Abstract

Introduction: Breast reconstruction has superior post-operative quality of life (QoL) outcomes compared to mastectomy. During the COVID-19 pandemic, however, breast reconstruction services across the UK were restricted. In Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, breast reconstruction was unavailable from March to September 2020. The aims of this study were to determine how many patients were affected and how this restriction has impacted the physical, psychosocial, and sexual wellbeing of these patients.

Materials & Methods: Patients who underwent mastectomy or breast reconstruction surgery in Aberdeen Royal Infirmary from 18th September 2019 to 18th September 2020 were identified from admissions lists. Breast Q questionnaires were administered via post to all eligible individuals. Participants were asked if they would have preferred reconstruction had it been offered. QoL scores were compared between 2 groups; 1) patients who underwent breast reconstruction prior to restriction of services and 2) patients who were not offered but would have preferred reconstruction. Data analysis was carried out using SPSS statistical software.

Results: 164 patients underwent procedures during the period, of which 147 were eligible to participate. 105/147 (71.4%) completed questionnaires were returned. Of those who had a procedure post-COVID restrictions, 15 (27.8%) stated they would have preferred reconstruction had it been offered. Lower QoL scores were observed in group 2 compared to group 1 in both psychosocial wellbeing (medians 49 and 63 respectively, p=0.022) and sexual wellbeing (medians 37.5 and 51.5 respectively, p=0.026).

Conclusions: Loss of breast reconstruction services affected 27.8% of patients. We demonstrate the negative impact this had on psychosocial and sexual wellbeing, which provides key information on impact of loss of resources from this service to aid balanced decision-making regarding service provision in the future.

Keywords

Breast cancer, Breast reconstruction, Patient reported outcome measures, COVID-19, Breast surgery

Introduction

Surgery is still one of the key components of Breast Cancer treatment. Even with the advancement in treatment options and surgical techniques, at least 35% of patients still undergo mastectomy, with a recent trend showing increasing rates of mastectomy [1]. Immediate Breast Reconstruction (IBR) has been shown to have a more favourable impact on quality of life when compared with mastectomy alone in the surgical management of women with breast cancer, without causing significant delays to adjuvant treatments. This positive effect can be seen across physical, emotional, and psychological outcomes [2,3]. It is therefore not surprising that up until the recent COVID-19 pandemic, trends showed an increasing use of breast reconstructive surgery [4].

The COVID-19 pandemic created a worldwide crisis in healthcare. In the UK, there was significant disruption to NHS services from routine care of chronic diseases and elective surgery to screening for diseases such as breast cancer. This has already been seen to have had a negative impact through reduction in cancer detection following disruption to screening services [5]. In addition to this, large numbers of elective procedures were cancelled or postponed [6]. Many breast services were moved offsite to be able to continue cancer service delivery and breast reconstruction was stopped at least for few months to enable the health services to deal with the pandemic [7,8]. Concerns are mounting regarding the long-term adverse effects this may have on patients and the growing backlog of care [9].

In the Breast Surgery Unit at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, breast reconstruction services were unavailable from 16th March 2020 until September 2020. This resulted in breast cancer patients not being offered IBR during this time period. This was in line with guidelines released during the COVID-19 pandemic by the American College of Surgeons, the European Society for Medical Oncology and the Association of Breast Surgery [10-12]. Though many other units resumed reconstructive services in late May early June, other services couldn’t because of the pressure on the hospital. The aims of this study were to determine how many patients were affected by restrictions locally and whether this restriction has impacted patients’ physical, psychosocial, and sexual wellbeing.

Materials and Methods

Patient identification and questionnaire administration

Patients who underwent mastectomy or breast reconstruction surgery between the 18th September 2019 to 18th September 2020, as identified from admissions lists of the Breast Surgery Unit, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, were eligible for the study. The first six months of the study period was the time immediately before the COVID-19 pandemic, when all reconstructive options were available, while the second six-month period saw the restriction of services with no reconstruction offered to patients.

Breast Q questionnaires were used, which provide outcome scores across several quality-of-life domains including; physical, psychosocial, and sexual wellbeing and post-operative satisfaction with breasts. Scores ranging from 0-100 are produced for each independent domain by calculating the sum of response scores for each individual domain which are then converted into RASCH scores using published conversion tables. RASCH scores express raw scale scores on a linear scale to allow comparison and evaluation [13]. Questionnaires were administered via post to all eligible individuals alongside a participant information sheet and postage-paid envelope for return. All documentation was anonymised using study ID number and no identifiable information was available on the returned questionnaire to maintain anonymity. Participation was voluntary and participant consent was indicated by return of the questionnaire. Patients who underwent surgery following restriction of breast reconstruction services were also asked if they would have considered reconstruction had it been offered to them. The study was registered with the local quality improvement and assurance team (Project ID 5170).

Data analysis

Mann-Whitney test was used to compare median RASCH scores for each quality-of-life domain between the two groups; 1) patients who underwent breast reconstruction prior to restriction of services and 2) patients who were not offered reconstruction but stated they would have considered reconstruction.

During analysis, pre-COVID-19 was defined as those who underwent procedures prior to 16th March 2020, the time after which the restrictions on services were implemented.

As per guidance for Breast Q questionnaire scoring in the context of missing data, if missing data was less than 50% of the domain’s items, the mean of the completed items was used. If more than 50% of the domain’s items were missing, data for the entire domain was classified as missing.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS v.26.0 (IBM Corp., USA). A p value of <0.05 was deemed to be statistically significant.

Results

A total of 164 patients underwent mastectomy +/- breast reconstruction during the period of the study. Of these, 147 were invited to participate, while the remaining 17 were uncontactable. 107 questionnaires were returned, of which two were not completed. Therefore 105/147 (71.4%) completed questionnaires were returned. In a proportion of these, the responses for particular domains were incomplete with less than 50% of items completed in that domain and were therefore classified as missing including; sexual wellbeing domain (n=16), psychosocial wellbeing (n=1) and satisfaction with breasts (n=1).

A total of 51 (48.6%) questionnaires returned were from participants who underwent a procedure prior to implementation of COVID-19 restrictions on services and 54 (51.4%) from those who underwent a procedure post-COVID-19 restrictions. A summary of the questionnaires returned by type and timing of procedure is shown in Table 1.

|

|

Pre-COVID Restrictions |

Post-COVID Restrictions |

|

Total Responses |

51 (48.6) |

54 (51.4) |

|

|

|

|

|

Type of Procedure: |

|

|

|

Mastectomy |

31 (60.8) |

54 (100) |

|

Reconstruction |

20 (39.2) |

0 (0) |

|

|

|

|

|

Age (years) |

57.3 ± 13.5 |

60.9 ± 12.4 |

|

Data are presented as n (%) or mean ± standard deviation. Data are presented as n (%) |

||

Patients affected by restriction of breast reconstruction services

Of the 164 procedures performed over the study time period, 78 (47.6%) were performed in the six months prior to implementation of COVID-19 restrictions and 86 (52.4%) were performed in the six months subsequent to this. Pre-COVID-19 restrictions, 25 (32%) patients underwent reconstruction. No reconstruction procedures were performed following COVID-19 restrictions implemented on 16th March 2020 (Table 2).

|

|

Pre-COVID Restrictions |

Post-COVID Restrictions |

|

Total No. Of Procedures |

78 (47.6) |

86 (52.4) |

|

|

|

|

|

Type of Procedure: |

|

|

|

Mastectomy |

53 (68) |

86 (100) |

|

Reconstruction |

25 (32) |

0 (0) |

Restriction of services and quality of life

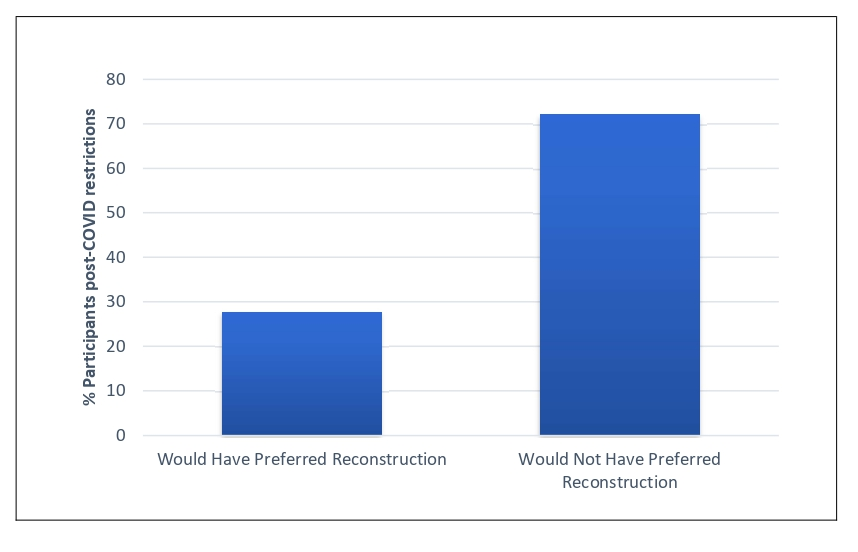

A total of 20 patients underwent breast reconstruction prior to restriction of services implemented due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Of those who had a procedure within the study time period post-COVID-19 restrictions, 15 (27.8%) stated they would have preferred reconstruction if it had been offered (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Comparison of percentage of all participants who underwent a procedure post-COVID restrictions who would have preferred reconstruction compared to those who would not have preferred reconstruction.

Comparison of median RASCH scores (Table 3) between groups 1) patients who underwent breast reconstruction prior to restriction of services and 2) patients who were not offered reconstruction but stated they would have preferred reconstruction, showed significantly lower scores in the psychosocial wellbeing domain in group 2 compared to group 1 (medians 49 (IQR 13.5) and 63 (IQR 12.3) respectively, p=0.022). Significantly lower scores were also observed in the sexual wellbeing domain in group 2 compared to group 1 (medians 33.5 (IQR 14) and 51.5 (IQR 27.3) respectively, p=0.026). No significant differences were observed in scores for physical wellbeing and post-operative satisfaction with breasts domains.

|

|

Reconstruction pre-COVID restrictions |

Reconstruction unavailable post-COVID restrictions but would have chosen reconstruction |

|

No. of Patients |

20 |

15 |

|

|

|

|

|

Age – y (mean ± SD) |

45.9 ± 6.8 |

55.4 ± 13.2 |

|

|

|

|

|

Quality of Life Outcome Scores: |

|

|

|

Physical wellbeing |

26 (12) |

32 (28) |

|

Psychosocial wellbeing * |

63 (12.3) |

49 (13.5) |

|

Sexual wellbeing ** |

51.5 (27.3) |

33.5 (14) |

|

Post-operative satisfaction with breasts |

55.5 (17) |

39 (21.5) |

|

Data are presented as n or median (interquartile range) unless otherwise stated. *p=0.022 **p=0.026 |

|

|

Discussion

Surgical services during the COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on healthcare services worldwide, in particular leading to a reduction in elective surgery capacity, with many elective procedures being cancelled or postponed. In Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, no breast reconstruction procedures were performed from 16th March to mid-September 2020 following implementation of restrictions due to COVID-19. The restriction in breast reconstruction services observed reflects national guidelines released during the COVID-19 pandemic from the American College of Surgeons and European Society for Medical Oncology, which categorised breast reconstructive surgery as low priority and advised deferring immediate reconstruction [10,11]. The Association of Breast Surgery guidance also advised prioritisation of patients were ER negative are HER2 positive and node positives the first priority followed by pre-menopausal, high risk ER positive, post-menopausal ER positive, large high grade DCIS and lately the remaining DCIS patients. In addition to stating that immediate and delayed reconstruction cases should not be offered in the majority of patients [12].

Interestingly, we show that there is a comparable number of procedures performed in the six months following the implementation of COVID-19 restrictions on services on 16th March 2020 compared to the preceding six months. This is due to forward planning, as the unit had protocols ready for the service to be mobilised offsite to allow maintenance of cancer services with prioritisation of cases according to guidelines [7].

Lack of patient choice, quality of life and implications for the future

Post-operative outcomes differ between the surgical options for breast cancer treatment, with mastectomy having previously been shown to result in poorer quality of life outcomes compared to reconstructive surgery [2]. This study demonstrates that 27.8% of patients undergoing breast cancer surgery in the time period during the COVID-19 restrictions would have preferred breast reconstruction and were therefore negatively impacted by the restrictions causing this service to be unavailable. In addition, the negative impact this has had on quality of life is demonstrated by the lower quality of life scores seen for both psychosocial and sexual wellbeing in affected patients. Although delayed reconstruction remains an option for these patients, this has also been shown to result in poorer psychosocial wellbeing outcomes compared to immediate reconstructive surgery [14].

The treatment option chosen by patients can be related to both patient factors and the counselling received pre-operatively [15]. Patient choice and involvement in treatment decisions has been demonstrated to be a key factor in the approach to breast cancer management [16]. The restrictions applied to Breast Surgery Units during the COVID-19 pandemic represents not only restriction of the surgical procedure in itself but also in patient choice and autonomy. The poorer psychosocial and sexual wellbeing observed in the women who were denied their choice of breast reconstruction surgery highlights the harm that restriction of both breast reconstruction services and patient choice has had on affected patients.

The COVID-19 pandemic represents an unprecedented time during which global prioritisation of healthcare resources was necessary to accommodate increasing demand. The National Health Service is now in the recovery phase and working to not only reinstate services, but tackle the overwhelming backlog of elective surgery waiting lists which are now longer than ever before [17]. However, the post-pandemic phase represents an opportunity to reflect and learn from the events of the pandemic in order to inform future prioritisation of services in the context of competing healthcare resource demand. With increasing emergence of new COVID-19 variants, in addition to winter pressures on hospitals, further decisions regarding service prioritisation may be essential in the near future. In order to make balanced decisions between competing service needs, an understanding of the impact that loss of resources has on outcomes for specific patient groups and services is necessary.

This study demonstrates the negative impact that loss of breast reconstruction services has had on patients who were denied this procedure during the previous wave of restrictions within the National Health Service. Calls were made during the pandemic to amend national guidance to reflect evidence of the importance of breast reconstructive surgery for patient wellbeing, while at the same time adopting a pragmatic approach that conserves resources and promotes patient and staff safety. [18]. Our results further support the importance of breast reconstructive surgery for patient quality of life in both psychosocial and sexual wellbeing domains. However, while we demonstrate the negative impact the restriction of services has had from the perspective of patient quality of life, this of course needs to be balanced with the benefit of re-allocation of resources elsewhere. It is recognised that one of the challenges in resource allocation is the weighing up of the needs of competing services and their subsequent beneficial and negative impacts on patient groups. This study does, however, provide insight into the impact of restriction of breast reconstruction services that this can aid the decision-making process with regards to allocation of services in the future.

Strengths and limitations

This study demonstrates patient reported outcomes across quality of life domains from a questionnaire validated for the specific patient group in this study, the Breast Q questionnaire. It has been used extensively to assess patient-reported outcomes following breast surgery, including in the national mastectomy and breast reconstruction audit (NMBRA), a national study investigating patient outcomes in breast cancer patients undergoing mastectomy, with or without breast reconstruction [2]. The high questionnaire return rate of 71.4% reflects the validity and reproducibility of the data produced. Despite this, the study presents data from a single Breast Surgery unit with small numbers and is therefore limited by its small scale compared to multi-centre studies.

This study represents only the immediate effect of service restriction on patient quality of life, however total cumulative cost both to patients and future breast surgery services, is yet to be determined. Future impact on quality of life needs to be assessed in order to determine whether the observed negative impact on quality of life is sustained or is resolved in the short-term. Answers to these questions, in addition to whether these patients go on to undergo delayed reconstruction, and whether this also subsequently impacts quality of life compared to IBR, are required to truly understand the long-term effects on both patient quality of life and breast reconstruction services. This represents further research needed as this data becomes available in the future.

Conclusion

The COVID-19-related loss of breast reconstruction services affected 27.8% of patients in our unit. We demonstrate the negative impact this had on the psychosocial and sexual wellbeing of these patients, providing insight into the effect of loss of resources from this specific service in order to aid balanced decision-making when weighing up competing service needs in future decisions regarding service provision.

Conflict of Interest

None Declared

Role of Funding

Funding was received from the NHS Grampian Endowment Fund to fund research time for the research nurses to contact the patients for the PROMS.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Local Clinical Effectiveness department and was registered with local quality improvement and assurance team (Project ID 5170).

References

2. RCS(Eng). National Mastectomy and Breast Reconstruction Audit. NMBR Audit Rep. 2009.

3. O’Connell RL, Rattay T, Dave R V, Trickey A, Skillman J, Barnes NLP, et al. The impact of immediate breast reconstruction on the time to delivery of adjuvant therapy: the iBRA-2 study. Br J Cancer. 2019 Apr;120(9):883-95.

4. Jonczyk MM, Jean J, Graham R, Chatterjee A. Surgical trends in breast cancer: a rise in novel operative treatment options over a 12 year analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;173(2):267-74.

5. Rutter MD, Brookes M, Lee TJ, Rogers P, Sharp L. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on UK endoscopic activity and cancer detection: a national endoscopy database analysis. Gut. 2021;70(3):537-43.

6. COVIDSurg Collaborative. Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID-19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. J Br Surg. 2020;107(11):1440-9.

7. Strickland J, Elsberger B, Lip G, Fuller M, Masannat Y. Impalpable Breast Cancer and Service Delivery During the COVID-19 Pandemic - the Role of Radiofrequency Tag localization. Arch Breast Cancer. 2021;8(3):247-50.

8. Dave R V, Kim B, Courtney A, O’Connell R, Rattay T, Taxiarchi VP, et al. Breast cancer management pathways during the COVID-19 pandemic: outcomes from the UK “Alert Level 4” phase of the B-MaP-C study. Br J Cancer. 2021 May;124(11):1785-94.

9. Søreide K, Hallet J, Matthews JB, Schnitzbauer AA, Line PD, Lai PBS, et al. Immediate and long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on delivery of surgical services. J Br Surg. 2020;107(10):1250-61.

10. Consortium CPBC. COVID‐19 guidelines for triage of breast cancer patients. Am Coll Surg. 2020.

11. de Azambuja E, Trapani D, Loibl S, Delaloge S, Senkus E, Criscitiello C, et al. ESMO Management and treatment adapted recommendations in the COVID-19 era: Breast Cancer. ESMO Open. 2020;5:e000793.

12. Surgery A of B. Association of Breast Surgery Statement, 27th April 2020. 2020.

13. Boone WJ. Rasch Analysis for Instrument Development: Why, When, and How? CBE Life Sci Educ. 2016;15(4).

14. Al-Ghazal SK, Sully L, Fallowfield L, Blamey RW. The psychological impact of immediate rather than delayed breast reconstruction. Eur J Surg Oncol J Eur Soc Surg Oncol Br Assoc Surg Oncol. 2000 Feb;26(1):17-9.

15. Pusic A, Thompson TA, Kerrigan CL, Sargeant R, Slezak S, Chang BW, et al. Surgical options for the early-stage breast cancer: factors associated with patient choice and postoperative quality of life. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;104(5):1325-33.

16. Molassiotis A. The importance of quality of life and patient choice in the treatment of breast cancer. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2004;8:S73-4.

17. Macdonald N, Clements C, Sobti A, Rossiter D, Unnithan A, Bosanquet N. Tackling the elective case backlog generated by Covid-19: the scale of the problem and solutions. J Public Health (Bangkok). 2020 Nov 23;42(4):712-6.

18. Kumar NG, Kung TA. Guidelines for breast reconstruction during the COVID‐19 pandemic: Are we considering enough evidence? Breast J. 2020.