Abstract

Sutures play an important role in wound healing. The search for more appropriate suture material has resulted in a variety of natural and synthetic, absorbable and non-absorbable sutures available commercially. These features influence biological reactions to the sutures. Surgical trauma and the presence of foreign body material, both induce inflammatory tissue reaction surrounding sutures causing damages to the tissue defenses, infection, delay in coordinated onset of the proliferative phase and impairs optimum wound healing, also causing excessive scar tissue which is associated with poor wound strength.

Study aimed to compare the biological reactions (intensity of inflammation, neo-vascularization, and fibrosis formation) to four different suture materials silk, polypropylene [Prolene], polyamide [nylon], and polyglactin [Vicryl]) implanted in the subcutaneous tissue of guinea pigs and decide on suture material having better effect on wound healing. Assessment was done for histopathological evaluation on light microscope.

Study was conducted at central animal house, a tertiary care medical college in western Maharashtra, India. It involved 25 healthy adult guinea pigs, randomly divided into five groups, with 4 groups receiving different suture materials and 1 control group. Age (P=0.97), weight (P=0.96) across the groups showed no significant differences, ensuring uniformity in the physical condition of the subjects.

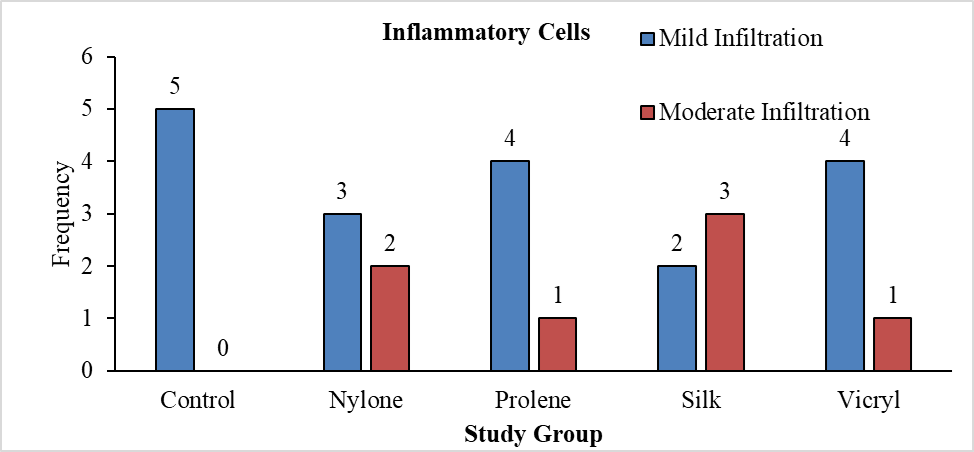

Inflammatory response- silk showed the highest moderate infiltration (60%), followed by nylon (40%). However, differences in inflammation levels among the groups were not statistically significant (P=0.271).

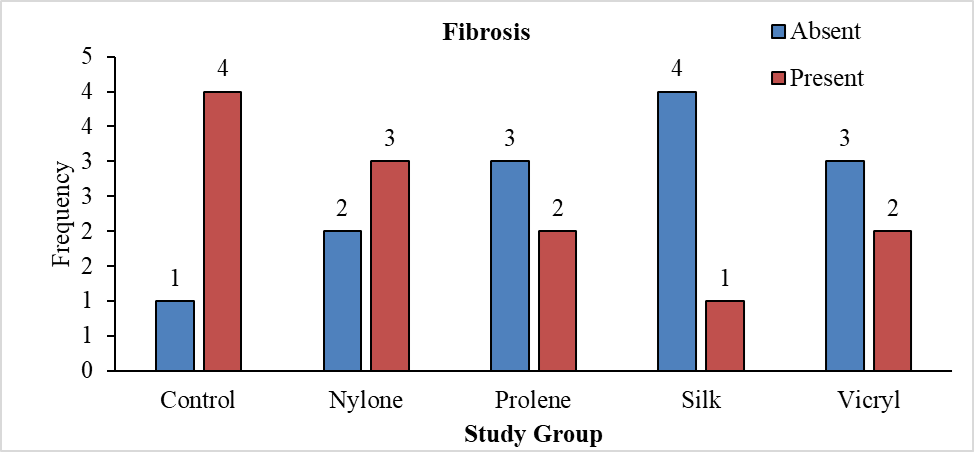

Fibrosis- were present in most animals, with no significant differences across the groups (P=0.384).

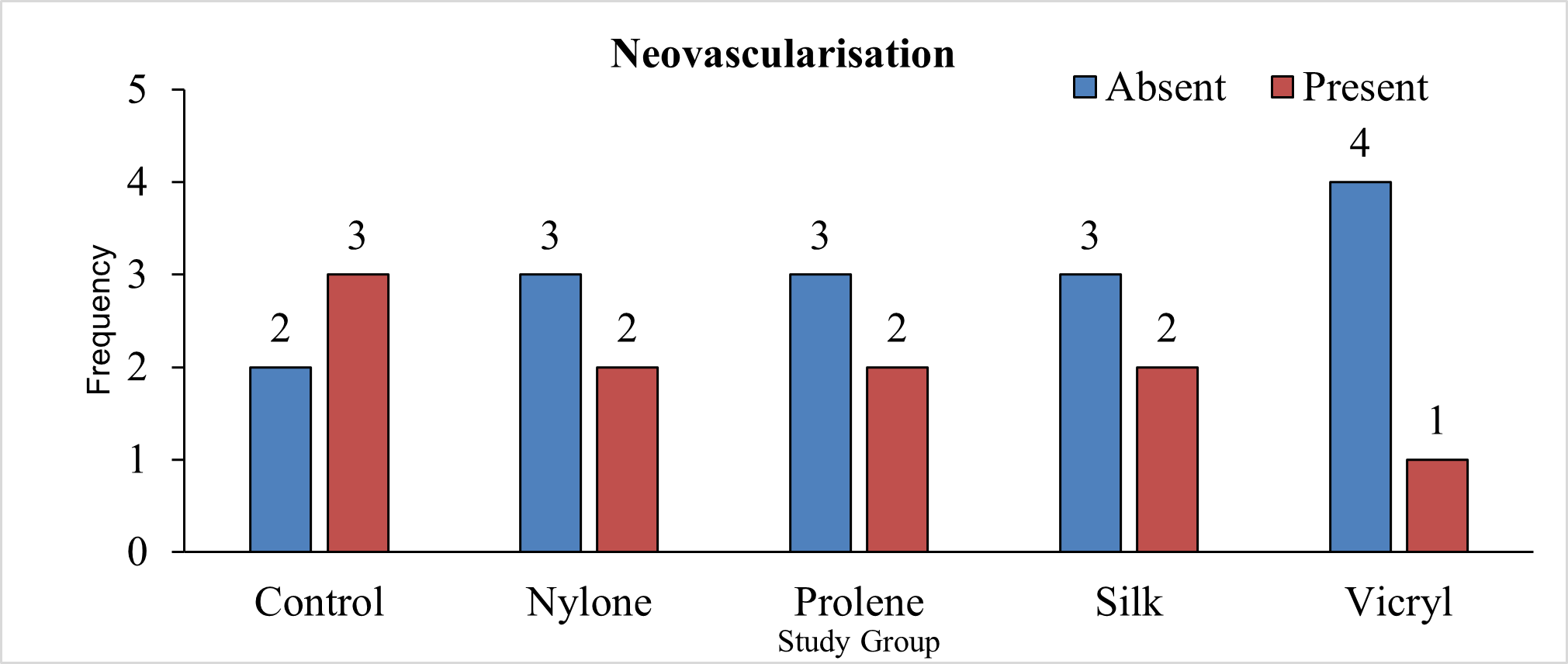

Neovascularization- were observed in all groups, with vicryl showing the highest absence (80%) and the control group showing a balanced distribution. Variations were not statistically significant (P=0.797). Gross findings like visible sutures, erythema, swelling, seroma, suture extrusion, wound dehiscence, stitch abscess were not observed in any study animals, indicating good biocompatibility.

There were no statistically significant differences among the suture materials in terms of inflammatory cell infiltration, fibrosis formation, neovascularization. Also, no significant gross findings. This suggests that all the tested suture materials show similar levels of biocompatibility and minimal adverse reactions when used in the subcutaneous tissue of guinea pigs.

Keywords

Suture materials, Biological reactions, Inflammatory reaction, Fibrosis, Neovascularization, Wound healing

Background

The surgical experience from around 3,000 years BC led to the development of the synthetic suture materials used today. Plant fibres, hair, tendons, and wool threads—all of which have been discovered in mummified remains—were used by the ancient Egyptians for sutures. Edwin smith (1822–1906) found a papyrus containing medical knowledge that had been codified around 1,600 BC. The papyrus containing smith's name is a roll that is more than 15 feet long and has 48 drawings of medical remedies for trauma along with more than 500 lines of text [1].

Of the 48 cases that are detailed in depth on the papyrus, some refer to sutures. For instance, the papyrus states, "if thou findest that wound open and its stitching loose, thou shouldst draw together the gash for him with two strips of linen" in reference to how to treat a laceration [2]. This type of suturing was commonly used by Egyptian embalmers to close up a body following organ removal [3].

Many materials have been used as suture materials in the past, and some are still in use today. These materials include gold, silver, iron and steel wires, dried animal intestines, animal hair (such as horsehair), silk, tree bark, and plant fibres (such as linen and cotton). Many synthetic biomaterials, including polydioxanone and poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid), have been used as suture materials in the recent past [4].

There isn't a single suture material that would be appropriate for every kind of surgical and medical need, even with the abundance of suture materials available. The variety of biomedical uses for sutures has increased thanks to improved suture design and materials. The potential for clinical and surgical applications of the latest developments and new trends in suture technology is enormous.

Material and Methods

Study was conducted in the Central Animal House, Department of General Surgery in a tertiary care hospital/medical college in western Maharashtra and study population consisted of healthy adult guinea pigs.

Sample included were 25 healthy adult guinea pigs divided into five groups of five animals each. Four groups received a different type of suture material (silk, polypropylene (Prolene), polyamide (Nylon), polyglactin (Vicryl), and one control group where no suture material were implanted.

Inclusion criteria

A. Species and strain: Guinea pig- Dunkin Hartley. B. Age and Weight: 42 to 70 days and 160–180 gms. C. Gender: Male/female. D. Number of days each animal be housed: 90 days. E. Healthy guinea pigs.

Exclusion criteria

A. Guinea pigs with pre-existing health conditions. B. Guinea pigs that had undergone any prior surgical procedure. C. Guinea pigs that did not meet the health standards set for the study.

Procedure

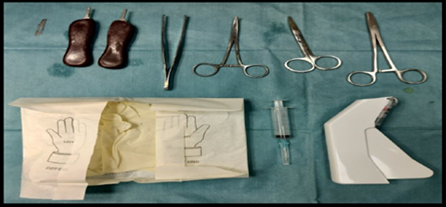

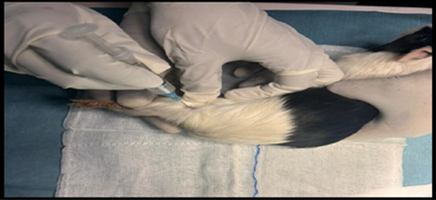

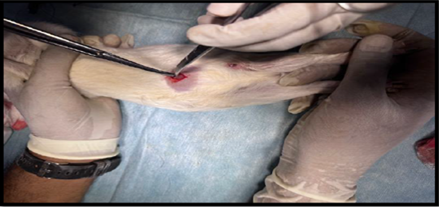

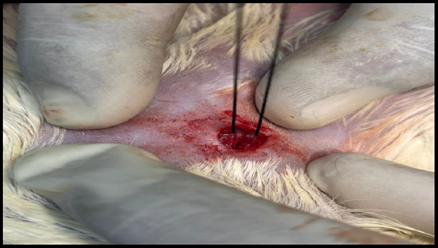

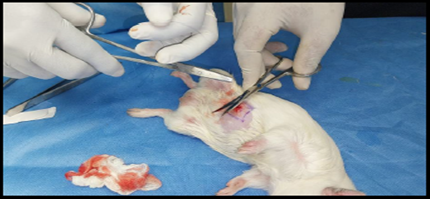

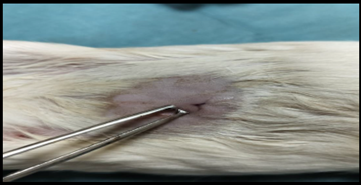

Healthy guinea pigs were selected and divided into five groups of five animals each. They were fed a standard laboratory diet throughout the study (Figure 1). Abdominal hairs of the guinea pigs were clipped, and surgical procedures were performed under local anaesthesia using lignocaine (4 mg/kg) after scrubbing the dorsal area with an antiseptic solution under strict aseptic precautions (Figure 3). A median incision of 01 cm (Figure 4) was made on the abdomen, and a subcutaneous pocket (Figure 5) was created. Specific suture material (silk, polypropylene, polyamide, polyglactin) was sutured to the subcutaneous tissue in the pocket created (Figure 7), with five animals in each group. Closure of the skin was done using staplers and sterile dressing applied (Figures 11 and 12). A control group of five animals had no intervention, where subcutaneous pocket was created, and no sutures were placed. Skin was closed with staplers and sterile dressing done (Figures 11 and 12). Staples were removed on the seventh day.

Figure 1. Guinea pigs housed separately.

Figure 2. Sterile instruments used in procedure.

Figure 3. Anaesthesia being given.

Figure 4. Incision (1 cm) given at abdomen.

Figure 5. Creation of subcutaneous pocket.

Figure 6. Subcutaneous pocket created.

Figure 7. Suture being applied.

Figure 8. Knotting of suture.

Figure 9. Suture placed at subcutaneous pocket.

Figure 10. Suture placed at subcutaneous pocket.

Figure 11. Skin closed.

Figure 12. Sterile dressing applied.

Figure 13. Post operatively monitored separately.

Figure 14. Post op day-21 showing previously sutured site.

Figure 15. Identification of previously sutured site at subcutaneous layer.

Any major complications of wound healing were checked, particularly within the first 7 days post-surgery. The study evaluated wound healing over 21 days and biopsy of the suture site was taken at three weeks post-procedure. Similar 1 cm incision was given at previously operated site and excision biopsy was taken from subcutaneous tissue (Figures 16 and 17). Assessment was done using light microscopy for histopathological examination. Tissue reactions next to the sutures were evaluated for the intensity of inflammatory cells, neovascularization, and fibrosis formation. Mt stain (Masson's trichrome) was used for microscopy study. Data were collected through digital photographs of the wound and histopathological examination then entered on excel sheet for analysis.

Figure 16. Excision of tissue from subcutaneous pocket.

Figure 17. Excised tissue kept in formalin.

Importance of biological compatibility

As the most used commonly surgical implants, sutures hold a 57% share of the global surgical equipment market. They fall into one of four categories: multifilament, monofilament, braided, or twisted. They can be made of synthetic or natural fibre biocompatible materials. Surgical sutures are very vulnerable to microbial colonization and bio film formation in addition to having the potential to cause a foreign body reaction [5–7].

The proper definition of biocompatibility has long been a source of contention [8,9]. In everyday speech, the phrase refers to a substance's capacity to coexist with human bodily tissue without endangering or poisoning it. Tissues and materials, however, can interact in a wide variety of ways. It is therefore exceedingly difficult to define the term "biocompatibility" in a single, comprehensive sense. The original implantable devices were designed to be nontoxic, non-carcinogenic and non-irritating between 1940 and 1980. As a result, this idea came to refer to materials that had to be resistant to deterioration and non-chemically reactive. The literature documented the procedures for screening polymers for biocompatibility, and it became more and more clear that a number of elements affected the application's effectiveness [10]. Later, this idea was reconsidered in light of the information that had been gathered from research investigations, both academic and clinical. It became clear that the biocompatibility of the material or device would change based on the clinical use or indication; also, the material or device should interact with tissue actively in certain applications and degrade over time in other circumstances.

"The ability of a material to perform with an appropriate host response in a specific application" was implied by the new paradigm for biocompatibility. According to this concept, the materials should not be passive but rather have a purpose. In order to accomplish this, the materials should cause a reaction in the tissue they come into touch with. Because of this, the idea of biocompatibility is constantly being discussed in the scientific community, and as long as biomaterials knowledge grows, new ideas and viewpoints will also be introduced and discussed [6,11].

Significance of light microscope

The principle of the light microscope (LM) is based upon the image obtained after a light is crossed through a thin sample and submitted to a system of lenses. It consists of an optical system with a tube with lenses on each tip: the ‘ocular’ near the eye and the ‘objective’ near the sample. To obtain total magnification, one must multiply the magnification of objective with the ocular’s one (generally 10×); so, with an ocular with a magnification of 10× and an objective with a magnification of 50×, the result is 500×. A system producing light is situated under the preparation. The sample is placed on a stage and the lenses can be adjusted in order to obtain a sharp image of the object and various biological reactions can be studied. LM assessment can be applied to study biological reactions to different suture materials in terms of surface morphology, fibrosis, cellular interactions, neovascularisation, inflammatory response, and foreign body response and are easily available, ease to use and easily reproducible with minimal expertise.

Justification

The choice of suture material in surgical procedures plays a pivotal role in the success of wound healing and patient outcomes. This experimental study focuses on elucidating the local tissue reactions to four commonly used suture materials, namely silk, polypropylene (Prolene), polyamide (Nylon), and polyglactin (Vicryl), when implanted in the subcutaneous tissue of guinea pigs. The comprehensive assessment aims to evaluate the degree of inflammation, neovascularization, and fibrosis formation at the sutured site. A completely reproducible system of light microscopic assessment was used for evaluation of microscopic analysis.

Understanding the intricate biological responses to these diverse suture materials is crucial for informed decision-making in clinical practice. The outcomes of this study will contribute valuable insights into the comparative effectiveness of these materials in promoting optimal wound healing. The microscopic assessment provides a high-resolution examination, allowing for a detailed exploration of cellular interactions with sutures, neovascularisation, fibrosis, inflammation and micro structural changes at the tissue-suture interface.

By comparing the biological reactions induced by each suture material in guinea pigs, this study aims to guide clinicians in selecting the most suitable material for specific surgical scenarios, ultimately enhancing the overall quality of patient care. The findings will provide a scientific basis for the informed selection of suture materials, promoting improved wound healing outcomes and minimizing complications associated with suboptimal material choices.

Evaluation criteria

The tissue reactions at the sutured site were evaluated for intensity of inflammatory cells, neo vascularization, and fibrosis formation.

Statistical analysis

Data entry was done using MS Excel and data analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS version 26.0. Means and proportions were calculated for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Categorical data was analysed using the students T test. Differences in proportions were assessed using the chi square test for statistical significance. A P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

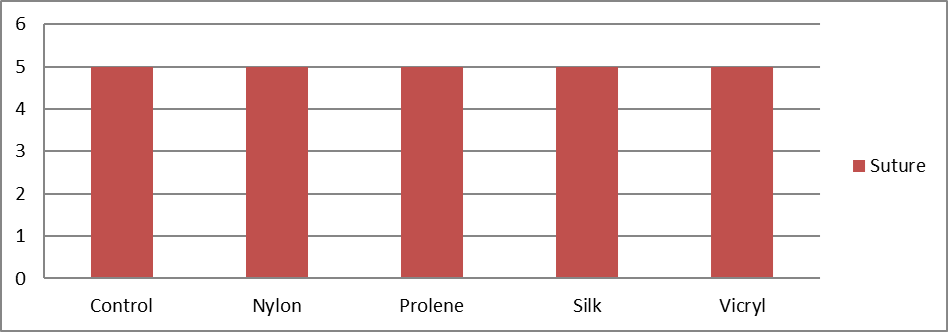

Table 1 presents the distribution of study animals based on the type of suture material applied. Each suture type was applied to 5 animals, representing 20% of the total sample for each group. This uniform distribution ensures an equal representation of each suture material in the study, allowing for a balanced comparison of their effects.

|

Suture Material |

Frequency (N) |

Percent (%) |

|

Control |

5 |

20.0 |

|

Nylon |

5 |

20.0 |

|

Prolene |

5 |

20.0 |

|

Silk |

5 |

20.0 |

|

Vicryl |

5 |

20.0 |

|

Total |

25 |

100.0 |

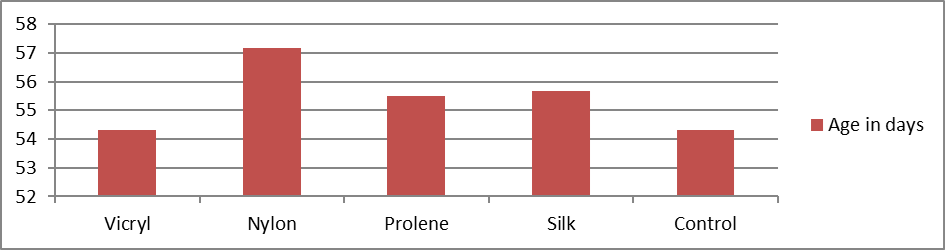

A total of 25 animals were included in the study. The mean age (in days) was 54.34. In the vicryl group the mean age was 54.33, 57.17 in nylon group, 55.50 in prolene group, 55.67 in silk and 54.33 in control groups. They were statistically insignificant with p value of 0.97 (Table 2).

Table 2. Distribution of study animals based on suture type applied (n=25).

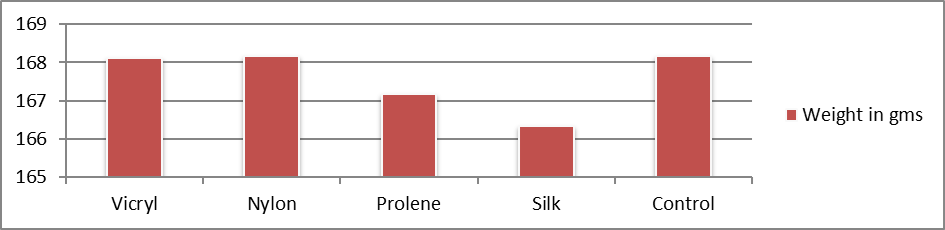

The mean weight (in gms) was 167.73. The mean weight was 168.17 in vicryl, nylon, and control groups, 167.17 in prolene group, and 166.33 in silk (Table 4). They were also statistically insignificant with p value of 0.96.

Table 4. Distribution of study groups based on weight of the animal (n = 25).

Table 5 illustrates the distribution of study groups based on the presence of inflammatory cells, with a total sample size of 25. The nylon group had 60% mild infiltration and 40% moderate infiltration, while the prolene group showed 80% mild and 20% moderate infiltration. The silk group presented 40% mild and 60% moderate infiltration, and the vicryl group had 80% mild and 20% moderate infiltration. The Chi square test was applied to test the statistical difference in proportions, yielding a p value of 0.271, indicating no significant difference in the presence of inflammatory cells among the study groups.

|

Study Group |

Presence of Inflammatory Cells |

Total |

P Value* |

|

|

Mild Infiltration (Less than 25 Cells) |

Moderate Infiltration (25 to 75 Cells) |

|||

|

Control |

5 (100.0) |

0 (0.0) |

5 (100.0) |

0.271 |

|

Nylon |

3 (60.0) |

2 (40.0) |

5 (100.0) |

|

|

Prolene |

4 (80.0) |

1 (20.0) |

5 (100.0) |

|

|

Silk |

2 (40.0) |

3 (60.0) |

5 (100.0) |

|

|

Vicryl |

4 (80.0) |

1 (20.0) |

5 (100.0) |

|

|

Total |

18 (72.0) |

7 (28.0) |

25 (100.0) |

|

|

* Chi square test was applied to test statistical difference in proportions |

||||

Table 7 shows the distribution of study groups based on the presence of fibrosis, with a total of 25 animals. In the control group, 20% of the animals showed an absence of fibrosis, while 80% showed its presence. The nylone group had 40% of animals without fibrosis and 60% with fibrosis. In the prolene group, 60% were without fibrosis and 40% had fibrosis. The silk group had 80% of animals without fibrosis and 20% with fibrosis. Lastly, the vicryl group showed 60% of animals without fibrosis and 40% with fibrosis. The chi square test for statistical difference in proportions resulted in a p-value of 0.384, indicating no significant difference in the presence of fibrosis among the study groups.

|

Study Group |

Presence of Fibrosis |

Total |

P Value* |

|

|

Absent |

Present |

|||

|

Control |

1 (20.0) |

4 (80.0) |

5 (100.0) |

0.384 |

|

Nylone |

2 (40.0) |

3 (60.0) |

5 (100.0) |

|

|

Prolene |

3 (60.0) |

2 (40.0) |

5 (100.0) |

|

|

Silk |

4 (80.0) |

1 (20.0) |

5 (100.0) |

|

|

Vicryl |

3 (60.0) |

2 (40.0) |

5 (100.0) |

|

|

Total |

13 (52.0) |

12 (48.0) |

25 (100.0) |

|

|

* Chi square test was applied to test statistical difference in proportions |

||||

Table 9 presents the distribution of study groups based on the presence of neovascularisation in a total of 25 animals. In the control group, 40% of animals showed an absence of neovascularisation, while 60% showed its presence. The nylone, prolene, and silk groups each had 60% of animals without neovascularisation and 40% with neovascularisation. The vicryl group exhibited 80% of animals without neovascularisation and 20% with neovascularisation. The chi square test for statistical difference in proportions resulted in a p-value of 0.797, indicating no significant difference in the presence of neovascularisation among the study groups.

|

Study Group |

Presence of Neovascularisation |

Total |

P Value* |

|

|

Absent |

Present |

|||

|

Control |

2 (40.0) |

3 (60.0) |

5 (100.0) |

0.797 |

|

Nylone |

3 (60.0) |

2 (40.0) |

5 (100.0) |

|

|

Prolene |

3 (60.0) |

2 (40.0) |

5 (100.0) |

|

|

Silk |

3 (60.0) |

2 (40.0) |

5 (100.0) |

|

|

Vicryl |

4 (80.0) |

1 (20.0) |

5 (100.0) |

|

|

Total |

15 (60.0) |

10 (40.0) |

25 (100.0) |

|

|

* Chi Square test was applied to test statistical difference in proportions |

||||

Gross findings

None of the study animals had visible sutures, erythema, swelling, seroma, extrusion of suture, wound dehiscence, or stitch abscess.

Discussion

This study aimed to compare the biological reactions to different suture materials (Silk, Polypropylene [Prolene], polyamide [Nylon], and polyglactin [Vicryl]) implanted in the subcutaneous tissue of guinea pigs. The assessment was based on the intensity of inflammation, neo vascularization, and fibrosis formation, involving 25 healthy adult guinea pigs divided into five groups.

The age distribution of the animals across the groups showed no significant difference (P=0.97), indicating a balanced age profile among the study groups (Table 3). Similarly, weight distribution was not significantly different (P=0.96) (Table 4), ensuring the uniformity of the subjects' physical conditions.

Table 3. Distribution of study groups based on age of the animal (n = 25).

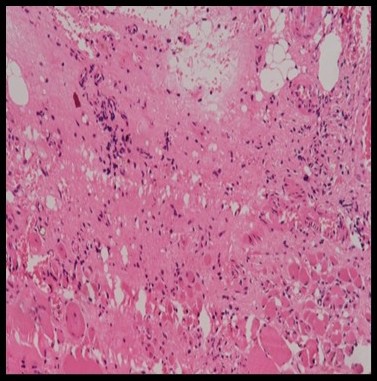

Histopathological evaluation revealed varying degrees of inflammatory cell infiltration. Silk showed the highest moderate infiltration of 60% and 40% of mid infiltration, followed by nylon 40% of moderate infiltration (Figure 19) and 60% mild infiltration, while the prolene group showed 80% mild and 20% moderate infiltration, vicryl showed 80% of mild infiltration and 20% of moderate infiltration and control group showed 100% of mild infiltration (Figure 18). However, the differences in inflammation levels among the groups were not statistically significant (P=0.271) (Tables 5 and 6).

Figure 19. HPE showing moderate inflammatory cells on nylon at 20x magnification (Table 6).

Figure 18. HPE showing diffuse inflammatory cells at control group at 20x magnification (Table 6).

Figure 20. HPE showing moderate inflammatory cells (Table 6).

Table 6. Distribution of study groups based on presence of inflammatory cells (n = 25).

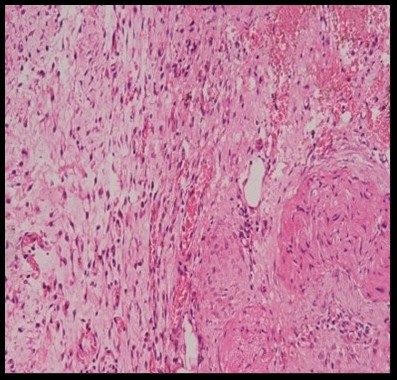

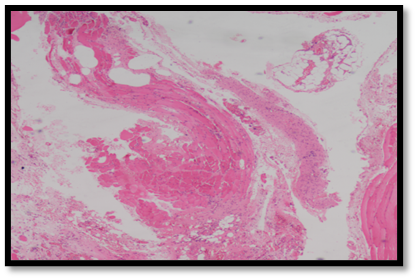

Fibrosis formation was present in most animals. In the control group, 20% of the animals showed an absence of fibrosis, while 80% showed its presence (Figure 21). Nylon group had 60% with fibrosis and 40% of animals without fibrosis. In the prolene group, 60% were without fibrosis and 40% had fibrosis. Silk group had 80% of animals without fibrosis and 20% with fibrosis. Lastly, the vicryl group showed 60% of animals without fibrosis and 40% with fibrosis. However, there with no significant difference across the groups (P=0.384) (Tables 7 and 8).

Figure 21. HPE showing dense fibrosis in control group at 10x magnification (Table 8).

Table 8. Distribution of study groups based on presence of fibrosis (n = 25).

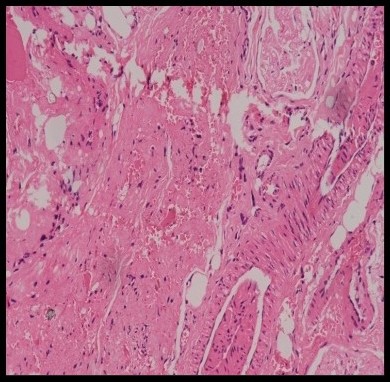

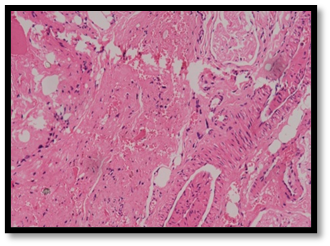

Neo vascularization, an essential component of wound healing, was observed in all groups. Vicryl group exhibited 80% of animals without neovascularisation and 20% with neovascularisation. In the control group, 40% of animals showed no neovascularisation, however, was seen in 60% (Figure 22). The nylone, prolene, and silk groups each had 60% of animals without neovascularisation and 40% with neovascularisation. However, these variations were not statistically significant (P=0.797) (Tables 9 and 10).

Figure 22. HPE showing presence of neovascularisation in control group at 10x magnification (Table 10).

Tabe 10. Distribution of study groups based on presence of neovascularisation (n = 25).

Notably, post procedure there were no visible sutures, erythema, swelling, seroma, suture extrusion, wound dehiscence, or stitch abscess were observed in any study animals. These findings suggest that all suture materials were biocompatible with guinea pig tissue. Wound healing is a multifaceted biological process regulated by multiple factors. The initial response of any tissue to sutures is prompted by the trauma created by the needle's passage, which causes a direct physical disruption. Following this, the tissue response to the specific polymers present in the suture materials becomes evident and various cellular and molecular mechanisms that contribute to the overall healing process, as the body interacts with the foreign materials introduced by the sutures [12]. Inflammatory response observed in the histological sections of the sutured tissue supports the notion that various inflammatory process occurring leads to subsequent hydrolysis of the suture material. The collagen fibres are found to be densely packed and oriented parallel to the suture material, indicating a structured formation of scar tissue around the sutures. This organized tissue response highlights the complex interplay between the inflammatory reaction and the healing process, further underscoring the importance of material biocompatibility in wound healing. In vitro studies have demonstrated that the polymers present in suture materials release soluble components. These components have been found to stimulate the production of cytokines by macrophages [13].

Based on the results of this study and considering findings from similar research, it is evident that the choice of suture material causing biological reactions within subcutaneous tissues varies. The histopathological evaluation in our study revealed varying levels of inflammatory cell infiltration, with silk exhibiting the highest moderate infiltration and nylon following closely behind. While these differences were not statistically significant, they underscore the nuanced tissue responses to different materials [14,15]. The results of our study showed varying degrees of inflammatory cell infiltration among different suture materials, with silk having the highest moderate infiltration (60%) and nylon following (40%). Kim et al. observed severe inflammatory infiltration for silk sutures within seven days, which decreased to moderate levels by fourteen days, particularly in the buccal mucosa. For nylon, our study found moderate infiltration, whereas Kim et al. [16] noted early infiltration by polymorphonuclear leukocytes transitioning to macrophages over time, with minimal inflammatory cells by fourteen days.

Similarly, the presence of fibrosis was observed uniformly across all groups, indicating consistent tissue reaction to the implanted sutures [14,15]. Neovascularization, a critical aspect of wound healing, was noted in all groups, with vicryl demonstrating the highest absence of this response compared to other materials. This observation aligns with previous studies that suggest vicryl induces milder tissue reactions, potentially due to its inherent properties that promote less severe inflammatory responses [14].

Our findings of fibrosis formation and neovascularization showed no significant differences across groups, similar to Kim et al.'s observation, that inflammatory responses in polyglycolic acid sutures were extensive but comparable over time [16]. Furthermore, it has been suggested that a suture's physical composition has a major impact on the intensity of the inflammatory response [17].

The 'wicking effect,' which promotes the spread of infection and the presence of bacteria within the suture, has been linked in numerous studies to the severe inflammation seen with multifilament sutures as opposed to monofilament sutures [18–20]. Grigg et al. [21] discovered that silk produced even less fluid flow by capillary action than coated vicryl or a polymer suture. There was no discernible infection with either kind of suture, according to a clinical investigation by Ivanoff and Windmark on the effects of suture absorption in two types of multifilament sutures and the ensuing difficulties in wound healing [22].

These findings align with our results, where no significant adverse reactions, such as erythema, swelling, seroma, suture extrusion, wound dehiscence, or stitch abscess, were observed in any of the study animals, indicating the biocompatibility of all suture materials used. According to a recent study, within three days of silk sutures being applied, the entire surface became contaminated by microorganisms. This was attributed to the wicking effect facilitated by the braided design of the sutures [23]. Complete absorption by seven days was also observed in earlier research [14,24–26], yet a recent study [27] found suture materials containing polyglycolic acid was absorbed eight days after suturing. Absorbable sutures may degrade and dissolve prematurely in some cases, while in others, they might persist in the incision area longer than desired [28,29]. They undergo resulting in varying degrees of tissue reaction [30].

Our study, after 21 days, no suture material was observed on both gross and microscopic findings. Numerous studies have compared how the skin of the body responds to various suture materials [14]. On the dorsal side of the rat's skin, Yaltirik et al. assessed the inflammatory response to silk, vicryl, polypropylene, and catgut [14]. They observed that vicryl sutures produced a comparatively milder inflammatory response in comparison to silk, polypropylene, and catgut sutures [31]. It appears that the inflammatory response is influenced more by the physical arrangement of the threads rather than their chemical composition, a fact that aligns with observations made by other researchers in the field [32–34]. Multifilament sutures exhibit increased peri-sutural tissue ingrowth was demonstrated in numerous other studies [35,36].

Conclusion

Results showed that there were no statistically significant differences among the suture materials in terms of inflammatory cell infiltration, fibrosis formation, neo vascularization. Also, no significant gross findings. This suggests that all the tested suture materials show similar levels of biocompatibility and minimal adverse reactions when used in the subcutaneous tissue of guinea pigs.

Recommendations

Studies with larger sample sizes and longer follow-up periods are recommended to confirm these findings and to explore any long-term effects of the suture materials and conduct similar studies in different animal models to ensure that these findings are not species-specific and to enhance the generalizability of the results.

Declarations

Ethics approval

Obtained from internal ethical committee.

Consent for publication

Obtained.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are included in this manuscript.

Competing Interests

"The authors declare that they have no competing interests" in this section.

Funding

None

Authors' contributions

Conceptualization: SS. Methodology: JH, VU, and AK; Formal investigation: AR, AC, and SG; Data analysis: SS, JH, VU, and AK; Writing original draft: SS; Writing - Review and editing: AR, AC, and SG.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Veterinarian, Anaesthesiologist, and Lab staff for the prompt assistance and high grade of professional competence that led to favourable outcome.

References

2. Breasted JH. The Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus: published in facsimile and hieroglyphic transliteration with translation and commentary in two volumes. 1930.

3. Dawson WR. Making a mummy. J Egypt Archaeol. 1927 Apr;13(1):40–9.

4. Greenberg JA, Clark RM. Advances in suture material for obstetric and gynecologic surgery. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Summer;2(3):146–58.

5. Leaper D, McBain AJ, Kramer A, Assadian O, Sanchez JL, Lumio J, et al. Healthcare associated infection: novel strategies and antimicrobial implants to prevent surgical site infection. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010 Sep;92(6):453–8.

6. Edmiston CE Jr, Daoud FC, Leaper D. Is there an evidence-based argument for embracing an antimicrobial (triclosan)-coated suture technology to reduce the risk for surgical-site infections?: A meta-analysis. Surgery. 2013 Jul;154(1):89–100.

7. Tomihata K, Suzuki M, Oka T, Ikada Y. A new resorbable monofilament suture. Polym Degrad Stab. 1998 Jan 3;59(1-3):13–8.

8. Williams DF. On the mechanisms of biocompatibility. Biomaterials. 2008 Jul 1;29(20):2941–53.

9. Ratner BD. The biocompatibility manifesto: biocompatibility for the twenty-first century. J Cardiovasc Transl Res. 2011 Oct;4(5):523–7.

10. Gourlay SJ, Rice RM, Hegyeli AF, Wade CW, Dillon JG, Jaffe H, et al. Biocompatibility testing of polymers: in vivo implantation studies. J Biomed Mater Res. 1978 Mar;12(2):219–32.

11. Hench LL, Polak JM. Third-generation biomedical materials. Science. 2002 Feb 8;295(5557):1014–7.

12. Fortes MA, Sadi MV. Estudo experimental comparativo com fios de sutura absorvíveis em bexiga de cäes. Rev Col Bras Cir. 1996:83–8.

13. Uff CR, Scott AD, Pockley AG, Phillips RK. Influence of soluble suture factors on in vitro macrophage function. Biomaterials. 1995 Jan 1;16(5):355–60.

14. Yaltirik M, Dedeoglu K, Bilgic B, Koray M, Ersev H, Issever H, et al. Comparison of four different suture materials in soft tissues of rats. Oral Dis. 2003 Nov;9(6):284–6.

15. Kakoei S, Baghaei F, Dabiri S, Parirokh M, Kakooei S. A comparative in vivo study of tissue reactions to four suturing materials. Iran Endod J. 2010 May 20;5(2):69.

16. Kim JS, Shin SI, Herr Y, Park JB, Kwon YH, Chung JH. Tissue reactions to suture materials in the oral mucosa of beagle dogs. J Periodontal Implant Sci. 2011 Aug 1;41(4):185–91.

17. Castelli WA, Nasjleti CF, Diaz-Perez R, Caffesse RG. Cheek mucosa response to silk, cotton, and nylon suture materials. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1978 Feb 1;45(2):186–9.

18. Do JH. Connective Tissue Graft Stabilization by Subperiosteal Sling Suture for Periodontal Plastic Surgery Using the VISTA Approach. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2019 Mar/Apr;39(2):253–8.

19. Lilly GE. Reaction of oral tissues to suture materials. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968 Jul;26(1):128–33.

20. Lilly GE, Armstrong JH, Salem JE, Cutcher JL. Reaction of oral tissues to suture materials. II. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1968 Oct;26(4):592–9.

21. Grigg TR, Liewehr FR, Patton WR, Buxton TB, McPherson JC. Effect of the wicking behavior of multifilament sutures. J Endod. 2004 Sep;30(9):649–52.

22. Ivanoff CJ, Widmark G. Nonresorbable versus resorbable sutures in oral implant surgery: a prospective clinical study. Clin Implant Dent Relat Res. 2001;3(1):57–60.

23. Parirokh M, Asgary S, Eghbal MJ, Stowe S, Kakoei S. A scanning electron microscope study of plaque accumulation on silk and PVDF suture materials in oral mucosa. Int Endod J. 2004 Nov;37(11):776–81.

24. Selvig KA, Biagiotti GR, Leknes KN, Wikesjö UM. Oral tissue reactions to suture materials. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1998 Oct;18(5):474–87.

25. Balamurugan R, Mohamed M, Pandey V, Katikaneni HK, Kumar KR. Clinical and histological comparison of polyglycolic acid suture with black silk suture after minor oral surgical procedure. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2012 Jul 1;13(4):521–7.

26. Urban E, King MW, Guidoin R, Laroche G, Marois Y, Martin L, et al. Why make monofilament sutures out of polyvinylidene fluoride? ASAIO J. 1994 Apr-Jun;40(2):145–56.

27. Sortino F, Lombardo C, Sciacca A. Silk and polyglycolic acid in oral surgery: a comparative study. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2008 Mar;105(3):e15–8.

28. Bond JL, Portell FR, Hartwell G. Custom models for endodontic surgery procedures. J Endod. 1986 Feb;12(2):82–4.

29. Pascal A, Frécon Valentin É. Liste des Résultats22. Extraite de : Moorhead S, Johnson M, Maas ML, Swanson E. Nursing outcomes Classification (NOC). St Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2008. 4e édition. – Taxonomie. Diagnostics Infirmiers, Interventions et Résultats: Elsevier; 2011. pp. 652–67.

30. Greenwald D, Shumway S, Albear P, Gottlieb L. Mechanical comparison of 10 suture materials before and after in vivo incubation. J Surg Res. 1994 Apr;56(4):372–7.

31. JAMES RC, MACLEOD CJ. Induction of staphylococcal infections in mice with small inocula introduced on sutures. Br J Exp Pathol. 1961 Jun;42(3):266–77.

32. Postlethwait RW. Five year study of tissue reaction to synthetic sutures. Ann Surg. 1979 Jul;190(1):54–7.

33. Zandim DL, Martins CO, Cavassim R, Rossa Júnior C, Abi-Rached RS, Sampaio JE. Morphological alterations on human radicular dentin after exposure to different fruit juice drinks. Revista Odonto Ciência. 2011;26:65–70.

34. Javed F, Al-Askar M, Almas K, Romanos GE, Al-Hezaimi K. Tissue reactions to various suture materials used in oral surgical interventions. ISRN Dent. 2012;2012:762095.

35. Ordman LJ, Gillman T. Studies in the healing of cutaneous wounds. I. The healing of incisions through the skin of pigs. Arch Surg. 1966 Dec;93(6):857–82.

36. Homsy CA, Fissette J, Watkins III WS, Williams HO, Freeman BS. Surgical suture–porcine subcuticular tissue interaction. J Biomed Mater Res. 1969 Jun;3(2):383–402.