Abstract

Autophagy is a conserved cellular process in which eukaryotic cells degrade and recycle intracellular material via a dedicated trafficking toward lysosomes. Under starvation, autophagy is initiated by the formation of a double-membrane organelle called the autophagosome, which originates from the closure and maturation of a transient membrane structure known as the phagophore. The precise membrane source of the phagophore and the mechanisms underlying its biogenesis remain incompletely understood. In our recent study by Da Graça et al., we show that starvation dynamically mobilizes endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-endosome contacts to initiate phagophore formation. Our data reveal that the ER–endosome interface facilitates local calcium release and phase transition, driving the mobilization of nanovesicles, which then fuse via a Rab3-dependent mechanism to assemble the phagophore. These findings highlight a central role for ER-endosome communication in the cellular response to nutritional stress and in the regulation of autophagy.

Keywords

Autophagy, Endosomes, Endoplasmic reticulum (ER), Phagophore, Contact-sites, Calcium, Rab GTPases

Autophagosome Biogenesis: State of the Art and Open Questions on Its Origin

Macroautophagy (hereafter referred to as autophagy) is a tightly regulated catabolic pathway activated during stress conditions such as nutrient deprivation (i.e., starvation), thereby supporting cellular homeostasis and survival [1,2]. This pathway mediates the clearance of cytoplasmic deleterious material, including protein aggregates and dysfunctional organelles. Autophagy proceeds through the de novo assembly of a double-membrane vesicle termed the autophagosome, which engulfs cytoplasmic cargoes and delivers them to lysosomes, where degradation occurs and the resulting products are recycled [3].

Autophagy depends on a cascade of signaling events and membrane remodeling, orchestrated by a set of autophagy-related (ATG) proteins that initiate the formation of the phagophore, the precursor of the autophagosome [4]. Under starvation, the Unc-51-like kinase 1 (ULK1) kinase complex relocates to specialized areas of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where it activates the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic subunit type 3 (PI3KC3) enzymatic complex, leading to the production of phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI3P), a lipid crucial for autophagy initiation [5,6]. This process first gives rise to the omegasome, a PI3P-enriched ER subdomain that serves as the platform for phagophore nucleation [7]. At the omegasome, PI3P recruits downstream ATG factors that drive LC3 lipidation and cargo recognition, thereby promoting phagophore elongation and its maturation into a complete autophagosome [4,7]. Notably, multiple stages of autophagosome assembly have been associated with local phase separation and ER-mediated Ca²+ release to cluster and activate initiation complexes [8,9]. Moreover, lipid transfer between membranes is critical for phagophore/autophagosome expansion [10,11], indicating that phagophore formation requires a specialized cytoplasmic microenvironment that spatially and temporally concentrates the necessary molecular machinery.

The role of ATG proteins in autophagy regulation is well established, but the precise origin of the autophagosomal membrane and the molecular events driving de novo phagophore formation remain incompletely defined. Although the omegasome is central to phagophore nucleation, growing evidence highlights ER contacts with mitochondria, the Golgi, and the plasma membrane in this process [12], emphasizing the need for further investigation into the function of ER-membrane contact sites during phagophore biogenesis.

While essential autophagic regulators like ATG9A and ATG16L1 are directly linked to endosomal trafficking, key GTPase such as endosome-located Rab5 and Rab11 also play a crucial role in autophagy [13–17]. Endosomal proteins are thus clearly implicated in autophagy, but whether endosomal membranes directly contribute to phagophore formation and their mode of interaction with the ER remain under debate.

Findings of the Published Work

Our recent study investigated the dynamic relationship between endosomal and ER membranes during starvation, and the importance of ER-endosome contact sites (EERCS) in autophagosome biogenesis [18]. The major question was to decipher whether dynamic EERCS could participate in phagophore biogenesis sequence in response to nutrient deprivation. Using a broad range of analytical techniques, including live cell imaging and biochemical purification of EERCS, we first showed that early (Rab5+) and recycling (Rab11+) endosomes successively bind to specialized regions of the ER within 15 minutes and 1 hour of nutrient deprivation, respectively. This sequential tethering highlights a dynamic interaction between endosomes and the ER during starvation. Employing an unbiased, machine learning-driven approach to analyze imaging data, we quantified triple proximity events involving early/recycling endosomes, the ER, and pre-autophagic/autophagic markers. Our findings revealed that EERCS dictate the choice of phagophore biogenesis sites at the ER, and that the nature of endosomal membranes engaged within EERCS adapts with time. Moreover, artificial stabilization of EERCS, using rapalog-induced dimerization of FRB-FKBP [19], shows alteration of autophagic processes, indicating that dynamic spatiotemporal modulation of ER-endosomes crosstalk is necessary to properly regulate phagophore biogenesis.

Having established the dynamic nature of EERCS in response to starvation, we next sought to characterize the molecular machinery that facilitates these contacts and their function. To further investigate their role during phagophore biogenesis, we established an ER-endosome proximity biotinylation protocol (split-TurboID) [20], using Rab5 and Rab11 as endosomal markers and vacuole membrane protein 1 (VMP1) as an ER marker, based on our observation that VMP1 associates with endosomal membranes during starvation. Split-TurboID combined with mass spectrometry identified a shared set of proteins present in both early (Rab5+) and recycling (Rab11+) endosomes associated EERCS. This common contactome includes the ER-resident protein Kinectin-1 (KTN1), the ER Ca²+ channels inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor, type 1 (ITPR1) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor, type 3 (ITPR3), Ca²+ sensors stromal interaction molecule (STIM1) and CDGSH iron sulfur domain-containing protein 2 (CISD2), the ER-exit site protein Sec16A, and RAB3 GTPase-activating protein catalytic subunit ½ (RAB3GAP1/2). Together, these findings suggest a unified molecular framework coordinating both EERCS waves during autophagy.

Consistent with this, we found that KTN1—known to interact with PI3P on endosomes—is required for EERCS mobilization under starvation. We also showed that localized ER Ca²+ release via ITPR1/3 at EERCS sites serves as a key trigger for autophagy initiation. These results reveal a conserved ER-endosome signaling axis that primes cells for autophagy through tightly regulated Ca²+ dynamics and spatial protein coordination. Further, we demonstrated that endosomes release a small amount of Ca²+ through a two-pore channel 1 (TPC1)-dependent mechanism, which in turn activates robust ITPR1/3-mediated Ca²+ release from the ER lumen. This highlights the critical role of ER-endosome communication within EERCS during the cellular response to starvation.

To explore how Ca²+ promotes phagophore formation at ER-endosome interface, we manipulated Ca²+ release by dedicated knockdowns and pharmacological agents. We found that EERCS supports a Ca²+-dependent phase transition at ER-exit sites (ERES) marked by Sec16A. Notably, the canonical function of ERES in coat protein complex II (COP-II) vesicle formation is repurposed when associated with EERCS and the autophagic machinery under starvation. We thus propose that, within EERCS, endosomes tether to ERES to support phagophore biogenesis, via a local Ca²+ release and phase transition within the ER-endosome interspace.

Finally, we show that the confined environment within EERCS regulates phagophore formation by locally mobilizing the small GTPase Rab3a and its regulators RAB3GAP1/2. Under starvation, Rab3a relocates to omegasomes, forming puncta that overlap with EERCS, Ca²+ release hotspots, and early autophagic markers (LC3, Double FYVE Domain Containing Protein 1 [DFCP1], FAK family kinase-interacting protein of 200 kDa, [FIP200]). Ultra-structure analyses reveal that Rab3a knockdown disrupts ER–endosome contacts, while loss of RAB3GAPs causes accumulation of dense vesicular material near endosomes, consistent with local stalled vesicle turnover. These nano-vesicles, likely Rab3a-positive, may provide membranes for phagophore initiation. Supporting this, Rab3a colocalizes with ATG9A and Rab5 at EERCS during starvation. Functionally, RAB3GAPs depletion causes excessive LC3 accumulation at EERCS, whereas Rab3a loss prevents LC3 recruitment. Altogether, our data support a Rab3a/RAB3GAPs-dependent mechanism in which starvation-induced Ca²+ release and phase transition regulate nano-vesicle biogenesis and fusion, contributing to the emergence of the nascent phagophore membrane [18].

Unsolved Questions, Future Directions and Limitations

The origin of autophagosomal membranes has been debated for decades. The ER via omegasomes has been long considered central [21], but endosomes, particularly Rab11 recycling endosomes, are also implicated in this process [22]. Our study identifies starvation-induced EERCS as hubs of phagophore initiation, mediated by the ER protein KTN1 binding to endosomal PI3P [19]. Within EERCS, endosomes tether to ERES/Sec16A positive structures, where Ca²+ release promotes protein phase separation and Rab3a-dependent fusion of endosome-derived nanovesicles, seeding proto-phagophores inside the local environment generated by ER–endosomes contacts.

Since we previously showed that endosomal membranes were rewired by starvation in a (SNX1/2) sorting nexins dependent manner [23], our current findings place endosomes as direct contributors to phagophore biogenesis, consistent with prior links between endosomal remodeling and autophagy [16,24–26]. EERCS assemble rapidly after starvation, paralleling other ER contact sites with mitochondria and plasma membrane [27,28], suggesting organelle specificity may vary with stress, context and timing of response. Thus, our data support a convergence of the “ER” and “endosome” hypotheses of autophagosome origin. Rab5/Rab11 EERCS generate local Ca²+ bursts that trigger phase transitions at ERES, consistent with roles of ITPR-mediated Ca²+ release and sarcoendoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) reuptake in phagophore maturation [9,29,30]. We further propose that endosomal derived nanovesicles, associated with ATG9 [18], fuse through a Rab3a-RAB3GAP1/2 system, consistent with previous reports showing ATG9-Rab3 colocalization [31] and recent descriptions of ATG9 vesicle subtypes [32].

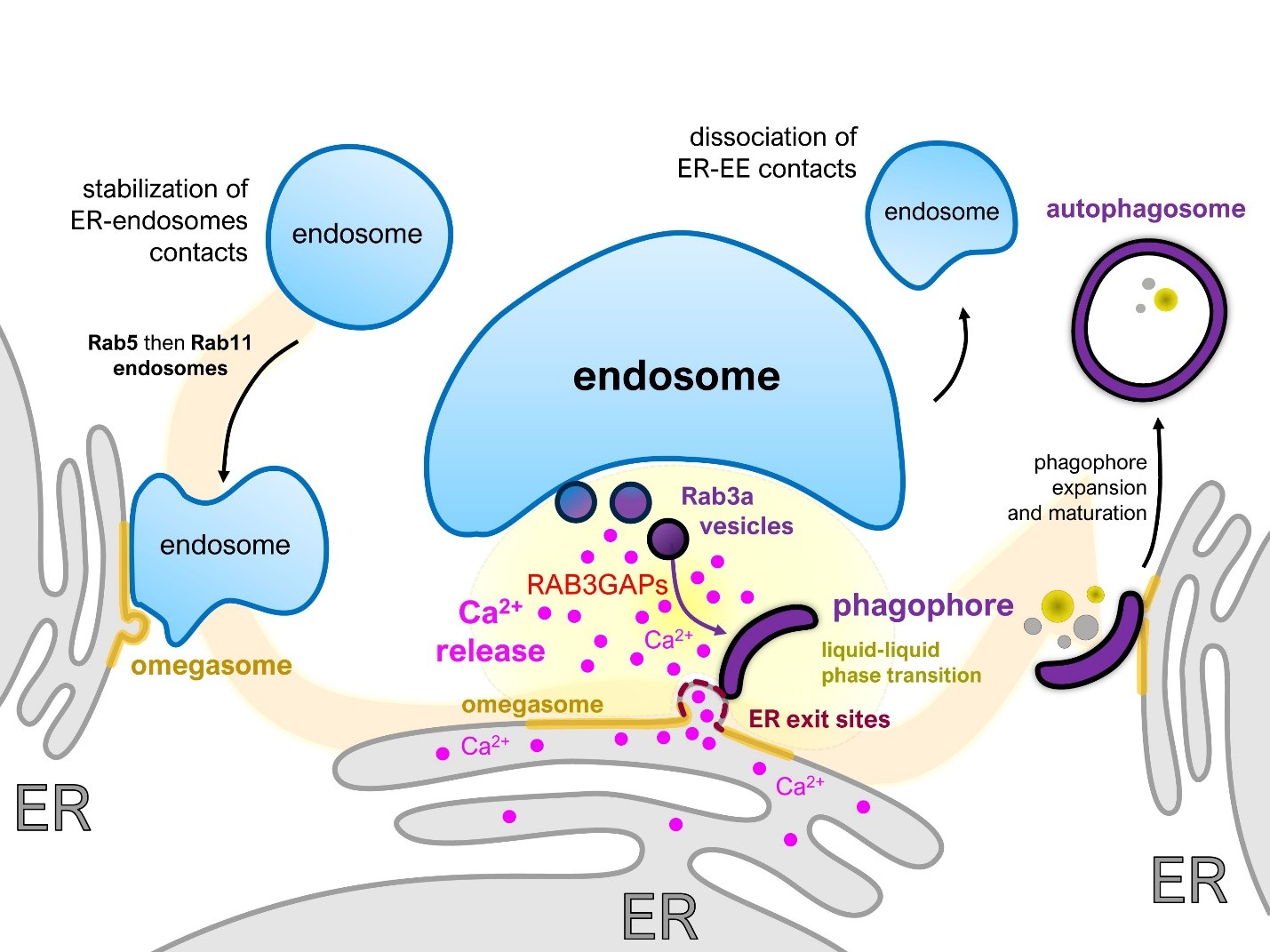

In summary (see Figure 1), our work highlights EERCS as confined, reversible microenvironment that integrate ER and endosomal dynamics to initiate phagophore formation, emphasizing the importance of organelle interactions and Ca²+ signaling in the spatial and temporal control of autophagy. Although amino acid deprivation is a potent trigger of autophagy, the contribution of ER-endosome contacts under alternative stress conditions remains to be further investigated. This is particularly relevant for cargo-specific autophagy, such as ER-phagy or mitophagy, as well as for acute cellular challenges, including mechanical forces, osmotic shock, or hypoxia. It also remains unclear whether additional ER contact sites act in parallel with ER-endosome contacts to support phagophore initiation. Additionally, while our identification of the Rab3/RAB3GAPs machinery in phagophore assembly provides a valuable insight, the complex dynamics underlying nanovesicle biogenesis and fusion during autophagy initiation remain to be further characterized. These processes warrant deeper and more systematic investigation, which may be further elucidated by ongoing research into ATG9 vesicle mobilization during the early stages of autophagy. Despite these open questions, our findings highlight the importance of ER-endosome communication in stress adaptation and provide a framework for future investigations into the early stages of autophagy.

Figure 1. ER- endosomes contacts regulate phagophore biogenesis. During acute starvation, EERCS are stabilized at omegasomes in two successive waves, first engaging Rab5-positive and later Rab11-positive endosomes. These endosomes dock onto remodeled ER exit sites, where they initiate a modest endosomal Ca²+ release, which triggers a larger ER-derived Ca²+ efflux inside the ER-endosome interspace. The confined geometry of EERCS restricts Ca²+ diffusion, creating a locally concentrated signal that promotes protein phase separation. Under these conditions, the small GTPase Rab3A is recruited to EERCS and drives the generation of nanovesicles. There, the Ca²+ activates RAB3GAP1 and RAB3GAP2, which facilitates the fusion of the Rab3A nanovesicles into a proto-phagophore. Once the latter is formed, endosomes disengage from the ER, enabling phagophore expansion and progression toward autophagosome maturation.

Given the central role of autophagy regulation in human pathologies such as neurodegenerative disorders and cancer, our findings highlight ER-endosome communication as a promising new focus in curative biology research. This perspective is particularly relevant in cancer, where disruption of autophagic flux is a well-established hallmark of tumorigenesis [33]. In receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK)-driven malignancies, such as acute myeloid leukemia [34–36], alterations of the endosomal network that governs RTK signaling are likely to affect ER-endosome contacts as well, thereby perturbing autophagosome biogenesis. Deciphering the dynamics of these ER-endosome contact sites in cancer could therefore open novel avenues for therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors received financial support from INSERM, CNRS, Université-Paris Cité, Agence Nationale pour la Recherche (ANR-17-CE140030-02, ANR-17-CE13-0015-003, ANR 22-CE14-0019 and ANR 18-CE14-0006 and Fondation pour la Recherche Médicale (FRM) “labellisation equipe” (to EM). JDG is a recipient of a fellowship from the French Ministry of Research and a 4th year PhD FRM scholarship (FDT202304016558).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

2. Boya P, Reggiori F, Codogno P. Emerging regulation and functions of autophagy. Nat Cell Biol. 2013 Jul;15(7):713–20.

3. Kawabata T, Yoshimori T. Autophagosome biogenesis and human health. Cell Discov. 2020 Jun 2;6(1):33.

4. Carlsson SR, Simonsen A. Membrane dynamics in autophagosome biogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2015 Jan 15;128(2):193–205.

5. Claude-Taupin A, Morel E. Phosphoinositides: Functions in autophagy-related stress responses. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2021 Jun;1866(6):158903.

6. Nascimbeni AC, Codogno P, Morel E. Local detection of PtdIns3P at autophagosome biogenesis membrane platforms. Autophagy. 2017 Sep 2;13(9):1602–12.

7. Zhen Y, Stenmark H. Autophagosome Biogenesis. Cells. 2023 Feb 20;12(4):668.

8. Fujioka Y, Tsuji T, Kotani T, Kumeta H, Kakuta C, Fujimoto T, et al. Phase separation promotes Atg8 lipidation for autophagy progression. bioRxiv. 2024 Aug 30:2024–08.

9. Zheng Q, Chen Y, Chen D, Zhao H, Feng Y, Meng Q, et al. Calcium transients on the ER surface trigger liquid-liquid phase separation of FIP200 to specify autophagosome initiation sites. Cell. 2022 Oct 27;185(22):4082–98.e22.

10. Gómez-Sánchez R, Rose J, Guimarães R, Mari M, Papinski D, Rieter E, et al. Atg9 establishes Atg2-dependent contact sites between the endoplasmic reticulum and phagophores. J Cell Biol. 2018 Aug 6;217(8):2743–63.

11. Valverde DP, Yu S, Boggavarapu V, Kumar N, Lees JA, Walz T, et al. ATG2 transports lipids to promote autophagosome biogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2019 Jun 3;218(6):1787–98.

12. Morel E. Endoplasmic Reticulum Membrane and Contact Site Dynamics in Autophagy Regulation and Stress Response. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2020 May 29;8:343.

13. Wei B, Fu Y, Li X, Chen F, Zhang Y, Chen H, et al. ANKFY1 bridges ATG2A-mediated lipid transfer from endosomes to phagophores. Cell Discov. 2024 Apr 16;10(1):43.

14. Moreau K, Ravikumar B, Renna M, Puri C, Rubinsztein DC. Autophagosome precursor maturation requires homotypic fusion. Cell. 2011 Jul 22;146(2):303–17.

15. Zavodszky E, Vicinanza M, Rubinsztein DC. Biology and trafficking of ATG9 and ATG16L1, two proteins that regulate autophagosome formation. FEBS Lett. 2013 Jun 27;587(13):1988–96.

16. Puri C, Vicinanza M, Ashkenazi A, Gratian MJ, Zhang Q, Bento CF, et al. The RAB11A-Positive Compartment Is a Primary Platform for Autophagosome Assembly Mediated by WIPI2 Recognition of PI3P-RAB11A. Dev Cell. 2018 Apr 9;45(1):114–31.

17. Bento CF, Puri C, Moreau K, Rubinsztein DC. The role of membrane-trafficking small GTPases in the regulation of autophagy. J Cell Sci. 2013 Mar 1;126(Pt 5):1059–69.

18. Da Graça J, Thiola C, Rouabah M, Guerrera IC, El Khallouki N, Romao M, et al. ER-endosome contacts generate a local environment promoting phagophore formation. Cell Rep. 2025 Jul 22;44(7):115993.

19. Jang W, Puchkov D, Samsó P, Liang Y, Nadler-Holly M, Sigrist SJ, et al. Endosomal lipid signaling reshapes the endoplasmic reticulum to control mitochondrial function. Science. 2022 Dec 16;378(6625):eabq5209.

20. Cho KF, Branon TC, Udeshi ND, Myers SA, Carr SA, Ting AY. Proximity labeling in mammalian cells with TurboID and split-TurboID. Nat Protoc. 2020 Dec;15(12):3971–99.

21. Ktistakis NT. ER platforms mediating autophagosome generation. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids. 2020 Jan;1865(1):158433.

22. Rubinsztein DC, Shpilka T, Elazar Z. Mechanisms of autophagosome biogenesis. Curr Biol. 2012 Jan 10;22(1):R29–34.

23. Da Graça J, Charles J, Djebar M, Alvarez-Valadez K, Botti J, Morel E. A SNX1-SNX2-VAPB partnership regulates endosomal membrane rewiring in response to nutritional stress. Life Sci Alliance. 2022 Dec 30;6(3):e202201652.

24. Knævelsrud H, Søreng K, Raiborg C, Håberg K, Rasmuson F, Brech A, et al. Membrane remodeling by the PX-BAR protein SNX18 promotes autophagosome formation. J Cell Biol. 2013 Jul 22;202(2):331–49.

25. Søreng K, Munson MJ, Lamb CA, Bjørndal GT, Pankiv S, Carlsson SR, et al. SNX18 regulates ATG9A trafficking from recycling endosomes by recruiting Dynamin-2. EMBO Rep. 2018 Apr;19(4):e44837.

26. Szatmári Z, Kis V, Lippai M, Hegedus K, Faragó T, Lorincz P, et al. Rab11 facilitates cross-talk between autophagy and endosomal pathway through regulation of Hook localization. Mol Biol Cell. 2014 Feb;25(4):522–31.

27. Nascimbeni AC, Giordano F, Dupont N, Grasso D, Vaccaro MI, Codogno P, et al. ER-plasma membrane contact sites contribute to autophagosome biogenesis by regulation of local PI3P synthesis. EMBO J. 2017 Jul 14;36(14):2018–33.

28. Hamasaki M, Furuta N, Matsuda A, Nezu A, Yamamoto A, Fujita N, et al. Autophagosomes form at ER-mitochondria contact sites. Nature. 2013 Mar 21;495(7441):389–93.

29. Decuypere JP, Parys JB, Bultynck G. ITPRs/inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors in autophagy: From enemy to ally. Autophagy. 2015;11(10):1944–8.

30. Zhao YG, Chen Y, Miao G, Zhao H, Qu W, Li D, et al. The ER-Localized Transmembrane Protein EPG-3/VMP1 Regulates SERCA Activity to Control ER-Isolation Membrane Contacts for Autophagosome Formation. Mol Cell. 2017 Sep 21;67(6):974–89.e6.

31. Yang S, Park D, Manning L, Kargbo-Hill SE, Cao M, Xuan Z, et al. Presynaptic autophagy is coupled to the synaptic vesicle cycle via ATG-9. Neuron. 2022 Mar 2;110(5):824–40.

32. Fesenko M, Moore DJ, Ewbank P, Courthold E, Royle SJ. ATG9A vesicles are a subtype of intracellular nanovesicle. J Cell Sci. 2025 Apr 1;138(7):jcs263852.

33. Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell. 2008 Jan 11;132(1):27–42.

34. Parachoniak CA, Park M. Dynamics of receptor trafficking in tumorigenicity. Trends Cell Biol. 2012 May;22(5):231–40.

35. Hwang DY, Eom JI, Jang JE, Jeung HK, Chung H, Kim JS, et al. Inhibition as a targeted therapeutic strategy for FLT3-ITD-mutated acute myeloid leukemia. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020 May 11;39(1):85.

36. Poillet-Perez L, Sarry JE, Joffre C. Autophagy is a major metabolic regulator involved in cancer therapy resistance. Cell Rep. 2021 Aug 17;36(7):109528.