Abstract

Globally, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is on the rise with 30-32%, 27-33%, 35-48%, 36%, 9-20%, and 36-38% prevalence in Asia, Europe, North America, South America, Africa, and Australia, respectively. Approximately, 5-10% of NAFLD proceeds to hepatitis called non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NASH often progresses to liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Precise mechanism(s) for the development of HCC is not fully understood in NAFLD and NASH patients. Higher insulin levels in type 2 diabetes (T2D) can result in lipolysis of adipose tissue activating lipid synthesizing enzymes such as fatty acid synthase and stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1, resulting in lipid accumulation in liver. Higher levels of glucose in T2D patients activate carbohydrate response element binding protein and insulin which increases the level of active sterol regulatory element binding protein. These lipogenic transcription factors activate patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein-3 (PNPLA3) from their response elements in the promoter. Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) and persistent organic pollutants (POPs) are implicated in T2D development and NAFLD. The emerging association between POPs, including insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, and diabetes has been noted. However, their connection with NAFLD remains less evident. Here, we reviewed association of POPs, especially EDCs, and role of PNPLA3 in the development of NAFLD and NASH. We also reviewed the role of single nucleotide polymorphisms of PNPLA3’s association with NAFLD.

Keywords

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, Patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing protein 3, Liver fibrosis, Hepatocellular carcinoma

Introduction

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) represents an escalating global health concern. Its prevalence varies significantly across different regions, in Asia it ranges from 30-32%, with notably higher prevalence in the Middle East. Europe reports a prevalence of 27-33%, while North America shows a range of 35-48%. In South America, prevalence is 36-59%, prevalence of 59% is from the meta-analysis of hospital-based studies that included patients with high risk for NAFLD and may not represent prevalence in the general population. Africa has the lowest reported prevalence of 9-20%; however, notable exceptions include Egypt with 57% and Sudan with 28% prevalence. Prevalence of NAFLD in Australia is 36-38% [1,2]. NAFLD is defined by lipid deposition exceeding 5% of liver weight in the absence of excessive alcohol consumption. NAFLD often progresses to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in many patients. NASH is an advanced stage of NAFLD, and it differs from alcohol-mediated steatohepatitis, which resolves with the cessation of alcohol usage. Whereas NASH can progress to fibrosis following hepatocyte death or cirrhosis; it even can lead to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [3,4]. The hallmark of NAFLD is the mark accumulation of triglycerides in the liver, especially in hepatocytes. The sources of fatty acids for excessive liver triglycerides are adipose tissue lipolysis and increased de novo synthesis of lipids in liver [5,6]. Obesity (excessive food intake) and type 2 diabetes (T2D)-induced high blood glucose further worsen lipid levels in the liver [ 7-9].

Obesity, T2D, and high-fat diet lead to fat accumulation in liver causing metabolic stress and predispose hepatocytes to apoptosis [10,11]. The hepatocytes’ death activates hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) which secrete alpha-smooth muscle actin (a-SMA) that causes fibrosis of the liver [12,13]. Among many NAFLD patients, alterations in gut microbiota composition and function (gut dysbiosis) have also been observed. Gut dysbiosis results in increased permeability of intestinal membranes to bacterial-derived lipopolysaccharides which activates immune cells [14,15]. In addition to the activation of immune cells, liver inherent immune, Kupffer cells, are also activated, leading to the progression of NAFLD to NASH [16]. On the other hand, activation of HSCs can trigger the secretion of TGF-b causing fibrosis and cirrhosis [17]. Additional impacts of the cirrhotic liver on HCCs are yet to be fully elucidated [18]. The process of NAFLD leading to NASH is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The conditions and transformation of normal liver to NAFLD, and NASH.

Among NAFLD patients, several gene variants appear to be associated with the disease. The genetic components associated with NAFLD include single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) among the genes involved in the regulation of hepatic lipid turnover. The gene products of patatin-like phospholipase domain-containing 3 (PNPLA3), transmembrane 6 superfamily member 2 (TM6SF2), membrane-bound o-acyltransferase domain-containing 7 (MBOAT7), and glucokinase regulator (GCKR) have been found to associate with NAFLD [19]. Here, we present a comprehensive overview of the genes implicated in hepatic lipid accumulation, with specific focus on the PNPLA3 gene. We explore transcriptional regulation of PNPLA3 in the context of metabolic syndrome and T2D. The review underscores the pivotal role of genetic factors in the progression of NAFLD to NASH. We discussed the impact of an SNP in both the promoter and coding regions of PNPLA3, exploring how these polymorphisms influence the pathogenesis of NAFLD and NASH.

Role of PNPLA3 Gene in Hepatosteatosis

PNPLA3 was cloned in 2001 from mouse 3T3 preadipocytes, which was a feeding-inducible gene and hence named adiponutrin [20]. It is also known as calcium-independent phospholipase A2ε (IPLA2epsilon) and chromosome 22 open reading frame20 (C22 or f20) [20,21]. PNPLA family contains 9 members (PNPLA 1-9), all members of the PNPLA family possess the patatin-like phospholipase domain (PNPLA1-9) [22,23]. Human PNPLA3 contains 9 exons and codes for 481 amino acids. It is localized on chromosome 22 (22q13.31) [23]. Human PNPLA3 gene is bigger (481 AA) than mouse gene (384 AAs) [23]. High expression of the human PNPLA3 gene has been observed in the liver while moderate expression is found in the brain, kidney, skin, and adipose tissues [22,24]. Human PNPLA3 possesses a single nucleotide polymorphism (rs738409) which changes the amino acid, isoleucine to methionine at 148th position (I148M). A strong association was observed between the 148M variant (methionine at 148th position) of PNPLA3 and hepatic fat levels in a genome-wide association studies (GWAS) among Hispanic, African American, and European American individuals [25]. Additionally, multiple studies have found a strong association between liver cirrhosis and PNPLA3 148M variant [26-28]. This variant is also associated with alcoholic liver disease which proceeds from hepatosteatosis to steatohepatitis [29,30]. The variant 148M is implicated in the development of fatty liver in a transgenic mouse model of NAFLD [31]. The role of PNPLA3 is controversial [32-34]. The knockout of the PNPLA3 gene in mice results in neither fatty liver nor abnormal plasma and hepatic triglyceride level [35,36]. However, the knockin of human PNPLA3/148M in mice causes hepatosteatosis after sucrose feeding, and similarly, inflammation after feeding NASH diet [32-34].

The purified PNPLA3 protein, when expressed by baculovirus in Sf9 cells, has shown to possess triacylglycerol lipase and acylglycerol transacylase activities [21]. Huang et al. [37], when used Sf9-cell-expressed purified PNPLA3 protein, observed only lipase activity against triacylglyceride, diacylglyceride, and monoacylglyceride while transacylase activity remained absent. PNPLA3-expressed in lower eukaryotes, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a yeast expression system, produced triglycerides hydrolase and retinyl esterase activity when retinyl-palmitate was used as a substrate [38,39]. Mutant 148M PNPLA3, when expressed in yeast, was substantially reduced, or completely lost the activity of triglyceride hydrolase [38,39]. Once expressed in mammalian cells (e.g., human embryonic kidney HEK293 cells), the purified human PNPLA3 displayed lipase activity [40]. The human PNPLA3 variant (148M), when expressed in Sf9 cells using baculovirus, was shown to lose triglyceride hydrolase activity when triolein was used as substrate [41].

The role of PNPLA3 in lipid metabolism is not well defined. This protein consistently associates with lipid droplets in mammalian cells [41-43]. Notably, both the wild-type PNPLA3 and its variant, 148M, exhibit abnormal, heightened associations with lipid droplets. This interaction disrupts lipid metabolism, leading to elevated lipid levels within mammalian cells. Furthermore, the degradation of the 148M variant, whether through ubiquitination or autophagy-related processes, is diminished. In contrast, the wild-type PNPLA3 undergoes normal turnover during feeding and fasting cycles [32,44,45]. It is presumed that the activity of another homolog, PNPLA2, which is also referred to as adipose triglyceride lipase (ATGL), is inhibited because the activator protein and comparative gene identification 58 (CGI-58), also referred to as abhydrolase domain containing 5 (ABHD5), can no longer competitively associate with PNPLA2, but associates at higher levels with mutant PNPLA3 [43,46,47]. PNPLA3 fails to localize to lipid droplets in CGI-58 liver knock-out cells, thus CGI-58 is needed to direct PNPLA3 association with lipid droplets [43].

There is one rare variant of PNPLA3 (i.e., rs2294918) in which amino acid glutamic acid (E) is changed to lysine (K) at 434 (E434K). The E434K variant attenuates the I148M mediated impact on steatosis and blood enzyme levels of liver injury markers, like aspartate transaminase (AST) and alanine transaminase (ALT) [48,49].

Regulation of the PNPLA3 Gene in T2D and Metabolic Syndrome

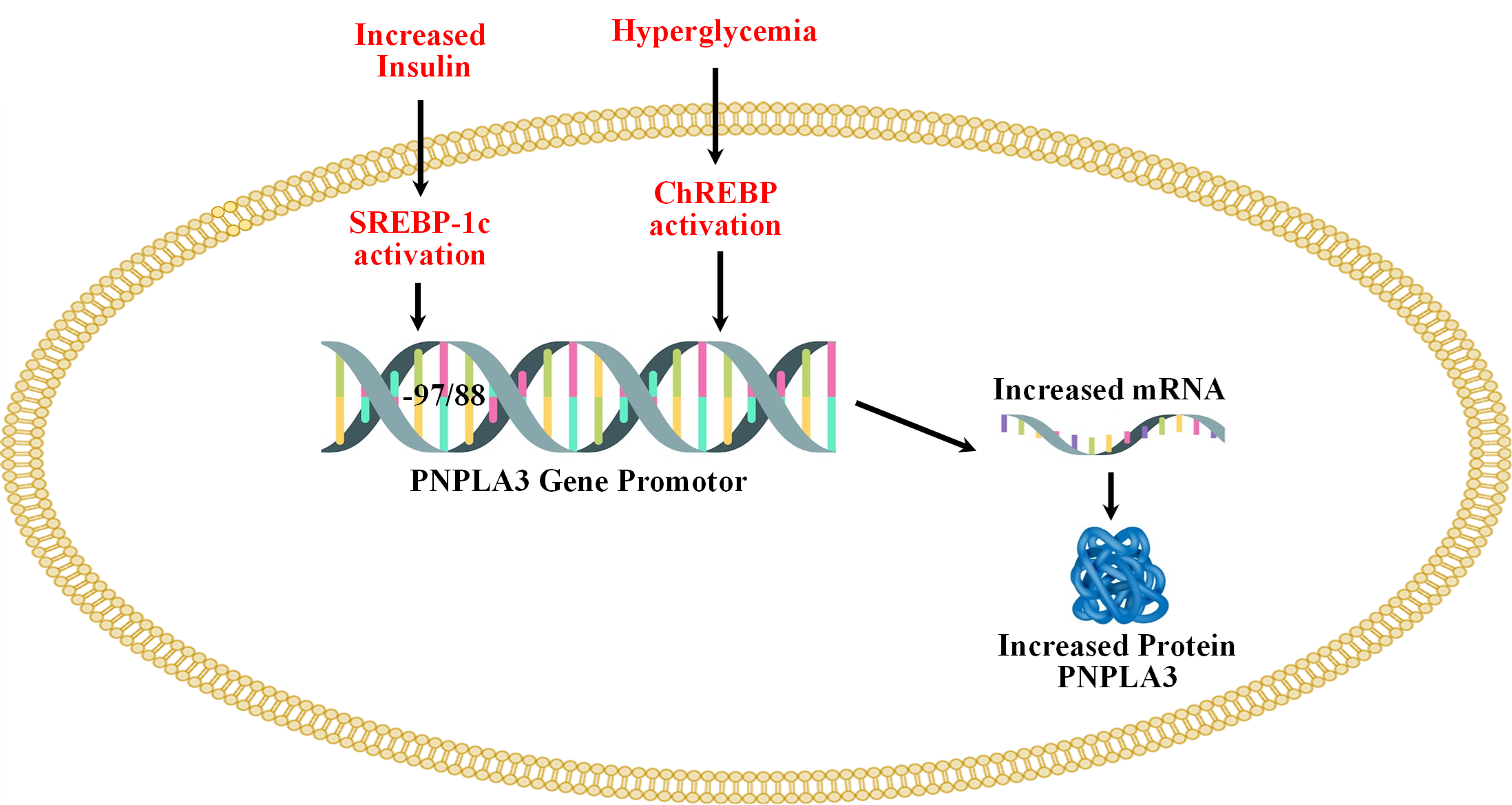

Regulation of the PNPLA3 gene by carbohydrate-response element binding protein (ChREBP) and sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2. Regulation of the PNPLA3 gene by carbohydrate-response element binding protein (ChREBP) and sterol regulatory element binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c).

Both, ChREBP and SREBP-1c regulate PNPLA3 in human hepatocytes and in mouse liver [50-52]. SREBP-1c levels are increased in T2D because of increased levels of circulating insulin [53]. The binding of SREBP-1c to the promoter of PNPLA3 is increased by insulin treatment. Treatment with the inhibitor of PI3K (LY 294002) reduces the insulin-mediated promoter activity of PNPLA3 and SREBP-1c expression in HepG2 cells. The response element of SREBP-1c (SRE) is located at -97/-88 from the start site [51]. SREBP-1c cooperates with the NFY transcription factor to increase the expression of PNPLA3 [51]. Overexpression of SREBP-1c in HepG2 cells increases the expression of PNPLA3 [51]. ChREBP is activated by higher blood glucose levels [54]. ChREBP transcriptional activity is regulated by intermediate products of glycolysis (glucose-6-phosphate (G-6-P) and fructose 2,6-bisphosphate), pentose phosphate pathway (xylulose-5-phosphate), and acetylation which is a posttranscriptional modification mediated by cyclic-AMP-response element binding (CREB) protein p300 [55-60]. ChREBP has two isoforms (i.e., ChREBPa and ChREBPb), and in normal physiological conditions, ChREBPa is localized in the cytosol and upon glucose stimulation, localized to the nucleus and induces transcription of ChREBPb, thus linking both isoforms in the regulation of activity. ChREBPb remains localized in the nucleus that lacks glucose inhibitory domain (LID) which is present in ChREBPa and thus ChREBPb possesses more potent transcriptional activity [61,62]. Under low glucose levels, LID-mediated inhibition of ChREBPa occurs while ChREBPb remains constitutively active [62]. ChREBP is involved in de novo lipogenesis and deletion of ChREBP genes decreases liver triglycerides level via inhibition of de novo lipogenesis [63]. Knockout of ChREBP on ob/ob mice reduced hepatic triglyceride levels [64]. Liver-specific silencing of ChREBP using an adenoviral-based silencing expression system reduced hepatosteatosis in ob/ob mice [65]. PNPLA3 remains under direct control of ChREBP and SREBP-1c in both mouse and human hepatocytes. Infection of adenoviruses expressing ChREBP and SREBP-1c to mouse and human hepatocytes increases the expression of PNPLA3 [50]. Thus, both these transcription factors increase the expression of PNPLA3 [50].

ChREBP is also activated by the liver X receptor (LXR) which heterodimerizes with retinoid X receptors and binds to the LXR response element. Two LXR binding elements are present at 2-4 kb upstream (from +1) of the ChREBPα promoter, thus inducing the expression of the ChREBP gene, where ChREBPa can activate ChREBPb as mentioned above [66]. The site is a response element of the nuclear hormone receptor superfamily which can also bind to thyroid receptors (TR); however, only TRb but not TRa can activate ChREBP in the liver and white adipose tissues [67]. There is also an indirect link of PNPLA3 mutant with the fibrogenesis of the liver. Retinoic acids (all-trans) activate the retinoic acid receptor (RAR) and retinoid X receptor (RXR) transcription factors which downregulate fibrotic genes in HSCs [68-70] The variant PNPLA3 (148M) decreases retinol levels causing downregulation of RAR/RXR target genes in the hepatic stellate cell line [71].

Role of Xenobiotics and Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) in Type 2 Diabetes

To address the growing needs of expanding human population and enhance overall health, it is essential to develop safe industrial, consumer, and agricultural products. Humans have synthesized a range of chemicals and introduced them into the environment to achieve several objectives. These synthetic chemicals, which do not naturally occur, serve diverse functions, including roles as pesticides, fertilizers, plasticizers, antimicrobials, detergents, fire-fighting agents like flame retardants, and others. Moreover, the production of various nanomaterials has been pursued, which may potentially influence genetics and epigenetics [72]. Notably, these chemicals, which can affect human and wildlife health via multiple pathways, have now become ubiquitous in the environment. Such contamination may result in different types of health issues, including cardiovascular disorders, pulmonary diseases, and disruption in the hormonal signaling pathways vital for endocrine functions. Such disruption in the hormonal signaling pathways, which is part of the endocrine system, is referred to as endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) [73]. Table 1 describes the common chemicals which are used by humans and classified as EDCs and are also implicated in NAFLD [74]. The EDC list is ever increasing due to newer chemicals are continuously being introduced.

|

Chemicals |

EDC |

Diabetes |

NAFLD |

|

Hexachlorocyclohexane |

139 |

+ 140 |

+ 141 |

|

Chlordecone |

142 |

|

+ 143 |

|

Polychlorinated Biphenyls (PCBs)/Aroclor, polychlorinated dibenzofuran (PCDFs) |

+ 139, 144, 145 |

+ 139, 146 |

+ 147 |

|

Aldrin, chlordane. Heptachlor, dichlorvos, trichlorfon and cyanazine |

145,148, 149, 150, 151 152 |

+ 153 |

|

|

trans-nonachlor, oxychlordane, β-hexachlorocyclohexane, p,p′-DDT, and p,p′-DDE |

139 |

+ 154, 155 |

156 |

|

Oxychlordane, Chlordanes |

+ 139 |

+ 149 |

+ 133 |

|

Pyrethroid |

157 |

100 |

+ 128 |

|

2,4-dichlorophenoxy acetic acid (2,4-D) 2,4,5-T/2,4,5-TP |

144 |

+ 158 |

|

|

Fonofos, Phorate, parathion |

139 |

+ 158, +159 |

|

|

Pesticides including organochlorines, organophosphates, pyrethrins, and herbicides |

|

153, 160, 161, 162 |

|

|

Cyproconazole, Dazomet, Fluazinam, hexaconazole, Pyrasulfotole metabolite, and Acequinocyil |

|

|

163, 136 |

|

Myclobutanil |

|

|

+164 |

|

Mancozeb |

165 |

|

+166 |

|

Hexaconazole |

167 |

|

+ 168 |

|

Glyphosate |

169 |

+ 170 |

+131, 132, 170 |

|

PFAS |

139 |

|

+171 |

|

PFOA, PFOS |

172 |

|

+173, 174 |

|

+ shows positive impacts. For details, readers are directed to 73, 74, 138, 175, 176. |

|||

The identification of common structural characteristics among various chemicals that lead to ED is a significant challenge. These chemicals seem to induce ED through diverse mechanisms. Nevertheless, certain structural features might offer predictive insights regarding their potential as endocrine disruptors [75,76]. The harmful impacts of EDCs appear to associate with their capacity in terms of possible regulation of the transcription by the nuclear hormone receptor (NR) superfamily members and aryl hydrocarbon receptor [77-79] Different mechanisms of action might be involved by EDCs. For example, some of the xenobiotics, especially EDCs linked to T2D, are discussed below. Effects on T2D for the chemicals, primarily used in the production of various plastics, e.g., bisphenol A (BPA), appear to be controversial. Some studies have shown that BPA exposure might lead to possible insulin resistance, while possible in-utero exposure might result in long-term perinatal adverse effects [80]. Other studies have shown the association of BPA with the development of insulin resistance, loss of glucose homeostasis, and T2D among various populations [81]. The presence of BPA in urine has been reported to associate with the risk of T2D, while some other studies demonstrate no linkage between T2D and BPA exposure [80,82,83]. BPA exposure has shown to decrease the expression of adiponectin from adipocytes, while it seems to increase interleukin 6 (IL-6) and monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP1) levels [84]. Hypoadiponectinemia was also shown to link to insulin resistance and T2D [85-88]. Likewise, urinary phthalates and their metabolites might associate with the initiation and/or progression of diabetes among women and geriatrics [89,90]. Of chlorinated hydrocarbons, chlordane and its derivatives found in pesticides might result in the exposure of humans via direct/indirect contact. Some studies have shown that oxychlordane, heptachlor, and chlordane exposure might associate with T2D [91] Exposure to parabens, which are alkyl esters of p-hydroxybenzoic acid, can simply happen as it has a wide antibacterial preservative application [92]. In a case-control study conducted in Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, parabens were found among individuals with T2D [93]. Further, the exposure of humans to pesticides and persistent organic pollutants (POPs) (e.g., oxychlordane, polychlorinated dibenzodioxins, dibenzofurans, dichlorodiphenyldichloroethylene (DDE), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), hexachlorobenzene (HCB), and hexachlorocyclohexane) appears to increase the risk of T2D [94-97]. Similarly, exposure to chemicals such as insecticides and herbicides (pyrethroids, carbamates, 2,4-D, and 2,4,5-T) is a known risk factor for T2D [98-101]. It should be noted that exposure to chemicals such as BPA during pregnancy might increase the incidence of gestational diabetes [102]. Besides, gestational exposure to EDC might result in some epigenetic alterations, which can potentially predispose humans to different kinds of health risks including T2D [103]. During the first trimester of pregnancy, exposure to some chemicals (e.g., organophosphate (OP), organochlorine (OC), and carbamate (CB)) can markedly enhance the risk of gestational diabetes [104-106]. Additionally, upon poisoning with OP and CB pesticides, glycosuria has been observed transiently in human patients [107]. PCB, TCDD, p’,p’-DDE, are suspected to contribute to T2D [108-112]. Several studies in animals (e.g., rats, fresh-water fish, and European eel) have shown a significant rise in blood glucose levels after exposure to insecticides like carbofuran, dimethoate, and fenitrothion [113-115]. Similarly, exposure of diazinon to rats, and carbaryl and phorate to freshwater fish have resulted in hyperglycemia [116-118]. The acute and subchronic exposure of rats and American kestrels to malathion resulted in hyperglycemia [119-121]. Despite such reports, there are some contradictory observations with other OP (e.g., soman and VX), in which glycemic states were not reported [122]. Remarkably, exposure to azynphos methyl, malathion, and diazinon in mice and rats was shown to alter the after-meal rise in glucose levels [123,124]. Readers are directed to Karami-Mohajeri and Abdollahi for detailed information about pesticides' effects on hyperglycemia [125].

Link of Insecticides Exposure to Liver Steatosis and Inflammation

To date, pesticides have been commonly used to control pests and vector-borne diseases, which seems to be necessary for high agricultural output and mitigating the world food requirement [126,127]. In a recent report, exposure to DDT + permethrin (PMT) at higher doses (DDT-15/PMT-15 vs DDT-150/PMT-150) has been reported to significantly enhance liver steatosis when hepatocytes grown on a chip were analyzed. Metabolite and transcriptomic analyses revealed the effects of DDT and PMT mixture on the development of the hepatosteatosis pathway [128]. Pesticides were implicated in toxicant-associated steatohepatitis (TASH) and NALFD [129]. Pesticides, like chlordecone, atrazine, and paraquat are implicated in steatohepatitis [130]. TCDD and PCB exposure to animals causes lipid accumulation in the liver; nevertheless, human exposure to TCDD and PCBs is not likely linked to hepatosteatosis [130]. Roundup, herbicide glyphosate, which is used in lawn management, exposure results in the fatty liver; exposure to minute quantities of glyphosate to rats has shown to develop fatty liver disease [131,132].

The data analysis of OC pesticides and NAFLD in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (2003-2004) indicated that oxychlordane insecticide is associated with NAFLD [133]. The p’p’-DDT metabolite, p’p’-DDE, and trans-nonachlor were also associated with NAFLD but a statistically significant association was not observed [133]. The relationship between metabolic syndrome in non-diabetic adults and their serum levels of POPs has been noted in the NHANES data from 1999 to 2022. Furthermore, the connection between metabolic syndrome and NAFLD is well-established, particularly in adults with diabetes [134]. In one study, Wahlang observed that the insecticide and metal exposure was associated with NAFLD biomarkers in the NHANES (2003-2004) [135]. The U.S. EPA database with animal studies, known as the Toxicological Reference Database (ToxRefDB), was designed by the National Center for Computational Toxicology and the U.S. EPA Office of Pesticide Programs which includes pesticide registration data of the past 30 years. ToxRefDB found association of 42 toxicants (474 animal studies) with fatty liver disease (TAFLD), same as NAFLD [136]. Most of these compounds were pesticides, which included fungicides, herbicides, insecticides, and miticides [136-138]. The association of past OC insecticides usage, which are still present in the environment, has been established with new cases of fatty liver disease [137]. A summary of the studies for POPs, especially EDCs, to diabetes and NAFLD is presented in Table 1.

Targeting PNPLA3 for the Treatment of NAFLD

Looking at the prevalence of I148M variant in Hispanics and its role in NAFLD, the very first approach is to down-regulate the expression of I148M by microRNA or antisense RNA. A recent study reported that a triantennary N acetylgalactosamine (GalNAC3) conjugated antisense oligonucleotides (ASO) targeting PNPLA3 significantly reduces liver steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis in a 148M knockin mouse model [33]. Reduction in liver lipid is also observed by adeno-associated virus (AAV)-mediated shRNA delivery to 148M knockin mice [44]. Targeting the mutant (I148M) should be preferred as the function of WT-PNPLA3 is not well defined. Targeting PNPLA3 (148M) protein for degradation can be beneficial. Applying proteolysis-targeting chimera (PROTAC)-mediated degradation of Halo-tagged PNPLA3 variant (148M) has exhibited a significant effect on lowering hepatic lipid levels [44]. Another approach should be directed to CGI-58, binding with WT-PNPLA3 but not with PNPLA3 (I148M), which could activate WT-PNPLA3 and offer beneficial effects in lowering the hepatic lipid levels [23]. Therefore, a molecule or a mixture that activates WT-PNPLA3 and possibly degrade PNPLA3 variant 148M is needed before humans face the burgeoning crisis of NAFLD.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved a new medicine, resmetirom (RezdiffraTM, Madrigal Pharmaceuticals, Inc.) on March 14, 2024, for patients who are progressing from NASH to fibrosis [177]. It is a highly selective thyroid hormone receptor-β (TRβ), a nuclear receptor superfamily, agonist. It significantly decreases intra-hepatic lipids by increasing mitochondrial β oxidation and thus improving hepatocyte mitochondrial function in later stage NASH patients [178].

Concluding Remarks

The relationship between POPs (e.g., pesticides and EDCs) and the onset and progression of T2D is not yet fully understood, particularly for its connection to hepatic steatosis. Recent studies by the NHANES suggest a potential link between these chemicals and NAFLD. The growing prevalence of T2D globally underscores the significance of environmental factors, notably the impact of synthetic chemicals on metabolic disorders and their association with hepatosteatosis. Over the past thirty years, there has been a striking increase in the cases of diabetes and coincidingly escalating NAFLD incidences. The global prevalence of NAFLD among adults is estimated to be 32% (40% in males, 26% in females); prevalence has increased from 26% in or before 2005 to 38% in 2016 or later [179]. These trends indicate that while there may be various risk factors for these diseases, the exposure to POPs is increasingly being recognized as one of the critical factors contributing to the surge in diabetes and NAFLD cases.

Looking forward, it is imperative to deepen our understanding of how environmental pollutants like POPs interact with human health, particularly in the context of chronic diseases such as T2D and NAFLD. Such an understanding could lead to more effective strategies for prevention and management of these diseases. There is a growing need for rigorous research to explore the exact impacts of these chemicals on metabolic health holistically. Such studies would not only help in elucidating the mechanisms underlying the association between POPs and metabolic diseases but could also frame public health policies aimed at reducing exposure to these harmful substances. Furthermore, considering the escalating trends in T2D and NAFLD, there is an urgent requirement for public health initiatives that address the combined impact of lifestyle and environmental factors for these conditions. This holistic approach could be vital in mitigating the rising tide of these diseases in the coming decades and pave the way towards development of smart precision medicines for targeted therapy, such as the new FDA approved drug for these diseases. The new drug, resmetirom, is very recently approved by FDA for the treatment of patients who are progressing from NASH to fibrosis but not for the treatment/prevention of NAFLD. Fortunately, several clinical trials are underway (https://clinicaltrials.gov/) and we hope treatments for NAFLD will also become available soon.

Highlights

- Globally, NAFLD is on the rise - prevalence is ~32% (40% in males, 26% in females) which increased from 26% to 38% between ≤ 2005 and ≥ 2016.

- Prevalence is 30-32%, 27-33%, 35-48%, 36%, 9-20%, and 36-38% in Asia, Europe, North America, South America, Africa, and Australia, respectively.

- ~5-10% of NAFLD proceeds to NASH and liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and HCC.

- Higher insulin in T2D can cause lipolysis activating lipid synthesizing enzymes and lipid accumulation by activating carbohydrate response element binding protein and insulin.

- Increase in active sterol regulatory element binding protein activate PNPLA3.

- EDCs and POPs are implicated in T2D development and NAFLD along with single nucleotide polymorphisms of PNPLA3.

Declaration of Interest Statement

We the authors declare that we don’t have any known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Funding

Supported from Health Professions Division (HPD) grant and President’s award (PFRDG) to Rais A Ansari.

References

2. Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2018 Jan;15(1):11-20.

3. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta‐analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016 Jul 1;64(1):73-84.

4. Idalsoaga F, Kulkarni AV, Mousa OY, Arrese M, Arab JP. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and alcohol-related liver disease: two intertwined entities. Frontiers in Medicine. 2020 Aug 20;7:448.

5. Fernando DH, Forbes JM, Angus PW, Herath CB. Development and progression of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the role of advanced glycation end products. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2019 Oct 11;20(20):5037.

6. Pierantonelli I, Svegliati-Baroni G. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: basic pathogenetic mechanisms in the progression from NAFLD to NASH. Transplantation. 2019 Jan 1;103(1):e1-3.

7. Tomah S, Alkhouri N, Hamdy O. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and type 2 diabetes: where do Diabetologists stand?. Clinical Diabetes and Endocrinology. 2020 Dec;6:9.

8. Scapaticci S, D’Adamo E, Mohn A, Chiarelli F, Giannini C. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in obese youth with insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2021 Apr 6;12:639548.

9. Francque SM, Dirinck E. NAFLD prevalence and severity in overweight and obese populations. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2023 Jan 1;8(1):2-3.

10. Eng JM, Estall JL. Diet-induced models of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: food for thought on sugar, fat, and cholesterol. Cells. 2021 Jul 16;10(7):1805.

11. Zhang H, Léveillé M, Courty E, Gunes A, N. Nguyen B, Estall JL. Differences in metabolic and liver pathobiology induced by two dietary mouse models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2020 Nov 1;319(5):E863-76.

12. Alkhouri N, Carter-Kent C, Feldstein AE. Apoptosis in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2011 Apr 1;5(2):201-12.

13. Wang M, Li L, Xu Y, Du J, Ling C. Roles of hepatic stellate cells in NAFLD: From the perspective of inflammation and fibrosis. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 2022 Oct 13;13:958428.

14. Khan A, Ding Z, Ishaq M, Bacha AS, Khan I, Hanif A, et al. Understanding the effects of gut microbiota dysbiosis on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and the possible probiotics role: recent updates. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2021;17(3):818-33.

15. Song Q, Zhang X. The role of gut–liver axis in gut microbiome dysbiosis associated NAFLD and NAFLD-HCC. Biomedicines. 2022 Feb 23;10(3):524.

16. Chen J, Deng X, Liu Y, Tan Q, Huang G, Che Q, et al. Kupffer cells in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: friend or foe?. International Journal of Biological Sciences. 2020;16(13):2367-78.

17. Dewidar B, Meyer C, Dooley S, Meindl-Beinker N. TGF-β in hepatic stellate cell activation and liver fibrogenesis—updated 2019. Cells. 2019 Nov 11;8(11):1419.

18. Anstee QM, Reeves HL, Kotsiliti E, Govaere O, Heikenwalder M. From NASH to HCC: current concepts and future challenges. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2019 Jul;16(7):411-28.

19. Dongiovanni P, Valenti L. Genetics of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2016 Aug 1;65(8):1026-37.

20. Baulande S, Lasnier F, Lucas M, Pairault J. Adiponutrin, a transmembrane protein corresponding to a novel dietary-and obesity-linked mRNA specifically expressed in the adipose lineage. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001 Sep 7;276(36):33336-44.

21. Jenkins CM, Mancuso DJ, Yan W, Sims HF, Gibson B, Gross RW. Identification, cloning, expression, and purification of three novel human calcium-independent phospholipase A2 family members possessing triacylglycerol lipase and acylglycerol transacylase activities. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004 Nov 19;279(47):48968-75.

22. Wilson PA, Gardner SD, Lambie NM, Commans SA, Crowther DJ. Characterization of the human patatin-like phospholipase family. Journal of Lipid Research. 2006 Sep 1;47(9):1940-9.

23. Dong XC. PNPLA3—a potential therapeutic target for personalized treatment of chronic liver disease. Frontiers in Medicine. 2019 Dec 17;6:304.

24. Huang Y, He S, Li JZ, Seo YK, Osborne TF, Cohen JC, et al. A feed-forward loop amplifies nutritional regulation of PNPLA3. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2010 Apr 27;107(17):7892-7.

25. Romeo S, Kozlitina J, Xing C, Pertsemlidis A, Cox D, Pennacchio LA, et al. Genetic variation in PNPLA3 confers susceptibility to nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nature Genetics. 2008 Dec;40(12):1461-5.

26. Shen JH, Li YL, Li D, Wang NN, Jing L, Huang YH. The rs738409 (I148M) variant of the PNPLA3 gene and cirrhosis: a meta-analysis. Journal of Lipid Research. 2015 Jan 1;56(1):167-75.

27. Kupcinskas J, Valantiene I, Varkalaitė G, Steponaitiene R, Skieceviciene J, Sumskiene J, et al. PNPLA3 and RNF7 Gene Variants are Associated with the Risk of Developing Liver Fibrosis and Cirrhosis in an Eastern European Population. Journal of Gastrointestinal & Liver Diseases. 2017 Mar 1;26(1):37-43.

28. Falleti E, Fabris C, Cmet S, Cussigh A, Bitetto D, Fontanini E, et al. PNPLA3 rs738409C/G polymorphism in cirrhosis: relationship with the aetiology of liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence. Liver International. 2011 Sep;31(8):1137-43.

29. Chamorro AJ, Torres JL, Mirón‐Canelo JA, González‐Sarmiento R, Laso FJ, Marcos M. Systematic review with meta‐analysis: the I148M variant of patatin‐like phospholipase domain‐containing 3 gene (PNPLA3) is significantly associated with alcoholic liver cirrhosis. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2014 Sep;40(6):571-81.

30. Burza MA, Molinaro A, Attilia ML, Rotondo C, Attilia F, Ceccanti M, et al. PNPLA3 I148M (rs738409) genetic variant and age at onset of at‐risk alcohol consumption are independent risk factors for alcoholic cirrhosis. Liver International. 2014 Apr;34(4):514-20.

31. Li JZ, Huang Y, Karaman R, Ivanova PT, Brown HA, Roddy T, et al. Chronic overexpression of PNPLA3 I148M in mouse liver causes hepatic steatosis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012 Nov 1;122(11):4130-44.

32. BasuRay S, Smagris E, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. The PNPLA3 variant associated with fatty liver disease (I148M) accumulates on lipid droplets by evading ubiquitylation. Hepatology. 2017 Oct;66(4):1111-24.

33. Lindén D, Ahnmark A, Pingitore P, Ciociola E, Ahlstedt I, Andréasson AC, et al. Pnpla3 silencing with antisense oligonucleotides ameliorates nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and fibrosis in Pnpla3 I148M knock-in mice. Molecular Metabolism. 2019 Apr 1;22:49-61.

34. Smagris E, BasuRay S, Li J, Huang Y, Lai KM, Gromada J, et al. Pnpla3I148M knockin mice accumulate PNPLA3 on lipid droplets and develop hepatic steatosis. Hepatology. 2015 Jan;61(1):108-18.

35. Basantani MK, Sitnick MT, Cai L, Brenner DS, Gardner NP, Li JZ, et al. Pnpla3/Adiponutrin deficiency in mice does not contribute to fatty liver disease or metabolic syndrome [S]. Journal of Lipid Research. 2011 Feb 1;52(2):318-29.

36. Chen W, Chang B, Li L, Chan L. Patatin‐like phospholipase domain‐containing 3/adiponutrin deficiency in mice is not associated with fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2010 Sep;52(3):1134-42.

37. Huang Y, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Expression and characterization of a PNPLA3 protein isoform (I148M) associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011 Oct 28;286(43):37085-93.

38. Pingitore P, Pirazzi C, Mancina RM, Motta BM, Indiveri C, Pujia A, et al. Recombinant PNPLA3 protein shows triglyceride hydrolase activity and its I148M mutation results in loss of function. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 2014 Apr 1;1841(4):574-80.

39. Pirazzi C, Valenti L, Motta BM, Pingitore P, Hedfalk K, Mancina RM, et al. PNPLA3 has retinyl-palmitate lipase activity in human hepatic stellate cells. Human Molecular Genetics. 2014 Aug 1;23(15):4077-85.

40. Lake AC, Sun Y, Li JL, Kim JE, Johnson JW, Li D, et al. Expression, regulation, and triglyceride hydrolase activity of Adiponutrin family members. Journal of Lipid Research. 2005 Nov 1;46(11):2477-87.

41. He S, McPhaul C, Li JZ, Garuti R, Kinch L, Grishin NV, et al. A sequence variation (I148M) in PNPLA3 associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease disrupts triglyceride hydrolysis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010 Feb 26;285(9):6706-15.

42. Murugesan S, Goldberg EB, Dou E, Brown WJ. Identification of diverse lipid droplet targeting motifs in the PNPLA family of triglyceride lipases. PLoS One. 2013 May 31;8(5):e64950.

43. Wang Y, Kory N, BasuRay S, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. PNPLA3, CGI‐58, and inhibition of hepatic triglyceride hydrolysis in mice. Hepatology. 2019 Jun;69(6):2427-41.

44. BasuRay S, Wang Y, Smagris E, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Accumulation of PNPLA3 on lipid droplets is the basis of associated hepatic steatosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2019 May 7;116(19):9521-6.

45. Negoita F, Blomdahl J, Wasserstrom S, Winberg ME, Osmark P, Larsson S, et al. PNPLA3 variant M148 causes resistance to starvation‐mediated lipid droplet autophagy in human hepatocytes. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2019 Jan;120(1):343-56.

46. Chamoun Z, Vacca F, Parton RG, Gruenberg J. PNPLA3/adiponutrin functions in lipid droplet formation. Biology of the Cell. 2013 May;105(5):219-33.

47. Yang A, Mottillo EP, Mladenovic-Lucas L, Zhou L, Granneman JG. Dynamic interactions of ABHD5 with PNPLA3 regulate triacylglycerol metabolism in brown adipocytes. Nature Metabolism. 2019 May;1(5):560-9.

48. Donati B, Motta BM, Pingitore P, Meroni M, Pietrelli A, Alisi A, et al. The rs2294918 E434K variant modulates patatin‐like phospholipase domain‐containing 3 expression and liver damage. Hepatology. 2016 Mar;63(3):787-98.

49. Schwartz BE, Rajagopal V, Smith C, Cohick E, Whissell G, Gamboa M, et al. Discovery and targeting of the signaling controls of PNPLA3 to effectively reduce transcription, expression, and function in pre-clinical NAFLD/NASH settings. Cells. 2020 Oct 7;9(10):2247.

50. Dubuquoy C, Robichon C, Lasnier F, Langlois C, Dugail I, Foufelle F, et al. Distinct regulation of adiponutrin/PNPLA3 gene expression by the transcription factors ChREBP and SREBP1c in mouse and human hepatocytes. Journal of Hepatology. 2011 Jul 1;55(1):145-53.

51. Liang H, Xu J, Xu F, Liu H, Yuan D, Yuan S, et al. The SRE Motif in the Human PNPLA3 Promoter (− 97 to− 88 bp) Mediates Transactivational Effects of SREBP‐1c. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2015 Sep;230(9):2224-32.

52. Perttilä J, Huaman-Samanez C, Caron S, Tanhuanpää K, Staels B, Yki-Järvinen H, et al. PNPLA3 is regulated by glucose in human hepatocytes, and its I148M mutant slows down triglyceride hydrolysis. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2012 May 1;302(9):E1063-9.

53. Ferré P, Phan F, Foufelle F. SREBP-1c transcription factor and lipid homeostasis: clinical perspective. Horm Res. 2007;68(2):72-82.

54. Li MV, Chen W, Poungvarin N, Imamura M, Chan L. Glucose-mediated transactivation of carbohydrate response element-binding protein requires cooperative actions from Mondo conserved regions and essential trans-acting factor 14-3-3. Molecular Endocrinology. 2008 Jul 1;22(7):1658-72.

55. Iizuka K. The transcription factor carbohydrate-response element-binding protein (ChREBP): A possible link between metabolic disease and cancer. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease. 2017 Feb 1;1863(2):474-85.

56. Arden C, Tudhope SJ, Petrie JL, Al-Oanzi ZH, Cullen KS, Lange AJ, et al. Fructose 2, 6-bisphosphate is essential for glucose-regulated gene transcription of glucose-6-phosphatase and other ChREBP target genes in hepatocytes. Biochemical Journal. 2012 Apr 1;443(1):111-23.

57. Dentin R, Tomas-Cobos L, Foufelle F, Leopold J, Girard J, Postic C, et al. Glucose 6-phosphate, rather than xylulose 5-phosphate, is required for the activation of ChREBP in response to glucose in the liver. Journal of Hepatology. 2012 Jan 1;56(1):199-209.

58. Iizuka K, Wu W, Horikawa Y, Takeda J. Role of glucose-6-phosphate and xylulose-5-phosphate in the regulation of glucose-stimulated gene expression in the pancreatic β cell line, INS-1E. Endocrine Journal. 2013;60(4):473-82.

59. Kabashima T, Kawaguchi T, Wadzinski BE, Uyeda K. Xylulose 5-phosphate mediates glucose-induced lipogenesis by xylulose 5-phosphate-activated protein phosphatase in rat liver. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003 Apr 29;100(9):5107-12.

60. Li MV, Chen W, Harmancey RN, Nuotio-Antar AM, Imamura M, Saha P, et al. Glucose-6-phosphate mediates activation of the carbohydrate responsive binding protein (ChREBP). Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2010 May 7;395(3):395-400.

61. Herman MA, Peroni OD, Villoria J, Schön MR, Abumrad NA, Blüher M, et al. A novel ChREBP isoform in adipose tissue regulates systemic glucose metabolism. Nature. 2012 Apr 19;484(7394):333-8.

62. Li MV, Chang B, Imamura M, Poungvarin N, Chan L. Glucose-dependent transcriptional regulation by an evolutionarily conserved glucose-sensing module. Diabetes. 2006 May 1;55(5):1179-89.

63. Iizuka K, Bruick RK, Liang G, Horton JD, Uyeda K. Deficiency of carbohydrate response element-binding protein (ChREBP) reduces lipogenesis as well as glycolysis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004 May 11;101(19):7281-6.

64. Iizuka K, Miller B, Uyeda K. Deficiency of carbohydrate-activated transcription factor ChREBP prevents obesity and improves plasma glucose control in leptin-deficient (ob/ob) mice. American Journal of Physiology-Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2006 Aug;291(2):E358-64.

65. Dentin R, Benhamed F, Hainault I, Fauveau V, Foufelle F, Dyck JR, et al. Liver-specific inhibition of ChREBP improves hepatic steatosis and insulin resistance in ob/ob mice. Diabetes. 2006 Aug 1;55(8):2159-70.

66. Cha JY, Repa JJ. The liver X receptor (LXR) and hepatic lipogenesis: the carbohydrate-response element-binding protein is a target gene of LXR. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007 Jan 5;282(1):743-51.

67. Gauthier K, Billon C, Bissler M, Beylot M, Lobaccaro JM, Vanacker JM, et al. Thyroid hormone receptor β (TRβ) and liver X receptor (LXR) regulate carbohydrate-response element-binding protein (ChREBP) expression in a tissue-selective manner. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2010 Sep 3;285(36):28156-63.

68. Hellemans K, Grinko I, Rombouts K, Schuppan D, Geerts A. All-trans and 9-cis retinoic acid alter rat hepatic stellate cell phenotype differentially. Gut. 1999 Jul 1;45(1):134-42.

69. Hellemans K, Verbuyst P, Quartier E, Schuit F, Rombouts K, Chandraratna RA, et al. Differential modulation of rat hepatic stellate phenotype by natural and synthetic retinoids. Hepatology. 2004 Jan;39(1):97-108.

70. Wang L, Tankersley LR, Tang M, Potter JJ, Mezey E. Regulation of α2 (I) collagen expression in stellate cells by retinoic acid and retinoid X receptors through interactions with their cofactors. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 2004 Aug 1;428(1):92-8.

71. Bruschi FV, Claudel T, Tardelli M, Caligiuri A, Stulnig TM, Marra F, et al. The PNPLA3 I148M variant modulates the fibrogenic phenotype of human hepatic stellate cells. Hepatology. 2017 Jun;65(6):1875-90.

72. Shekh K, Ansari RA, Omidi Y, Shakil SA. Molecular Impacts of Advanced Nanomaterials at Genomic and Epigenomic Levels. In: Sahu SC, ed. Impact of Engineered Nanomaterials in Genomics and Epigenomics. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2023 May 15. pp. 5-39.

73. Kabir ER, Rahman MS, Rahman I. A review on endocrine disruptors and their possible impacts on human health. Environmental Toxicology and Pharmacology. 2015 Jul 1;40(1):241-58.

74. Ansari RA, Alfuraih S, Shekh K, Omidi Y, Javed S, Shakil SA. Endocrine Disruptors: Genetic, Epigenetic, and Related Pathways. In: Sahu SC, ed. Impact of Engineered Nanomaterials in Genomics and Epigenomics. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2023 May 15. pp. 41-82.

75. Hong H, Tong W, Fang H, Shi L, Xie Q, Wu J, et al. Prediction of estrogen receptor binding for 58,000 chemicals using an integrated system of a tree-based model with structural alerts. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002 Jan;110(1):29-36.

76. Nendza M, Wenzel A, Müller M, Lewin G, Simetska N, Stock F, et al. Screening for potential endocrine disruptors in fish: evidence from structural alerts and in vitro and in vivo toxicological assays. Environmental Sciences Europe. 2016 Dec;28:26.

77. Giulivo M, de Alda ML, Capri E, Barceló D. Human exposure to endocrine disrupting compounds: Their role in reproductive systems, metabolic syndrome and breast cancer. A review. Environmental Research. 2016 Nov 1;151:251-64.

78. Delfosse V, Maire AL, Balaguer P, Bourguet W. A structural perspective on nuclear receptors as targets of environmental compounds. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2015 Jan;36(1):88-101.

79. Nebert DW. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR):“pioneer member” of the basic-helix/loop/helix per-Arnt-sim (bHLH/PAS) family of “sensors” of foreign and endogenous signals. Progress in Lipid Research. 2017 Jul 1;67:38-57.

80. Farrugia F, Aquilina A, Vassallo J, Pace NP. Bisphenol A and type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review of epidemiologic, functional, and early life factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021 Jan;18(2):716.

81. Sabanayagam C, Teppala S, Shankar A. Relationship between urinary bisphenol A levels and prediabetes among subjects free of diabetes. Acta Diabetologica. 2013 Aug;50:625-31.

82. Ahmadkhaniha R, Mansouri M, Yunesian M, Omidfar K, Jeddi MZ, Larijani B, et al. Association of urinary bisphenol a concentration with type-2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering. 2014 Dec;12(1):64.

83. Delepierre J, Fosse-Edorh S, Fillol C, Piffaretti C. Relation of urinary bisphenol concentration and diabetes or prediabetes in French adults: A cross-sectional study. PloS one. 2023 Mar 30;18(3):e0283444.

84. Cimmino I, D’Esposito V, Liguoro D, Liguoro P, Ambrosio MR, Cabaro S, et al. Low-dose Bisphenol-A regulates inflammatory cytokines through GPR30 in mammary adipose cells. Journal of Molecular Endocrinology. 2019 Nov 1;63(4):273-83.

85. Okamoto Y, Kihara S, Ouchi N, Nishida M, Arita Y, Kumada M, et al. Adiponectin reduces atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2002 Nov 26;106(22):2767-70.

86. Matsuda M, Shimomura I, Sata M, Arita Y, Nishida M, Maeda N, et al. Role of adiponectin in preventing vascular stenosis: the missing link of adipo-vascular axis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002 Oct 4;277(40):37487-91.

87. Yamauchi T, Kamon J, Waki H, Terauchi Y, Kubota N, Hara K, et al. The fat-derived hormone adiponectin reverses insulin resistance associated with both lipoatrophy and obesity. Nature Medicine. 2001 Aug;7(8):941-6.

88. Kaser S, Tatarczyk T, Stadlmayr A, Ciardi C, Ress C, Tschoner A, et al. Effect of obesity and insulin sensitivity on adiponectin isoform distribution. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008 Nov;38(11):827-34.

89. James-Todd T, Stahlhut R, Meeker JD, Powell SG, Hauser R, Huang T, et al. Urinary phthalate metabolite concentrations and diabetes among women in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2001–2008. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012 Sep;120(9):1307-13.

90. Lind PM, Zethelius B, Lind L. Circulating levels of phthalate metabolites are associated with prevalent diabetes in the elderly. Diabetes Care. 2012 Jul 1;35(7):1519-24.

91. Lin JY, Yin RX. Exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals and type 2 diabetes mellitus in later life. Exposure and Health. 2023 Mar;15(1):199-229.

92. Liao C, Chen L, Kannan K. Occurrence of parabens in foodstuffs from China and its implications for human dietary exposure. Environment International. 2013 Jul 1;57:68-74.

93. Li AJ, Xue J, Lin S, Al-Malki AL, Al-Ghamdi MA, Kumosani TA, et al. Urinary concentrations of environmental phenols and their association with type 2 diabetes in a population in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Environmental Research. 2018 Oct 1;166:544-52.

94. Jaacks LM, Staimez LR. Association of persistent organic pollutants and non-persistent pesticides with diabetes and diabetes-related health outcomes in Asia: A systematic review. Environment International. 2015 Mar 1;76:57-70.

95. Czajka M, Matysiak-Kucharek M, Jodłowska-Jędrych B, Sawicki K, Fal B, Drop B, et al. Organophosphorus pesticides can influence the development of obesity and type 2 diabetes with concomitant metabolic changes. Environmental Research. 2019 Nov 1;178:108685.

96. Lee DH, Lind PM, Jacobs Jr DR, Salihovic S, Van Bavel B, Lind L. Polychlorinated biphenyls and organochlorine pesticides in plasma predict development of type 2 diabetes in the elderly: the prospective investigation of the vasculature in Uppsala Seniors (PIVUS) study. Diabetes Care. 2011 Aug 1;34(8):1778-84.

97. Lind PM, Lind L. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals and risk of diabetes: an evidence-based review. Diabetologia. 2018 Jul;61:1495-502.

98. Remillard RB, Bunce NJ. Linking dioxins to diabetes: epidemiology and biologic plausibility. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2002 Sep;110(9):853-8.

99. Jia C, Zhang S, Cheng X, An J, Zhang X, Li P, et al. Association between serum pyrethroid insecticide levels and incident type 2 diabetes risk: a nested case–control study in Dongfeng–Tongji cohort. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2022 Sep;37(9):959-70.

100. Park J, Park SK, Choi YH. Environmental pyrethroid exposure and diabetes in US adults. Environmental Research. 2019 May 1;172:399-407.

101. Pesticides B. Study Links Carbamate Insecticides to Diabetes and other metabolic Diseases. https://beyondpesticides.org/dailynewsblog/2017/01/study-links-carbamate-insecticides-diabetes-metabolic-diseases/

102. Zhang W, Xia W, Liu W, Li X, Hu J, Zhang B, et al. Exposure to bisphenol a substitutes and gestational diabetes mellitus: a prospective cohort study in China. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2019 Apr 30;10:262.

103. Alavian‐Ghavanini A, Rüegg J. Understanding epigenetic effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals: from mechanisms to novel test methods. Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 2018 Jan;122(1):38-45.

104. Saldana TM, Basso O, Hoppin JA, Baird DD, Knott C, Blair A, et al. Pesticide exposure and self-reported gestational diabetes mellitus in the Agricultural Health Study. Diabetes Care. 2007 Mar 1;30(3):529-34.

105. Longnecker MP, Klebanoff MA, Brock JW, Zhou H. Polychlorinated biphenyl serum levels in pregnant subjects with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001 Jun 1;24(6):1099-101.

106. Chen JW, Wang SL, Liao PC, Chen HY, Ko YC, Lee CC. Relationship between insulin sensitivity and exposure to dioxins and polychlorinated biphenyls in pregnant women. Environmental Research. 2008 Jun 1;107(2):245-53.

107. Shobha TR, Prakash O. Glycosuria in organophosphate and carbamate poisoning. The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 2000 Dec 1;48(12):1197-9.

108. Rylander L, Rignell-Hydbom A, Hagmar L. A cross-sectional study of the association between persistent organochlorine pollutants and diabetes. Environmental Health. 2005 Dec;4:28.

109. Michalek J, Ketchum N, Tripathi R. Diabetes mellitus and 2, 3, 7, 8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin elimination in veterans of Operation Ranch Hand. Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health Part A. 2003 Jan 1;66(3):211-21.

110. Vasiliu O, Cameron L, Gardiner J, DeGuire P, Karmaus W. Polybrominated biphenyls, polychlorinated biphenyls, body weight, and incidence of adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Epidemiology. 2006 Jul 1;17(4):352-9.

111. Everett CJ, Frithsen IL, Diaz VA, Koopman RJ, Simpson Jr WM, Mainous III AG. Association of a polychlorinated dibenzo-p-dioxin, a polychlorinated biphenyl, and DDT with diabetes in the 1999–2002 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Environmental Research. 2007 Mar 1;103(3):413-8.

112. Rignell-Hydbom A, Rylander L, Hagmar L. Exposure to persistent organochlorine pollutants and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Human & Experimental Toxicology. 2007 May;26(5):447-52.

113. Kamath V, Rajini PS. Altered glucose homeostasis and oxidative impairment in pancreas of rats subjected to dimethoate intoxication. Toxicology. 2007 Mar 7;231(2-3):137-46.

114. Koundinya PR, Ramamurthi R. Effect of organophosphate pesticide Sumithion (Fenitrothion) on some aspects of carbohydrate metabolism in a freshwater fish, Sarotherodon (Tilapia) mossambicus (Peters). Experientia. 1979 Dec;35(12):1632-3.

115. Sancho E, Ferrando MD, Andreu E. Sublethal effects of an organophosphate insecticide on the European eel, Anguilla anguilla. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 1997 Feb 1;36(1):57-65.

116. Jyothi B, Narayan G. Certain pesticide-induced carbohydrate metabolic disorders in the serum of freshwater fish Clarias batrachus (Linn.). Food and Chemical Toxicology. 1999 Apr 1;37(4):417-21.

117. Ueyama J, Kamijima M, Asai K, Mochizuki A, Wang D, Kondo T, et al. Effect of the organophosphorus pesticide diazinon on glucose tolerance in type 2 diabetic rats. Toxicology Letters. 2008 Nov 10;182(1-3):42-7.

118. Pourkhalili N, Pournourmohammadi S, Rahimi F, Vosough-Ghanbari S, Baeeri M, Ostad SN, et al. Usporedba djelovanja blokatora kalcijevih kanala, blokatora autonomnoga živčanog sustava te inhibitora slobodnih radikala na hiposekreciju inzulin iz izolirnih langerhansovih otočića štakora uzrokovanu diazinonom. Arhiv Za Higijenu Rada I Toksikologiju. 2009 Jun 12;60(2):157-64.

119. Ramu A, Slonim AE, London M, Eyal F. Hyperglycemia in acute malathion poisoning. Israel journal of Medical Sciences. 1973 May;9(5):631-4.

120. Rezg R, Mornagui B, Kamoun A, El-Fazaa S, Gharbi N. Effect of subchronic exposure to malathion on metabolic parameters in the rat. Comptes Rendus. Biologies. 2007;330(2):143-7.

121. Rattner BA, Franson JC. Methyl parathion and fenvalerate toxicity in American kestrels: Acute physiological responses and effects of cold. Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 1984 Jul 1;62(7):787-92.

122. Chilcott RP, Dalton CH, Hill I, Davidson CM, Blohm KL, Hamilton MG. Clinical manifestations of VX poisoning following percutaneous exposure in the domestic white pig. Human & Experimental Toxicology. 2003 May;22(5):255-61.

123. Sadeghi-Hashjin G, Moslemi M, Javadi S. The effect of organophosphate pesticides on the blood glucose levels in the mouse. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences: PJBS. 2008 May 1;11(9):1290-2.

124. Alahyary P, Poor MI, Azarbaijani FF, Nejati V. The potential toxicity of diazinon on physiological factors in male rat. Pakistan Journal of Biological Sciences: PJBS. 2008 Jan 1;11(1):127-30.

125. Karami-Mohajeri S, Abdollahi M. Toxic influence of organophosphate, carbamate, and organochlorine pesticides on cellular metabolism of lipids, proteins, and carbohydrates: a systematic review. Human & Experimental Toxicology. 2011 Sep;30(9):1119-40.

126. Ghisari M, Long M, Tabbo A, Bonefeld-Jørgensen EC. Effects of currently used pesticides and their mixtures on the function of thyroid hormone and aryl hydrocarbon receptor in cell culture. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2015 May 1;284(3):292-303.

127. van Den Berg H, Velayudhan R, Yadav RS. Management of insecticides for use in disease vector control: Lessons from six countries in Asia and the Middle East. PLoS neglected tropical diseases. 2021 Apr 30;15(4):e0009358.

128. Jellali R, Jacques S, Essaouiba A, Gilard F, Letourneur F, Gakière B, Legallais C, Leclerc E. Investigation of steatosis profiles induced by pesticides using liver organ-on-chip model and omics analysis. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2021 Jun 1;152:112155.

129. Al-Eryani L. The role of pesticides in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). University of Louisville 2014. https://ir.library.louisville.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1026&context=etd

130. Wahlang B, Beier JI, Clair HB, Bellis-Jones HJ, Falkner KC, McClain CJ, Cave MC. Toxicant-associated steatohepatitis. Toxicologic Pathology. 2013 Feb;41(2):343-60.

131. Poulter S. Britain's most used pesticide is linked to a serious liver disease which can be fatal, shocking new study claims. Daily Mail. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-4102990/Britain-s-used-pesticide-linked-deadly-liver-disease-shocking-new-study-claims.html

132. LiverDoctor. Pesticide Linked To Fatty Liver. https://www.liverdoctor.com/pesticide-linked-to-fatty-liver/

133. Sang H, Lee KN, Jung CH, Han K, Koh EH. Association between organochlorine pesticides and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004. Scientific Reports. 2022 Jul 8;12(1):11590.

134. Lee DH, Lee IK, Jin SH, Steffes M, Jacobs Jr DR. Association between serum concentrations of persistent organic pollutants and insulin resistance among nondiabetic adults: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2002. Diabetes care. 2007 Mar 1;30(3):622-8.

135. Wahlang B, Appana S, Falkner KC, McClain CJ, Brock G, Cave MC. Insecticide and metal exposures are associated with a surrogate biomarker for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2003–2004. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2020 Feb;27(6):6476-87.

136. Al-Eryani L, Wahlang B, Falkner KC, Guardiola JJ, Clair HB, Prough RA, Cave M. Identification of environmental chemicals associated with the development of toxicant-associated fatty liver disease in rodents. Toxicologic pathology. 2015 Jun;43(4):482-97.

137. Pesticides B. Pesticide Exposure Driving Liver Disease through Hormone Disrupting Mechanism. 2022. Beyond Pesticides. https://beyondpesticides.org/dailynewsblog/2022/07/pesticide-exposure-driving-liver-disease-through-hormone-disrupting-mechanisms/#:~:text=(Beyond%20Pesticides%2C%20July%2021%2C,like%20organochlorine%20pesticides%20(OCPs).

138. La Merrill MA, Vandenberg LN, Smith MT, Goodson W, Browne P, Patisaul HB, Guyton KZ, Kortenkamp A, Cogliano VJ, Woodruff TJ, Rieswijk L. Consensus on the key characteristics of endocrine-disrupting chemicals as a basis for hazard identification. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2020 Jan;16(1):45-57.

139. Kumar M, Sarma DK, Shubham S, Kumawat M, Verma V, Prakash A, Tiwari R. Environmental endocrine-disrupting chemical exposure: role in non-communicable diseases. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020 Sep 24;8:553850.

140. Al-Othman A, Yakout S, Abd-Alrahman SH, Al-Daghri NM. Strong associations between the pesticide hexachlorocyclohexane and type 2 diabetes in Saudi adults. International journal of Environmental research and Public Health. 2014 Sep;11(9):8984-95.

141. Rantakokko P, Männistö V, Airaksinen R, Koponen J, Viluksela M, Kiviranta H, Pihlajamäki J. Persistent organic pollutants and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in morbidly obese patients: a cohort study. Environmental Health. 2015 Dec;14:79.

142. Ayhan G, Rouget F, Giton F, Costet N, Michineau L, Monfort C, Thomé JP, Kadhel P, Cordier S, Oliva A, Multigner L. In utero chlordecone exposure and thyroid, metabolic, and sex-steroid hormones at the age of seven years: a study from the TIMOUN mother-child cohort in guadeloupe. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2021 Nov 22;12:771641.

143. TAYLOR JR, SELHORST JB, HOUFF SA, Martinez AJ. Chlordecone intoxication in man: 1. Clinical observations. Neurology. 1978 Jul;28(7):626-30.

144. Mnif W, Hassine AI, Bouaziz A, Bartegi A, Thomas O, Roig B. Effect of endocrine disruptor pesticides: a review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2011 Jun;8(6):2265-303.

145. Encarnação T, Pais AA, Campos MG, Burrows HD. Endocrine disrupting chemicals: Impact on human health, wildlife and the environment. Science Progress. 2019 Mar;102(1):3-42.

146. Silverstone AE, Rosenbaum PF, Weinstock RS, Bartell SM, Foushee HR, Shelton C, et al. Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB) exposure and diabetes: results from the Anniston Community Health Survey. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012 May;120(5):727-32.

147. Armstrong LE, Guo GL. Understanding environmental contaminants’ direct effects on non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progression. Current Environmental Health Reports. 2019 Sep 15;6:95-104.

148. Wrobel MH, Grzeszczyk M, Mlynarczuk J, Kotwica J. The adverse effects of aldrin and dieldrin on both myometrial contractions and the secretory functions of bovine ovaries and uterus in vitro. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2015 May 15;285(1):23-31.

149. Mendes V, Ribeiro C, Delgado I, Peleteiro B, Aggerbeck M, Distel E, et al. The association between environmental exposures to chlordanes, adiposity and diabetes-related features: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Scientific Reports. 2021 Jul 15;11(1):14546.

150. Quintino-Ottonicar GG, Silva LR, Maria VL, Pizzo EM, Santana AC, Lenharo NR, et al. Exposure to Dichlorvos pesticide alters the morphology of and lipid metabolism in the ventral prostate of rats. Frontiers in Toxicology. 2023 Jul 4;5:1207612.

151. Chen H, Dong Y, Li H, Chen Z, Su M, Zhu Q, et al. Trichlorfon blocks androgen synthesis and metabolism in rat immature Leydig cells. Reprod Toxicol. Sep 2023;120:108436.

152. Wirbisky SE, Freeman JL. Atrazine exposure and reproductive dysfunction through the hypothalamus-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis. Toxics. 2015 Nov 2;3(4):414-50.

153. Montgomery MP, Kamel F, Saldana TM, Alavanja MC, Sandler DP. Incident diabetes and pesticide exposure among licensed pesticide applicators: Agricultural Health Study, 1993–2003. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2008 May 15;167(10):1235-46.

154. Codru N, Schymura MJ, Negoita S, Rej R, Carpenter DO, Akwesasne Task Force on the Environment. Diabetes in relation to serum levels of polychlorinated biphenyls and chlorinated pesticides in adult Native Americans. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007 Oct;115(10):1442-7.

155. Cox S, Niskar AS, Narayan KV, Marcus M. Prevalence of self-reported diabetes and exposure to organochlorine pesticides among Mexican Americans: Hispanic health and nutrition examination survey, 1982–1984. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2007 Dec;115(12):1747-52.

156. Howell III GE, McDevitt E, Henein L, Mulligan C, Young D. Trans-nonachlor increases extracellular free fatty acid accumulation and de novo lipogenesis to produce hepatic steatosis in McArdle-RH7777 cells. Toxicology in Vitro. 2018 Aug 1;50:285-92.

157. Brander SM, Gabler MK, Fowler NL, Connon RE, Schlenk D. Pyrethroid pesticides as endocrine disruptors: molecular mechanisms in vertebrates with a focus on fishes. Environmental Science & Technology. 2016 Sep 6;50(17):8977-92.

158. Starling AP, Umbach DM, Kamel F, Long S, Sandler DP, Hoppin JA. Pesticide use and incident diabetes among wives of farmers in the Agricultural Health Study. Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 2014 Sep 1;71(9):629-35.

159. Wei Y, Wang L, Liu J. The diabetogenic effects of pesticides: Evidence based on epidemiological and toxicological studies. Environmental Pollution. 2023 May 31:121927.

160. Evangelou E, Ntritsos G, Chondrogiorgi M, Kavvoura FK, Hernández AF, Ntzani EE, et al. Exposure to pesticides and diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Environment International. 2016 May 1;91:60-8.

161. Juntarawijit C, Juntarawijit Y. Association between diabetes and pesticides: a case-control study among Thai farmers. Environmental Health and Preventive Medicine. 2018 Dec;23(1):3.

162. Pesticide-Induced Diseases: Diabetes. https://www.beyondpesticides.org/resources/pesticide-induced-diseases-database/diabetes

163. ToxRefDB - Release user-friendly web-based tool for mining ToxRefDB (2010).

164. Stellavato A, Lamberti M, Pirozzi AV, de Novellis F, Schiraldi C. Myclobutanil worsens nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: An in vitro study of toxicity and apoptosis on HepG2 cells. Toxicology Letters. 2016 Nov 16;262:100-4.

165. Skalny A, Aschner M, Paoliello M, Santamaria A, Nikitina N, Rejniuk V, et al. Endocrine-disrupting activity of mancozeb. Arhiv Za Farmaciju. 2021;71(6):491-507.

166. Pirozzi AV, Stellavato A, La Gatta A, Lamberti M, Schiraldi C. Mancozeb, a fungicide routinely used in agriculture, worsens nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the human HepG2 cell model. Toxicology Letters. 2016 May 13;249:1-4.

167. Alquraini A. Potency of hexaconazole to disrupt endocrine function with sex hormone-binding globulin. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023 Feb 15;24(4):3882.

168. Imported Bananas. HED Risk Assessment. (1999).

169. de Araújo-Ramos AT, Passoni MT, Romano MA, Romano RM, Martino-Andrade AJ. Controversies on endocrine and reproductive effects of glyphosate and glyphosate-based herbicides: a mini-review. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2021 Mar 15;12:627210.

170. Raphael K. Kids’ glyphosate exposure linked to liver disease and metabolic syndrome. https://www.ehn.org/glyphosate-childrens-health-2659484037.html

171. Das KP, Wood CR, Lin MT, Starkov AA, Lau C, Wallace KB, et al. Perfluoroalkyl acids-induced liver steatosis: Effects on genes controlling lipid homeostasis. Toxicology. 2017 Mar 1;378:37-52.

172. Chaparro-Ortega A, Betancourt M, Rosas P, Vázquez-Cuevas FG, Chavira R, Bonilla E, et al. Endocrine disruptor effect of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) on porcine ovarian cell steroidogenesis. Toxicology in Vitro. 2018 Feb 1;46:86-93.

173. Yan S, Wang J, Dai J. Activation of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins in mice exposed to perfluorooctanoic acid for 28 days. Archives of Toxicology. 2015 Sep;89:1569-78.

174. Wu X, Liang M, Yang Z, Su M, Yang B. Effect of acute exposure to PFOA on mouse liver cells in vivo and in vitro. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2017 Nov;24:24201-6.

175. Dodson RE, Nishioka M, Standley LJ, Perovich LJ, Brody JG, Rudel RA. Endocrine disruptors and asthma-associated chemicals in consumer products. Environmental Health Perspectives. 2012 Jul;120(7):935-43.

176. Gore AC, Crews D, Doan LL, La Merrill M, Patisaul H, Zota A. Introduction to endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs). A Guide for Public Interest Organizations and Policy-Makers. 2014. https://www.endocrine.org/-/media/endosociety/files/advocacy-and-outreach/important-documents/introduction-to-endocrine-disrupting-chemicals.pdf

177. US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first treatment for patients with liver scarring due to fatty liver disease. FDA. 2024. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-treatment-patients-liver-scarring-due-fatty-liver-disease

178. Sinha RA, Yen PM. Thyroid hormone-mediated autophagy and mitochondrial turnover in NAFLD. Cell & Bioscience. 2016 Dec;6:46.

179. Riazi K, Azhari H, Charette JH, Underwood FE, King JA, Afshar EE, et al. The prevalence and incidence of NAFLD worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2022 Sep 1;7(9):851-61.