Abstract

Introduction: Hyponatremia, observed in 15–30% heart failure (HF) patients, is associated with poor long-term outcomes in these patients. However, its prognostic significance during hospitalization remains unclear, therefore our study aims to fill this knowledge gap.

Objective/ Hypothesis: Is hyponatremia associated with poor outcomes in hospitalized heart failure patients?

Methods: National Inpatient Sample database was used to identify all adults with HF using ICD-10 codes. The patients were stratified into those with and without hyponatremia. Propensity score matching was performed to match the two cohorts in 1:1 ratio on age, gender, and comorbidities. Univariate analysis was performed pre- and post-matching to analyze outcomes.

Results: Out of 15,900,000 patients admitted with HF, 2,329,359 had hyponatremia. Patients with hyponatremia were younger and had a higher prevalence of hypertension. Hyponatremia patients had significantly higher mortality (8.35% vs 5.71%), cardiac arrest (2.80% vs 1.67%), cardiogenic shock (5.13% vs 2.23%) need for mechanical ventilation (9.74% vs 7.08%), use of inotropic support (1.56% vs 0.81%), balloon pump utilization (0.81% vs 0.48%), ECMO use (0.14% vs 0.09%), arrhythmia (13.92% vs 12.56%) and acute kidney injury (36.66% vs 27.93%). Furthermore, hyponatremic patients experienced a statistically significant longer length of stay (9.34 days vs 6.35 days) and higher cost of hospitalization ($128276 vs $ 77576).

Conclusion: Our findings underscore hyponatremia as not merely a laboratory abnormality, but a critical prognostic marker in the HF population. Early recognition and management of hyponatremia may be essential in improving clinical outcomes and reducing the economic burden associated with HF hospitalizations. Further prospective studies are warranted to explore causality and guide therapeutic strategies.

Keywords

Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, Hyponatremia, Mortality, Cardiac outcomes, Length of Stay, Total hospital charges, Extra corporal membrane oxygenation

Introduction

Hyponatremia, defined as a serum sodium concentration below 135 mmol/L, is the most frequent electrolyte abnormality in hospitalized patients and is particularly prevalent among those with heart failure (HF) [1]. It affects 15–30% of HF admissions and reflects advanced disease characterized by persistent congestion, heightened neurohormonal activation, and impaired renal water handling [2–4]. Beyond being a biochemical disturbance, hyponatremia has consistently been associated with increased mortality and adverse long-term outcomes, establishing it as both a marker and mediator of disease severity in HF [5,6].

Over the past two decades, advances in HF management have significantly improved survival and reduced morbidity. Guideline-directed medical therapies, including beta-blockers, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system inhibitors (RAAS), mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, neprilysin inhibitors, and more recently sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, along with device-based strategies such as implantable defibrillators and cardiac resynchronization therapy, have reshaped outcomes for many patients [7]. Despite these advances, hyponatremia remains poorly addressed. Current management strategies, largely limited to fluid restriction and cautious diuretic adjustment, have shown limited efficacy [8,9]. As a result, hyponatremia continues to contribute to hemodynamic instability, recurrent hospitalizations, and increased healthcare costs, representing an important gap in the otherwise advancing landscape of HF care.

Although its prognostic role has been well described, important gaps remain in understanding the impact of hyponatremia on acute in-hospital outcomes. Prior studies have primarily examined mortality and readmissions, while its association with complications such as cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock, arrhythmias, acute kidney injury (AKI), and the need for advanced support therapies, including inotropes, mechanical ventilation, or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), remains less defined [10–13]. Furthermore, its contribution to healthcare utilization through longer hospital stays and higher charges has not been comprehensively assessed. The present study addresses these gaps by evaluating the association between hyponatremia and a broad spectrum of in-hospital outcomes in a large, nationally representative cohort of HF patients, offering new insights into its clinical and economic burden.

Methods

Data source

We conducted a retrospective analysis using data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) spanning January 2020 through December 2022. The NIS is a nationally representative administrative database that includes discharge records from a stratified sample of hospitals across the United States, capturing nearly 97% of the U.S. population. It is maintained by the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) and supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. As the patient information is deidentified, IRB approval is exempted as per HCUP data use agreement.

Study population

The study cohort comprised adult patients (aged 18 years and older) admitted with a principal diagnosis of heart failure (HF), identified using standardized ICD-10 codes (I5020–I5043, I501, I5030–I5033, and I509). Individuals were divided into two groups: HF patients with hyponatremia and those without. Cases with hyponatremia were defined by the presence of ICD-10 code E87.1. Records with incomplete demographic or clinical information were excluded from analysis.

Comorbidities

Relevant coexisting conditions were identified using ICD-10 coding algorithms. These included hypertension (I10–I15), diabetes mellitus (E08–E13), hyperlipidemia (E78), coronary artery disease (I25), cerebrovascular disease (I63), and chronic kidney disease (N181–N189). These variables were included in the propensity score model to adjust for potential baseline imbalances between groups.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was in-hospital mortality. Secondary endpoints encompassed major in-hospital events and resource utilization, including cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock, mechanical ventilation, need for inotropic support, use of intra-aortic balloon pump and ECMO, arrhythmias, and development of acute kidney injury (AKI). Measures of hospital resource use, including total hospitalization cost (TOTCHG) and length of stay (LOS), were also evaluated. All outcomes were extracted using corresponding ICD-10 diagnosis and procedure codes.

Statistical analysis

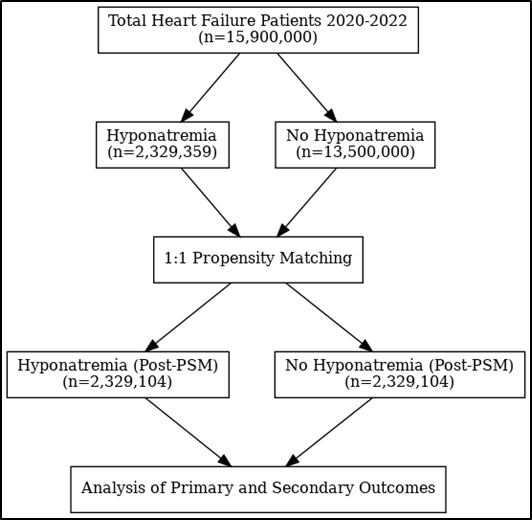

To minimize confounding, 1:1 propensity score matching was carried out, by employing Stata to perform greedy propensity matching, using the nearest-neighbor method with a caliper of 0.02. Matching variables included demographic factors (age, sex) and major comorbidities. Post matching p-values were >0.05, confirming successful matching (Figure 1). Comparisons were then performed using chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. Odds ratios (ORs) and mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were derived from logistic regression models to assess associations between hyponatremia and clinical outcomes. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were completed using STATA software.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of study design.

Results

From 2020 to 2022, a total of 15.9 million adult hospitalizations for heart failure (HF) were identified, of which 2,329,359 (14.6%) had a concurrent diagnosis of hyponatremia. In the unmatched sample, both groups were similar in baseline characteristics except that the patients with hyponatremia were slightly younger than those without hyponatremia (70.7 vs 71.3 years, p<0.001). Statistically significant differences were also observed in race and geographic distribution. A higher proportion of patients with hyponatremia were Hispanic (9.1% vs 7.6%, p<0.001), Asian (2.9% vs 2.0%, p<0.001), or American Indian (0.7% vs 0.6%, p<0.001). On the contrary, lower proportion of these patients were blacks (14.47% vs 18.47%, P<0.001) and less frequently admitted to hospitals located in the Northeast (16.23% vs 18.03%, p<0.001). Moreover, patients in hyponatremia group have more prevalent HTN (39.94% vs 34.23%, P<0.001) and CKD (33.78% vs 29.49%), while less prevalent DM (49.13% vs 53.54%, P<0.001) and CAD (44.96% vs 48.65%) (Table 1). Initial analysis revealed that patients hospitalized with heart failure (HF) and concurrent hyponatremia had significantly higher rates of in-hospital mortality (8.54% vs 5.39%; OR=1.64; 95% CI 1.62 to 1.66; p <0.01), cardiac arrest (2.80% vs 1.86%; OR=1.53; 95% CI=1.50 to 1.56; p<0.01), cardiogenic shock (5.13% vs 2.35%; OR=2.26; 95% CI= 2.22 to 2.29; p<0.01), need for mechanical ventilation (9.74% vs 6.05%; OR=1.68; 95% CI=1.66 to 1.72; p<0.01), and acute kidney injury (36.66% vs 27.74%; OR=1.51; 95% CI=1.50 to 1.52; p<0.01) compared to patients without hyponatremia. Additionally, patients with hyponatremia were more likely to require inotropic support (2.29% vs 1.17%; OR=1.99; 95% CI= 1.94 to 2.03; p<0.01), intra-aortic balloon pump (0.81% vs 0.45%; OR=1.81; 95% CI=1.74 to 1.88; p<0.01), and ECMO (0.14% vs 0.07%; OR=1.87; 95% CI=1.71 to 2.03; p<0.01). The incidence of arrhythmias was also significantly elevated in this group (13.9% vs 12.6%; OR=1.12; 95% CI= 1.11 to 1.13; p<0.01). Moreover, hyponatremic patients had significantly longer hospital stays (9.4 vs 6.2 days; MD=3.17 days; 95% CI=3.14 to 3.20; p<0.01) and greater TOTCHG ($128,280 vs $85,160; MD=$43117.25; 95% CI= 42458.6 to 43115.8; p <0.01) (Table 2).

|

Variable |

HF and hyponatremia (n=2,329,359) |

HF without hyponatremia (n=135,000,00) |

|

|

AGE |

70.72692 (70.68751 70.76633) |

71.28247 (71.26652 71.29843) |

|

|

FEMALE |

1,117,134 (47.96%) |

6,436,161 (47.67%) |

|

|

RACE |

WHITE BLACK HISPANICS ASIANS AMERICANS OTHERS |

1,634,045 (70.15%) 337,058 (14.47%) 217,562 (9.34%) 68,949 (2.96%) 17,004 (0.73%) 54,973 (2.36%) |

9,298,800 (68.88%) 2,493,450 (18.47%) 1,061,100 (7.86%) 271,350 (2.01%) 78,300 (0.58%) 297,000 (2.2%) |

|

REGION |

NORTHEAST MIDWEST SOUTH WEST |

378,055 (16.23%) 556,018 (23.87%) 960,628 (42.24%) 434,658 (18.66%) |

2,434,050 (18.03%) 3,229,200 (23.92%) 5,525,550 (40.93%) 2,312,550 (17.13%) |

|

BEDSIZE |

SMALL MEDIUM LARGE |

518,282 (22.25%) 657,578 (28.23%) 1,153,499 (49.52%) |

3,095,550 (22.93%) 3,848,850 (28.51%) 6,554,250 (48.55%) |

|

PRIMARY PAYER |

MEDICAID MEDICAID HMO SELF NO CHARGE OTHER |

1,687,155 (72.43%) 253,667 (10.89%) 281,387 (12.08%) 49,149 (2.11%) 3,494 (0.15%) 54,507 (2.34%) |

9,822,600 (72.76%) 1,393,200 (10.32%) 1,625,400 (12.04%) 294,300 (2.18%) 20,250 (0.15%) 344,250 (2.55%) |

|

HOME INCOME |

$1-$51999 $52000-$65999 $66000-$87999 $88000 or more |

720,937 (30.95%) 689,490 (26.9%) 548,564 (23.55%) 433,028 (18.59%) |

4,436,100 (32.86%) 3,622,050 (26.83%) 3,065,850 (22.71%) 2,374,650 (17.59%) |

|

COMORBIDITIES |

HTN DM HLD CAD CVA CKD |

930274.5 (39.94%) 1068204 (45.67%) 1144364 (49.13%) 1047354 (44.96%) 12105 (0.52%) 786820 (33.78%) |

4621512 (34.23%) 6023872 (44.62%) 7227861 (53.54%) 6567772 (48.65%) 51620 (0.38%) 3981508 (29.49%) |

|

OUTCOME |

HF and hyponatremia (2,329,359) |

HF without hyponatremia (135,00,000) |

Odds Ration/ Mean Difference |

P-value |

|

Mortality |

198595 (8.53%) |

728074 (5.34%) |

1.64025 (95% CI 1.6214 to 1.659319) |

P<0.001 |

|

LOS |

9.359208 |

6.190013 |

3.169195 (95% CI 3.136267 to 3.202124) |

P<0.001 |

|

TOTCHG |

128280 |

85160 |

43117.25 (95% CI 42458.66 to 43775.84) |

P<0.001 |

|

Cardiac arrest |

65250 (2.80%) |

250730 (1.86%) |

1.527599 (95% CI 1.498076 to 1.557705) |

P<0.001 |

|

Cardiogenic shock |

119485 (5.13%) |

316815 (2.35%) |

2.256873 (95% CI 2.222794 to 2.291474) |

P<0.001 |

|

Mechanical Ventilation |

226990 (9.74%) |

816810 (6.05%) |

1.681918 (95% CI 1.658906 to 1.705249) |

P<0.001 |

|

Inotropic support |

53565 (2.29%) |

158370 (1.17%) |

1.988909 (95% CI 1.945379 to 2.033412) |

P<0.001 |

|

ECMO |

3275 (0.14%) |

10200 (0.07%) |

1.867701 (95% CI 1.710237 to 2.039662) |

P<0.001 |

|

Balloon pump |

18880 (0.81%) |

60900 (0.45%) |

1.808731 (95% CI 1.743662 to 1.876228) |

P<0.001 |

|

Arrythmia |

323781 13.91%) |

1704174 (12.62%) |

1.123189 (95% CI 1.113083 to 1.133388) |

P<0.001 |

|

AKI |

853884 (36.66%) |

3745373 (27.74) |

1.513568 (95% CI 1.503722 to 1.523479) |

P<0.001 |

After matching for age, sex, race, hospital characteristics, and 15 clinical covariates including cardiovascular comorbidities and renal disease, the matched analysis validated these associations. The hyponatremia group continued to demonstrate significantly higher in-hospital mortality (8.35% vs 5.71%; OR=1.54; 95% CI=1.51 to 1.57; p=0.01), cardiac arrest (2.80% vs 1.67%; OR=1.69; 95% CI=1.64 to 1.75; p<0.01), cardiogenic shock (5.13% vs 2.23%; OR=2.37; 95% CI=2.26 to 2.49; p<0.01), mechanical ventilation (9.74% vs 7.08%; OR=1.41; 95% CI=1.38 to 1.45; p<0.01), and AKI (36.66% vs 27.93%; OR=1.49; 95% CI=1.47 to 1.52; p<0.01). Rates of arrhythmia (13.92% vs 12.56%; OR=1.13; 95% CI=1.13 to 1.10; p<0.01), inotropic support (1.56% vs 0.81%; OR=1.94; 95% CI=1.72 to 2.19; p<0.01), balloon pump use (0.81% vs 0.48%; OR=1.70; 95% CI=1.56 to 1.85; p<0.01), and ECMO (0.14% vs 0.09%; OR=1.55; 95% CI 1.29 to 1.86; p<0.01) remained significantly higher in the hyponatremic group. Additionally, these patients had longer hospital stays (9.36 vs 6.35 days; MD=3.01; 95% CI=2.92 to 3.09; p<0.01) and incurred greater hospitalization costs ($128,276 vs $77,576; MD=$50700; 95% CI=$47401.07 to $3998.38; p<0.01) (Table 3).

|

OUTCOME |

HF and hyponatremia (2,329,104) |

HF without hyponatremia (2,329,104) |

Odds Ration/ Mean Difference |

P-value |

|

Mortality |

198585 (8.35%) |

132930 (5.71%) |

1.539869 (95% CI 1.506041 to 1.574456) |

P=0.001 |

|

LOS |

9.359138 |

6.353437 |

3.005701 (95% CI 2.921633 to 3.089769) |

P<0.001 |

|

TOTCHG |

128276 |

77576 |

50700 (95% CI 47401.07 to 3998.38) |

P<0.001 |

|

Cardiac arrest |

65245 (2.80%) |

38985 (1.67%) |

1.693006 (95% CI 1.636101 to 1.751889) |

P<0.001 |

|

Cardiogenic shock |

119475 (5.13%) |

51965 (2.23%) |

2.369389 (95% CI 2.258218 to 2.486033) |

P<0.001 |

|

Mechanical Ventilation |

226975 (9.74%) |

164870 (7.08%) |

1.417363 (95% CI 1.383665 to 1.45188) |

P<0.001 |

|

Inotropic support |

36320 (1.56%) |

18835 (0.81%) |

1.943031 (95% CI 1.724981 to 2.188643) |

P<0.001 |

|

ECMO |

3275 (0.14%) |

2115 (0.09%) |

1.549237 (95% CI 1.291109 to 1.858971) |

P<0.001 |

|

Balloon pump |

18875 (0.81%) |

11165 (0.48%) |

1.696195 (95% CI 1.557619 to 1.847099) |

P<0.001 |

|

Arrythmia |

324220 (13.92%) |

292535 (12.56%) |

1.125828 (95% CI 1.098678 to 1.153648) |

P<0.001 |

|

AKI |

853794 (36.66%) |

650575 (27.93%) |

1.493145 (95% CI 1.470742 to 1.51589) |

P<0.001 |

Discussion

There is limited literature comprehensively evaluating the role of hyponatremia in determining in-hospital outcomes among patients with HF. Most prior reports have focused primarily on its prognostic role in long-term survival, leaving a gap in understanding its impact on acute complications during hospitalization [10,14–18]. In this nationally representative analysis, hyponatremia was significantly associated with higher in-hospital mortality, LOS, increased hospital charges, and greater use of intensive interventions such as inotropes, mechanical ventilation, ECMO, and intra-aortic balloon pump support. Additionally, hyponatremic patients demonstrated increased risks of cardiac arrest, cardiogenic shock, arrhythmias, and AKI, underscoring the multifaceted burden of this electrolyte abnormality.

Pathogenesis of hyponatremia

Understanding the impact of hyponatremia on HF outcomes, necessitates a thorough understanding of the pathophysiology of hyponatremia in HF. It is multifactorial and reflects the convergence of hemodynamic, neurohormonal, renal, and iatrogenic mechanisms [5]. The initiating event is typically reduced cardiac output and arterial underfilling, which activate high-pressure baroreceptors in the carotid sinus, aortic arch, and renal afferent arterioles [4,19]. This stimulates compensatory neurohormonal pathways, including sympathetic nervous system activation, RAAS, and non-osmotic release of arginine vasopressin (AVP) [4,20]. AVP acts on V2 receptors in the renal collecting ducts, leading to aquaporin-2 insertion and disproportionate free water reabsorption, diluting plasma sodium concentration [20,21]. RAAS activation further promotes sodium and water retention at the proximal and distal nephron, while aldosterone enhances distal sodium reabsorption, perpetuating volume overload. Despite total body sodium excess, the relative retention of free water results in dilutional hyponatremia [4,3]. Sympathetic overactivity worsens the problem by inducing systemic vasoconstriction, renal hypoperfusion, and reduced glomerular filtration rate (GFR), thereby limiting free water clearance. Elevated atrial and ventricular filling pressures stimulate secretion of atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP), which normally counterbalance RAAS and AVP through vasodilation, natriuresis, and inhibition of renin release [22,23]. However, in chronic HF, patients develop “natriuretic peptide resistance,” in which ANP and BNP are elevated but their renal and vascular effects are blunted [24]. This loss of counter-regulatory function allows RAAS and AVP to remain dominant, favoring ongoing fluid retention and hyponatremia despite high circulating peptide levels [25].

Additional factors perpetuate hyponatremia in HF. Chronic loop diuretic therapy increases distal sodium delivery, promoting further sodium loss while water retention persists under AVP influence [26]. Reduced renal perfusion from the cardiorenal syndrome further impairs the kidney’s ability to excrete free water. Inflammatory cytokines and oxidative stress further alter tubular function, worsening water balance [19]. Moreover, malnutrition, cachexia, and low solute intake, often seen in advanced HF, can not only reduce sodium intake but also decreased osmotic load impair free water excretion, compounding hyponatremia.

Mechanism of hyponatremia impact of in-hospital outcomes

Hyponatremia in HF is a signal of a sicker phenotype, such as those with greater congestion, lower forward flow, and renal vulnerability, and this composite risk profile explains the cascade of worse in-hospital outcomes we observed. The same fluid excess that dilutes sodium also floods the lungs, driving hypoxia and a higher likelihood of mechanical ventilation [27]. When clinicians pursue decongestion, these patients often require higher diuretic doses. However, because their effective intravascular volume is already depleted due to extravascular pooling, aggressive diuresis further reduces preload and exacerbates hemodynamic instability. Many are essentially in or on the verge of cardiogenic shock, and this imbalance necessitates escalation to inotropic support to maintain perfusion [28]. In patients with marginal cardiac output, persistent low-flow physiology and rising filling pressures often demand mechanical circulatory support, with intra-aortic balloon pump therapy used to reduce afterload and improve coronary perfusion, and ECMO deployed in extreme cases to provide both cardiac and respiratory support as a bridge to recovery or decision [29,30].

Congestion simultaneously leads to a reduced renal perfusion, leading to acute kidney injury, which then worsens fluid retention and clinical instability [6,31]. Hyponatremia also complicates inpatient management as sodium correction must be slow to avoid neurologic harm, prompting intensive monitoring, more labs, and delayed discharge [32]. These clinical and logistical factors lengthen length of stay and inflate charges through prolonged ICU/step-down care and device-based therapies [33]. Finally, the combination of severe congestion, metabolic stress, and treatment-related electrolyte shifts raises the risk of cardiac arrest and mortality [34,35]. Even though, in our cohort, the arrhythmia signal itself was modest, underscoring that the dominant pathway is global hemodynamic decompensation rather than isolated electrophysiologic toxicity. In short, hyponatremia flags patients who are harder to stabilize, more resource-intensive, and more prone to adverse events, thereby linking a simple lab value to a complex, costly hospital course.

Evidence from existing literature

Our findings align with prior literature describing hyponatremia as a predictor of higher mortality, such as that concluded by a meta-analysis conducted by Zhao et al. in 2023[36]. Similarly, Baser et al., through a study found an impact of hyponatremia on hospital length of stay [37]. On the contrary, a clinical trial by Cavusoglu et al., in 2019 found 177% higher risk of arrythmia in hyponatremia group [38]. There is no existing literature studying the impact of hyponatremia on total hospital charges, AKI, need for assist devices, cardiogenic shock or cardiac arrest.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of our study is the use of a large, nationally representative dataset, which enhances the generalizability of our findings to hospitalized HF patients across the United States. In addition, the use of propensity score matching reduced baseline imbalances and strengthened the validity of our comparisons. Some limitations also merit acknowledgment. As a retrospective analysis, the study is subject to unmeasured confounding, and reliance on ICD-10 codes may introduce misclassification of HF or hyponatremia. Serum sodium levels were captured categorically, preventing stratification by severity or trajectory of correction, which may have prognostic implications. Our dataset included only inpatient outcomes, and we could not assess post-discharge mortality or readmissions. Finally, variations in hospital practice patterns may influence management and outcomes. Despite these limitations, the consistency of associations across multiple endpoints supports the robustness of our findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, hyponatremia in HF is a simple but powerful clinical marker that identifies patients with advanced disease and a high-risk profile. Our study demonstrates that hyponatremia is associated with increased in-hospital outcomes such as mortality, prolonged hospitalization, greater complications, and higher healthcare costs, as well as greater reliance on intensive support measures. These findings underscore the importance of recognizing hyponatremia not as an isolated electrolyte abnormality, but as a signal of systemic instability and adverse prognosis. Early recognition and proactive management of hyponatremic HF patients may help guide closer monitoring, optimize therapeutic strategies, and improve both clinical and economic outcomes.

Acknowledgement

None to declare.

Source of Funding

The authors involved in the formulation of this manuscript have not received any form of financial support from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

References

2. Xia YM, Wang S, Wu WD, Liang JF. Association between serum sodium level trajectories and survival in patients with heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2023 Feb;10(1):255–263.

3. Rao J, Ma Y, Long J, Tu Y, Guo Z. The combined impact of hyponatremia and hematocrit on the risk for 90-day readmission and death in patients with heart failure: dilutional hyponatremia versus depletional hyponatremia. Ann Saudi Med. 2023 Jan-Feb;43(1):17–24.

4. Zhao L, Zhao X, Zhuang X, Zhai M, Wang Y, Huang Yet al. Hyponatremia and lower normal serum sodium levels are associated with an increased risk of all-cause death in heart failure patients. Nurs Open. 2023 Jun;10(6):3799–809.

5. Christopoulou E, Liamis G, Naka K, Touloupis P, Gkartzonikas I, Florentin M. Hyponatremia in Patients with Heart Failure beyond the Neurohormonal Activation Associated with Reduced Cardiac Output: A Holistic Approach. Cardiology. 2022;147(5-6):507–20.

6. Caraba A, Iurciuc S, Munteanu A, Iurciuc M. Hyponatremia and Renal Venous Congestion in Heart Failure Patients. Dis Markers. 2021 Aug 12;2021:6499346.

7. Palazzuoli A, Ruocco G, Del Buono MG, Pavoncelli S, Delcuratolo E, Abbate A, et al. The role and application of current pharmacological management in patients with advanced heart failure. Heart Fail Rev. 2024 Mar;29(2):535–48.

8. Charaya K, Shchekochikhin D, Agadzhanyan A, Vashkevich M, Chashkina M, Kulikov V, et al. Impact of Dapagliflozin Treatment on Serum Sodium Concentrations in Acute Heart Failure. Cardiorenal Med. 2023;13(1):101–8.

9. Herrmann JJ, Beckers-Wesche F, Baltussen LEHJM, Verdijk MHI, Bellersen L, Brunner-la Rocca HP, et al. Fluid REStriction in Heart Failure vs Liberal Fluid UPtake: Rationale and Design of the Randomized FRESH-UP Study. J Card Fail. 2022 Oct;28(10):1522–30.

10. Kapłon-Cieślicka A, Benson L, Chioncel O, Crespo-Leiro MG, Coats AJS, Anker SD, et al; on behalf of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the ESC Heart Failure Long-Term Registry Investigators. Hyponatraemia and changes in natraemia during hospitalization for acute heart failure and associations with in-hospital and long-term outcomes - from the ESC-HFA EORP Heart Failure Long-Term Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2023 Sep;25(9):1571–83.

11. Wei D, Chen S, Xiao D, Chen R, Meng Y. Positive association between sodium-to-chloride ratio and in-hospital mortality of acute heart failure. Sci Rep. 2024 Apr 3;14(1):7846.

12. Al Yaqoubi IH, Al-Maqbali JS, Al Farsi AA, Al Jabri RK, Khan SA, Al Alawi AM. Prevalence of hyponatremia among medically hospitalized patients and associated outcomes: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Saudi Med. 2024 Sep-Oct;44(5):339–48.

13. Fu S, Wang K, Ma X, Shi B, Ye C, Yan R, et al. Impact of hypotonic hyponatremia on outcomes in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement: a national inpatient sample. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2025 Mar 10;25(1):168.

14. Sarastri Y, Zebua JI, Lubis PN, Zahra F, Lubis AC. Admission hyponatraemia as heart failure events predictor in patients with acute heart failure. ESC Heart Fail. 2023 Oct;10(5):2966–72.

15. Vicent L, Alvarez-Garcia J, Gonzalez-Juanatey JR, Rivera M, Segovia J, Worner F, et al. Prognostic impact of hyponatraemia and hypernatraemia at admission and discharge in heart failure patients with preserved, mid-range and reduced ejection fraction. Intern Med J. 2021 Jun;51(6):930–8.

16. Thuluvath PJ, Alukal JJ, Zhang T. Impact of Hyponatremia on Morbidity, Mortality, and Resource Utilization in Portal Hypertensive Ascites: A Nationwide Analysis. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2022 May-Jun;12(3):871–5.

17. Cordova Sanchez A, Bhuta K, Shmorgon G, Angeloni N, Murphy R, Chaudhuri D. The association of hyponatremia and clinical outcomes in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a cross-sectional study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2022 Jun 18;22(1):276.

18. Ternero-Vega JE, Jiménez-de-Juan C, Castilla-Yelamo J, Cantón-Habas V, Sánchez-Ruiz-Granados E, Barón-Ramos MÁ, et al. Impact of hyponatremia in patients hospitalized in Internal Medicine units: Hyponatremia in Internal Medicine units. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024 May 24;103(21):e38312.

19. Pliquett RU, Schlump K, Wienke A, Bartling B, Noutsias M, Tamm A, et al. Diabetes prevalence and outcomes in hospitalized cardiorenal-syndrome patients with and without hyponatremia. BMC Nephrol. 2020 Sep 10;21(1):393.

20. Li N, Ying Y, Yang B. Aquaporins in Edema. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2023;1398:281–7.

21. Iovino M, Lisco G, Giagulli VA, Vanacore A, Pesce A, Guastamacchia E, et al. Angiotensin II-Vasopressin Interactions in The Regulation of Cardiovascular Functions. Evidence for an Impaired Hormonal Sympathetic Reflex in Hypertension and Congestive Heart Failure. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2021;21(10):1830–44.

22. Nouhravesh N, Gunn AH, Cyr D, Hernandez AF, Morrow DA, Velazquez EJ, et al. Sacubitril/valsartan versus valsartan initiation in patients naïve to renin-angiotensin system inhibitors: Insights from PARAGLIDE-HF. Eur J Heart Fail. 2025 Aug;27(8):1418–25.

23. Takeuchi S, Kohno T, Goda A, Shiraishi Y, Kitamura M, Nagatomo Y, et al; West Tokyo Heart Failure Registry Investigators. Renin-angiotensin system inhibitors for patients with mild or moderate chronic kidney disease and heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved ejection fraction. Int J Cardiol. 2024 Aug 15;409:132190.

24. Tsutsui H, Albert NM, Coats AJS, Anker SD, Bayes-Genis A, Butler J, et al. Natriuretic Peptides: Role in the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure: A Scientific Statement From the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America and Japanese Heart Failure Society. J Card Fail. 2023 May;29(5):787–804.

25. Gong H, Zhou Y, Huang Y, Liao S, Wang Q. Construction of risk prediction model for hyponatremia in patients with acute decompensated heart failure. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2023 Oct 26;23(1):520.

26. Wilcox CS, Testani JM, Pitt B. Pathophysiology of Diuretic Resistance and Its Implications for the Management of Chronic Heart Failure. Hypertension. 2020 Oct;76(4):1045–54.

27. Abassi Z, Khoury EE, Karram T, Aronson D. Edema formation in congestive heart failure and the underlying mechanisms. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022 Sep 27;9:933215.

28. Abraham J, Blumer V, Burkhoff D, Pahuja M, Sinha SS, Rosner C, et al. Heart Failure-Related Cardiogenic Shock: Pathophysiology, Evaluation and Management Considerations: Review of Heart Failure-Related Cardiogenic Shock. J Card Fail. 2021 Oct;27(10):1126–40.

29. Frigerio M. Left Ventricular Assist Device. Heart Fail Clin. 2021 Oct;17(4):619–34.

30. Malik A, Basu T, VanAken G, Aggarwal V, Lee R, Abdul-Aziz A, et al. National Trends for Temporary Mechanical Circulatory Support Utilization in Patients With Cardiogenic Shock From Decompensated Chronic Heart Failure: Incidence, Predictors, Outcomes, and Cost. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2023 Dec 4;2(6Part B):101177.

31. Asbagh AG, Sadeghi MT, Ramazanilar P, Nateghian H. Worsening renal function in hospitalized patients with systolic heart failure: prevalence and risk factors. ESC Heart Fail. 2023 Oct;10(5):2837–42.

32. Sterns RH, Rondon-Berrios H, Adrogué HJ, Berl T, Burst V, Cohen DM, et al; PRONATREOUS Investigators. Treatment Guidelines for Hyponatremia: Stay the Course. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2024 Jan 1;19(1):129–35.

33. Roe T, Brown M, Watson AJR, Panait BA, Potdar N, Sadik A, et al. Intensive Care Management of Severe Hyponatraemia-An Observational Study. Medicina (Kaunas). 2024 Aug 29;60(9):1412.

34. Mumbulu ET, Nkodila AN, Saint-Joy V, Moussinga N, Makulo JR, Buila NB. Survival and predictors of mortality in patients with heart failure in the cardiology department of the Center Hospitalier Basse Terre in Guadeloupe: historical cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024 Oct 28;24(1):599.

35. Shida H, Matsuyama T, Komukai S, Irisawa T, Yamada T, Yoshiya K, et al; CRITICAL Study Group Investigators. Early prognostic impact of serum sodium level among out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients: a nationwide multicentre observational study in Japan (the JAAM-OHCA registry). Heart Vessels. 2022 Jul;37(7):1255–64.

36. Zhao W, Qin J, Lu G, Wang Y, Qiao L, Li Y. Association between hyponatremia and adverse clinical outcomes of heart failure: current evidence based on a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2023 Dec 22;10:1339203.

37. Baser S, Yılmaz CN, Gemcioglu E. Do the etiology of hyponatremia and serum sodium levels affect the length of hospital stay in geriatric patients with hyponatremia? J Med Biochem. 2022 Feb 2;41(1):40–6.

38. Cavusoglu Y, Kaya H, Eraslan S, Yilmaz MB. Hyponatremia is associated with occurrence of atrial fibrillation in outpatients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. Hellenic J Cardiol. 2019 Mar-Apr;60(2):117–21.