Abstract

Cephalospinal fluid (CSF) dynamics (secretion and absorption) rate is considered a primary disturbance in the CSF dynamics. CSF reabsorption is a key part of ventriculomegaly, and to a lesser extent other anatomical features of CNS such as elasticity, brain water content, glial cell ratio, tissue atrophy, cranial suture status, age, weight, height, and sex.

Neonates and the elderly, the extremes of life, are more readily developed enlarged ventricles, supposedly in association with impairment of CSF absorption, but these absorption mechanisms are theoretical. The Evans index (EI), a linear ratio between the maximal frontal horn width and the cranium diameter, it is a relatively gross parameter that has been extensively used as an indirect marker of ventricular volume (VV).

The current accepted mechanisms of CSF secretion and reabsorption do not explain clinical observations, since they are based on theoretical processes such as ultrafiltration or third circulation theory as a means of production.

The unsuspected ability of human eukaryotic cells to transform the power of sunlight into chemical energy, through the dissociation of intracellularly located water molecules, makes it largely possible a paradigm shift with respect to the biodynamics of the Cephalospinal fluid.

Keywords

Aging, Brain ventricles, Cephalospinal fluid, Choroid plexus, Hydrogen, Oxygen, Water dissociation

Introduction

Brain structures—the intracranial volume (ICV) and ventricular volumes—vary significantly across individuals [1] even in the absence of neurological conditions [2].

Materials and Methods

The unsuspected existence of organic molecules inside eukaryotic cells that dissociate the water molecules present inside these cells, presupposes a paradigm shift in many ways in biology and therefore in medicine [3]. Given that many aspects of cell biology must be reconsidered, in the case of this work we will refer to tissues with the presence of fluids in an important way, such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and amniotic fluid.

Articles were searched in various sources of information such as PubMed and Google Scholar, whose content was pertinent to the topic to be discussed. And based on these articles, the following paragraphs were implemented.

Dynamic of CSF

Theoretically, most cerebrospinal fluids are produced in the lateral ventricles and drain out through the Sylvian aqueduct [4]. In the past decade, it was hypothesized that CSF is mainly produced from interstitial fluid excreted from the brain parenchyma, and CSF produced from the choroid plexus plays an important role in maintaining brain homeostasis. And CSF is not absorbed in the venous sinus via the arachnoid granules, but mainly in the dural lymphatic vessels. However, these mechanisms, like the previous ones, continue to be theoretical.

The choroid plexus (ChP), a highly vascularized (and pigmented) secretory structure in the brain’s ventricular system [5], plays key roles in immune function, maintaining the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier (BCSFB), and clearing metabolic waste. But the CSF does not come from the blood stream.

The BCSFB, formed by specialized ChP epithelial cells connected by tight junctions [6], regulates (theoretically) the exchange of substances between the blood and the CSF, protecting the brain from harmful substances [7]. Supposedly, Blood plasma that flows through the fenestrated capillaries is filtered into the ChP interstitium or stromal tissue, due (supposedly) to hydrostatic pressure [8]. The ultrafiltrates (produced by imaginary mechanisms), including ions, nutrients, and other molecules, along with newly secreted CSF, are actively transported into the ventricles. As well as ultrafiltration mechanisms are entirely theoretical, the way that “ultrafiltrates” molecules are “actively” transported, they have never been defined, much less proven.

CSF is predominantly secreted by the ChPs (by unknown mechanisms) in the lateral, 3rd, and 4th ventricles. After traversing the ventricular system and entering the subarachnoid space, CSF is absorbed into the bloodstream directly or via the lymphatic system [9]. This is contradictory, since the CNS, as well as the inside of the eye, lack lymphatic drainage.

The CSF production rate in humans is not clearly defined but is estimated to be 18–24 ml/h [10]. Supposedly, choroid plexus produces CSF at a rate of about 0.35 mL/min, which amounts to about 500 mL per day, and CSF is normally replaced about three to four times per day because the total intracranial CSF volume is estimated at about 150 mL, based on long-standing misconception [11].

A frequent clinical observation is that patients often drain higher volumes of CSF than could be explained by the assumed ‘normal’ CSF production rate (PRcsf), which from the point of view of pathophysiology is paradoxical and its explanation remains elusive [12].

CSF renewed approximately 3–5 times a day (like aqueous humor in the eye), maintaining a total CSF volume of 90–150 mls and a supine intracranial pressure (ICP) between 7 and 15 mmHg [13]. Absorption of CSF into the venous system seems to occur when CSF pressure is higher than the cerebral intravenous pressure, which is theoretical, so its dependence upon intracranial pressure [14] cannot be affirmed.

The conventional and entirely theoretical understanding of CSF production and circulation cannot explain that net CSF production rate is higher than expected in many conditions, for instance, in patients with cerebritis, ventriculitis, and micro abscesses, where the net average CSF production rate was found to be 77–106 ml/h [15].

Recent studies employing PC-MRI, radioactive water and biological dyes have challenged, as expected, the traditional and completely theoretical views of CSF hydrodynamics. A significant volume of CSF is formed by the choroid plexus (by water dissociation) and the remaining amount by the brain parenchyma, ependyma and the blood capillaries constituting the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [16]. It is (supposedly) absorbed by the arachnoid villi, as well as by the nasal lymphatics via the perineural spaces along the cribriform plate. Macromolecules and waste products are also removed along the intramural and perivascular pathways of the brain vasculature and probably by dural lymphatics. The exchange of CSF between the interstitial fluid and perivascular spaces is called the glymphatic system [17]. Because the dissociation of water molecules occurs primarily in the perinuclear space, and the reformation of liquid water can happen inside the melanosomes or outside them, but the dissociation of water occurs strictly inside the melanin molecule. Both processes are involved in both the production and reabsorption of CSF.

The word choroid means “like a chorion, membranous”, chorion refers to membrane enclosing the fetus, afterbirth; this is the outer membrane of the fetus. The word choroid dates to 1680 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A six-week-old embryo seen together with the chorion. The chorion, here opened, surrounds the embryo. The external surface of the chorion is characterized by many tiny projections, the chorionic villi, which establishes an intimate connection with the lining of the uterus (endometrium). The part of the chorion at left will give rise to the placenta (With permission of the authors [18]).

Chorion is a membrane that develops around the developing fertilized egg. It begins to develop during the early stages of pregnancy, particularly after the young embryo implants in the uterine lining (endometrium) and form the germ layers. The chorion’s main job is to protect and nourish the developing baby inside the mother’s womb. It also helps to create a barrier between the mother’s blood and the baby’s blood to prevent any harmful substances from passing through, like the blood brain barrier in the CNS. The fetal placenta is also referred to as the chorion frondosum.

The chorion is a thin, transparent membrane that surrounds the developing embryo. It is made up of several layers of cells, each with its own unique function (Figure 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Gross photograph of normal placenta. Notice the pigmentation. (With permission of the authors [19]).

Figure 3. The chorion is attached to the endometrium of the uterus, also forming the placenta. The oxygen levels inside the amniotic fluid are given by the dissociation of water that occurs inside the chorion cells. The pigment inside the cells´ fetus also dissociates water molecules, but it is for the benefit of the fetal cells. The dissociation of water molecules that occur in all cells in the region (and the entire body) is a determining factor in both the levels of dissolved oxygen in the amniotic fluid, as well as the constant regulation of pH. (Photograph with permission of the authors).

The structure of the chorion is crucial for supporting the growing fetus by providing it with nutrients, oxygen, and protection from harmful substances. The chorion is one of the first membranes that form during a pregnancy and is composed of two layers, the mesoderm and trophoblasts. Its grade of pigmentation is variable.

The trophoblast is composed of two layers — the outer syncytiotrophoblast, which is a multinucleated layer of fused cells, and the inner cytotrophoblast, which consists of individual cells. These two layers work together to create a barrier between maternal and fetal blood circulation and facilitate the exchange of nutrients, gases (if any, at most small quantities of CO2), and waste products. (Figure 4).

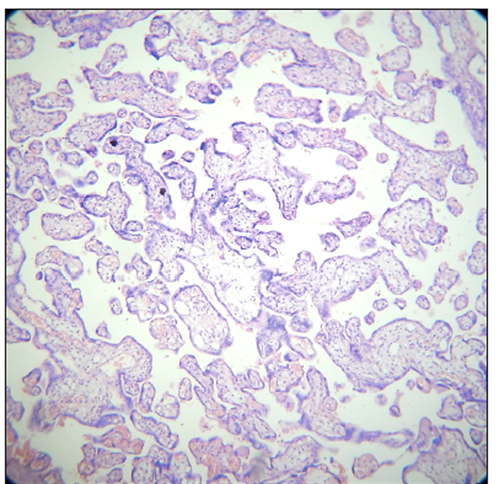

Figure 4. Normal term placenta, H & E, X 100 (With permission of the authors [17]).

Our work on the idea that human cells produce their own oxygen from the dissociation of intracellular water [20], has resulted in the finding that the perinuclear space, the region where the dissociation and reforming of water mainly occurs, constitutes a negative pressure zone that attracts liquids from the immediate environment, so that each nucleus that is stained with hematoxylin can be thought of as a mini suction pump.

Choroid plexus (Figure 5)

The choroid plexuses are villus structures occurring in each of the four major ventricular cisternae. They are the main site of elaboration of cerebral spinal fluid (by water dissociation). They all share a similar microscopic appearance comprising a single layer of cuboidal epithelium overlying capillary loops which are embedded in a scanty connective tissue stroma. The surface area of the epithelial surface is greatly enlarged by basolateral infoldings and surface microvilli. Monocytic cells or macrophages and dendritic cells are present in the stroma. The fine structure of the epithelial cells, notably a large number of mitochondria, like the photoreceptor cells (rods and cones) in retina. Passive solute exchange between blood and CSF is highly restricted by tight junctions that seal the epithelium at the apical cerebral spinal fluid-facing poles of the cells. Blood-borne molecules such as horseradish peroxidase have been shown to pass through the fenestrated choroidal capillaries (as in the choroid of the eye) into the stromal space and into the lateral intercellular spaces between the basal halves of the epithelium but not through the apical tight junctions.

Figure 5. The choroidal plexuses (V) contain significant amounts of melanin. In this specimen, M indicates the presence of a meningioma (With permission of the authors [21]).

The fact that water dissociates and reforms inside choroidal cells opens the possibility that the same structure that produces cerebrospinal fluid is also capable of reabsorbing it.

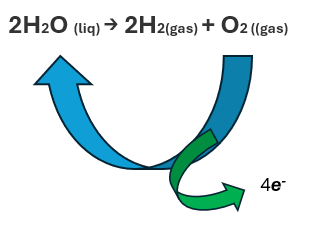

The water dissociation and reforming reaction that occurs primarily in the perinuclear space can be written as follows:

2H2O (liq) → 2H2 (gas) + O2 (gas) → 2H2O (liq) + 4e-

The part highlighted in green occurs strictly inside the melanosomes, the part highlighted in blue occurs inside and outside them.

So, the transformation of the power of sunlight (visible and invisible), into chemical energy through water dissociation, is the fundamental role of melanin in any living thing. Besides skin, and hair, in vertebrates, melanin is present in various organs and tissues such as spleen, liver, kidney, brain, pineal gland, inner ear, eye (Figures 6–9), lung, connective tissues, testis, choroid, heart, peritoneum, muscles, venom glands and tumors [22].

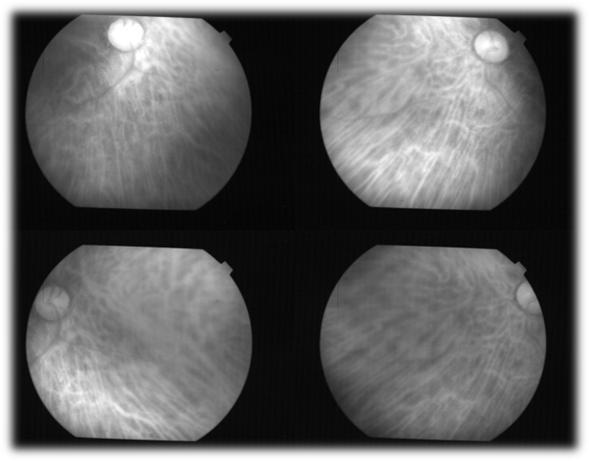

Figure 6. The image shows the optic nerve and retina of the left eye. Retinal blood vessels are sparse, and they all exit and enter through the optic nerve. This vasculature handles only 2% of the blood that leaves the first intracranial branch of the internal carotid artery (Herrera AS, et al., 2025, ©).

Figure 7. The choroid in humans is only visualized in the living patient, using wavelengths greater than 750 nanometers, which allows us to observe the large number of fenestrated capillaries that make it up, as well as in the choroidal plexus of the ventricles of the brain. In humans, the choroid handles 98% of the blood that enters the eyeball (Herrera AS, et al., 2025, ©).

Figure 8. In this histological section of the human retina, the photoreceptors are observed on the right of the photograph. The layer of axis-cylinder (axons) from the ganglion cells is seen on the left (Herrera AS, et al., 2025, ©).

Figure 9. Histological section of the human choroid, where the important presence of melanin is appreciated, in the pigmented epithelium of the retina (left), and in the choroid itself on the right. The function of melanin is to transform the power of light into chemical energy, by dissociating water (Herrera AS, et al., 2025, ©).

Figure 10. Dissociation reaction of water (Herrera AS, et al., 2025, ©).

The dissociation reaction of water is exact, amazingly exact, and very constant, incessant. The reaction happens in the order of nano (1 x 10 -9 seconds) and pico (1 x 10 -12) seconds.

Due to its characteristics, it can be considered the very first reaction of life, and melanin, wherever it is found, has the same function. Apparently, the function of water dissociation is taken to its maximum when the anatomy resembles the choroid of the eye, the choroid plexus of the ventricles, and the chorion of the embryo or fetus.

In various mammals, melanin pigments (not neuromelanin but other compounds with the same function) are also present in the pineal gland, a small endocrine gland of the brain producing melatonin, a hormone regulating seasonal reproductive function and modulating circadian rhythms. Indeed, in the big brown bat (Eptesicus fuscus), the melanin content of this gland increases during hibernation and prolonged darkness [23].

Ageing

The concentration of neuromelanin decreases as pigmented neurons are selectively lost, whereas nonpigmented neurons are generally spared during the progression of the disease [24]. Therefore, the level of neuromelanin is lower in humans with Parkinson's disease than in healthy people. In addition, the mean area of the substantia nigra occupied by neuromelanin is in average, lower in humans with the neurodegenerative Alzheimer's disease compared to healthy people [25].

Our body begins to lose gradually its capacity to dissociate the water molecules at 26 years old, approximately 10% each decade, and after 50s goes into free fall.

The generation of oxygen and hydrogen at the intracellular level explains, in a congruent way, the beginning of the innumerable chemical reactions that make up or that we call life. And the decrease in neuromelanin, of course, is followed by a decrease in the functions of the affected tissue, which can reach a point where even the mass tends to disappear, even irregularly, as happens in the brains of Alzheimer's patients.

Current studies on CNS do not detect a process as subtle and rapid as the dissociation of water, which occurs inside neurons, and strictly inside melanin molecules.

The BBB has been studied intensively, and with the Evans blue, that is a dye that binds to plasma albumin, the function of such a barrier is demonstrated quite well. When injected intravenously, all the macrophages in the body are taken up except those that lie beyond a blood-tissue barrier. At autopsy, the blue body of the rat or rabbit contrasts sharply with the bright white color of the brain and nerves [26].

In the CNS ischemia tends to develop as secondary effect because nervous tissue is tightly packed (it has almost no extracellular spaces), it has not drainage lymphatic (like the eye), and being locked inside a box of bone, it cannot swell or expand to accommodate the exudate. Nervous tissue is especially sensitive to free radical damage because myelin is rich in lipids, which are the favorite target of free radicals (lipoperoxidation). The blood-tissue barrier most studied is the brain [27].

The gradual and progressive loss of the human body's ability to dissociate water molecules is reflected in the gradual loss of our body's functions and capabilities, and eventually mass tends to disappear. That is the reason why in adults, total CSF volume measures approximately 150 ml, about 125 ml within the subarachnoid spaces and 25 ml within the ventricles. However, older individuals may have volumes approaching 350 ml due to cerebral atrophy [28] secondary to the gradual loss of the hitherto unknown of the cells that make up the CNS, to transform the power of sunlight into chemical energy that can be used by eukaryotic cells, through a mechanism that could be considered universal: the dissociation of water molecules.

Discussion

Until now, the functions of biological pigments were considered somewhat superficial, as they selectively absorb one wavelength and reflect the others. In medicine, they were considered mainly simple sunscreen to protect against UV irradiation. They also helped identify the sex of animals, communication between them, etc.

But pigments were not conceived to have a role that even encompasses the origin of life. But their unsuspected ability to dissociate water molecules located intracellularly presuppose a before and after in biology and medicine, since it turns out that they constantly provide the hydrogen and oxygen that each cell constantly requires, throughout life.

Conclusion

As the dogma that the oxygen required by our body comes from the atmosphere finally disappears, and therefore the unsuspected ability of human cells to oxygenate themselves gains wide acceptance, then we will be able to advance in the study of human biology and physiology, understanding in a more efficient way the processes that are observed around life. Such as aging, for example.

Acknowledgement

This work was possible thanks to the generous support of Human Photosynthesis™ Research Center. Aguascalientes 20000, México.

Conflict of Interest

None.

References

2. Vojinovic D, Adams HH, Jian X, Yang Q, Smith AV, Bis JC, et al. Genome-wide association study of 23,500 individuals identifies 7 loci associated with brain ventricular volume. Nat Commun. 2018 Sep 26;9(1):3945.

3. Herrera AS. The biological pigments in plants physiology. Agricultural sciences. 2015 Oct 12;6(10):1262–71.

4. Spector R, Robert Snodgrass S, Johanson CE. A balanced view of the cerebrospinal fluid composition and functions: Focus on adult humans. Exp Neurol. 2015 Nov;273:57–68.

5. Hutton D, Fadelalla MG, Kanodia AK, Hossain-Ibrahim K. Choroid plexus and CSF: an updated review. Br J Neurosurg. 2022 Jun;36(3):307–15.

6. Lun MP, Monuki ES, Lehtinen MK. Development and functions of the choroid plexus-cerebrospinal fluid system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2015 Aug;16(8):445–57.

7. Liddelow SA, Dziegielewska KM, Vandeberg JL, Saunders NR. Development of the lateral ventricular choroid plexus in a marsupial, Monodelphis domestica. Cerebrospinal Fluid Res. 2010 Oct 5;7:16.

8. Orešković D, Radoš M, Klarica M. Role of choroid plexus in cerebrospinal fluid hydrodynamics. Neuroscience. 2017 Jun 23;354:69–87.

9. Sakka L, Coll G, Chazal J. Anatomy and physiology of cerebrospinal fluid. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2011 Dec;128(6):309–16.

10. Trevisi G, Frassanito P, Di Rocco C. Idiopathic cerebrospinal fluid overproduction: case-based review of the pathophysiological mechanism implied in the cerebrospinal fluid production. Croat Med J. 2014 Aug 28;55(4):377–87.

11. McComb JG. Recent research into the nature of cerebrospinal fluid formation and absorption. Journal of neurosurgery. 1983 Sep 1;59(3):369–83.

12. Tully B, Ventikos Y. Cerebral water transport using multiple-network poroelastic theory: application to normal pressure hydrocephalus. Journal of fluid mechanics. 2011 Jan;667:188–215.

13. Chau CYC, Craven CL, Rubiano AM, Adams H, Tülü S, Czosnyka M, et al. The Evolution of the Role of External Ventricular Drainage in Traumatic Brain Injury. J Clin Med. 2019 Sep 10;8(9):1422.

14. Brinker T, Stopa E, Morrison J, Klinge P. A new look at cerebrospinal fluid circulation. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2014 May 1;11:10.

15. Tariq K, Toma A, Khawari S, Amarouche M, Elborady MA, Thorne L, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid production rate in various pathological conditions: a preliminary study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2023 Aug;165(8):2309–19.

16. Brinker T, Stopa E, Morrison J, Klinge P. A new look at cerebrospinal fluid circulation. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2014 May 1;11:10

17. Hladky SB, Barrand MA. Mechanisms of fluid movement into, through and out of the brain: evaluation of the evidence. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2014 Dec 2;11(1):26.

18. PROFESSORS P.M. MOTTA & S. MAKABE / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY.

19. Mondal TR, Bandyopadhyay G, Mukhopadhyay SG, Ganguly D. Histopathological Changes of Placenta in Meconium Stained Liquor and Its Relevance in Fetal Distress: A Case Control Study. Turk Patoloji Derg. 2019;35(2):107–18.

20. Herrera AS, Esparza MD. The unsuspected ability of the human cell to oxygenate itself. Applications in cell biology. Medical Research Archives. 2025 Mar 29;13(3).

21. Photograph: Dr. T. W Smith. University of Massachusetts Medical Center, Worcester. MA. USA.

22. Rózanowska M. Properties and functions of ocular melanins and melanosomes. In: Borovansky J, Riley PA, Editors. Melanins and Melanosomes; Biosynthesis, Biogenesis, Physiological and Pathological Functions. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co.); 2011. pp. 187–224.

23. Reppert SM, Weaver DR, Ebisawa T. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian melatonin receptor that mediates reproductive and circadian responses. Neuron. 1994 Nov;13(5):1177–85.

24. Fedorow H, Tribl F, Halliday G, Gerlach M, Riederer P, Double KL. Neuromelanin in human dopamine neurons: comparison with peripheral melanins and relevance to Parkinson's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2005 Feb;75(2):109–24.

25. Reyes MG, Faraldi F, Rydman R, Wang CC. Decreased nigral neuromelanin in Alzheimer's disease. Neurol Res. 2003 Mar;25(2):179–82.

26. Hunsaker WG. Determination of Evans blue in avian plasma by protein precipitation and extraction. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1965 Dec;120(3):747–9.

27. Juhler M, Neuwelt EA. The blood-brain barrier and the immune system. In: Neuwelt EA, Editor. Implications of the Blood-Brain Barrier and Its Manipulation: Volume 1 Basic Science Aspects. New York: Springer New York; 1989. pp. 261–92.

28. Yamada S, Mase M. Cerebrospinal Fluid Production and Absorption and Ventricular Enlargement Mechanisms in Hydrocephalus. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 2023 Apr 15;63(4):141–51.