Abstract

The Apolipoprotein L1 gene (APOL1) has two risk variants crucial for innate immunity against pathogens, such as Trypanosoma and HIV. Still, it is also linked to diseases like preterm birth, pre-eclampsia, cardiovascular diseases, and systemic lupus erythematosus, which are often worsened by environmental factors or infections called "second hits." Kidney disease appears in adolescents and young adults with risk alleles, increasing the risk of kidney failure. No current treatment exists for APOL1 nephropathy. These variants are absent in individuals of Indian descent despite a history of migrations. The review highlights the role of genetics and epigenetics in APOL1 research and screening, with a focus on the absence of risk alleles in the Indian population.

Keywords

APOL1, ESRD, Genetics, Epigenetics, G1 and G2 variants

Introduction

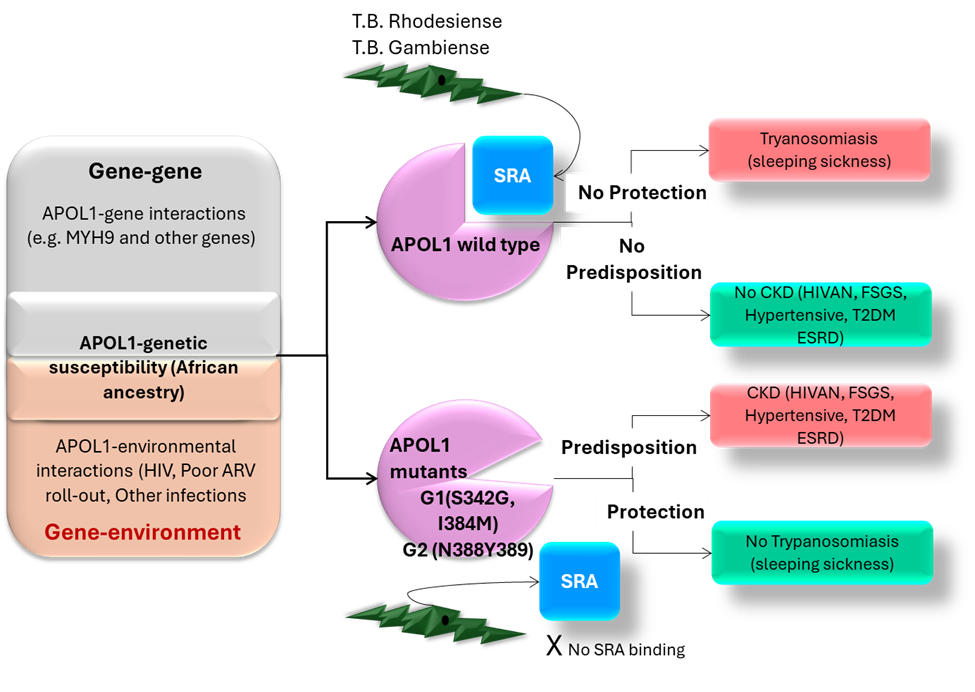

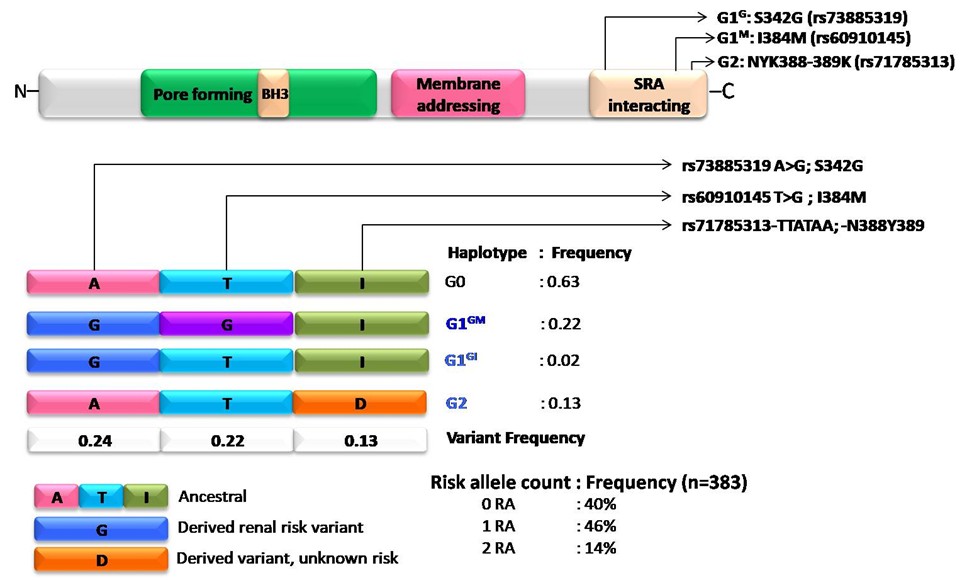

The APOL gene cluster on chromosome 22q12 comprises six genes that originated through duplication, suggesting adaptation. Within APOL1, key variants G1 (with two single-nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) and G2 (a six-base pair deletion) emerged approximately 60,000 years ago as a protective mechanism against trypanosomal infections in Africa. Carriers of both risk alleles have a higher risk of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) due to recessive inheritance. The non-risk allele G0 was identified, with G1 and G2 variants discovered in 2010. G1 features two amino acid substitutions, while G2 has a two-amino-acid deletion. Approximately six million African Americans carry these genotypes (Figure 1) [1–3].

The G1 allele, present in approximately 23% of individuals of African ancestry, comprises two missense variants, G1G (p.S342G) and G1M (p.I384M), which are nearly always co-occurring [4]. There are 62 protein-altering variants across six APOL genes with a minor allele frequency of over 0.1% in African populations [5]. The G2 allele, with a 14% MAF, has a 6-base pair deletion. The APOL1 gene encodes Apolipoprotein L1 (ApoL1), which protects against African trypanosomiasis by destroying trypanosomes [6]. These variants arose independently and are only 12 base pairs apart, preventing recombination [7].

Recent data indicate that G1 and G2 APOL1 variants are most prevalent in Western Africa, particularly in Ghana and Nigeria [8], with G1 frequencies exceeding 40% and G2 frequencies ranging from 6% to 24%. These alleles show gradients from west to east and from south to north. Originating in sub-Saharan Africa over 10,000 years ago, they underwent strong positive selection. Only the Yoruba in Nigeria show evidence of a recent selective sweep related to these alleles [9].

The APOL1 G1 and G2 variants are primarily found outside Africa, particularly among people of recent African ancestry due to the trans-Atlantic slave trade, which transported over 11 million Africans to the Americas and the Caribbean. Research shows that 20% to 22% of African American chromosomes carry the G1 variants, 13% to 15% have the G2 variants, and 10% to 15% carry both risk alleles, reflecting the significant impact of this historical event on genetic distribution [10]. Hispanic populations in New York with African ancestry show lower frequencies of specific risk alleles. Research has identified APOL1 variants in various ethnic groups in Israel, where African ancestry may not be readily apparent. Israel's Jewish population, including Ashkenazi, Sephardi, North African, and Mizrahi Jews, shares closer ancestry with each other than with their non-Jewish neighbors, suggesting a Levantine origin [7,11–13]. APOL1 variants are most prevalent in West Africa, particularly in Ghana and Nigeria, where positive selection is likely to have occurred within the past 10,000 years (Figure 2) [4].

A new variant, APOL3 (p.Q58*), significantly increases the risk of chronic kidney disease (CKD), even when considering APOL1 G1/G2 carrier status [4] and in APOL1 G1/G2 monoallelic patients, indicating an epistatic interaction and a protective role of wild-type APOL3. This variant is common in individuals at risk of CKD, especially those with APOL1 alleles, underscoring the genetic importance.

APO-L1 Function

APOL1 is a trypanolytic toxin [14] that requires TLFs (trypanosome lytic factors) and HPR (haptoglobin-related protein) for its activity [15,16]. The selectivity of APOL1 (Apolipoprotein L1) channels presents a fascinating complexity, intricately tied to the surrounding pH levels, and showcases a remarkable duality in ion permeability. At Low pH (Acidic Environment), the APOL1 unveils its role as an anion-selective channel, seamlessly facilitating the passage of chloride ions. This mechanism is crucial, as it enables APOL1 to integrate into the endosomal membranes of Trypanosoma brucei, ultimately leading to the dramatic lysis of these parasites. At Neutral pH, APOL1 has established a foothold at lower pH levels; a shift to a neutral environment like that found within the plasma membrane triggers a remarkable transformation. At this stage, APOL1 morphs into a cation-selective channel, allowing the influx of vital ions such as potassium, sodium, and possibly calcium. This dual functionality highlights its adaptability across different cellular landscapes. To summarize this, it may be emphasized that there exists a pH-switchable selectivity. The protein effortlessly adjusts its ion selectivity, responding dynamically to fluctuations in pH, a testament to its sophisticated structural versatility. However, there is conflicting data and models; despite the insights gained, it's essential to recognize the ongoing debates and divergences within the scientific community regarding the precise mechanisms governing anion versus cation selectivity. The pursuit of understanding continues, revealing layers of complexity in APOL1's function.

The importance of lipid environment

The role of negatively charged phospholipids cannot be understated; they form a crucial backdrop for APOL1's membrane insertion and its dual permease activities. The interplay between APOL1 and these lipids is a key aspect of its functionality. One may summarize that APOL1's ion selectivity is not merely a passive characteristic but a dynamic, evolving process finely tuned by the pH of its environment. This adaptability enables APOL1 to fulfill multiple roles in various cellular compartments, contributing to its remarkable trypanolytic capabilities while also presenting potential nephrotoxic risks, weaving a complex narrative of biological interaction and response.

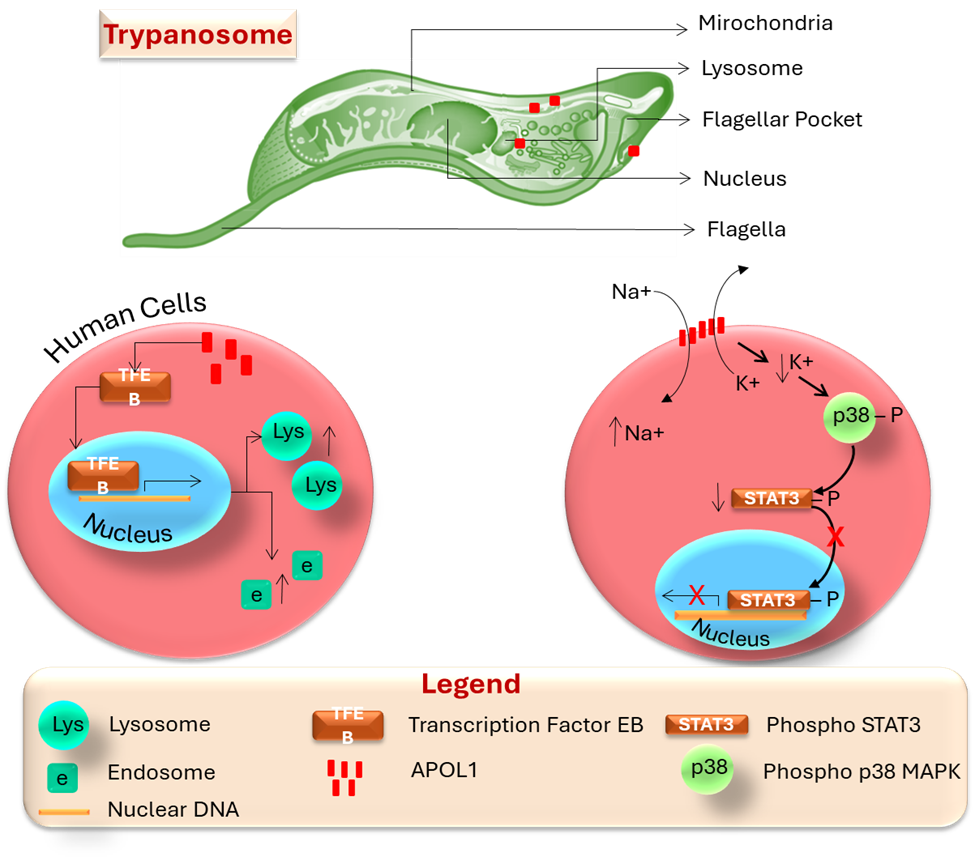

APOL1 shows limited similarity to bacterial colicins, which are toxic proteins [17]. It undergoes conformational changes in acidic endosomes and lysosomes, possibly leading to chloride influx and channel activity in the plasma membrane [16]. Some studies indicate it remains inactive under acidic conditions and functions at physiological pH [18]. Sodium influx through APOL1 can cause osmotic stress and cytoplasmic swelling, contributing to trypanolysis, while oxidative stress is also linked to its activity [19]. Its lysosomal localization may serve a detoxifying role rather than directly lysing parasites [19]. Some APOL1-containing endosomes traffic to mitochondria, inducing membrane permeabilization and DNA fragmentation in trypanosomes. Although APOL1 exhibits pore-forming activity, discrepancies exist regarding its channel selectivity and the effects of pH [20]. The trypanolytic mechanism of APOL1 remains unclear, involving potential processes such as membrane disruption, osmotic lysis, and apoptosis-like cell death associated with APOL1-related kidney injury. APOL1 enters trypanosomes via HDL3 endocytosis, traffics to the lysosome, and activates lysosomal swelling for trypanolysis. It may also affect the plasma membrane or mitochondria. In human cells, APOL1 promotes TFEB movement to the nucleus, thereby enhancing lysosomal biogenesis and restricting HIV-1 replication. Overexpressed APOL1-G1 and G2 localize to the plasma membrane, inducing potassium efflux, activating p38 MAPK, and inhibiting gp130-STAT3 signaling, with this effect observed mainly in the presence of kidney disease risk variants (Figure 3).

APOL1 tissue and cellular distribution

APOL1 is a trypanolytic toxin linked to focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS), particularly with the G1 and G2 variants [23]. The gene is expressed in various tissues, including the kidneys [21], suggesting a local role in addition to its immune functions. While APOL1 variants may increase disease risk, levels of circulating APOL1 and HDL did not correlate with kidney disease in specific African American cohorts [22]. Studies have demonstrated [23] that the risk of graft loss is related to the genotype of the transplanted kidneys, rather than the recipient. The APOL1 protein is found in podocytes and proximal tubules, with reduced levels observed in FSGS [24] and HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) [25]. The presence of APOL1 in renal cells beyond the glomerulus suggests potential roles in kidney diseases, although its specific functions remain unclear [26].

Apolipoprotein L1 (APOL1) is a trypanolytic protein that has resistance mechanisms [27] against two subspecies of Trypanosoma brucei: T.b. rhodesiense, associated with acute sleeping sickness in East Africa, and T.b. gambiense, linked to chronic sleeping sickness in West Africa. The G1 risk allele is associated with an asymptomatic carrier state for T.b. gambiense, while the G2 allele protects against T.b. rhodesiense. APOL1 functions as an ion channel, with varying roles based on pH and lipid environment. Risk variants may cause nephrotoxicity by increasing transcription of IL-1 and IL-18. Despite many carrying high-risk APOL1 variants, only 20% develop kidney disease, suggesting that environmental factors, like high interferon levels from viral infections, are involved. There is a lack of data on risk alleles from India [28].

APOL1 Expression and Upstream Regulation

The expression of the APOL1 gene constitutes a critical area of investigation in comprehending the onset and progression of APOL1-mediated nephropathy, especially among individuals of recent African ancestry who possess particular risk variants. The inheritance mode in APOL1-Mediated Kidney Disease (AMKD) is a genetic condition where specific mutations in the APOL1 gene increase the risk of kidney disease, particularly in individuals of Western and Central African descent [29]. AMKD is not a single disease, but a range of kidney conditions linked to APOL1 mutations, including FSGS, hypertension-related kidney disease, membranous nephropathy, and nephrotic syndrome. Currently, there are no FDA-approved treatments specifically for AMKD; however, clinical trials are ongoing to discover and evaluate potential therapies. Recognizing AMKD is vital for early detection, management, and possibly preventing kidney failure. The American Kidney Fund promotes awareness and encourages genetic testing for at-risk populations. Unlike typical autosomal recessive disorders caused by loss-of-function mutations, APOL1-related kidney disease follows a recessive pattern with gain-of-function characteristics. Recent research involving small-molecule inhibitors and antisense oligonucleotides aimed at reducing APOL1 expression supports this gain-of-function hypothesis [2]. The pathogenesis is a matter of controversy. Certain variations in the APOL1 gene, known as risk variants (G1 and G2), are linked to a higher risk of developing kidney disease. Individuals with two copies of these risk variants (one from each parent) have a significantly higher chance of developing kidney disease, including conditions like focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) and HIV-associated nephropathy. People of Black/African American, Afro-Caribbean, and Hispanic/Latino descent are more likely to have these APOL1 risk variants.

The functional APOL1 gene is present in some African primates but is not essential for normal kidney function [29], as individuals without it can still maintain healthy kidneys. Inhibiting APOL1 toxicity could improve kidney disease without significant side effects; however, caution is needed until its impact on other systems, such as the endothelium and immune cells, is fully understood. Additionally, lowering APOL1 expression may have negative consequences in areas where trypanosomiasis is common [30].

APOL1 expression is regulated by a complex interplay of genetic and epigenetic factors, as well as various immune and inflammatory pathways, particularly the interferon family [31]. Key transcription factors, such as STAT2 and STAT3, as well as several interferon-regulating factors, interact with the APOL1 promoter, leading to a dramatic increase in expression of up to 200-fold in response to specific stimuli [32]. Comparative analyses reveal that Toll-like receptor 3 activation has a greater impact on APOL1 than receptor 4, while interferon-γ significantly influences expression more than interferon-β and α. These findings highlight the role of APOL1 in cellular immune responses.

The JAK/STAT pathway regulates immune and adaptive responses, involving four JAK members (JAK1–JAK3 and receptor tyrosine kinase 2) and seven STAT members (STAT1–STAT4, STAT5a, STAT5b, and STAT6). Recent studies have linked significant activation of this pathway to kidney diseases, including diabetic nephropathy and COVID-19-associated nephropathy. In the latter, cytokines such as interleukin-6 and interleukin-1β activate the JAK/STAT signaling pathway [33], leading to increased APOL1 expression in human podocytes and glomerular endothelial cells, even at low interferon levels, indicating that interferon-independent mechanisms may contribute to podocyte injury [34]. Baricitinib, a JAK inhibitor, may mitigate APOL1-induced cellular damage, suggesting its potential therapeutic value [35].

Host genetic factors can affect APOL1 expression. Gain-of-function mutations in the stimulator of interferon genes (STING) enhance interferon production, leading to STING-associated vasculopathy, which typically begins in infancy. This creates a feedback loop involving JAK1 and STAT1/STAT2, which promotes the transcription of proinflammatory genes. A case report highlighted a patient with APOL1 G1 and G2 risk alleles who had a high interferon state due to STING-associated vasculopathy, linked to collapsing glomerulopathy [36].

Research shows that epigenetics, copy number variants, and SNPs influence APOL1-associated nephropathy. Key genetic modifiers include SMOC2, DEF1B, UBD, NUDT7, and GSTB1. Environmental factors, such as air pollution, are also associated with the onset of AMKD in individuals with APOL1 risk variants, likely due to cellular stress. Overall, AMKD exhibits a diverse range of clinical manifestations that are shaped by the interplay between genetic and environmental factors.

APOL1 and Podocyte Injury

A leading hypothesis suggests that APOL1 mediates injury as an ion channel, with debate over whether these channels are anionic or cationic. This discrepancy arises from differences in localization (cellular vs. organelle) and model specificity (trypanosome vs. podocyte toxicity), as well as factors such as pH. While APOL1's subcellular localization and binding partners are well-documented, a consensus across models is still lacking [37].

Research shows that APOL1 forms anion-selective pores in vesicular membranes, allowing chloride influx that causes water retention and swelling in trypanosomes. Other studies indicate that for APOL1 to open cation channels, an acidic pH is required. This leads to membrane depolarization and the death of the trypanosome. Mammalian cells with APOL1 risk variants exhibit increased cation permeability, leading to potassium loss and cell damage through stress-activated protein kinases. Overall, APOL1's ion channel selectivity varies with pH: it is chloride-permeable at pH five and potassium-permeable at neutral pH, influenced by pH, negatively charged phospholipids, and low ionic strength [38].

APOL1-Associated Endoplasmic Reticulum and Lysosomal Stress

Lysosomes and the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) are affected by APOL1-related cell damage. Risk variants of APOL1 increase lysosomal permeability and disrupt endo-lysosomal trafficking, resulting in cellular disturbances. When APOL1 integrates into the lysosomal membrane, it triggers an influx of ions, leading to cell death. G1 and G2 variants reduce the lysosomal count in podocytes, leading to enzyme leakage into the cytoplasm [41]. Recent studies indicate that APOL1 is mainly localized to the ER. Chun et al. found that APOL1 risk variants localize in the ER, while wild-type APOL1 is found in lipid droplets. The promotion of lipid droplet formation shifts G1 and G2 variants to lipid droplets, thereby decreasing autophagic flux and increasing cytotoxicity. Tissue hypoxia, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation can worsen ER stress and kidney disease in individuals with high-risk APOL1 variants. Further research is needed to explore ER stress mechanisms and their impact on disease progression, as targeting ER stress may offer therapeutic strategies applicable to other conditions like cancer and metabolic disorders.

Inflammation and APOL1

Inflammatory processes trigger the expression of APOL1, contributing to cellular damage. STING, an endoplasmic reticulum protein [42], detects cyclic dinucleotides from cyclic GMP-AMP synthase during stress. When cytoplasmic double-stranded DNA is present, this enzyme produces 2′,3′-cGAMP, activating STING and releasing type I interferons and pro-inflammatory cytokines. Excessive activation of STING can lead to necroptosis, apoptosis, and lysosomal fragmentation through the NLRP3 inflammasome, which activates inflammatory proteins such as interleukin-1β and gasdermin D, ultimately resulting in cellular damage. Recent studies have focused on the role of the STING-NLRP3 pathway in APOL1-related cytotoxicity and have targeted this signaling pathway for new therapies in chronic inflammation models, including cancer and autoimmune diseases.

Other Mechanisms

APOL1-mediated cellular damage arises from complex molecular interactions. In addition to the previously mentioned mechanisms [43], AMKD involves the activation of protein kinase R during viral infections, increased autophagic cell death via the BCL2-homology 3 domain of APOL1, and alterations in the ubiquitin-proteasome system, resulting in the prolonged intracellular retention of proteins such as APOL1. The APOL1 G1 and G2 variants also bind strongly to suPAR-activated αvβ3 integrin on podocytes, contributing to the progression of chronic kidney disease [29].

The rapid progress in drug repurposing, systems biology, and artificial intelligence within nephrology is leading to innovative approaches for addressing APOL1-mediated renal injury in Acute Muscle Kidney Disease. Table 1 outlines the Phase 1 to 3 clinical trials. Small molecules are potent pharmacological agents that specifically target enzymes or protein interactions related to disease pathways. Their lower molecular weight enables better cellular penetration, reducing off-target effects and toxicity to healthy cells. This makes them promise personalized medicine in AMKD, as patients may have unique molecular disease drivers. Additionally, many small-molecule inhibitors exhibit good oral bioavailability, making them easily administered. The small-molecule inhibitor targeting the APOL1 channel, VX-147 (inaxaplin), has shown promise in reducing proteinuria in patients with APOL1-associated focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). In a Phase 2a study of 16 participants with high-risk APOL1 variants and biopsy-confirmed FSGS, those who adhered to the treatment for 13 weeks experienced a 47.6% average decrease in the urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio. Inaxaplin (VX-147) is a promising first-in-class oral small molecule that inhibits APOL1 channel activity, currently undergoing Phase 2/3 trials for AMKD. It targets the root cause of AMKD by blocking the APOL1 protein's function, which is involved in the development of certain kidney conditions. The drug has demonstrated potential in reducing proteinuria and decelerating kidney disease progression in patients with specific APOL1 gene variants. However, despite these positive signs, the limited sample size and possible biases in the study restrict definitive conclusions, and there are ongoing concerns about the long-term effectiveness of inaxaplin. In a Phase 2a study, inaxaplin treatment led to a notable decrease in proteinuria, excess protein in the urine, which is a crucial marker of kidney damage in a group of patients with AMKD. By addressing the root cause of AMKD and lowering proteinuria, inaxaplin may slow kidney disease progression and prevent additional structural damage.

|

Drug |

Phase |

Completion |

Mechanism of action |

Status |

NCT number |

|

VX-147 |

Phase 2 |

December 2021 |

APOL1 channel blocker (small molecule inhibitor) |

Completed |

NCT04340362 |

|

Phase 2/3 |

June 2026 |

Recruiting |

NCT05312879 |

||

|

VX-840 |

Phase 1 |

November 2022 |

APOL1 channel blocker (small molecule inhibitor) |

Completed |

NCT05324410 |

|

AZD2373 |

Phase 1 |

August 2021 |

APOL1 antisense oligonucleotide |

Completed |

NCT04269031 |

|

Phase 1 |

July 2023 |

Active, not recruiting |

NCT05351047 |

||

|

Baricitinib |

Phase 2 |

March 2026 |

Janus Kinase-STAT Inhibition |

Recruiting |

NCT05237388 |

|

Different mechanisms of phase 1, 2, 3 trials, their completion date, and final status. (APOL1: Apolipoprotein L1; STAT: Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription.) Search of clinicaltrials.gov was performed on July 19, 2023. |

|||||

A larger Phase 2/3 study is in progress, alongside another small-molecule inhibitor, VX-840. Additionally, MZ-301 targets APOL1 currents, reducing cytotoxicity and decreasing urine albumin-to-creatinine ratios in APOL1 G2 mutant mice [44].

Antisense Oligonucleotides

Oligonucleotide therapeutics, including antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), are gaining increasing importance in nephrology. The generation 2.5 APOL1 ASO (IONIS-APOL1Rx) has shown strong in vitro and in vivo activity in APOL1 G1-transgenic mice [45]. Subcutaneous administration resulted in dose-dependent reductions in kidney and liver APOL1 mRNA and prevented interferon-induced proteinuria. Currently, it is part of a Phase I study assessing safety and pharmacokinetics, with results pending.

JAK/STAT Pathway Blockade

The JAK/STAT pathway is crucial for proinflammatory cell activation, and its inhibition may reduce APOL1-related toxicity [33], as indicated by promising preclinical results [46]. A phase 2 trial (JUSTICE, NCT05237388) is evaluating the efficacy of baricitinib, a JAK inhibitor approved for rheumatoid arthritis and alopecia areata, in patients with AMKD [47]. Additionally, the next-generation ASO 2.5 is being explored for inhibiting STAT3, which suppresses gene expression by blocking translation or promoting degradation of the DNA-RNA heteroduplex. AZD9150 is under investigation for its effects in leukemia and lymphoma [48].

APOL1 Status in the Indian Subcontinent

A report on APOL1 null alleles in a rural Indian village found no link to glomerulosclerosis, suggesting that this absence among the population may indicate different mechanisms at play for glomerulosclerosis in African Americans. A 2016 study by Yadav et al. also found APOL1 G1 and G2 variants unlikely to explain chronic kidney disease (CKD) in their Indian cohort. However, further research on diverse ethnic and tribal groups in India is needed to confirm the absence of APOL1 variants in the region. While significant advances have been made in understanding APOL1, many questions remain, highlighting the need for further studies on its impact on renal disease and pre-eclampsia [49,50]. Another point to keep in mind is the inflow of patients with CKD from the African subcontinent, who may be tested for APOL1 mutations.

The recent and ongoing APOL1 therapeutic trials are illustrated in Table 1. Currently, the focus is on including participants with recent African ancestry, as they are more likely to possess the risk variants associated with APOL1. Participants often undergo APOL1 genetic testing, utilizing blood or saliva samples, to identify those carrying the risk variants. Most important is to develop and evaluate treatments, including medications that specifically target the APOL1 protein or aim to mitigate the downstream effects of the genetic variations. Certain studies focus on understanding the implications of APOL1 variants on kidney transplant outcomes, such as the survival of transplanted kidneys and the recurrence of kidney disease post-transplant. Further, these clinical trials shed light on the understanding of disease mechanisms. Further, these trials also consider patient attitudes regarding APOL1 genetic testing and how such knowledge influences their health management strategies.

Examples of ongoing clinical trials beyond the table are related to APOL1, which illustrates the APOLLO Study: Sponsored by the NIH, this study investigates the effects of APOL1 risk variants on kidney transplant outcomes from both deceased and living donors. The Yale Medicine Trial deals with assessing an investigational medication for AMKD in non-diabetic individuals with kidney disease. Duke Nephrology Trial: Focused on African American/Black adults with non-diabetic kidney failure (FSGS), this trial aims to understand how APOL1 gene variations lead to kidney disease. APOL1 Genotyping CTA Clinical Performance Study: This trial involves identifying individuals with high-risk APOL1 genotypes to evaluate the safety and efficacy of an antisense oligonucleotide aimed at treating AMKD.

GUARDD-US Trial: This investigation examines whether awareness of the APOL1 genotype can lead to better blood pressure management in individuals possessing two risk alleles. The findings from these trials have the potential to significantly enhance the quality of life for individuals suffering from APOL1-associated kidney disease, reducing health disparities. Insights gained from this research can guide clinical practices and improve care strategies for patients affected by AMKD.

Future Directions and Considerations

Research has identified cellular pathways activated by APOL1 risk variants, but gaps remain in our understanding. Less than 30% of individuals with two high-risk APOL1 variants develop AMKD, prompting investigations into "second hits" and suitable patient populations for genetic screening. This could help reduce adverse kidney outcomes and support the development of biomarkers and personalized therapies. Key questions include the effects of circulating APOL1 on the kidneys and whether lowering systemic levels or inhibiting mutant APOL1 is more effective in treating the condition. Different strategies may be necessary for various AMKD subgroups, particularly in regions endemic for trypanosomiasis, due to potential off-target effects. Improving kidney-specific drug delivery is essential. Overall, while progress has been made, further research is needed in molecular sub-phenotyping and the safety and efficacy of new treatments, especially in India, where chronic kidney disease is increasingly prevalent.

Conclusion

The APOL1 gene's risk alleles are associated with increased hypertension and early kidney dysfunction in young adults, though the lifetime risk in pediatric populations is less clear. Ongoing research is essential for understanding the implications of genetic screening in children and young adults, as the risk of kidney disease rises with age. Key questions persist regarding the most at-risk populations and the genetic and environmental factors influencing kidney disease onset. Recent studies have also demonstrated that APOL1 plays a role in innate immunity, with its overexpression in podocytes leading to symptoms like those observed in humans, providing insights into related disease pathways.

Acknowledgment

The author thanks Mr. Sanjay Kumar Johari for his assistance in preparing this manuscript at all stages.

References

2. Friedman DJ, Pollak MR. APOL1 Nephropathy: From Genetics to Clinical Applications. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021 Feb 8;16(2):294–303.

3. Robinson-Cohen C. Functional Assessment of High-Risk APOL1 Genetic Variants. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022 May;17(5):626–27.

4. Zhang DY, Levin MG, Duda JT, Landry LG, Witschey WR, Damrauer SM, at al. Protein-truncating variant in APOL3 increases chronic kidney disease risk in epistasis with APOL1 risk alleles. JCI Insight. 2024 Oct 8;9(19):e181238.

5. Coker MM, Akinyemi RO, Bakare AA, Owolabi MO. Genetic Epidemiology and Associated Diseases of APOL1: A Narrative Review. West Afr J Med. 2021 Jun 26;38(6):511–19.

6. Raghubeer S, Pillay TS, Matsha TE. Gene of the month: APOL1. J Clin Pathol. 2020 Aug;73(8):441–43.

7. Limou S, Nelson GW, Kopp JB, Winkler CA. APOL1 kidney risk alleles: population genetics and disease associations. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2014 Sep;21(5):426–33.

8. Kabore NF, Cournil A, Poda A, Ciaffi L, Binns-Roemer E, David V, et al. APOL1 Renal Risk Variants and Kidney Function in HIV-1-Infected People From Sub-Saharan Africa. Kidney Int Rep. 2021 Oct 16;7(3):483–93.

9. Wudil UJ, Aliyu MH, Prigmore HL, Ingles DJ, Ahonkhai AA, Musa BM, et al. Apolipoprotein-1 risk variants and associated kidney phenotypes in an adult HIV cohort in Nigeria. Kidney Int. 2021 Jul;100(1):146–54.

10. Breeze CE, Lin BM, Winkler CA, Franceschini N. African ancestry-derived APOL1 risk genotypes show proximal epigenetic associations. BMC Genomics. 2024 May 8;25(1):452.

11. Ben-Ruby D, Atias-Varon D, Kagan M, Chowers G, Shlomovitz O, Slabodnik-Kaner K, et al. Multiethnic prevalence of the APOL1 G1 and G2 variants among the Israeli dialysis population. Clin Kidney J. 2024 Dec 6;18(2):sfae397

12. Behar DM, Yunusbayev B, Metspalu M, Metspalu E, Rosset S, Parik J, et al. The genome-wide structure of the Jewish people. Nature. 2010 Jul 8;466(7303):238–42.

13. Genovese G, Friedman DJ, Ross MD, Lecordier L, Uzureau P, Freedman BI, et al. Association of trypanolytic ApoL1 variants with kidney disease in African Americans. Science. 2010 Aug 13;329(5993):841–5.

14. Pays E, Vanhollebeke B, Uzureau P, Lecordier L, Pérez-Morga D. The molecular arms race between African trypanosomes and humans. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014 Aug;12(8):575–84.

15. Harrington JM, Howell S, Hajduk SL. Membrane permeabilization by trypanosome lytic factor, a cytolytic human high density lipoprotein. J Biol Chem. 2009 May 15;284(20):13505–12.

16. Pérez-Morga D, Vanhollebeke B, Paturiaux-Hanocq F, Nolan DP, Lins L, Homblé F, et al. Apolipoprotein L-I promotes trypanosome lysis by forming pores in lysosomal membranes. Science. 2005 Jul 15;309(5733):469–72.

17. Molina-Portela Mdel P, Lugli EB, Recio-Pinto E, Raper J. Trypanosome lytic factor, a subclass of high-density lipoprotein, forms cation-selective pores in membranes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2005 Dec;144(2):218–26.

18. Greene AS, Hajduk SL. Trypanosome Lytic Factor-1 Initiates Oxidation-stimulated Osmotic Lysis of Trypanosoma brucei brucei. J Biol Chem. 2016 Feb 5;291(6):3063–75.

19. Vanwalleghem G, Fontaine F, Lecordier L, Tebabi P, Klewe K, Nolan DP, et al. Coupling of lysosomal and mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in trypanolysis by APOL1. Nat Commun. 2015 Aug 26;6:8078.

20. Thomson R, Finkelstein A. Human trypanolytic factor APOL1 forms pH-gated cation-selective channels in planar lipid bilayers: relevance to trypanosome lysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015 Mar 3;112(9):2894–9.

21. Monajemi H, Fontijn RD, Pannekoek H, Horrevoets AJ. The apolipoprotein L gene cluster has emerged recently in evolution and is expressed in human vascular tissue. Genomics. 2002 Apr;79(4):539–46.

22. Bruggeman LA, O'Toole JF, Ross MD, Madhavan SM, Smurzynski M, Wu K, et al. Plasma apolipoprotein L1 levels do not correlate with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Mar;25(3):634–44.

23. Reeves-Daniel AM, DePalma JA, Bleyer AJ, Rocco MV, Murea M, Adams PL, et al. The APOL1 gene and allograft survival after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2011 May;11(5):1025–30.

24. Ma L, Shelness GS, Snipes JA, Murea M, Antinozzi PA, Cheng D, et al. Localization of APOL1 protein and mRNA in the human kidney: nondiseased tissue, primary cells, and immortalized cell lines. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015 Feb;26(2):339–48.

25. Kotb AM, Simon O, Blumenthal A, Vogelgesang S, Dombrowski F, Amann K, et al. Knockdown of ApoL1 in Zebrafish Larvae Affects the Glomerular Filtration Barrier and the Expression of Nephrin. PLoS One. 2016 May 3;11(5):e0153768.

26. Madhavan SM, O'Toole JF, Konieczkowski M, Ganesan S, Bruggeman LA, Sedor JR. APOL1 localization in normal kidney and nondiabetic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011 Nov;22(11):2119–28.

27. O'Toole JF, Bruggeman LA, Madhavan S, Sedor JR. The Cell Biology of APOL1. Semin Nephrol. 2017 Nov;37(6):538–45.

28. Mohanasundaram S, Fernando ME. Apolipoprotein L1 Genetic Testing in Prospective Kidney Donors: Have We Reached a Breakthrough or an Impasse?. Indian Journal of Transplantation. 2023 Jul 1;17(3):275–8.

29. Vasquez-Rios G, De Cos M, Campbell KN. Novel Therapies in APOL1-Mediated Kidney Disease: From Molecular Pathways to Therapeutic Options. Kidney Int Rep. 2023 Aug 29;8(11):2226–34.

30. Cooper A, Ilboudo H, Alibu VP, Ravel S, Enyaru J, Weir W, et al. APOL1 renal risk variants have contrasting resistance and susceptibility associations with African trypanosomiasis. Elife. 2017 May 24;6:e25461.

31. Pollak MR, Friedman DJ. APOL1-associated kidney disease: modulators of the genotype-phenotype relationship. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2025 May 1;34(3):191–8.

32. Nichols B, Jog P, Lee JH, Blackler D, Wilmot M, D'Agati V, et al. Innate immunity pathways regulate the nephropathy gene Apolipoprotein L1. Kidney Int. 2015 Feb;87(2):332–42.

33. Brosius FC 3rd, He JC. JAK inhibition and progressive kidney disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015 Jan;24(1):88–95.

34. Hoilat GJ, Das G, Shahnawaz M, Shanley P, Bukhari SH. COVID-19 induced collapsing glomerulopathy and role of APOL1. QJM. 2021 Jul 28;114(4):263–4.

35. Nystrom SE, Li G, Datta S, Soldano KL, Silas D, Weins A, et al. JAK inhibitor blocks COVID-19 cytokine-induced JAK/STAT/APOL1 signaling in glomerular cells and podocytopathy in human kidney organoids. JCI Insight. 2022 Jun 8;7(11):e157432.

36. Abid Q, Best Rocha A, Larsen CP, Schulert G, Marsh R, Yasin S, et al. APOL1-Associated Collapsing Focal Segmental Glomerulosclerosis in a Patient With Stimulator of Interferon Genes (STING)-Associated Vasculopathy With Onset in Infancy (SAVI). Am J Kidney Dis. 2020 Feb;75(2):287–90.

37. Shah SS, Lannon H, Dias L, Zhang JY, Alper SL, Pollak MR, et al. APOL1 Kidney Risk Variants Induce Cell Death via Mitochondrial Translocation and Opening of the Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Pore. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019 Dec;30(12):2355–68.

38. Chen TK, Surapaneni AL, Arking DE, Ballantyne CM, Boerwinkle E, Chen J, et al. APOL1 Kidney Risk Variants and Proteomics. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022 May;17(5):684–92.

39. Blazer A, Qian Y, Schlegel MP, Algasas H, Buyon JP, Cadwell K, et al. APOL1 variant-expressing endothelial cells exhibit autophagic dysfunction and mitochondrial stress. Front Genet. 2022 Sep 27;13:769936.

40. Gerstner L, Chen M, Kampf LL, Milosavljevic J, Lang K, Schneider R, et al. Inhibition of endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling rescues cytotoxicity of human apolipoprotein-L1 risk variants in Drosophila. Kidney Int. 2022 Jun;101(6):1216–31.

41. Chun J, Zhang JY, Wilkins MS, Subramanian B, Riella C, Magraner JM, et al. Recruitment of APOL1 kidney disease risk variants to lipid droplets attenuates cell toxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019 Feb 26;116(9):3712–21.

42. Bruggeman LA, Sedor JR, O'Toole JF. Apolipoprotein L1 and mechanisms of kidney disease susceptibility. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2021 May 1;30(3):317–23.

43. Zimmerman B, Dakin LA, Fortier A, Nanou E, Blasio A, Mann J, et al. Small molecule APOL1 inhibitors as a precision medicine approach for APOL1-mediated kidney disease. Nat Commun. 2025 Jan 2;16(1):167.

44. Egbuna O, Zimmerman B, Manos G, Fortier A, Chirieac MC, Dakin LA, et al. Inaxaplin for Proteinuric Kidney Disease in Persons with Two APOL1 Variants. N Engl J Med. 2023 Mar 16;388(11):969–79.

45. Aghajan M, Booten SL, Althage M, Hart CE, Ericsson A, Maxvall I, et al. Antisense oligonucleotide treatment ameliorates IFN-γ-induced proteinuria in APOL1-transgenic mice. JCI Insight. 2019 Jun 20;4(12):e126124.

46. Paz-Barba M, Muñoz Garcia A, de Winter TJJ, de Graaf N, van Agen M, van der Sar E, et al. Apolipoprotein L genes are novel mediators of inflammation in beta cells. Diabetologia. 2024 Jan;67(1):124–36.

47. Olabisi OA, Barrett NJ, Lucas A, Smith M, Bethea K, Soldano K, et al. Design and Rationale of the Phase 2 Baricitinib Study in Apolipoprotein L1-Mediated Kidney Disease (JUSTICE). Kidney Int Rep. 2024 Jun 27;9(9):2677–84.

48. Huang Z, Lei W, Hu HB, Zhang H, Zhu Y. H19 promotes non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) development through STAT3 signaling via sponging miR-17. J Cell Physiol. 2018 Oct;233(10):6768–76.

49. Johnstone DB, Shegokar V, Nihalani D, Rathore YS, Mallik L, Ashish, et al. APOL1 null alleles from a rural village in India do not correlate with glomerulosclerosis. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e51546.

50. Kumar V, Yadav AK, Gang S, John O, Modi GK, Ojha JP, et al. Indian chronic kidney disease study: Design and methods. Nephrology (Carlton). 2017 Apr;22(4):273–78.