Abstract

GEMIN5 is a modular RNA-binding protein responsible for the recognition of snRNAs through its WD40 domain placed at the N-terminus. A dimerization module at the central region of the protein acts as a hub for protein-protein interaction, and a non-canonical RNA-binding domain is placed towards the C-terminus. Recent studies reported loss of function Gemin5 biallelic variants which develop cerebellar ataxia, hypotonia and neurodevelopmental delay, indicating that GEMIN5 deficiency is detrimental for survival. This commentary highlights the functional and structural features of GEMIN5 and how this information contributes to the understanding of protein malfunction.

Keywords

RNA-binding proteins, Gemin5 variants, Neurodevelopmental disease, Survival of Motor Neurons (SMN) complex

Background on Functional and Structural Features of GEMIN5

GEMIN5 was first identified as a member of the survival of motor neurons (SMN) complex in human cells [1]. This macromolecular complex, formed by SMN, GEMINs 2-8 and unr-interacting protein (UNRIP) [2], is responsible for the biogenesis of small nuclear ribonucleoprotein (snRNP) complexes, the major components of the spliceosome machinery [3]. In this complex, GEMIN5 recognizes the snRNA site (5′-AAUUUUUG-3′) and delivers snRNAs to the SMN complex allowing Sm core assembly in the cytoplasm [4,5], prior to the import of SMN and snRNPs into the nucleus [6]. Remarkably, low levels of SMN protein are associated with spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), a neurodegenerative disease caused by survival motor neuron 1 (SMN1) deficiency [7]. This deficit contributes to inefficient spliceosomal snRNPs biogenesis and perturbation in alternative splicing events relevant for motor neuron function and maintenance [8,9].

Clinical variants specifically affecting the Gemin5 gene have been recently described [10, reviewed in 11,12]. Interestingly, GEMIN5 pathological variants jeopardize alternative splicing [13]. Moreover, homozygous GEMIN5 variants generated in induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC)-derived neurons show snRNP assembly deficit, resulting in global splicing defects [14]. High levels of GEMIN5 expression upregulate alternative splicing (AS) events relative to normal expression levels, being exon skipping the most frequent type of AS event. Remarkably, identification of the mRNAs associated with heavy polysomes indicated that a significant fraction of the AS mRNAs is engaged in translationally active polysomes [15]. How GEMIN5 upregulation takes over the abnormal consequences on AS splicing remains unknown. However, it is plausible that high levels of GEMIN5 favor gathering of intermediate complexes with GEMI N3 and GEMIN4, threatening the assembly of the SMN complex [16].

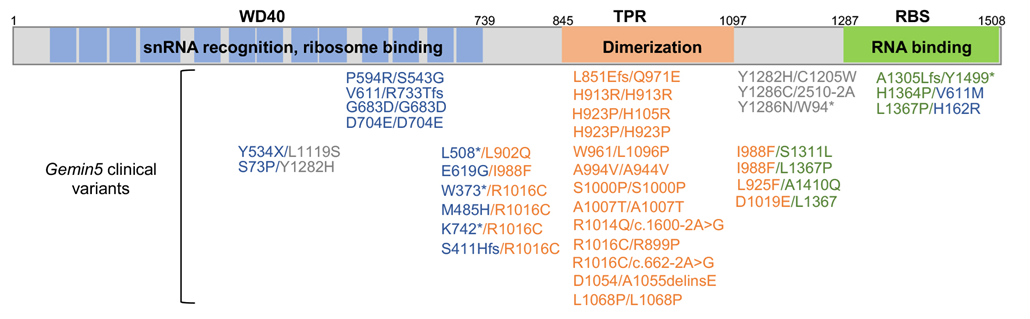

GEMIN5 is a modular protein, comprising the WD40 at the N-terminus, a tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR) dimerization module in the central region, and a non-canonical RNA binding site (RBS) at the C-terminus [17] (Figure 1). The WD40 domain consists of two seven-bladed β propellers, which recognize the Sm site and the m7G cap of pre-snRNAs [18,19]. Mutations within residues of the helixes of the TPR module destabilize the dimer conformation, leading to protein dysfunction [20,21]. Evolutionarily conserved aromatic and positive charged amino acids within the RBS domain are critical for RNA recognition [22]. Furthermore, the three-dimensional structure of the half C-terminal region underscores an oligomer complex, consisting of a dimer of pentamers [23]. The decamer architecture unveiled a cavity that includes positively charged residues of the TPR in front of RBS residues, involved in RNA-binding. This macromolecular structure suggests a role as an assembly platform, presumably relevant for its function and vulnerability to mutation. Nevertheless, since the three-dimensional structure of the full-length GEMIN5 protein is not known, this question should be addressed in future studies.

Findings of the Regulatory Roles of GEMIN5

Beyond its role in snRNPs assembly [4,5], GEMIN5 exerts an important role in translation regulation by interacting with specific mRNAs [24–27]. Furthermore, the RBS1 moiety within the RBS region promotes translation of its own mRNA [28], counteracting the negative effect of GEMIN5 on protein synthesis [24]. The regulatory role of GEMIN5 in translation has been further investigated by identifying the mRNAs associated with polysomes in Gemin5 silenced cells [29]. GEMIN5 enhances the translation of mRNAs encoding core cellular machinery (e.g., ribosomal proteins and histones), while it represses transcripts for signaling molecules (e.g., kinases) and membrane proteins, suggesting the implication of GEMIN5 in cellular metabolism by direct or indirect mechanisms.

Besides the ribosome binding ability of GEMIN5 [30], separate domains of this protein interact with distinct components of cellular networks depending upon the capacity of the protein stretch to oligomerize with the endogenous protein [31]. Dimerization mutants, as well as those affecting the phosphorylation state of the TPR module disrupt the GEMIN5 interactome [21,32,33]. Moreover, the RNA-binding intensity of GEMIN5 is enhanced in response to poly I:C treatment, a dsRNA mimic which activates signaling pathways. Likewise, treatment of cells with kinase inhibitors turns back the GEMIN5 RNA-binding strength to its baseline level, suggesting that ERK1/2 and CK2 influence the phosphorylation level of GEMIN5 [32]. Nevertheless, due to the high number of phosphoresidues found under different conditions (www.phosphosite.org), it is likely that additional kinases are involved in GEMIN5 post-translation modification. This finding adds a new layer of regulation for this essential protein, likely modulating GEMIN5 function in response to cellular cues, the dysregulation of which might contribute to disease.

Insights of Gemin5 Variants Associated with Neurodevelopmental Disease

The essential function of GEMIN5 is consistent with the embryonic lethal phenotype of model animal systems [10,34,35]. In humans, GEMIN5 is encoded by a single gene, located in the chromosome 5q33. The primary transcript comprises 28 exons encoding a 170 kDa protein, expressed in all human tissues. In the last years, mutations in Gemin5 gene have been detected in patients with neurodevelopmental disorders, compatible with the expression of a defective protein [10,14,21]. Patients harboring Gemin5 biallelic variants display distinct degrees of cerebellar atrophy, motor disfunction, ataxia, cognitive delay, and hypotonia. Cerebellar atrophy is observed in most patients, suggesting that this is a specific phenotypic trait associated with Gemin5 variants. The term “neurodevelopmental disorder with cerebellar atrophy and motor dysfunction” (NEDCAM) has been proposed to describe the clinical disorders associated with homozygous or compound heterozygous mutations in Gemin5 gene [14]. This autosomal recessive disorder is characterized by global developmental delay with prominent motor abnormalities, mainly axial hypotonia, gait ataxia, and appendicular spasticity. Patients have cognitive impairment and speech delay; brain imaging shows cerebellar atrophy. Remarkably, the Gemin5 neurodevelopmental ataxia spectrum differs from the neuromuscular symptoms caused in SMA patients by deficiencies of the SMN protein, characterized by muscle weakness and atrophy, scoliosis, breathing problems and hypotonia. These differences support the proposition that GEMIN5 deficiency leads to a distinctive neurodevelopmental disease.

The vast majority of the currently reported variants affect the dimerization module or combine mutations in the TPR with the WD40 or the RBS domains (Figure 1), highlighting the relevance of maintaining the TPR-dependent oligomeric architecture for normal protein function. Accordingly, our studies using both the R1016C and D1019D replacements, which are located on a loop between helixes 12 and 13 with their side chains involved in a network of electrostatic interactions, induce conformational changes on the homodimer structure, disrupting the regulatory functions of this protein [21]. In the particular case of R1016C, the recessive mutation in one allele is accompanied by either a truncated version, a frameshift or an intron variant in the other allele. In other patients, the second allele contains a mutant on the WD40, the TPR or the RBS domains (Figure 1). Besides R1016C, several variants appear recurrently in different patients (H923P, I988P, D1019E, or L1367P), supporting a key role of these residues in protein malfunction.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of GEMIN5 modular domains. Gemin5 variants associated with neurodevelopmental disorders are colored according to the domain affected.

The disease spectrum associated with GEMIN5 deficiency has recently increased with the identification of additional clinical variants, consequently highlighting the relevance of the dimerization domain for the physiological functions of this protein [36–39]. Intellectual disability, cerebellar atrophy, motor dysfunction and speech impairment were associated to D1054/A1055delinsE in one of the alpha helixes of the TPR module [37]. Another study conducted in fibroblasts generated from two patients with Gemin5 variants K742*/R1016C and R1016C/S411H* reports a decrease in CoQ10 biosynthesis compared to fibroblast from controls. This finding prompted the treatment of patients with CoQ10, leading to partial recovery following long-treatment [38]. However, whether this treatment will work for other patients remains elusive. Other examples of disease spectrum are found in patients with infantile developmental and epileptic encephalopathies [39]. These patients carry biallelic variants affecting the TPR and the RBS domains, expanding the disorders associated with Gemin5 mutations. It is likely that in the near future a deeper knowledge of the protein activities will help to better understand the phenotypic spectrum of Gemin5 variants.

Future Directions

This commentary highlights the hallmarks of GEMIN5, a protein with key roles in spliceosome assembly and regulation of translation. Identification of the WD40 domain as the snRNAs interacting region provided the basis for the molecular function of GEMIN5. Later on, the structural features of the TPR dimerization module and the non-canonical RBS served as a central point for recognizing Gemin5 variants in patients developing neurodevelopmental disorders, which were defective in protein oligomerization. Since GEMIN5 has been shown to oligomerize, it is likely that the expression of frameshift and termination variants might perturb normal protein folding. In turn, these alterations might disrupt the ability of GEMIN5 to form a complex with snRNP proteins and exert physiological functions, ultimately leading to neurological disorders. Future work should determine whether patient derived variants disrupt the decamer structure and its proposed RNA-binding cavity. Additionally, abnormal GEMIN5 function might affect translation of mRNAs either ubiquitously or in a tissue-specific manner.

GEMIN5 variants disrupt a distinct set of transcripts compared to SMA patients, implying different molecular mechanisms related to defects in SMN or GEMIN5. However, establishing a link between cerebellar atrophy and Gemin5 loss of function is an arduous task. A key challenge is to identify whether cerebellar atrophy stems from defective snRNP assembly in specific neuronal transcripts, dysregulated translation of a subset of mRNAs critical for cerebellar function or a combination of both. Integrating functional and structural studies with clinical and functional genomics can improve the diagnosis of Gemin5 patients, although uncovering the structure, mechanisms, and functions of this protein within the context of human disease is challenging. To bridge this gap, the use of patient derived iPSC neurons or novel animal models can be useful. Therefore, structural and functional studies of Gemin5 variants identified in patients, in conjunction with exhaustive identification of the clinical traits, should open new avenues to explore the molecular mechanisms involved in GEMIN5 malfunction, and eventually help in the development of potential therapeutic targets.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by grant PID2023-148273NB-I00 from Ministerio de Ciencia y Universidad (MICIU/AEI). We thank former lab members for their contribution to the work described in the commentary.

Conflicting Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

2. Otter S, Grimmler M, Neuenkirchen N, Chari A, Sickmann A, Fischer U. A comprehensive interaction map of the human survival of motor neuron (SMN) complex. J Biol Chem. 2007 Feb 23;282(8):5825–33.

3. Kastner B, Will CL, Stark H, Lührmann R. Structural Insights into Nuclear pre-mRNA Splicing in Higher Eukaryotes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2019 Nov 1;11(11):a032417.

4. Battle DJ, Lau CK, Wan L, Deng H, Lotti F, Dreyfuss G. The Gemin5 protein of the SMN complex identifies snRNAs. Mol Cell. 2006 Jul 21;23(2):273–9.

5. Lau CK, Bachorik JL, Dreyfuss G. Gemin5-snRNA interaction reveals an RNA binding function for WD repeat domains. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009 May;16(5):486–91.

6. Raimer AC, Gray KM, Matera AG. SMN - A chaperone for nuclear RNP social occasions? RNA Biol. 2017 Jun 3;14(6):701–11.

7. Burghes AH, Beattie CE. Spinal muscular atrophy: why do low levels of survival motor neuron protein make motor neurons sick? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009 Aug;10(8):597–609.

8. Coady TH, Lorson CL. SMN in spinal muscular atrophy and snRNP biogenesis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2011 Jul-Aug;2(4):546–64.

9. Zhang Z, Lotti F, Dittmar K, Younis I, Wan L, Kasim M, et al. SMN deficiency causes tissue-specific perturbations in the repertoire of snRNAs and widespread defects in splicing. Cell. 2008 May 16;133(4):585–600.

10. Rajan DS, Kour S, Fortuna TR, Cousin MA, Barnett SS, Niu Z, et al. Autosomal Recessive Cerebellar Atrophy and Spastic Ataxia in Patients With Pathogenic Biallelic Variants in GEMIN5. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2022 Feb 28;10:783762.

11. Nelson CH, Pandey UB. Function and dysfunction of GEMIN5: understanding a novel neurodevelopmental disorder. Neural Regen Res. 2024 Nov 1;19(11):2377–86.

12. Martinez-Salas E, Francisco-Velilla R. GEMIN5 and neurodevelopmental diseases: From functional insights to disease perception. Neural Regen Res. 2026 Jan 1;21(1):187–94.

13. Fortuna TR, Kour S, Chimata AV, Muiños-Bühl A, Anderson EN, Nelson Iv CH, et al. SMN regulates GEMIN5 expression and acts as a modifier of GEMIN5-mediated neurodegeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2023 Sep;146(3):477–98.

14. Kour S, Rajan DS, Fortuna TR, Anderson EN, Ward C, Lee Y, et al. Loss of function mutations in GEMIN5 cause a neurodevelopmental disorder. Nat Commun. 2021 May 7;12(1):2558.

15. Francisco-Velilla R, Abellan S, Garcia-Martin JA, Oliveros JC, Martinez-Salas E. Alternative splicing events driven by altered levels of GEMIN5 undergo translation. RNA Biol. 2024 Jan;21(1):23–34.

16. Battle DJ, Kasim M, Wang J, Dreyfuss G. SMN-independent subunits of the SMN complex. Identification of a small nuclear ribonucleoprotein assembly intermediate. J Biol Chem. 2007 Sep 21;282(38):27953–9.

17. Martinez-Salas E, Abellan S, Francisco-Velilla R. Understanding GEMIN5 Interactions: From Structural and Functional Insights to Selective Translation. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2025 Mar-Apr;16(2):e70008.

18. Jin W, Wang Y, Liu CP, Yang N, Jin M, Cong Y, et al. Structural basis for snRNA recognition by the double-WD40 repeat domain of Gemin5. Genes Dev. 2016 Nov 1;30(21):2391–403.

19. Xu C, Ishikawa H, Izumikawa K, Li L, He H, Nobe Y, et al. Structural insights into Gemin5-guided selection of pre-snRNAs for snRNP assembly. Genes Dev. 2016 Nov 1;30(21):2376–90.

20. Moreno-Morcillo M, Francisco-Velilla R, Embarc-Buh A, Fernández-Chamorro J, Ramón-Maiques S, Martinez-Salas E. Structural basis for the dimerization of Gemin5 and its role in protein recruitment and translation control. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020 Jan 24;48(2):788–801.

21. Francisco-Velilla R, Embarc-Buh A, Del Caño-Ochoa F, Abellan S, Vilar M, Alvarez S, et al. Functional and structural deficiencies of Gemin5 variants associated with neurological disorders. Life Sci Alliance. 2022 Apr 7;5(7):e202201403.

22. Embarc-Buh A, Francisco-Velilla R, Camero S, Pérez-Cañadillas JM, Martínez-Salas E. The RBS1 domain of Gemin5 is intrinsically unstructured and interacts with RNA through conserved Arg and aromatic residues. RNA Biol. 2021 Oct 15;18(sup1):496–506.

23. Guo Q, Zhao S, Francisco-Velilla R, Zhang J, Embarc-Buh A, Abellan S, Lv M, et al. Structural basis for Gemin5 decamer-mediated mRNA binding. Nat Commun. 2022 Sep 2;13(1):5166.

24. Pacheco A, López de Quinto S, Ramajo J, Fernández N, Martínez-Salas E. A novel role for Gemin5 in mRNA translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009 Feb;37(2):582–90.

25. Bradrick SS, Gromeier M. Identification of gemin5 as a novel 7-methylguanosine cap-binding protein. PLoS One. 2009 Sep 14;4(9):e7030.

26. Workman E, Kalda C, Patel A, Battle DJ. Gemin5 Binds to the Survival Motor Neuron mRNA to Regulate SMN Expression. J Biol Chem. 2015 Jun 19;290(25):15662–9.

27. Van Nostrand EL, Pratt GA, Yee BA, Wheeler EC, Blue SM, Mueller J, et al. Principles of RNA processing from analysis of enhanced CLIP maps for 150 RNA binding proteins. Genome Biol. 2020 Apr 6;21(1):90.

28. Francisco-Velilla R, Fernandez-Chamorro J, Dotu I, Martinez-Salas E. The landscape of the non-canonical RNA-binding site of Gemin5 unveils a feedback loop counteracting the negative effect on translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018 Aug 21;46(14):7339–53.

29. Embarc-Buh A, Francisco-Velilla R, Garcia-Martin JA, Abellan S, Ramajo J, Martinez-Salas E. Gemin5-dependent RNA association with polysomes enables selective translation of ribosomal and histone mRNAs. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2022 Aug 20;79(9):490.

30. Francisco-Velilla R, Fernandez-Chamorro J, Ramajo J, Martinez-Salas E. The RNA-binding protein Gemin5 binds directly to the ribosome and regulates global translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016 Sep 30;44(17):8335–51.

31. Francisco-Velilla R, Abellan S, Embarc-Buh A, Martinez-Salas E. Oligomerization regulates the interaction of Gemin5 with members of the SMN complex and the translation machinery. Cell Death Discov. 2024 Jun 28;10(1):306.

32. Abellan S, Escos A, Francisco-Velilla R, Martinez-Salas E. Impact of Gemin5 in protein synthesis: phosphoresidues of the dimerization domain regulate ribosome binding. RNA Biol. 2025 Dec;22(1):1–15.

33. Francisco-Velilla R, Embarc-Buh A, Abellan S, Del Caño-Ochoa F, Ramón-Maiques S, Martinez-Salas E. Phosphorylation of T897 in the dimerization domain of Gemin5 modulates protein interactions and translation regulation. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2022 Nov 11;20:6182–91.

34. Gates J, Lam G, Ortiz JA, Losson R, Thummel CS. rigor mortis encodes a novel nuclear receptor interacting protein required for ecdysone signaling during Drosophila larval development. Development. 2004 Jan;131(1):25–36.

35. Saida K, Tamaoki J, Sasaki M, Haniffa M, Koshimizu E, Sengoku T, et al. Pathogenic variants in the survival of motor neurons complex gene GEMIN5 cause cerebellar atrophy. Clin Genet. 2021 Dec;100(6):722–30.

36. Zhang X, Guo Y, Xu L, Wang Y, Sheng G, Gao F, et al. Novel compound heterozygous mutation and phenotype in the tetratricopeptide repeat-like domain of the GEMIN5 gene in two Chinese families. J Hum Genet. 2023 Nov;68(11):789–92.

37. Ibrahim N, Naz S, Mattioli F, Guex N, Sharif S, Iqbal A, et al. A Biallelic Truncating Variant in the TPR Domain of GEMIN5 Associated with Intellectual Disability and Cerebral Atrophy. Genes (Basel). 2023 Mar 13;14(3):707.

38. Cascajo-Almenara MV, Juliá-Palacios N, Urreizti R, Sánchez-Cuesta A, Fernández-Ayala DM, García-Díaz E, et al. Mutations of GEMIN5 are associated with coenzyme Q10 deficiency: long-term follow-up after treatment. Eur J Hum Genet. 2024 Apr;32(4):426–34.

39. Zhang J, Liu X, Zhu G, Wan L, Liang Y, Li N, et al. Expanding the clinical phenotype and genetic spectrum of GEMIN5 disorders: Early-infantile developmental and epileptic encephalopathies. Brain Behav. 2024 May;14(5):e3535.