Abstract

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are one of the leading causes of mortality in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA); however, access to sustainable cardiac care remains limited. The reliance on short-term medical mission-based interventions has not addressed the critical workforce and infrastructure gaps in the region. The Global Heartcare Foundation (GHF) provides a framework for transitioning from episodic care to locally driven team-based solutions. Through comprehensive training programs, high-volume cardiac center partnerships, strategic investments, and locally led research, the GHF has enabled the development of independent cardiac teams and infrastructure in Ethiopia and Tanzania. To date, GHF has trained more than 50 African physicians, nurses, and technicians, and supports national registries for Rheumatic and Congenital Heart Disease alongside expanding digital learning initiatives. This review offers a framework for building sustainable cardiovascular care systems in low-resource settings, emphasizing team training, partnerships, mentoring, infrastructure investments, and long-term capacity building.

Keywords

Cardiac team training, sub-Saharan Africa, Global cardiovascular health, Workforce development, Sustainability

Abbreviations

SSA: Sub-Saharan Africa; CVD: Cardiovascular Disease; RHD: Rheumatic Heart Disease; GHF: Global Heartcare Foundation; NICS: Narayana Institute of Cardiac Sciences; KCMC: Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center; NGOs: Non-Governmental Agencies

Introduction

For decades, global health initiatives in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) have prioritized combating communicable diseases such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria. While these efforts have led to significant progress and reductions in the mortality associated with these conditions, the region now faces an evolving healthcare landscape marked by the convergence of infectious and chronic diseases. Between 2000 and 2019, deaths from noncommunicable diseases surged from 24% to 37%, signaling a shift that demands urgent attention [1]. According to the 2021 Africa Health Agenda International Conference, fewer than half of Africa's population had access to basic healthcare due to a severe shortage of health workers [2]. There are only 1.5 health workers per 1,000 individuals, which is significantly below the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals of 4.45 per 1,000 [3,4]. Furthermore, estimates indicate that cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) account for roughly 13% of all deaths in SSA and by 2030, noncommunicable diseases are projected to surpass communicable as the region’s leading causes of mortality with CVDs comprising the largest share of noncommunicable related deaths at approximately 38% [5,6]. While ischemic heart disease, hypertension and stroke remain the predominant cause of CVD-related deaths, other conditions such as rheumatic heart disease (RHD), congenital heart disease, and cardiomyopathies pose substantial short and long-term risks of morbidity and mortality [7].

The burden of CVDs is further exacerbated by a shortage of trained professionals and infrastructure. This disparity comes into sharper focus as specialized areas of medicine are examined. Recent estimates suggest that Africa has only 2,000 practicing cardiologists and just 22 dedicated cardiothoracic centers [8]. In addition, the continent represents 10% of the global population yet carries approximately 25% of the world’s disease burden with only 4% of the global health workforce [9]. While medical missions are well-intentioned and can provide lifesaving surgeries or interventions for individual patients, they do little to address the broader systemic issue, the shortage of trained cardiac professionals. Participation by local staff often varies depending on the visiting mission partners, leading to inconsistent training experiences [10]. Additionally, these trips are typically episodic, resourceintensive, and lack the structural continuity necessary for long-term impact and sustained care. As a result, cardiac training programs in SSA remain critically under-resourced, offering limited training capacity relative to the escalating burden of disease [11]. These patterns underscore the urgent need to invest in sustainable healthcare solutions tailored to the region’s unique challenges. Moving forward, efforts must be directed toward tangible actions rather than relying on intermittent external support.

The Global Heartcare Foundation (GHF), a USA-based 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization, is committed to transforming urgency into an impact. The mission of the GHF is to improve the health of patients with CVDs in developing countries across Africa and Asia through lifesaving treatments, medical training, research, and the development of sustainable cardiac programs. Founded by a cardiothoracic surgeon with over 25 years of experience in voluntary cardiac care, GHF is dedicated to building long-term, locally anchored solutions. This model builds a cardiac team with selected partnerships for comprehensive training, mentoring, advocacy, strategic investments in resources, and research suitable for low- and middle-income countries (Figure 1).

Figure1. Transforming cardiac care in sub-Saharan Africa: a sustainable approach.

Cardiac Teams

The core pillar of our approach is the selection, funding, and deployment of comprehensive cardiac care teams for specialized training. Building a trained cardiac team is essential to delivering high-quality care and improving patient outcomes. These teams should include adult and pediatric cardiologists, interventional cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, cardiac anesthesiologists, critical care specialists, cardiac perfusionists, nurses, and technicians. While some cardiac centers across SSA have personnel in place, critical gaps persist in key subspecialties. The piecemeal approach to training has had limited success in addressing SSA’s unique healthcare challenges.

Our approach addresses this gap by promoting a holistic framework that enables multidisciplinary teams to train and operate simultaneously. Teams were deployed to the Narayana Institute of Cardiac Sciences, Narayana Health (NICS), one of the world’s leading cardiac centers in India, for specialized training across various cardiac disciplines. The NICS pioneered a model that delivers high-quality care at a lower cost. Trainees can learn about resource utilization and be equipped to apply this knowledge in their home countries. To date, this high-volume center has successfully trained over 130 African physicians [12].

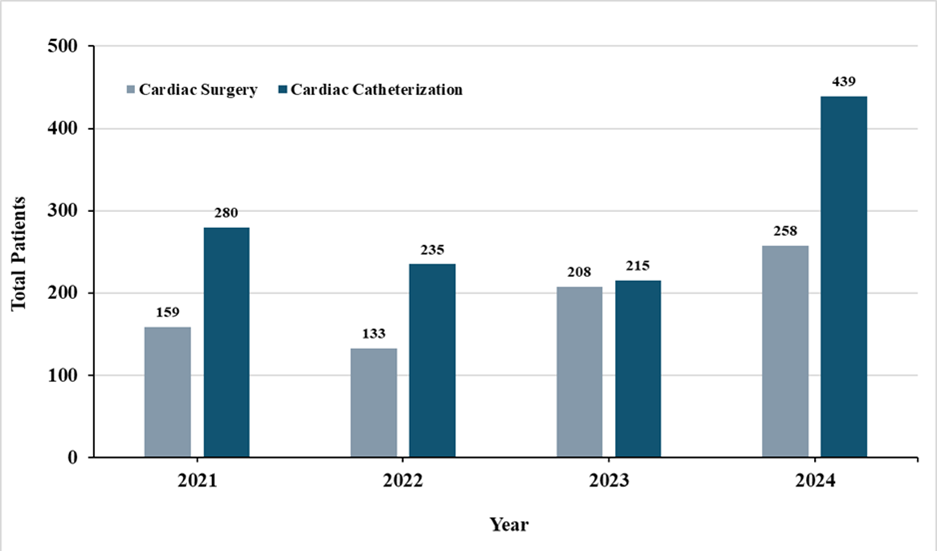

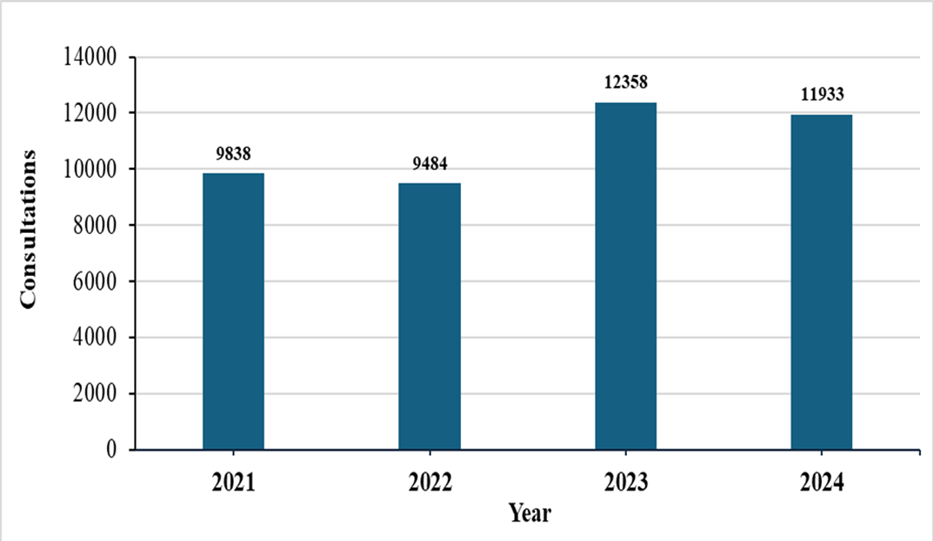

In 2010, we collaborated with the Cardiac Center and Children’s Heart Fund of Ethiopia in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. At that time, there were no trained cardiac teams to serve a population of over 120 million, and the center initially relied on visiting mission teams. Our first initiative began with cardiac surgery missions at the Cardiac Center. Subsequently, with our support, a 12-member cardiac team comprising adult and pediatric cardiologists, interventionalists, surgeons, anesthesiologists, perfusionists, and critical care nurses were successfully trained at the NICS, leading to the establishment of a unified model of care. By 2017, the team began to operate independently. Currently, the center provides training rotations for Ethiopian trainee cardiac surgeons, cardiologists, and perfusionists. Notably, the COVID19 pandemic impacted delivery of heart care internationally, including Ethiopia with global data showing a 40 to 60% decline in cardiovascular diagnostic testing during the early months of the pandemic [13]. However, following the COVID-19 pandemic, Ethiopian teams surgical and cardiac catheterization laboratory interventions gradually increased (Figure 2). The number of outpatient cardiology consultations has also increased to more than 11,000 annually (Figure 3). The increased exposure in treating more complex cases has translated to improved patient outcomes, overall ICU mortality has decreased from 2% to current levels of 0.8%. These successes reinforce a broader imperative not only to train local professionals, but also to retain them. Despite ongoing efforts, a 2023 literature analysis found physician “brain drain” remains an ongoing challenge across Africa, driven by poor working conditions, limited career advancement, low living standards, and sociopolitical instability [14]. By creating pathways for career advancement, we aim to foster professional fulfillment at home. Efforts such as mentorship, leadership opportunities, and access to digital learning tools contribute to workforce sustainability and community-centered care.

Figure 2. Number of cardiac surgeries and cardiac catheterization procedures from 2021 to 2024.

Figure 3. Number of outpatient cardiology consultations from 2021 to 2024.

Similarly, our partnership with Kilimanjaro Christian Medical Center (KCMC) in Moshi, Tanzania, currently supports a team of seven physicians in cardiology, cardiac surgery, cardiac anesthesiology, and critical care. In addition, seven critical care nurse specialists completed the training. These efforts reflect our broader philosophy that cardiac care teams in SSA should mirror cohort-based models using international standards of professional competency, knowledge, and quality of care.

RHD remains one of the most prevalent and under-addressed cardiovascular conditions in SSA, particularly in children and young adults with central SSA carrying the thirdhighest burden of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) globally [15]. Management of advanced cardiac disease often necessitates interventional or surgical procedures requiring highly specialized skills, yet many regions lack the infrastructure, expertise, and procedural volume needed to support training in these techniques [16]. To bridge this gap, our model facilitates training in high-volume centers in India, including the NICS, where physicians are exposed to congenital and heart valve surgery cases and advanced interventions. By equipping teams with procedural proficiency to address RHD locally, preventable morbidity and mortality can be significantly reduced while building specialized cardiac expertise within the region.

Partnerships

Strategic partnerships are a central pillar of our approach, encompassing multiple areas of focus in assessing the critical gaps in a particular center’s ability to improve cardiac care. From formal training and e-learning to infrastructure development and financial investment, these efforts foster workforce expertise and drive effective resource allocation. We partner with governmental agencies, nonprofit organizations, local healthcare facilities, and, most importantly, high-volume cardiac centers for training. These centers are essential as they expose trainees to a wide array of surgical and medical cases. Although Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) play a vital role in bridging this gap in cardiac surgery, their impact remains poorly understood. In a recent report, 86 cardiac surgery NGOs working in 96 low-to middle-income countries, with most performing less than 50 surgeries each year, had limited transparency in outcome reporting [17]. This highlights the importance of developing scalable and long-term models focused on capacity building and local autonomy; the exact priorities that shape our partnership-based approach.

Our collaboration with the NICS has strengthened the support for developing cardiac training programs for African teams. In 2020, our partnership efforts expanded to Tanzania, where our relationship with KCMC, a teaching hospital affiliated with a local university, became a key part of this growth. In collaboration with other NGOs, a new cardiac center is under development. Upon completion, cardiac care will be provided to over 15 million people in northern Tanzania. While some cardiac programs may have surgical capacity, many face a critical shortage of cardiac perfusionists, limiting their ability to increase surgical volume. One such program was identified in Uganda, where a perfusionist is currently undergoing training at the NICS.

Access to education is also expanding through digital platforms. Web-based learning is a vital tool for professional development in geographically isolated regions. In partnership with NICS, we launched a virtual seminar series on echocardiography and critical care to enhance access to high-quality training. E-learning modules are offered as part of perioperative and critical care cardiology training, specifically for transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography. Similarly, weekly online tutorials provide opportunities for participants, especially those from developing countries, to enhance their knowledge and engage in comprehensive exit examinations to assess their learning progress. Based on this success, we are developing The Global Virtual Heartcare University, a comprehensive online platform that offers educational events across all areas of cardiac care. These initiatives aim to bridge geographical and resource-based gaps, ensuring ongoing skill development.

Investments in Infrastructure and Equipment

Investing in appropriate infrastructure and equipment anchors our model’s long-term sustainability. Internal healthcare investment across SSA has remained stagnant, with many countries allocating around 7% of their national budgets to healthcare, which is below the 15% target set by the Abuja Declaration [18]. As a result, numerous cardiac programs operate without the basic physical or technical infrastructure required to deliver safe and consistent care. For most NGOs, building such infrastructure independently is financially and logistically unfeasible. Although NGOs can play a role in workforce development and program implementation, the heavy capital investments required for hospitals, operating rooms, and high-tech equipment often exceed the scope of their mission or financial capacity. Moreover, the high cost of single-use or disposable cardiac consumables poses a significant constraint on the expansion of cardiac services in low-to middle-income countries. This underscores the critical role of the private sector, including medical device manufacturers and global health investors, in collaboratively advancing sustainable cardiac care. With appropriate financing models, regulatory support, and partnership incentives, medical device companies have significant opportunities to expand into SSA markets as future investment frontiers in device use and sales. By adapting products to local markets and supporting their use, these companies can bridge the gap between a short-term mission and self-sufficient cardiac care ecosystems.

Research

As the final pillar of our model, locally led research provides the foundation for building sustainable evidence-based cardiac care across SSA. Although research may not always be the first element considered in sustainability, it is crucial to understanding the disease burden, identifying barriers to care, and developing responsive strategies tailored to the needs of each community. A recent review highlighted how gaps in research data, statistical modeling, funding, and policy have left an estimated one billion people with cardiovascular conditions unaccounted for in SSA [19]. The GHF recognizes this importance and prioritizes research initiatives that strengthen clinical understanding to inform national policies guiding workforce training.

In 2017, the GHF supported research teams in Ethiopia, collaborating closely with the Ministry of Health to advance RHD prevention. These efforts are grounded in supporting studies such as the multi-center analysis of 6,275 patients across Ethiopian referral hospitals, which identified rheumatic valvular heart disease as the most common cardiovascular diagnosis [20]. The partnership culminated in the development of national guidelines for benzathine penicillin G prophylaxis. Coordinated by Addis Ababa University, this initiative refined treatment protocols to broaden access and reduce the risk of RHD. Simultaneously, the RHD Training Center of Excellence in Ethiopia, also supported by GHF, standardized RHD care and provided echocardiography training to over 150 nurses and physicians to strengthen early diagnosis and timely intervention. The center continues to embed research in clinical training environments, empowering local physicians to make data-driven decisions in clinical practice.

Additionally, the first study on subjective well-being among patients with RHD highlighted the psychosocial impact of the disease. It identified factors such as age at diagnosis, family income, psychological support, and access to surgery as key predictors of subjective well-being, especially among children and unmarried young women [21]. These findings not only highlight the importance of disease treatment but also reinforce the essential role of research in unpacking the complex interplay between disease and human health outcomes. Another ongoing study in Ethiopia led to the development of a national registry that tracks over 10,000 patients with RHD awaiting surgery to provide critical insights for service planning and advocacy. A similar research model is underway in Tanzania, where the KCMC launched one of the region’s first large-scale RHD prevalence studies in 2020. More than 1,000 school-aged children and 500 patients were screened to better understand the prevalence, risk factors, management, and outcomes of RHD. These findings are actively shared with the Ministry of Health to help shape cardiovascular health strategies.

The implementation of clinical and research programs has increased awareness among local cardiac teams, prompting systematic evaluation of areas requiring improvement. In 2024, the Pediatric Heart Initiative was launched in Ethiopia to train general pediatricians in echocardiography at university hospitals outside the capital city in the early diagnosis of congenital and acquired heart diseases, thereby facilitating timely medical interventions. Additionally, a women’s heart care program with a focus on cardio-obstetrics was established in Tanzania and Ethiopia to address the growing burden of cardiovascular related maternal mortality. It is well established that Africa bears a disproportionate burden of global HIV prevalence. Fortunately, the emergence of antiretroviral therapy (ART) has enabled people diagnosed with HIV to live longer. However, this increased longevity has introduced new health challenges. A recent study from KCMC in Tanzania found that both HIV and ART are associated with increased rates of metabolic syndrome and elevated blood pressure, compounding cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk in people living with HIV. These findings have prompted updates to institutional protocols to better address the intersection of HIV and cardiovascular care [22]. Data collected from these programs will contribute to a better understanding of long-term healthcare needs and formulate strategies for governmental policy and resource allocation. Collectively, these efforts reflect a deep commitment to data-driven, locally led programs. Research remains central to informing evidence-based policymaking, strengthening the health workforce, and catalyzing system-wide innovation in cardiac care. These initiatives highlight the critical role of translating research into practice to guide both clinical care and resource allocation.

Conclusion

Sustainable models for advancing cardiac care in SSA are critical to achieving long-term outcomes. While progress has been made, short-term interventions can no longer be the default approach or be expected to drive sufficient change. Sustainable transformation requires a long-term commitment and a structured approach. To effectively scale infrastructure and strengthen team-based capacity-building, it is imperative to engage all available channels, including governments, teaching institutions, NGOs, and local stakeholders, to develop cardiac teams within the region. This includes forming strategic partnerships that expand access to e-learning and boost investments in infrastructure and the availability of consumables. Equally important is locally led research, which forms the evidentiary backbone of this model. This research provides insights into the burden and distribution of disease, social and structural barriers to care, and strategies that are most effective within a given context. This ensured that the interventions were culturally responsive and clinically relevant. Although this framework is by no means exhaustive, it is designed to be dynamic and adaptive, which others can reasonably implement. Ultimately, the global medical community seeks to create a lasting blueprint for cardiac care that moves beyond dependency toward local empowerment, resilience, and sustainable self-sufficiency for communities across SSA.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We thank Emily Halvorson, BS for assisting in the preparation of the manuscript.

Author Contributions Statement

All authors have confirmed they have participated in drafting writing and edited the manuscript.

Funding

None.

References

2. Resources - Africa Health Agenda International Conference (AHAIC) [Internet]. Executive summary: report of the Africa Health Agenda International Conference Commission. 2022 [cited 2025 Oct 31]. Available from: https://ahaic.org/resources/.

3. Ahmat A, Okoroafor SC, Kazanga I, Asamani JA, Millogo JJS, Illou MMA, et al. The health workforce status in the WHO African Region: findings of a cross-sectional study. BMJ Glob Health. 2022 May;7(Suppl 1):e008317.

4. Health workforce requirements for universal health coverage and the sustainable development goals. Human Resources for Health Observer Series No 17. [cited 2025 Oct 31]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/server/api/core/bitstreams/c333ae13-dc11-4c37-b6d1-b68bab63c5e0/content.

5. Thornton J. “Silent but deadly”: NCDs in sub-Saharan Africa. The Lancet. 2025 Feb;405(10479):609–10.

6. Minja NW, Nakagaayi D, Aliku T, Zhang W, Ssinabulya I, Nabaale J, et al. Cardiovascular diseases in Africa in the twenty-first century: Gaps and priorities going forward. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Nov 10;9:1008335.

7. Mensah GA, Fuster V, Murray CJL, Roth GA; Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks Collaborators. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks, 1990-2022. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023 Dec 19;82(25):2350–473.

8. Ahadzi D, Gaye B, Commodore-Mensah Y. Advancing the Cardiovascular Workforce in Africa to Tackle the Epidemic of Cardiovascular Disease: The Time is Now. Glob Heart. 2023 Apr 21;18(1):20.

9. Asamani JA, Bediakon KSB, Boniol M, Munga'tu JK, Christmals CD, Okoroafor SC, et al. State of the health workforce in the WHO African Region: decade review of progress and opportunities for policy reforms and investments. BMJ Glob Health. 2024 Nov 25;7(Suppl 1):e015952.

10. Bekele A, Alayande BT, Gulilat D, White RE, Tefera G, Borgstein E. A plea for urgent action: Addressing the critical shortage of cardiothoracic surgical workforce in the COSECSA region. World J Surg. 2024 Sep;48(9):2187–98.

11. Manuel V, Jacobs JP, Edwin F. Building a Sustainable Cardiac Surgery Program in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Case of Angola. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2025 Jul;18(7):e012261.

12. Kanchi M, Kshettry VR. Can High-volume Centers in India Serve as Anesthesiology, Critical Care and Emergency Medicine Training Locations for African Physicians? J Acute Care 2022; 1 (3):119-120.

13. Einstein AJ, Shaw LJ, Hirschfeld C, Williams MC, Villines TC, Better N, et al; the; INCAPS COVID Investigators Group. International Impact of COVID-19 on the Diagnosis of Heart Disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 Jan 19;77(2):173–85.

14. Ebeye T, Lee H. Down the brain drain: a rapid review exploring physician emigration from West Africa. Glob Health Res Policy. 2023 Jun 27;8(1):23.

15. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risks 2023 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of cardiovascular diseases and risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2023. JACC. 2025 Dec 2;86(22):2167–243.

16. Aliyu IA, Bala JA, Yusuf I, Amole TG, Musa BM, Yahaya G, et al. Rheumatic Heart Disease Burden in Africa and the Need to Build Robust Infrastructure. JACC Adv. 2024 Oct 30;3(12):101347.

17. Vervoort D, Guetter CR, Munyaneza F, Trager LE, Argaw ST, Abraham PJ, et al. Non-Governmental Organizations Delivering Global Cardiac Surgical Care: A Quantitative Impact Assessment. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2022 Winter;34(4):1160–5.

18. Asante A, Wasike WSK, Ataguba JE. Health Financing in Sub-Saharan Africa: From Analytical Frameworks to Empirical Evaluation. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020 Dec;18(6):743–6.

19. Ogungbe O, Oborevwori E, Dele-Ojo BF, Ahadzi D, Hinneh T, Gaye B, et al. CVD in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Cost of Being Uncounted. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2025 Dec 2;86(22):2118–20.

20. Yadeta D, Guteta S, Alemayehu B, Mekonnen D, Gedlu E, Benti H, et al. Spectrum of cardiovascular diseases in six main referral hospitals of Ethiopia. Heart Asia. 2017 Jun 19;9(2):e010829.

21. Tadele H, Ahmed H, Mintesnot H, Gedlu E, Guteta S, Yadeta D. Subjective wellbeing among rheumatic heart disease patients at Tikur Anbessa Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: observational cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021 Dec 19;21(1):1354.

22. Mirai TE, Kilonzo KG, Sadiq AM, Muhina IAI, Kyala NJ, Marandu AA, et al. Metabolic Syndrome and Associated Factors Among People Living With HIV on Dolutegravir-Based Antiretroviral Therapy in Northern Tanzania. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care. 2024 Jan-Dec;23:23259582241306492.