Abstract

We present a case of late-onset eye manifestations in a Chinese girl of 18 years old with sporadic BS, presenting only mild eye inflammation. We performed comprehensive ocular examinations including fluorescein fundus angiography (FFA) and indocyanine green angiography (ICG) for her. The oral hormone plus local anti-inflammatory eye drops have well controlled the inflammation of her eyes.

Keywords

Blau syndrome, Late-onset eye manifestations, Panuveitis, Case report

Introduction

Blau syndrome (BS) is a rare, autosomal dominant, and granulomatous autoinflammatory disease first described by Blau in 1985 [1,2]. This syndrome is caused by mutation of the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2(NOD2)/ caspase activation and recruitment domain member 15 (CARD15) gene [3] and classically presents as a triad of granulomatous dermatitis, arthritis, and uveitis [4]. It typically begins at the age of 3–4 years. Initial symptoms are cutaneous and articular, while eye symptoms usually start later, between 7 and 12 years of age. Ophthalmic manifestations are characterized bilateral uveitis that begins as granulomatous iridocyclitis and posterior uveitis, resulting in panuveitis [5]. Eye involvement is usually the most relevant morbidity of BS.

Here, we report a case of an 18-year-old girl with only mild ocular inflammation who was initially diagnosed with suspected Blau syndrome for 15 years until her eye symptoms appeared at the age of 18 years old.

Case Reports

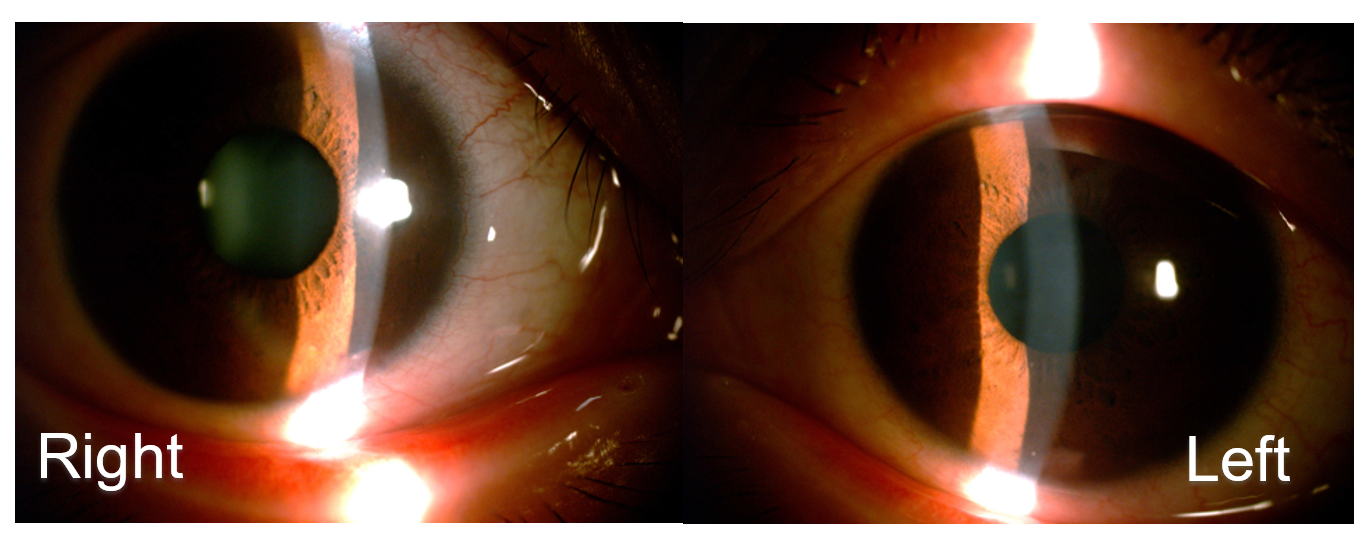

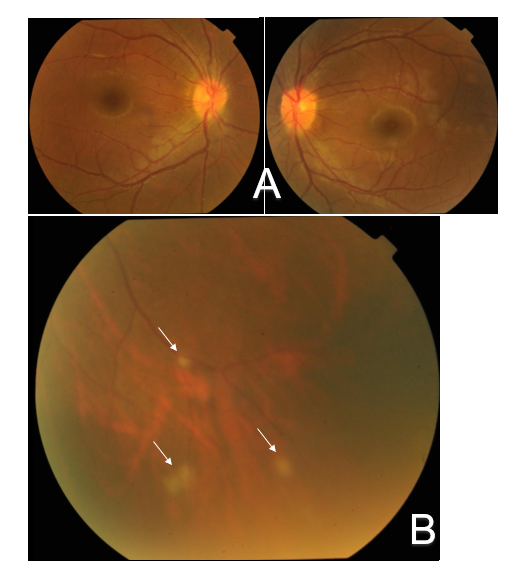

An 18-year-old Chinese girl presented at our hospital with sore eyes, photophobia and blurred vision. Ocular preliminary examinations in our department revealed best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) of 20/20 in the patient's both eyes. Anterior segment findings only included mild conjunctival hyperemia, mutton-fat keratic precipitates and slight aqueous flare in the anterior chamber in her both eyes (Figure 1), while fundus examinations revealed only optic disc hyperemia in both eyes and focal punctate retinal infiltrations in the inferior peripheral retina of the left eye (Figure 2) After a detailed medical history inquiry, we knew that she had been suffered from recurrent ankle and wrists swelling since she was 3 years old without any family history. Skin manifestations were not apparent except only roughness located on the trunk and forearms. Her past blood examinations showed only an elevated C-reactive protein level of more than 20 mg/dL (normal: less than 0.2 mg/dL). Between the ages of 3 and 6, the patient just had two fevers, each accompanied by joints swelling and pain involving wrists, right ankle and proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joints of feet. Methotrexate and prednisolone have been tried, and prednisolone was the most effective for her, so she has been taking it till now, at a dose of 5 mg daily at present.

Figure 1: Slit lamp photography demonstrates mild conjunctival hyperemia, mutton-fat keratic precipitates and slight aqueous flare in anterior segment in both eyes.

Figure 2: Fundus photographs show optic disc hyperemia in both eyes (A) and significant focal punctate infiltrations (arrows) in the inferior peripheral retina of the left eye (B).

A synovial biopsy of her right ankle showed chronic synovitis with noncaseating granulomas at her age of 6. Until then, pediatric rheumatologists had been unable to give her a definitive diagnosis. Since then, she has never had fevers, and the only joint swelling left is on her right ankle and right wrist (Figure 3). Genetic analysis revealed Met491Leu variant in the NOD2 gene, but how it caused the disease is unclear.

Figure 3: These pictures show the joint swellings left on her right ankle and right wrist at present.

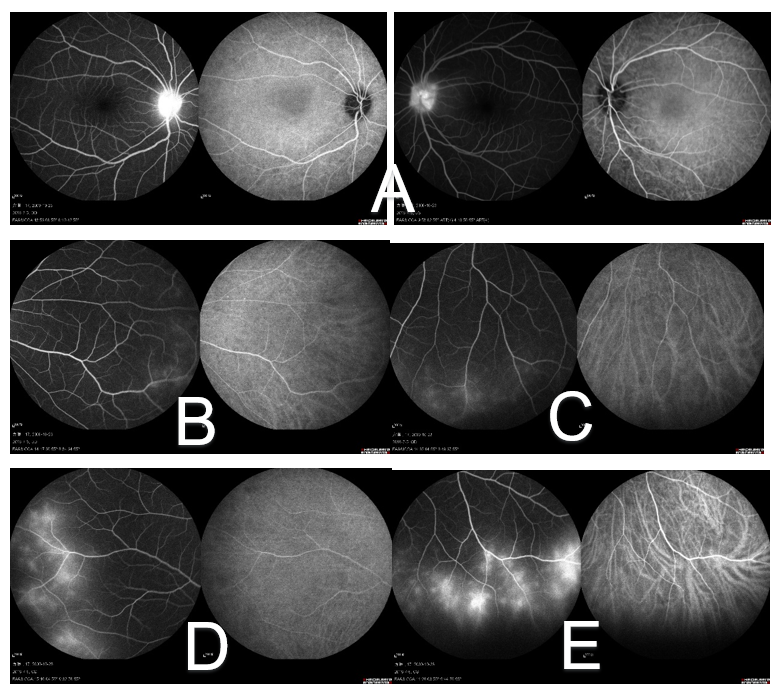

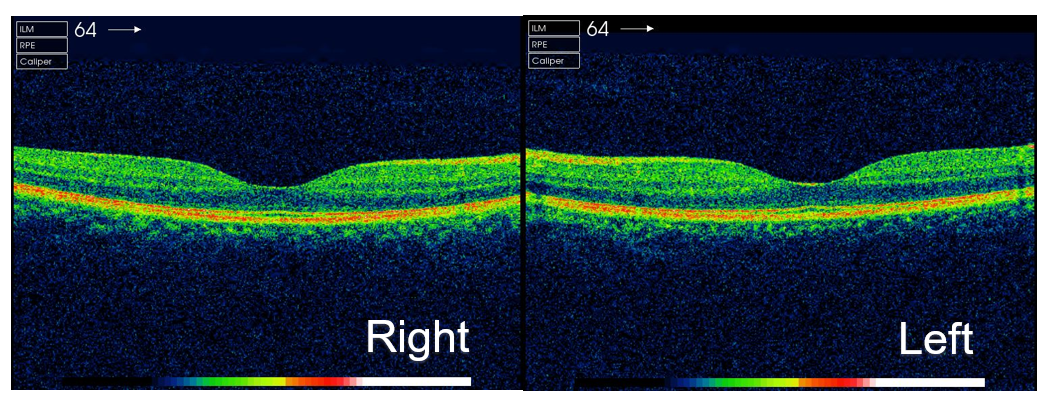

The appearance of ocular symptoms this time, accompanied by arthritis and skin lesions led to a preliminary diagnosis of Blau syndrome for her. Since she was older and could cooperate well with the examination, we conducted a further fluorescein fundus angiography (FFA) and indocyanine green angiography (ICG) for her which showed retinal vascular leakage in the nasal, inferior, and temporal retina of her right eye and inferior of the left, as well as hyper fluorescence in both optic discs (Figure 4). No obvious abnormality was found in optical coherence tomography of macula (Figure 5). Topical dexamethasone and compound tropicamide eye drops were used and controlled the inflammation. In the two years we observed, no serious ocular complications such as cataract or retinal detachment occurred.

Figure 4: FFA and ICG demonstrate vessel attenuation and optic disc hyperfluorescence (A) in early phase of both eyes, while late phase show peripheral leakage in the nasal (B), inferior (C) and temporal (D) retina of her right eye and inferior of the left. (E) The leakage in the left inferior retina is the most serious, which is consistent with the result of fundus photography.

Figure 5: OCT shows macula is normal in both eyes.

Discussion

It is sometimes a little difficult to reach a definite diagnosis of BS. Ocular manifestations play an important role in the diagnosis of BS. Okafuji et al. demonstrated that ocular lesions were seen in 18 of 20 patients with EOS(SBS)/BS [6]. The reasons for the difficulty in the diagnosis of this patient maybe the late onset of ocular complications. In a study by Takeuchi et al., it was reported that the median ages at uveitis onset were 24 months and 4.5 years [6], while Wouters’s research suggested that eye symptoms generally appear at around age 12 [7]. The ocular involvement in this patient occurred at her 18th year. This has a big impact on her diagnosis of the disease.

Eye involvement is usually the most relevant morbidity of BS. The most frequent clinical manifestation was anterior segment involvement with a proportion of 99% [8]. Meanwhile, a potential evolution can be seen into severe panuveitis which may lead to a cataract and band keratopathy, frequently requiring surgery [9]. Marín-Noriega has reported a 5-year-old boy of BS with bilateral cataracts and retinal detachment in his right eye. Despite the surgical treatment, his best-corrected visual acuity was no light perception in the right eye and 20/40 in the left [10]. The ocular involvement in our patient presented as an insidious granulomatous iridocyclitis, only shown as bilateral uveitis and focal punctate retinal infiltration in the fundus. A combination of topical steroid drops has controlled the low-level inflammation without serious ocular complications occurring so far, which may be related to the late onset of ocular symptoms so that the patient can find abnormalities more quickly, seek medical treatment in time and better cooperate with the treatment. However, because of this, doctors may be more likely to ignore the relationship between eye problems and systemic diseases.

In conclusion, we report a case of late-onset eye lesions in an 18-year-old girl of BS. Timely detection of eye abnormalities and presenting to the hospital, as well as better cooperation with comprehensive examination and medical treatment are easier for this relatively older patient, which may lead to better control of her eye lesions. At the same time, the clinical presentation of this patient highlights the necessity of systemic medical history inquiry in the clinical consultation work. The ophthalmologist must maintain a high degree of suspicion for the diagnosis of Blau syndrome in the clinical work, despite its relative rarity.

Abbreviations

BS: Blau syndrome; NOD2: Nucleotide-binding Oligomerization Domain containing 2; CARD15: Caspase Activation and Recruitment Domain member 15; FFA: Fluorescein Fundus Angiography; ICG: Indocyanine Green angiography; OCT: Optical Coherence Tomography

Consent for Publication

The written informed consent to publish this information was obtained from study participants and the proof of consent can be requested at any time.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

2. Tromp G, Kuivaniemi H, Raphael S, Ala-Kokko L, Christiano A, Considine E, et al. Genetic linkage of familial granulomatous inflammatory arthritis, skin rash, and uveitis to chromosome 16. Am J Hum Genet. 1996 Nov;59(5):1097-107.

3. Sfriso P, Caso F, Tognon S, Galozzi P, Gava A, Punzi L. Blau syndrome, clinical and genetic aspects. Autoimmun Rev. 2012 Nov;12(1):44-51.

4. Rosé CD, Wouters CH, Meiorin S, Doyle TM, Davey MP, Rosenbaum JT, et al. Pediatric granulomatous arthritis: an international registry. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Oct;54(10):3337-44.

5. Sfriso P, Caso F, Tognon S, Galozzi P, Gava A, Punzi L. Blau syndrome, clinical and genetic aspects. Autoimmun Rev. 2012 Nov;12(1):44-51.

6. Okafuji I, Nishikomori R, Kanazawa N, Kambe N, Fujisawa A, Yamazaki S, et al. Role of the NOD2 genotype in the clinical phenotype of Blau syndrome and early-onset sarcoidosis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009 Jan;60(1):242-50.

7. Wouters CH, Maes A, Foley KP, Bertin J, Rose CD. Blau syndrome, the prototypic auto-inflammatory granulomatous disease. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2014 Aug 6;12:33.

8. Sarens IL, Casteels I, Anton J, Bader-Meunier B, Brissaud P, Chédeville G, et al. Blau Syndrome-Associated Uveitis: Preliminary Results From an International Prospective Interventional Case Series. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018 Mar;187:158-166.

9. Kurokawa T, Kikuchi T, Ohta K, Imai H, Yoshimura N. Ocular manifestations in Blau syndrome associated with a CARD15/Nod2 mutation. Ophthalmology. 2003 Oct;110(10):2040-4.

10. Marín-Noriega MA, Muñoz-Ortiz J, Mosquera C, de-la-Torre A. Ophthalmological treatment of early-onset sarcoidosis/Blau syndrome in a Colombian child: A case report. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2020 Apr 18;18:100714.