Abstract

Objectives: This study evaluated the performance of NicAlert™ (Nymox Pharmaceutical Corporation) immunochromatographic strips for point-of-care (POC) nicotine testing of urine for pre-surgical qualification.

Methods: Performance was compared with liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) and enzyme immunoassay test (EIA) (Beckman Coulter AU5810). The predicted NicAlert™ reading and EIA results were calculated based on LC-MS/MS results and compared to measured results. The sensitivity and specificity were calculated.

Results: The NicAlert™ test strip had limited test performance (sensitivity=100%, specificity=40%) compared with EIA (sensitivity=100%, specificity=81%). In addition, the NicAlert™ tests had cross-reactivity to the metabolite, 3-OH-cotinine.

Conclusion: NicAlert™ test strips demonstrated high sensitivity for cotinine to assess recent tobacco exposure, due to the cross-reactivity with 3-OH-cotinine. This implies that recent nicotine exposure via passive, active, or chronic use, during the 6 weeks, will likely be detected by the NicAlert™ test strip.

Keywords

Cotinine, Nicotine, Point of care, Smoking, Pre-surgery qualification, Immunoassay, LC-MS/MS

Introduction

The health consequences of tobacco use continue to be a major concern in the United States [1] and the world [2]. Consequently, nicotine metabolite testing has expanded to include workplace testing, child custody cases, health insurance pre-qualification, pre-surgical organ transplant qualification, and smoking cessation programs. Nicotine use is also linked to poor surgical outcomes and studies have shown an increased risk for infection, increased morbidity, delayed wound healing, longer hospital stays, and postoperative respiratory failure [3]. In children, nicotine exposure can increase the risk of respiratory problems, before and after anesthesia [4-8]. Additionally, nicotine absorption from replacement therapy can increase nicotine metabolites in the blood and urine and may impact post-surgical outcomes. Therefore, patients may be required to abstain from both tobacco and nicotine replacement therapy before surgery.

The practice of nicotine cessation before elective surgery is still controversial. At some institutions, surgeons may require patients to abstain from all nicotine products for a period of up to 6 weeks before surgery or risk cancellation of the procedure [9]. This requires testing a urine specimen from patients on the morning of the planned surgery for the detection of nicotine and metabolites.

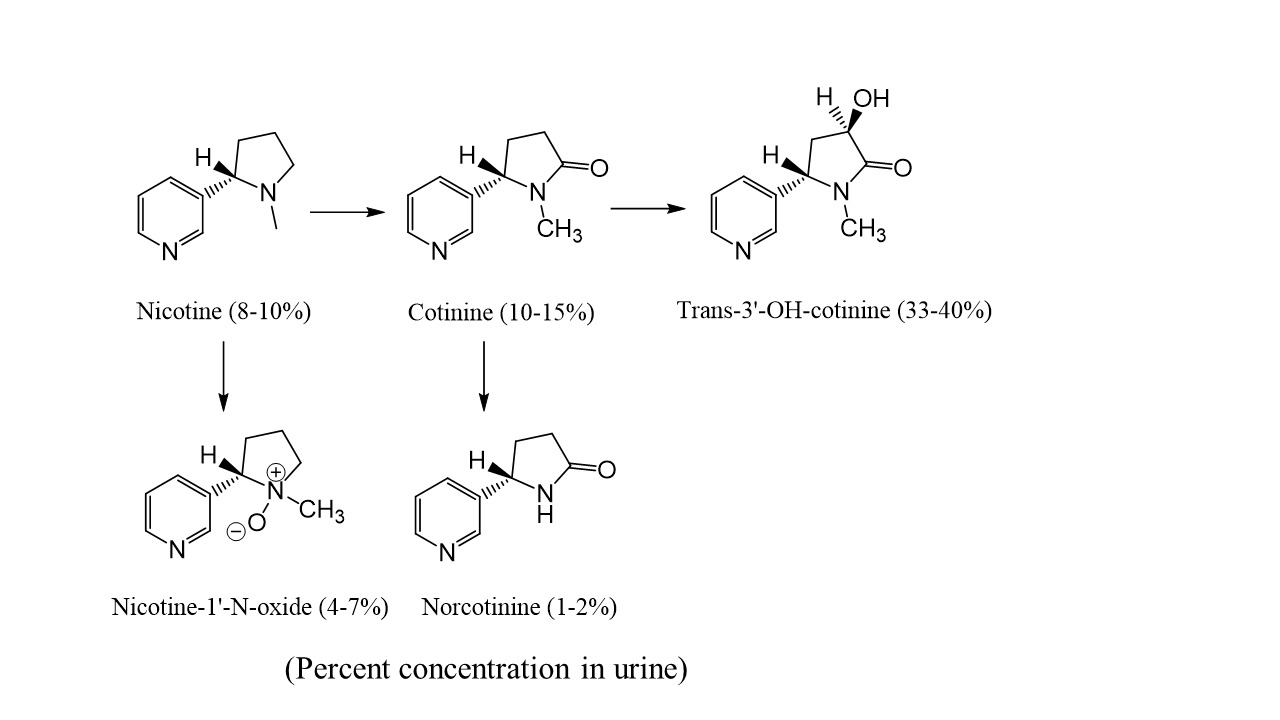

Nicotine has a short half-life (1-4 hours [10]) and therefore the compound itself has limited use for detecting tobacco or nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) exposure. Nicotine is also extensively metabolized (Figure 1) [11,12]. Approximately 3-5% of nicotine is converted to nicotine-glucuronide catalyzed by uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferases (UGT) [13]. The primary metabolite of nicotine is cotinine, which is highly specific for nicotine exposure and has a relatively long half-life (16-20 hours). This transformation is first mediated by the cytochrome P450 system and the second step to produce cotinine is catalyzed by aldehyde oxidase (AOX) [14]. Cotinine is further metabolized into trans-3’-hydroxycotinine (3-OH-cotinine) with a half-life of about 15 hours. Nicotine, cotinine, and metabolites also form glucuronide conjugates.

Figure 1: Nicotine metabolism.

The advantage of using urine as the specimen type to assess nicotine exposure is that the concentrations of cotinine are several-fold higher than in blood or oral fluid [15]. Due to the relatively high concentrations of cotinine and 3-OH-cotinine in urine, these metabolites are commonly targeted biomarkers for tobacco use, NRT, and passive exposures. Table 1 provides proposed urinary cut-offs to distinguish non-smokers from passive-active smokers [12,14,16,17].

|

Specimen |

Non-smokers |

Passive Exposure |

Active smokers |

|

Urine |

Nicotine: <2.0 ng/mL |

Nicotine: <20 ng/mL |

Nicotine: >30 ng/mL |

|

Cotinine: <5.0 ng/mL |

Cotinine: <20 ng/mL |

Cotinine: >100 ng/mL |

|

|

3-OH-Cotinine: <50 ng/mL |

3-OH-Cotinine: <50 ng/mL |

3-OH-Cotinine: >120 ng/mL |

|

|

Anabasine: <2.0 ng/mL |

Anabasine: <2.0 ng/mL |

Anabasine: >2 ng/mL |

Cotinine can be measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS), immunoassay, or point-of-care (POC) devices [18]. POC is an attractive alternative because it is often inexpensive and provides immediate results without additional instrumentation. Metabolites of nicotine are most accurately measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) but this technology is not common to hospitals or clinics, and samples are often required to be sent to a reference laboratory for analysis. While LC-MS/MS can have a low limit of detection, high sensitivity, and specificity, it also allows the detection and quantitation of nicotine, metabolites, and tobacco alkaloids (i.e. anabasine) in a single assay.

Conversely, this technology is often more expensive and has a greater turnaround time to result than POC or immunoassay testing. Measuring cotinine by laboratory-based immunoassay and/or POC immunoassay devices are available as alternative methods that can be performed quickly at the clinic or hospital. Immunoassay and POC methods for cotinine are sensitive; however, the results are usually not quantitative.

One of the available nicotine screening options is a POC device, NicAlert™ test strip. The test has a 15-minute turnaround time to result and has gained popularity due to its ability to rapidly discriminate between smokers from non-smokers. One of the issues with immunoassay and POC methods is the cross-reactivity of metabolites such as 3-OH-cotinine. 3-OH-cotinine can persist in long-term smokers and cause potential positive results in patients who have recently quit smoking. Positive results, due to cross-reactivity to nicotine metabolites can be differentiated with mass spectrometry methods or by testing patients after longer periods of abstinence > 2 weeks.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the performance of NicAlert™ (Nymox Pharmaceutical Corporation) POC immunochromatographic strips for clinical use in a University Hospital setting, to assess pre-surgical patients for nicotine cessation on the morning of surgery. The performance was compared with LC-MS/MS and enzyme immunoassay (EIA, Beckman Coulter AU5810).

Materials and Methods

Specimens

All specimen collection, deidentification, testing, and data processing were performed at the University of Utah affiliated ARUP Laboratories, with manuscript authors affiliated with the University of Utah at the time of the study. Using a University of Utah IRB approved protocol for samples used in clinical laboratory test development, forty-five urine residual samples were selected from the laboratory database that had previously been run on the nicotine and metabolites quantitative urine panel performed by LC-MS/MS at ARUP Laboratories. The urine samples were shipped to ARUP at ambient temperature or refrigerated (4°C) and were maintained in refrigerated storage after initial testing. There were 25 males and 20 females, and the age range was 16-73 years old. Nicotine concentrations ranged from 2 to 3460 ng/mL and metabolite concentration ranges (cotinine, 3-OH-cotine and nor cotinine) were from 2 ng/mL to greater than 5000 ng/mL. The 44 patient samples were evaluated on both the cotinine EIA and the NicAlert™ test strips.

In addition to the 44 patient samples, eleven negative urine samples were spiked with commercially available cotinine and 3-OH-cotinine to assess for potential cross-reactivity. One sample was spiked with 19.2 ng/mL cotinine, 3780 ng/mL 3-OH-cotinine, respectively. Additional urine samples were spiked with varying concentrations of 3-OH-cotinine (4320, 2260, 1120, 627, 339, 168, 68.7, 41.2, 19 and 10 ng/mL). The samples were evaluated by both EIA and the NicAlert test strips.

Mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) method

The mass spectrometry method and method validation data for the nicotine assay were published by Suh-Lailam et al. 2014 [19]. In brief, 500 µL of ammonium acetate buffer, pH 4.0, and 50 µL of a mixture of deuterated internal standards were added to 500 µL aliquots of each urine specimen. Solid-phase extraction was performed, followed by elution and evaporation under nitrogen gas at 50°C and reconstitution in 90% 20 mM ammonium bicarbonate, 10% acetonitrile solution. The analysis was performed on an LC-MS/MS system with PAL auto sampler (LEAP) with Agilent 1200 pumps, Phenomenex Gemini-NX C18 column (100 X 2 mm, 3 µm particles), and AB Sciex API 4000 mass spectrometer. The analyte panel quantifies nicotine, nor nicotine, cotinine, trans-3’-hydroxy-cotinine (3-OH-cotinine), and anabasine concentrations.

Auto-Lyte® Cotinine EIA

The specimens that were quantified by mass spectrometry (44 patient specimens and the 11 spiked samples) were assayed for cotinine by enzyme immunoassay (OraSure Technologies, Bethlehem, PA) on the Beckman Coulter AU5810 chemistry analyzer. The EIA cotinine method is qualitative, and results were reported as positive when the concentration was equal to or greater than 100 ng/mL. Results were reported as negative when the concentration was less than 100 ng/mL. The Auto-Lyte® Cotinine EIA has a limit of detection (LOD) of 100 ng/mL, to classify the result as a positive. The assay does not cross-react with niacinamide, nicotine, nicotinic acid, and nicotinic acid N-oxide at concentrations of 10,000 ng/mL. However, there is a 4.4% cross-reactivity to 3-OH-cotinine at 10,000 ng/mL.

NicAlert™ Test Strips

The samples analyzed by mass spectrometry were tested by the NicAlert™ test strips, according to the package insert. NicAlert™ test strips are semi-quantitative and utilize monoclonal antibodies, coated with gold particles on the sample application pad.

If cotinine is present in the urine specimen, the cotinine will bind to the gold particle conjugate to occupy the binding site, to provide quantitation by a series of avidity “traps”. The test strip has seven numbered zones (0-6); level 0 (0-10 ng/mL), level 1 (10-30 ng/mL), level 2 (30-100 ng/mL), level 3 (100-200 ng/mL), level 4 (200-500 ng/mL), level 5 (500-1000 ng/mL), and level 6 (>1000 ng/mL). According to the instructions of use, level 3 has a clinical sensitivity of 87% and specificity of 100% for identifying the current use of tobacco. LOD is not provided by the manufacturer. Levels 0-2 were interpreted as negative and levels 3 or greater were interpreted as positive and indicated recent tobacco use. The assay has 25% cross-reactivity to 3-OH-cotinine at concentrations between 125-2000 ng/mL and <1% cross-reactivity to nicotine at concentrations ranging from 2000-20,000 ng/mL.

Assay Cut-offs

The NicAlert™ and EIA results were evaluated based on the concentrations of cotinine measured by LC-MS/MS and then compared to the qualitative results by each method. A NicAlert™ test strip reading of 3 or greater was considered to be positive, with a cotinine concentration > 100 ng/mL. The sensitivity and specificity were calculated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs, using exact (Clopper-Pearson) method). As such, a positive result by EIA and mass spectrometry was set at a 100 ng/mL cut-off.

Results

Of the 44 urine samples tested (Table 2), the following ranges of concentrations for cotinine and 3-OH-cotinine (in parentheses) were obtained by LC-MS/MS:

- 9 samples with undetectable concentrations of all nicotine metabolites

- 10 samples with less than 50 ng/mL of cotinine (3-OH-cotinine ranged 50-91 ng/mL)

- 5 samples with 50-100 ng/mL of cotinine (3-OH-cotinine ranged 226-1240 ng/mL)

- 10 samples with 100-250 ng/mL of cotinine (3-OH cotinine ranged 113-2230 ng/mL)

- 10 samples with greater than 1000 ng/mL of cotinine (3-OH-cotinine ranged from 2030 to greater than 5000 ng/mL).

|

|

LC-MS/MS Result |

|

|

NicAlert™ Reading |

Cotinine >100 ng/mL |

Cotinine < 100 ng/mL |

|

Test Positive (3+) |

20 |

15* |

|

Test Negative (less than 3) |

0 |

9 |

Cotinine analysis by NicAlert™ Test Strip

Evaluation of specimens with cotinine results <100 ng/mL would indicate no current active nicotine use. Detection of cotinine below this cut-off is suggestive of abstinence for less than 2 weeks [14] or passive exposure [20]. Ten samples were correctly identified as negative with cotinine concentrations less than 100 ng/mL by mass spectrometry (Table 2). Twenty samples were correctly identified as positive by the NicAlert™ test strips with cotinine concentrations greater than 100 ng/mL by mass spectrometry. Fifteen results from the NicAlert test did not correlate to cotinine concentrations measured by mass spectrometry (Table 2). These samples had cotinine concentrations less than 100 ng/mL and 10 out of the 15 had 3-OH-cotinine concentrations <120 ng/mL. All the 15 samples were positive by the NicAlert™ test strips and had a result of 3 or greater (Table 3). One specimen did not have detectable concentrations of nicotine or metabolites by LC-MS/MS, but had a positive result by the NicAlert™ test strip (Table 3), suggesting an interfering substance presence that is not detected by the LC-MS/MS method. Overall, the sensitivity and specificity [95% confidence interval (CI)] for the NicAlert™ test strip was 100 % (83-100%) and 37.5% (19-59%), respectively.

|

Nicotine (ng/mL) |

Cotinine (ng/mL) |

3-OH-Cotinine (ng/mL) |

Nor-Nicotine (ng/mL) |

Anabasine (ng/mL) |

NicAlert™ # |

NicAlert™ Expected Result |

NicAlert™ Actual Result |

|

|

2 |

7 |

73 |

<2 |

<3 |

1 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

<2 |

8 |

91 |

<2 |

<3 |

1 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

<2 |

11 |

84 |

<2 |

<3 |

2 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

14 |

6 |

59 |

<2 |

<3 |

1 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

58 |

8 |

66 |

Pos |

<3 |

1 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

9 |

6 |

50 |

<2 |

<3 |

1 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

58 |

8 |

66 |

Pos |

<3 |

2 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

8 |

69 |

295 |

5 |

<3 |

2 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

<2 |

<5 |

<50 |

<2 |

<3 |

0 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

18 |

52 |

226 |

2 |

<3 |

2 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

14 |

6 |

59 |

<2 |

<3 |

0 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

14 |

6 |

59 |

<2 |

<3 |

0 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

404 |

95 |

1240 |

8 |

<3 |

2 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

18 |

52 |

226 |

2 |

<3 |

2 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

|

<2 |

53 |

328 |

<2 |

<3 |

2 |

Neg |

Pos |

|

Cotinine analysis by immunoassay

The EIA performed well in comparison to the cotinine results by LC-MS/MS. The EIA had 21 true positives, 21 true negatives, and 5 specimens that had cotinine concentrations less than 100 ng/mL; however these specimens screened positive due to the presence of 3-OH-cotinine which ranged from 226–1240 ng/mL. The immunoassay was found to be 100% sensitive (84-100%) and 81% specific (61-93%). The sample spiked with 19.2 ng/mL of cotinine and 3780 ng/mL of 3-OH-cotinine were positive by the NicAlert™ test strip (Table 4). For the additional urine samples spiked with 3-OH-cotinine, the 4320, 2260, 1120, 627, 339, and 168 ng/mL concentrations were positive by the NicAlert™ test strips. By EIA, only the 4320 and 2260 ng/ml were positive.

|

Mass Spectrometry Results |

NicAlert™ |

EIA |

||

|

Cotinine (ng/mL) |

3-OH Cotinine (ng/mL) |

NicAlert™ Reading |

Interpretation |

Interpretation |

|

19.2 |

3780 |

6 |

Pos |

Pos |

|

0 |

4320 |

6 |

Pos |

Pos |

|

0 |

2260 |

6 |

Pos |

Pos |

|

0 |

1120 |

6 |

Pos |

Neg |

|

0 |

627 |

6 |

Pos |

Neg |

|

0 |

339 |

5 |

Pos |

Neg |

|

0 |

168 |

3 |

Pos |

Neg |

|

0 |

68.7 |

2 |

Neg |

Neg |

|

0 |

41.2 |

2 |

Neg |

Neg |

|

0 |

19 |

1 |

Neg |

Neg |

|

0 |

10 |

1 |

Neg |

Neg |

Discussion

Nicotine metabolite testing is used to support several clinical and forensic applications. In this study, the NicAlert™ test strips were evaluated to be used as POC devices in a University Hospital setting for pre-surgical evaluation of nicotine cessation. Additional experiments were conducted to compare the NicAlert™ results with the presence of nicotine, cotinine, or 3-OH-cotinine measured by LC-MS/MS.

If any nicotine metabolite was present by LC-MS/MS then the NicAlert™ test result was predicted to be positive. In this analysis, there was only one false positive, which corresponded to 100% sensitivity and 90.9% specificity. The EIA performed well in comparison to the measured cotinine concentrations by LC-MS/MS. However, implementation of EIA platforms is limited to central testing facilities and is usually unavailable for patient bedside testing, thus limiting its applicability in pre-surgical nicotine screening demanding rapid availability of results.

The mix of samples from the patients in this study included a wide range of cotinine and 3-OH-cotinine concentrations to test the clinical specificity of the NicAlert™ and additional comparison to the cotinine EIA. 3-OH-cotinine is a known cross-reactant of the NicAlert™ test strips. The NicAlert™ package insert claims that 3-OH-cotinine showed 12-40% cross-reactivity with cotinine in their assay [21]. Our testing demonstrated that 3-OH-cotinine likely contributed to the positives seen in our patient samples. In addition, the spiking studies demonstrated that 3-OH-cotinine does contribute to positive readings by the NicAlert™ test strips. Clinically, it has been observed that 3-OH-cotinine can persist in long-term smokers for an extended period. This scenario can be problematic when assessing smoking abstinence of fewer than two weeks [14]. Positive results from cross-reactivity to 3-OH-cotinine, when cotinine results are <100 ng/mL, will imply that the patient is actively using nicotine products or had a recent exposure within 4 days of testing.

It has been suggested that 6-8 weeks of cessation prior to surgery may reduce postoperative morbidity [22]. Assessment of healing rates on incisions after different time points post-cessation indicated that the largest treatment effects were seen after 4 weeks of smoking abstinence [3].

Given the information above and the findings of this study demonstrating NicAlert™ test positivity due to nicotine metabolites with longer detection windows, it may be valuable to require a 6-week period of tobacco abstinence before surgery if this POC screening test is used. This would diminish the 3-OH-cotinine urine concentrations for compliant patients and improve the performance of NicAlert™ as a screening test. It is also important to convey an additional limitation of this screening test: it does not distinguish between tobacco use, e-cigarette use (vaping), and nicotine replacement therapy.

Conclusion

Nicotine testing is utilized to support several clinical and forensic applications. However, further studies are necessary to clearly define the expected concentrations of individual nicotine metabolites to distinguish between active smoking, passive exposure, and non-smoking. Additional improvements in POC methods to increase specificity would allow for wider utilization of this method. Currently, immunoassays are useful for establishing whether a person has abstained from nicotine use. However, LC-MS/MS offers a more sensitive and specific method for classifying nicotine use. NicAlert™ test strips demonstrated high sensitivity in comparison to LC-MS/MS and EIA results to assess recent tobacco exposure, due to the cross-reactivity with 3-OH-cotinine. This implies that recent nicotine exposure via passive, active, or chronic use, during the 6-week period, would be detected by the NicAlert™ test strip. NicAlert™ test strip specificity may be increased by abstaining from nicotine exposure for more than 6 weeks when levels of 3-OH-cotinine should be undetectable, and the test would result in a more accurate classification of smoking status prior to surgery.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

Funding

None declared.

Acknowledgement

Authors sincerely appreciate the guidance, editing, and review of the manuscript by Dr. Christopher M. Lehman.

Author Contributions Statement

All authors have made substantial contributions to the design and/or acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of the data as well as the drafting and the editing of the final manuscript.

References

2. Britton J. Progress with the global tobacco epidemic. The Lancet. 2015 Mar 14;385(9972):924-6.

3. Mills E, Eyawo O, Lockhart I, Kelly S, Wu P, Ebbert JO. Smoking cessation reduces postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Medicine. 2011 Feb 1;124(2):144-54.

4. Lakshmipathy N, Bokesch PM, Cowan DE, Lisman SR, Schmid CH. Environmental tobacco smoke: a risk factor for pediatric laryngospasm. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 1996 Apr 1;82(4):724-7.

5. Lyons B, Frizelle H, Kirby F, Casey W. The effect of passive smoking on the incidence of airway complications in children undergoing general anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 1996 Apr;51(4):324-6.

6. Drongowski RA, Lee D, Reynolds PI, Malviya S, Harmon CM, Geiger J, et al. Increased respiratory symptoms following surgery in children exposed to environmental tobacco smoke. Pediatric Anesthesia. 2003 May;13(4):304-10.

7. O'Rourke JM, Kalish LA, Mcdaniel S, Lyons B. The effects of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke on pulmonary function in children undergoing anesthesia for minor surgery. Pediatric Anesthesia. 2006 May;16(5):560-7.

8. Skolnick ET, Vomvolakis MA, Buck KA, Mannino SF, Sun LS. Exposure to environmental tobacco smoke and the risk of adverse respiratory events in children receiving general anesthesia. Anesthesiology: The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 1998 May 1;88(5):1144-53.

9. Wong J, Lam DP, Abrishami A, Chan MT, Chung F. Short-term preoperative smoking cessation and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal Canadien D'anesthésie. 2012 Mar 1;59(3):268-79.

10. American Association for Clinical Chemistry. Nicotine and Cotinine, labtestsonline.org: AACC; 2019.

11. Cashman JR, Park SB, Yang ZC, Wrighton SA, Jacob III P, Benowitz NL. Metabolism of nicotine by human liver microsomes: stereoselective formation of trans-nicotine N'-oxide. Chemical Research in Toxicology. 1992 Sep;5(5):639-46.

12. Benowitz NL, Hukkanen J, Jacob P. Nicotine chemistry, metabolism, kinetics and biomarkers. InNicotine psychopharmacology 2009 (pp. 29-60). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

13. Kaivosaari S, Toivonen P, Hesse LM, Koskinen M, Finel M. Nicotine glucuronidation and the human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase UGT2B10. Molecular Pharmacology. 2007 Sep 1;72(3):761-8.

14. Moyer TP, Charlson JR, Enger RJ, Dale LC, Ebbert JO, Schroeder DR, et al. Simultaneous analysis of nicotine, nicotine metabolites, and tobacco alkaloids in serum or urine by tandem mass spectrometry, with clinically relevant metabolic profiles. Clinical Chemistry. 2002 Sep 1;48(9):1460-71.

15. Benowitz NL, Dains KM, Dempsey D, Herrera B, Yu L, Jacob III P. Urine nicotine metabolite concentrations in relation to plasma cotinine during low-level nicotine exposure. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009 Aug 1;11(8):954-60.

16. Cone EJ, Huestis MA. Interpretation of oral fluid tests for drugs of abuse. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2007 Mar;1098:51.

17. Kim S. Overview of cotinine cutoff values for smoking status classification. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2016 Dec;13(12):1236.

18. Heinrich-Ramm R, Wegner R, Garde AH, Baur X. Cotinine excretion (tobacco smoke biomarker) of smokers and non-smokers: comparison of GC/MS and RIA results. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. 2002 Jan 1;205(6):493-9.

19. Suh-Lailam BB, Haglock-Adler CJ, Carlisle HJ, Ohman T, McMillin GA. Reference interval determination for anabasine: a biomarker of active tobacco use. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 2014 Sep 1;38(7):416-20.

20. Tuomi T, Johnsson T, Reijula K. Analysis of nicotine, 3-hydroxycotinine, cotinine, and caffeine in urine of passive smokers by HPLC-tandem mass spectrometry. Clinical Chemistry. 1999 Dec 1;45(12):2164-72.

21. NicAlert. nymox.com; 2020. Available from: https://nymox.com/products#nicalert

22. Møller AM, Villebro N, Pedersen T, Tønnesen H. Effect of preoperative smoking intervention on postoperative complications: a randomised clinical trial. The Lancet. 2002 Jan 12;359(9301):114-7.