Abstract

Background: Hiatal hernia is not an uncommon condition; however, a large hernia producing symptoms that mimic an acute cardiac condition is extremely uncommon. This clinical case report highlights unusual presentation of hiatal hernia where early recognition and timely intervention were key to ensure favorable patient outcome.

Case summary: We report the case of a 52 years old gentleman with a history of ABO-incompatible living donor liver transplant for hepatitis B related hepatocellular carcinoma, who presented with acute pericarditis like chest pain. Physical examination was unremarkable apart from moderate distress due chest pain. His 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a new left bundle branch block (LBBB) with secondary repolarization abnormalities. High sensitivity Troponin-T was serially normal. The total white blood cell count was mildly elevated with normal C reactive protein. A plain chest radiograph showed gas-filled bowel loops in left hemithorax. Further evaluation with computed tomography (CT) showed a 4-5cm left diaphragmatic defect with bowel loops herniating into the left mediastinum. The hernia was surgically corrected. The patient's symptoms and LBBB resolved completely during follow up.

Conclusions: This case presents a mysterious association between a giant hiatal hernia and LBBB and highlights the importance of a broad diagnostic approach in achieving the correct diagnosis.

Keywords

Chest pain, Hiatal hernia, Pericarditis, Case reports, Left bundle branch block

Introduction

Hiatal hernia is not an uncommon condition. Due to inconsistent definition in the literature, the reported prevalence varies widely between 15- 50%. The condition is symptomatic in only 9% of the cases, especially with advancing age [1]. Cardiac evaluation is frequently obtained in those patients because the symptoms can mimic cardiac ischemic or inflammatory chest pain. These patients tend to be older and on treatment for one or more vascular risk factors. Overall, the index of suspicion for a diaphragmatic hernia tends to be low, given rarity of the condition in clinical practice. Large Hiatal hernias are infrequent, but they can lead to atypical symptoms such as chest pain, dyspnea due to a compressive effect on the heart or pulmonary veins. Sui CW and colleagues reported on a large hiatal hernia that compressed the left atrium in a patient presenting with recurrent acute heart failure [2]. Hiatal hernias can also present with severe chest pain mimicking acute coronary syndromes [3].

Case Report

A 52-year-old male patient was admitted under the gastroenterology unit at the Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH) with chest pain, nausea, and vomiting. This patient had undergone an ABO-incompatible live donor liver transplantation abroad in 2015 for an advanced hepatocellular carcinoma complicating chronic hepatitis B virus infection related hepatic cirrhosis. He was maintained on tacrolimus and received multiple courses of systemic steroids for recurrent acute cellular rejection. He also had bronchiectasis. The described pain was central, pleuritic in nature, aggravated by lying flat and relieved by leaning forwards and walking, the pain had been unrelenting for three continuous days before seeking medical attention. Given his age, the treating physicians requested an urgent cardiac evaluation to rule out ischemic or inflammatory cardiac etiologies for the pain.

On examination, the patient was in moderate pain with otherwise normal vital parameters and cardiovascular examination. The initial 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) showed Left Bundle Branch Block with secondary repolarization abnormalities making further interpretation for ischemic or inflammatory changes challenging (Figure 1). Of interest, this was a new finding when compared to previous electrocardiograms. His chest x-ray showed a gas-filled bowel loop in the left hemithorax (Figure 2). The patient’s initial hematological and biochemical panels including serial high sensitivity Troponin-T assays were unremarkable apart from white blood cell (WBC) count of 16,000/mm3 (normal reference range 4,000-10,000/mm3). C-reactive protein level was within the normal reference range.

Due to the patient’s immune-compromised status, cytomegaly virus (CMV) serology, and autoimmune workup were sent by the parent team to investigate for possible relevant causes for pericarditis. CMV serology result was weakly reactive for both IgM and IgG antibodies. In the context of the patient's background, acute presentation of serositis chest pain, non-conclusive ECG, normal troponin, and positive CMV serology acute pericarditis was considered a reasonable working diagnosis. Therefore, Transthoracic echocardiography was urgently arranged to look for supporting features for pericarditis. Meanwhile, the gastroenterology team arranged esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), which surprisingly showed gastric torsion at the level of the upper gastric body and strongly noticeable cardiac pulsation at the fundus.

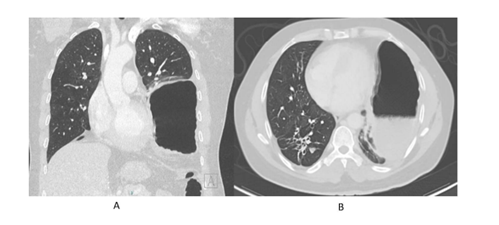

CMV PCR was negative and the echocardiographic study showed normal left ventricular systolic function and resting wall motion with no pericardial effusion. Due to the EGD findings decision was made by the primary team to carry on with Computed tomographic (CT) examination of the thorax and abdomen along with an urgent surgical consultation. CT showed an approximately 4-5 cm wide defect within the posterior-central part of the left hemidiaphragm with an incarcerated herniation of fundal part of the stomach (Figure 3).

Patient was posted for exploratory laparotomy for hiatal hernia repair. Stomach was reduced and diaphragmatic defect closed successfully. Post-surgery, patient had uneventful recovery, his previous concerning symptoms resolved completely, and he was discharged to follow up with his primary gastroenterologist. A follow up ECG done (Figure 1c) 2 months after the surgery unexpectedly showed resolution of the left bundle branch block seen on the admission ECG.

Figure 1: A: One year prior to presentation showing no evidence of LBBB; B: At presentation, an Electrocardiography showing sinus rhythm with left bundle branch block with secondary repolarization abnormalities. C: Two months post-surgical repair showing resolution of LBBB pattern.

Figure 2: A: One-year prior presentation. B: At presentation, x-ray showing a gas-filled bowel loop in the left mediastinum passing through the left hemidiaphragm. C: Post-surgical repair.

Figure 3: A: Axial thorax CT (lung window) demonstrates air filled structure occupying Left hemi thorax with fluid density seen posteriorly representing the stomach. B: Coronal thorax CT (lung window) redemonstrates stomach in the left lower hemithorax displacing the lung lower lobe.

Discussion

In the case discussed, a large hiatal hernia produced pericarditic chest pain, which worsened with a recumbent position and deep inspiration and diminished in an upright posture. It is conceivable that laying down encouraged further stomach herniation and the negative intrathoracic pressure generated by inspiration resulted in an interval increase in hernia size further aggravating the pain. The pericarditic nature of the pain would have been due to a direct irritant effect from the incarcerated and inflamed bowel loops against the adjacent serosa, be it pericardium or pleura. Evidently, and once the primary pathology was surgically reduced, the presenting complaint resolved. A hiatal hernia presenting with pericarditis with classical ST-segment elevation on the standard ECG has also been described [4].

The presenting ECG demonstrated a new left bundle branch block (LBBB), which might have masked the typical ECG changes expected with acute pericarditis (Figure 1A). Acute ischemia as a cause of the LBBB was also effectively ruled out with negative serial c-Tn-T assays and a normal left ventricular systolic function and wall motion combined with the non-ischemic chest pain history. Interestingly, conduction abnormality strongly correlated with the presence of his hernia (Figures 2A-2C). This finding resolved on the postoperative ECG. Although many cases reported LBBB and ST segment elevation in patients with hiatal hernia , LBBB was not previously noted to be a such dynamic finding, which normalized after hernia repair [4-8].

The exact cause of the various ECG changes described in the literature remains elusive. One of the theories postulated include a direct compressive effect on the epicardial surface [4]. Dramatic depolarization and repolarization abnormalities have been described even in the absence of obstructive coronary lesions [9]. Left bundle branch block could be the result of dys-synchronous left ventricular contraction due to displacement of the heart and compression by the large hernia. Rate-related LBBB is unlikely in our patient, since the finding was documented at rates that previously coincided with a narrow QRS complex. Extrinsic compression of the epicardial coronary vessels resulting in ischemic LBBB is also a plausible explanation. However, the serially normal c-Tn-T assays, normal left ventricular wall motion on echocardiography and the non-ischemic chest pain in a middle-aged man with no documented atherogenic risk factors, effectively rules out that possibility. Whatever may be the mechanism and judging by the resolution of the conduction abnormality on the follow up ECG, we conclude that the findings were directly related to the large, compressive hiatal hernia.

Conclusion

In summary, large hiatal hernia should be on the list of rare differential diagnoses for acute coronary syndromes. The abnormality not only presents with chest pain but with variable ECG abnormalities, including new and dynamic LBBB which is reported for the first time with our case. physicians should have a high index of suspicion in the appropriate clinical settings, especially in patients with previous complex abdominal surgeries. This will aid in early detection and timely management averting potentially life-threatening complications as shown in our case.

Conflict of Interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

2. Siu CW, Jim MH, Ho HH, Chu F, Chan HW, Lau CP, et al. Recurrent acute heart failure caused by sliding hiatus hernia. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2005 Apr 1;81(954):268-9.

3. Chau AM, Ma RW, Gold DM. Massive hiatus hernia presenting as acute chest pain. Internal Medicine Journal. 2011 Sep;41(9):704-5.

4. Hokamaki J, Kawano H, Miyamoto S, Sugiyama S, Fukushima R, Sakamoto T, et al. Dynamic electrocardiographic changes due to cardiac compression by a giant hiatal hernia. Internal Medicine. 2005;44(2):136-40.

5. Schummer W. Hiatal hernia mimicking heart problems. Case Reports. 2017 Jul 27;2017:bcr-2017.

6. Holý J, Červinka P, Omran N, Koscelanský J. “Acute coronary syndrome” and heart failure caused by a large hiatal hernia. Cor et Vasa. 2018 Oct 1;60(5):e522-6.

7. Elterman KG, Mallampati SR, Tedrow UB, Urman RD. Postoperative episodic left bundle branch block. A&A Practice. 2014 Feb 15;2(4):44-7.

8. Rubini Gimenez M, Gonzalez Jurka L, Zellweger MJ, Haaf P. A case report of a giant hiatal hernia mimicking an ST-elevation myocardial infarction. European Heart Journal-Case Reports. 2019 Sep;3(3):ytz138.

9. Sonoda K, Ikeda S, Seki M, Koga S, Futagawa K, Yoshitake T, et al. Chest pain and ST segment depression caused by expansion of gastric tube used for esophageal reconstruction. Internal Medicine. 2005;44(3):217-21.