot yet make any suggestion for a useful cancer therapy, but there are hints that one might be possible. It is a possibility that will be worth investigating further.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh for its continuing support. The early stages of work reported here were supported by grants GM-39915 and GM-46040 from the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Public Health Service.

References

2. Green DR. The Coming Decade of Cell Death Research: Five Riddles. Cell. 2019 May 16;177(5):1094-107.

3. Tang D, Kang R, Berghe TV, Vandenabeele P, Kroemer G. The molecular machinery of regulated cell death. Cell Res. 2019 May;29(5):347-64.

4. Green DR. Apoptotic pathways: the roads to ruin. Cell. 1998 Sep 18;94(6):695-8.

5. Song Z, Steller H. Death by design: mechanism and control of apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 1999 Dec;9(12):M49-52.

6. Bratton SB, MacFarlane M, Cain K, Cohen GM. Protein complexes activate distinct caspase cascades in death receptor and stress-induced apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2000 Apr 10;256(1):27-33.

7. Enari M, Sakahira H, Yokoyama H, Okawa K, Iwamatsu A, Nagata S. A caspase-activated DNase that degrades DNA during apoptosis, and its inhibitor ICAD. Nature. 1998 Jan 1;391(6662):43-50.

8. Thornberry NA, Lazebnik Y. Caspases: enemies within. Science. 1998 Aug 28;281(5381):1312-6.

9. Earnshaw WC, Martins LM, Kaufmann SH. Mammalian caspases: structure, activation, substrates, and functions during apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:383-424.

10. Nagata S. Apoptotic DNA fragmentation. Exp Cell Res. 2000 Apr 10;256(1):12-8.

11. Hickman JA. Apoptosis induced by anticancer drugs. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1992 Sep;11(2):121-39.

12. Cotter TG, Glynn JM, Echeverri F, Green DR. The induction of apoptosis by chemotherapeutic agents occurs in all phases of the cell cycle. Anticancer Res. 1992 May-Jun;12(3):773-9.

13. Bamford M, Walkinshaw G, Brown R. Therapeutic applications of apoptosis research. Exp Cell Res. 2000 Apr 10;256(1):1-11.

14. Kaufmann SH, Earnshaw WC. Induction of apoptosis by cancer chemotherapy. Exp Cell Res. 2000 Apr 10;256(1):42-9.

15. Reed JC. Apoptosis-based therapies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002 Feb;1(2):111-21.

16. Harmon BV, Takano YS, Winterford CM, Gobé GC. The role of apoptosis in the response of cells and tumours to mild hyperthermia. Int J Radiat Biol. 1991 Feb;59(2):489-501.

17. Falk MH, Issels RD. Hyperthermia in oncology. Int J Hyperthermia. 2001 Jan-Feb;17(1):1-18.

18. Eikesdal HP, Bjerkvig R, Raleigh JA, Mella O, Dahl O. Tumor vasculature is targeted by the combination of combretastatin A-4 and hyperthermia. Radiother Oncol. 2001 Dec;61(3):313-20.

19. Murata R, Overgaard J, Horsman MR. Combretastatin A-4 disodium phosphate: a vascular targeting agent that improves that improves the anti-tumor effects of hyperthermia, radiation, and mild thermoradiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001 Nov 15;51(4):1018-24.

20. Alexander HR Jr. Hyperthermia and its modern use in cancer treatment. Cancer. 2003 Jul 15;98(2):219-21.

21. Hildebrandt B, Wust P. The biologic rationale of hyperthermia. Cancer Treat Res. 2007;134:171-84.

22. DeNardo GL, DeNardo SJ. Update: Turning the heat on cancer. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2008 Dec;23(6):671-80.

23. Ahmed K, Zaidi SF. Treating cancer with heat: hyperthermia as promising strategy to enhance apoptosis. J Pak Med Assoc. 2013 Apr;63(4):504-8.

24. Ahmed K, Tabuchi Y, Kondo T. Hyperthermia: an effective strategy to induce apoptosis in cancer cells. Apoptosis. 2015 Nov;20(11):1411-9.

25. Paulson JR, Kresch AK, Mesner PW. Moderate hyperthermia induces apoptosis in metaphase-arrested cells but not in interphase HeLa cells. Adv Biol Chem. 2016;6:126-39.

26. Paulson JR, Luedtke RL, Suydam S, Obi D, Xie L. ABT-263, an Inhibitor of Bcl-2 Family Antiapoptotic Proteins, Sensitizes Prometaphase-Arrested HeLa Cells to Apoptosis Induced by Mild Hyperthermia. Int J Biochem Res Rev. 2022;31(6):23-34.

27. Medappa KC, McLean C, Rueckert RR. On the structure of rhinovirus 1A. Virology. 1971 May;44(2):259-70.

28. Paulson JR, Patzlaff JS, Vallis AJ. Evidence that the endogenous histone H1 phosphatase in HeLa mitotic chromosomes is protein phosphatase 1, not protein phosphatase 2A. J Cell Sci. 1996 Jun;109 ( Pt 6):1437-47.

29. Norbury C, Nurse P. Animal cell cycles and their control. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:441-70.

30. Gadbois DM, Hamaguchi JR, Swank RA, Bradbury EM. Staurosporine is a potent inhibitor of p34cdc2 and p34cdc2-like kinases. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992 Apr 15;184(1):80-5.

31. Mineo C, Murakami Y, Ishimi Y, Hanaoka F, Yamada M. Isolation and analysis of a mammalian temperature-sensitive mutant defective in G2 functions. Exp Cell Res. 1986 Nov;167(1):53-62.

32. Paulson JR. Inactivation of Cdk1/Cyclin B in metaphase-arrested mouse FT210 cells induces exit from mitosis without chromosome segregation or cytokinesis and allows passage through another cell cycle. Chromosoma. 2007 Apr;116(2):215-25.

33. Keaton JM, Workman BG, Xie L, Paulson JR. Analog-sensitive Cdk1 as a tool to study mitotic exit: protein phosphatase 1 is required downstream from Cdk1 inactivation in budding yeast. Chromosome Res. 2023 Sep 10;31(3):27-42.

34. Slee EA, Zhu H, Chow SC, MacFarlane M, Nicholson DW, Cohen GM. Benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp (OMe) fluoromethylketone (Z-VAD.FMK) inhibits apoptosis by blocking the processing of CPP32. Biochem J. 1996 Apr 1;315 ( Pt 1)(Pt 1):21-4.

35. Han CR, Jun do Y, Lee JY, Kim YH. Prometaphase arrest-dependent phosphorylation of Bcl-2 and Bim reduces the association of Bcl-2 with Bak or Bim, provoking Bak activation and mitochondrial apoptosis in nocodazole-treated Jurkat T cells. Apoptosis. 2014 Jan;19(1):224-40.

36. Tse C, Shoemaker AR, Adickes J, Anderson MG, Chen J, Jin S, et al. ABT-263: a potent and orally bioavailable Bcl-2 family inhibitor. Cancer Res. 2008 May 1;68(9):3421-8.

37. Ishihara H, Martin BL, Brautigan DL, Karaki H, Ozaki H, Kato Y, et al. Calyculin A and okadaic acid: inhibitors of protein phosphatase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989 Mar 31;159(3):871-7.

38. Chartier L, Rankin LL, Allen RE, Kato Y, Fusetani N, Karaki H, et al. Calyculin-A increases the level of protein phosphorylation and changes the shape of 3T3 fibroblasts. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 1991;18(1):26-40.

39. Paulson JR, Vander Mause ER. Calyculin A induces prematurely condensed chromosomes without histone H1 phosphorylation in mammalian G1-phase cells. Adv Biol Chem 2013; 3:36-43.

40. Nguyen M, Marcellus RC, Roulston A, Watson M, Serfass L, Murthy Madiraju SR, et al. Small molecule obatoclax (GX15-070) antagonizes MCL-1 and overcomes MCL-1-mediated resistance to apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Dec 4;104(49):19512-7.

41. Konopleva M, Watt J, Contractor R, Tsao T, Harris D, Estrov Z, et al. Mechanisms of antileukemic activity of the novel Bcl-2 homology domain-3 mimetic GX15-070 (obatoclax). Cancer Res. 2008 May 1;68(9):3413-20.

42. Vandenberg CJ, Cory S. ABT-199, a new Bcl-2-specific BH3 mimetic, has in vivo efficacy against aggressive Myc-driven mouse lymphomas without provoking thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2013 Mar 21;121(12):2285-8.

43. Souers AJ, Leverson JD, Boghaert ER, Ackler SL, Catron ND, Chen J, et al. ABT-199, a potent and selective BCL-2 inhibitor, achieves antitumor activity while sparing platelets. Nat Med. 2013 Feb;19(2):202-8.

44. Seymour J. Venetoclax, the first BCL-2 inhibitor for use in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2019 Aug;17(8):440-3.

45. Cao Q, Wu X, Zhang Q, Gong J, Chen Y, You Y, et al. Mechanisms of action of the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax in multiple myeloma: a literature review. Front Pharmacol. 2023 Nov 6;14:1291920.

46. Letai A. S63845, an MCL-1 Selective BH3 Mimetic: Another Arrow in Our Quiver. Cancer Cell. 2016 Dec 12;30(6):834-5.

47. Szlavik Z, Csekei M, Paczal A, Szabo ZB, Sipos S, Radics G, et al. Discovery of S64315, a Potent and Selective Mcl-1 Inhibitor. J Med Chem. 2020 Nov 25;63(22):13762-95.

48. Li Z, He S, Look AT. The MCL1-specific inhibitor S63845 acts synergistically with venetoclax/ABT-199 to induce apoptosis in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Leukemia. 2019 Jan;33(1):262-6.

49. Gavathiotis E, Reyna DE, Bellairs JA, Leshchiner ES, Walensky LD. Direct and selective small-molecule activation of proapoptotic BAX. Nat Chem Biol. 2012 Jul;8(7):639-45.

50. Ruchaud S, Carmena M, Earnshaw WC. The chromosomal passenger complex: one for all and all for one. Cell. 2007 Oct 19;131(2):230-1.

51. Rauch A, Hennig D, Schäfer C, Wirth M, Marx C, Heinzel T, et al. Survivin and YM155: how faithful is the liaison? Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014 Apr;1845(2):202-20.

52. Vogler M, Dinsdale D, Dyer MJ, Cohen GM. Bcl-2 inhibitors: small molecules with a big impact on cancer therapy. Cell Death Differ. 2009 Mar;16(3):360-7.

53. Kang MH, Reynolds CP. Bcl-2 inhibitors: targeting mitochondrial apoptotic pathways in cancer therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009 Feb 15;15(4):1126-32.

54. Garner TP, Lopez A, Reyna DE, Spitz AZ, Gavathiotis E. Progress in targeting the BCL-2 family of proteins. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2017 Aug;39:133-42.

55. Timucin AC, Basaga H, Kutuk O. Selective targeting of antiapoptotic BCL-2 proteins in cancer. Med Res Rev. 2019 Jan;39(1):146-75.

56. Konrad CG. Protein synthesis and RNA synthesis during mitosis in animal cells. J Cell Biol. 1963 Nov;19(2):267-77.

57. Leresche A, Wolf VJ, Gottesfeld JM. Repression of RNA polymerase II and III transcription during M phase of the cell cycle. Exp Cell Res. 1996 Dec 15;229(2):282-8