Abstract

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an increasing health problem when left untreated. NAFLD is defined as accumulation of fat in 5% of the hepatocytes. NAFLD can convert into non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) which is defined as inflammatory NAFLD. Both NAFLD and NASH are observed in individuals suffering from metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes (T2D). Agents which increase the insulin sensitivity for T2D treatment are thiazolidinediones (TZDs) which target nuclear peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ). Therefore, TZD has been investigated as a potential agent for the treatment of NAFLD and NASH. Other members of nuclear receptor families such as constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), farnesoid X receptor (FXR), pregnane and xenobiotic receptor (PXR) and liver X receptor regulate metabolic responses across multiple organ system during eating and fasting. These nuclear receptors are regulators of the axis of gut, liver, and adipose tissue. Abnormal NRs signaling is associated with NAFLD, especially in obesity, increased intestinal permeability of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) followed by inflammation, abnormal hepatic lipid metabolism, and insulin insensitivity. We review nuclear receptor superfamily, its architectural structure, signaling and possible signaling interference in the development of NAFLD. Due to the lack of treatment for NAFLD or NASH, patients' only option is changes in their lifestyle which include weight reduction and less fat intake. This review also examined the possibility of NR mediated treatment of NAFLD. Current clinical trials are focused on separate treatments of different NAFLD states, such as steatosis, inflammation, insulin insensitivity, obesity, and dyslipidemia. Nuclear receptor mediated transcription does not occur in isolation rather many works in coordination, i.e., one NR activation affects other NRs, a process referred to as NR crosstalk resulting in transrepression/transactivation. For the treatment of NAFLD, a tissue specific ligand devoid of NR-crosstalk is likely needed.

Introduction

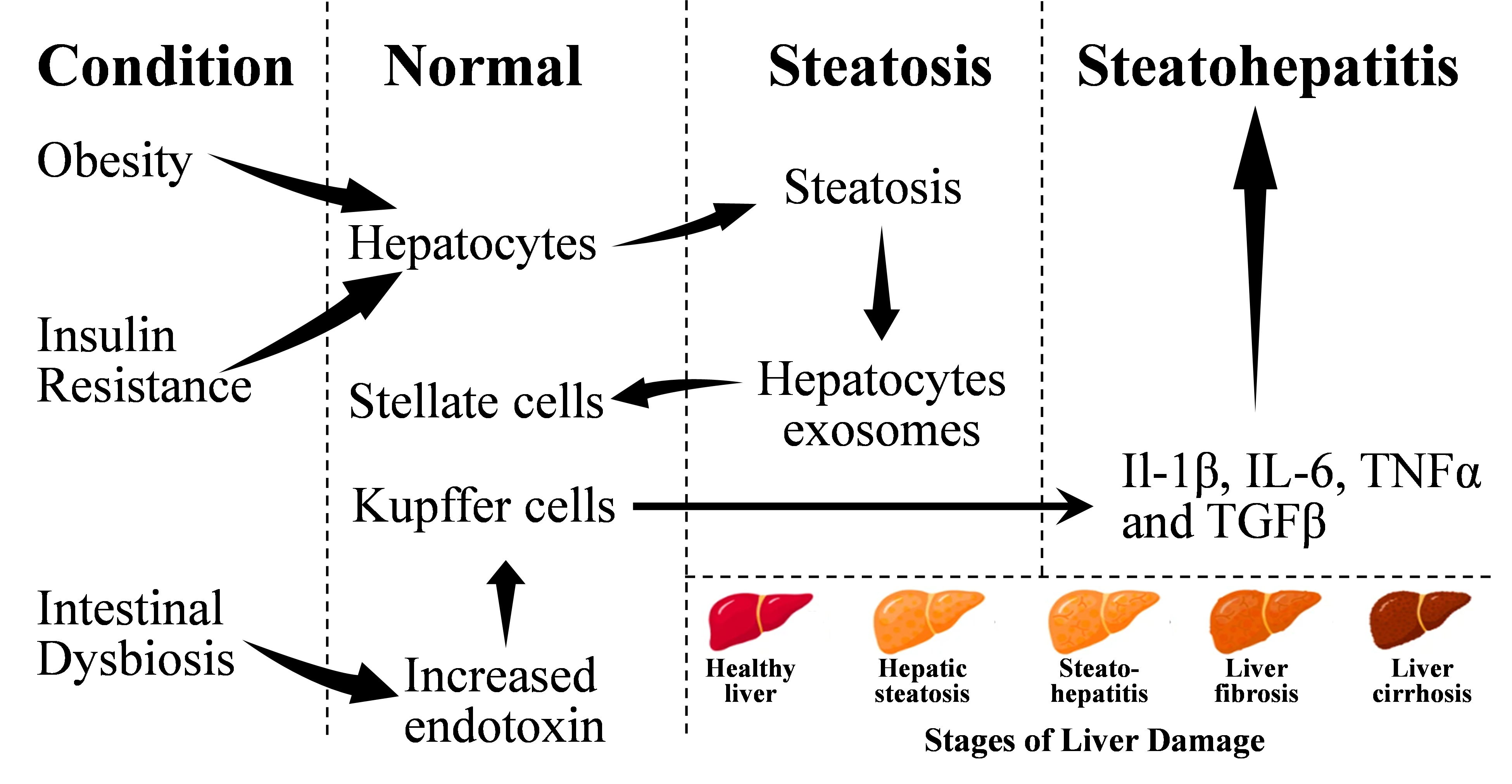

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) with a global occurrence of ~25% is the leading cause of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver steatosis may or may not proceed to inflammation (non-alcoholic hepatitis), however, if steatosis coupled with inflammation, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) will lead to liver fibrosis faster than the NAFLD alone without inflammation. NAFLD is often associated with metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes (T2D) [1]. Metabolic syndrome is defined by a host of interrelated clinical symptoms which include insulin resistance, fasting hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, visceral obesity, and hypertension [2,3]. Nonalcoholic steatosis causes fat infiltration into liver, especially in hepatocytes causing inflammation due to macrophage activation and is defined as NASH without significant alcohol usage [2]. Hepatic stellate cells are activated by the exosomes which are secreted by hepatocytes with lipotoxicity [4]. Dysbiosis is an alteration in gut microbiome that increases intestinal permeability and hence increase transfer of bacterial endotoxins via portal vein into liver [5]. High fat diet (HFD), obesity and NAFLD have been related to the presence of intestinal dysbiosis [5]. Endotoxins in liver, activate Kupffer cells (KCs) and promote release of proinflammatory cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα), interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-6 [6]. Transforming growth factor-β, which is a profibrotic mediator, activates hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) which contribute to fibrotic transformation of liver after hepatocyte death [6]. Hepatic steatosis and steatohepatitis are also caused by chronic alcohol usage which is similar to non-alcoholic hepatosteatosis and steatohepatitis [7]. Both alcoholic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis can lead to significant hepatocyte death which is replaced by the tissues after activation of quiescent HSC in liver [8]. HSCs secrete fibrin causing liver fibrosis which after scarring of liver tissue becomes liver cirrhosis which is a fatal disease. Hepatosteatosis and steatohepatitis are reversible but if not reversed lead to liver fibrosis and cirrhosis. Progression from steatohepatitis to fibrosis can also lead to hepatocellular carcinoma [9].

NAFLD is a chronic disease with an occurrence of 20-40% among general population in industrialized nations. Among these, a portion of 10-20% progress to NASH. NAFLD and NASH are common occurrences among individuals with metabolic syndrome. NASH is closely associated with obesity and T2D, a major global health issue among individuals suffering from obesity and insulin independent diabetes [10]. The incidence of NAFLD could be as high as 90% among individuals with morbid obesity and up to 70% among diabetic patients [11,12].

Several cellular interactions among liver cells, such as hepatocytes, HSCs, and KCs occur during the development of NAFLD [13,14]. NAFLD is driven by overnutrition which causes expansion of adipose depots and ectopic fact accumulation. Macrophage accumulation in these adipose tissues, especially in visceral adipose tissues, creates proinflammatory transition [15]. This creates insulin resistance. With increased insulin, increased lipolysis occurs, which sends unabated fatty acids to liver where increased lipid synthesis occurs de-novo. The imbalance in the utilization of lipids by liver produces lipotoxic lipids, thereby producing cellular stress and endoplasmic stress [2]. This leads to the activation of inflammasome (NLRP3), resulting into hepatocyte death, subsequent inflammation, regeneration of tissue, resulting in fibrogenesis [16,17]. Transition of NAFLD to NASH requires multiple contributing factors, such as insulin resistance, hypoadiponectinemia, inflammation and expansion of visceral adipose tissues. Often increased levels of insulin are found among T2D individuals while the values of insulin could be lower as well in individuals with increased insulin clearance [18]. The proposed hypothesis for NASH is the two-hit to multiple-hit models where, especially in the first hit, lipid infiltrates to liver and second hit involves inflammation [19]. The level of TNFα is increased with increased toll-like receptors (TLR4 and TLR9) agonists in portal circulation after changes in gut microbiota [20]. The process of NAFLD and contributing factors for developing NASH is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The process of development of NAFLD and NASH from normal liver. Adopted from one of our earlier publications on this series (Saghir et al. [159]).

Insulin and activation of transcription factors

Insulin binds to insulin receptor, a tyrosine kinase receptor. The signals are further carried by G-protein coupled receptor by activation of Raf serine/threonine kinases (Raf) which activates the MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) followed by the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK)(Raf/MEK/ERK) and PI3kinase (phosphoinositide 3-kinase)/protein kinase B (also known as Akt), as well as phospholipase C gamma (PLCγ) pathways in target cells [21]. Insulin receptor activation, after binding of insulin, induces biosynthesis of early growth response protein (Egr-1) transcription factor [22] which is activated by ETS Like-1 protein (Elk-1) [23]. In addition to pancreatic β-Islets of Langerhans, Egr-1 activation also occurs in hepatocytes and lack of Egr-1 delays the hepatocyte mitotic progression [24]. Additionally, Elk-1 regulates activator protein-1 (AP-1) transcription factor [25]. Activation of Elk-1, Egr-1 and AP-1 are important in glucose homeostasis [26-28]. Erg-2, also called Krox20, an Elk-1 related transcription factor is also activated in adipocytes, thus insulin plays an important role in regulation of adipogenesis [29].

Insulin-mediated increased transcription of genes from upstream stimulatory factors (USF-1 and USF-2) have been observed [30]. USF binds to E-box (5’-CANNTG-3’) and can synergize to sterol regulatory element binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c) resulting in activation of lipogenic genes [31]. USF regulates gene transcription of fatty acid synthase (FAS) which converts acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA into palmitic acid. FAS gene contains two E-box, one sterol-response element (SRE), and one liver X receptor response element (LXRE) in the proximal promoter [32]. Other genes involved in lipogenesis, such as acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC), ATP-citrate lyase, and mitochondrial glycerol-3-phosphate acyltransferase, also contain E-box and SREBP-1c binding site and are regulated by insulin and nutrients [33]. Posttranslational modification by insulin phosphorylation and nutrients acetylation plays a significant role in activation of genes of fatty acid synthesis by USF [34,35].

SREBP gene produces two active forms, SREBP-1a and SREBP-1c which are involved in regulation of lipogenic genes by binding to SRE (5’-ATCACCCCAC-3’) or its variations. Insulin treatment causes activation of FAS gene which is mediated by SREBP-1c [36,37]. SREBP expression is regulated by LXR and glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3). c-AMP mediated phosphorylation of LXR activates SREBP-1 gene while glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3) phosphorylation of SREBP results in its degradation by ubiquitin ligase [38-40]. Insulin inhibits GSK-3, thus protecting SREBP-1c from its degradation and activating the lipogenic genes. SREBP-1c functions as a negative regulator of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) in liver, the enzyme responsible for gluconeogenesis. Insulin treatment shuts down PEPCK expression, thus blocking gluconeogenesis. It occurs due to the presence of two SRE sites in the proximal promoter of PEPCK [41].

SREBP-1c is the transcription factor activator, which reduces fatty acid synthesis by 50% in SREBP-1c knock out mice, indicating involvement of other transcription factor(s) [42]. The glucose influx by glucose facilitator, GLUT4, after insulin injection results in activation of carbohydrate response-element binding protein (ChREBP) which is another lipogenic transcription factor expressed in both hepatocytes and adipocytes [43-45]. ChREBP is a single gene expressed by alternate promoters producing two isoforms, ChREBPα and ChREBPβ. ChREBP heterodimerizes with Max-like factor X (Mlx) and binds to 5’-CAYGNGNNNNNCNCRTG-3’ [46,47]. ChREBP is retained in cytoplasm by protein 14-3-3 and breaking of the 14-3-3- from ChREBP causes ChREBP to translocate to nucleus and mediate the transcription from carbohydrate response element (ChORE) [43]. ChORE has been identified in ACC, FAS, and SCD [48]. Together with SREBP-1c, ChREBP regulates the lipogenic genes, ChREBP also regulates enzymes of glycolysis and pentose phosphate pathway, thus providing essential intermediates for lipogenesis [48,49].

Insulin mediated enhanced activity of LXR has been observed in primary hepatocytes [50] and two of LXR, LXRα and LXRβ are abundantly present in adipose tissues. LXR is a member of nuclear receptor superfamily and heterodimerizes with 9-cis retinoic acid receptor (RAR) and binds to 5-AGGTCANNNNAGGTCA-3’ and controls insulin-mediated lipogenesis by activating FAS, ACC, and SCD genes [51]. Knock down of LXRα and LXRα/β abolishes the expression of genes of lipogenic processes [50,52]. LXR also activates SREBP and ChREBP, thus activating the process of lipogenesis [53,54].

Modular Structure of Nuclear Receptors

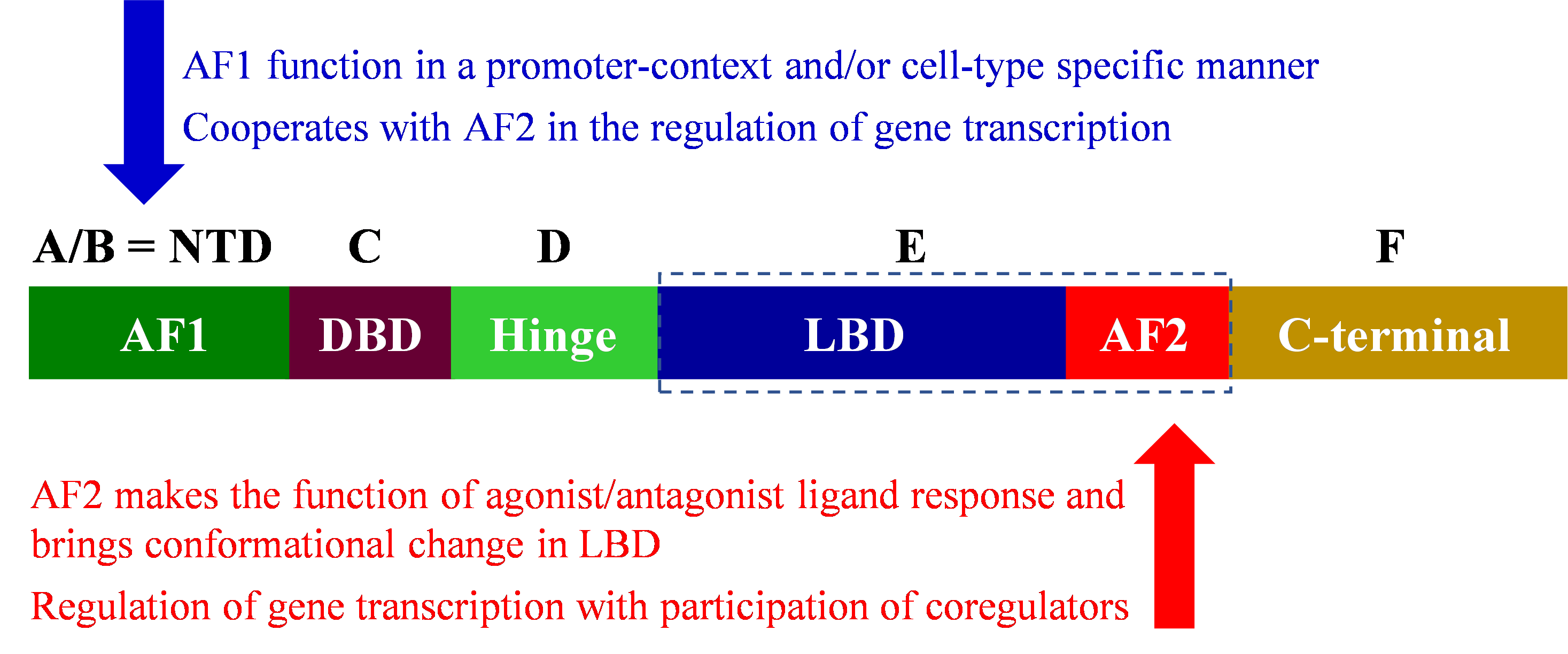

The nuclear receptors (NR) possess a common modular structure which is depicted in Figure 2 [55].

Figure 2. Modular structure of nuclear receptors.

Except for small heterodimer partner (SHP) and dosage-sensitive sex reversal-adrenal hypoplasia congenita critical region on the X chromosome, gene (DAX) (orphan members of the NR), NR possesses six domains from A-F, in some NRs, F domain may be absent. The NH2-terminal domain varies in length and seems highly disorganized when the detailed structure of all 48 receptors of mammalian NRs is examined. The NH2-terminal domain contains activator function-1 (AF-1) which can interact with coregulators in a promoter-specific manner [56]. Variations in NH2-terminal produce isoforms through alternative splicing such as multiple forms of the glucocorticoid receptor (GR), GRB, and GRA [57] and thyroid receptor (TR) [58] while variation in the carboxylic end also produces isoforms such as multiple forms of estrogen receptor-β (ERβ) [59]. Modular structure of selective NRs is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Modular structure of selected nuclear receptors.

Role of PPAR in Lipid Metabolism

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are members of NR superfamily and regulate gene transcription from PPAR response element (PPRE) after binding with metabolic ligand [60]. PPARs are heteromeric partner of retinoid X receptor (RXR) and are unable to bind PPRE as homodimer [60]. PPRE are atypical nuclear hormone receptor binding site, AGGTCA repeat separated by one nucleotide hence referred as direct repeat (DR1) [61]. PPRE contains 5’-extended adenine residues; a consensus PPRE sequence is AACTAGGNCA A AGGTCA [62]. PPARs interact at 5’-sequence while RXR binds at the 3’-sequence. PPAR-RXR also can bind with DR2 element of Rev-erb orphan receptor which can bind to A/T rich sequence in 5’-extension with C and T (DR2) in between AGGTCA repeats. A similar 5’-sequence between PPARE and REV-DR2 sequence opens the possibility of crosstalk between PPARs and Rev-erb [63]. Significant cross talk occurs among the NR members, such as hepatocyte nuclear factor-4 and chicken ovalbumin upstream promoter transcription factor II (HNF4, COUP-TF) and outside of the NR members, nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein 1 (NF-κB, AP-1). These will be described in detail to establish the role of PPARs in lipid, glucose metabolism, energy homeostatis, and inflammation which manifest as atherosclerosis, diabetes, and certain cancers [64].

PPARs were identified as factors responsible for peroxisome proliferation which is the basis of current nomenclature [65]. There are three PPARs (PPARα, PPARβ/δ, and PPARγ) expressed non-uniformly in various body organs [66]. PPARα was identified as intracellular target of clofibrate which is a rodent hepatocarcinogen and causes the proliferation of peroxisome, hence the name PPAR [67]. Clofibrate causes peroxisome proliferation in rodents but clofibrate and other activators of PPARs do not cause peroxisome proliferation in humans [68] as PPARs in human has additional functions such as regulation of genes for the metabolic control [68].

PPARα is expressed in many organs, such as liver, kidney, and heart while PPARδ is widely expressed [69]. PPARγ has limited expression especially in adipose tissues and macrophages which makes PPARγ as the target for treatment of obesity, insulin insensitivity and obesity/insulin insensitivity mediated NAFLD [70]. PPARγ induces adipocyte differentiation and the antidiabetic properties of thiazolidinediones (TZDs) are due to selective activation of adipose resident PPARγ [71]. By differentiating adipose tissue formation, paradoxically, TZDs function as insulin sensitizer although excess adipose tissue and increased deposited fat remains commonly linked to insulin resistance [72]. This discrepancy results in the generation of metabolically dysfunctional adipocytes which start secreting TNFα; the adipocytes undergo enhanced lipolysis due to TNFα-mediated insulin resistance [73]. The enhanced lipolysis causes increased release of free fatty acids which requires to be stored in other body organs, such as liver, resulting into steatosis (hepatosteatosis) and lipotoxicity; these when coupled with inflammatory condition, NASH can lead to cirrhosis and fibrosis [74,75]. PPARγ disrupts the cycle of increased fat by promoting the insulin-sensitive adipose tissue which can sequester free fatty acids reducing potential lipotoxicity in liver and other tissues [73,76]. In response to TZD, PPARγ upregulates fatty acid translocase (also known as cluster of differentiation [CD] CD36), lipoprotein lipase and adipocyte protein 2. All of these upregulated proteins are responsible for lipid uptake in adipose tissues [77,78]. Activation of PPARγ causes upregulation of PEPCK, an enzyme of gluconeogenesis, producing glycerol, which is when esterified with free fatty acids produces intracellular triacylglycerol (lipid) causing free fatty acids mediated lipotoxicity [79,80].

In liver hepatocytes, PPARγ regulates lipid metabolism and carries out de novo lipogenesis (DNL). In response to high fat diet (over nutrition), lipolysis occurs in adipose tissues resulting in hyperlipidemia, forcing the liver to function as secondary fat depot for excess fat [74]. This results in activation of PPARγ which carries out adipogenic transformation of hepatocytes [81,82]. In liver, PPARγ activates adipocyte protein 2, CD36, FAS, and ACC1 which causes accumulation of triacylglycerol in hepatocytes [81,83,84]. PPARγ is adipogenic in hepatocytes, hepatocyte specific knockout of the PPARγ in mice abolishes fat accumulation in livers than wildtype control mice [85,86]. Additionally, PPARγ knockout in ob/ob mice increases circulating free fatty acids while reducing hepatic lipids [84]. This leads to excess fat delivery to other body organs, such as striated muscles, resulting in insulin insensitivity, subsequently developing T2D [84,87]. PPARγ is a two-edge sword, on one edge, it benefits in reducing the lipid accumulation in liver while promoting insulin insensitivity in muscles leading to T2D.

Using the knockout animal model, PPARγ is lipogenic in liver and its agonism creates hepatosteatosis. It is anticipated that increase in PPARγ expression in hepatocytes will increase DNL and is reported among NAFLD patients [82,88]. In clinical trials, however, the PPARγ agonists, rosiglitazone, and pioglitazone, exhibit significant reduction in hepatic fat accumulation which is contrary to the observation in animal studies [89-91].

PPARs activation can down-regulate inflammation. A knockout of PPARα in mice led to prolonged inflammatory response [92]. In rodent model, PPARα ligands, fibrates, negatively regulate the markers of inflammation, such as acute-phase response protein secretion from liver which includes fibrinogen, and C-reactive protein (CRP) [93]. Clinical trial among hyperlipidemic and atherosclerotic patients, fibrate treatment reduces the plasma levels of fibrinogen, CRP, TNFα, and interferon-γ (IFNγ). PPARγ ligands also decrease the production of inflammatory molecules and cytokines from various cells, such as macrophages, dendritic cells, and lymphocytes in addition to epithelial and smooth muscle cells [94,95]. PPARγ ligands treatment finds beneficial effects due to anti-inflammatory effects on obesity-mediated insulin resistance. The down regulation of inflammatory genes, such as CRP, metalloproteinase-9 (MMP9), and TNFα may be the basis of rosiglitazone mediated insulin sensitization effects in humans [96]. Animal knockout of PPARγ demonstrates that these animals become more susceptible to experimentally induced inflammatory bowel disease and arthritis [97,98]. PPARs reduce the inflammatory markers via direct interference with inflammatory transcription factors, such as NF-κB, AP-1, CAAT enhancer binding protein (C/EBP), signal transduction and activation of transcription (STAT), and nuclear factor activator (NF-AT) [64].

Adipose tissues are source of signaling molecules, such as TNFα and adiponectin [99,100]. The putative adiponectin is not well defined; however, adiponectin activates AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) resulting in β-oxidation of fatty acids, compensating the energy needs by reducing gluconeogenesis and insulin insensitivity [101]. Treatment of ob/ob mice with adiponectin reduces hepatic lipid level and TNFα [102]. Therefore, if the levels of adipokines can be increased, it may offer protection against NAFLD. The clinical trial with TZD has reported an increase in adiponectin level and amelioration of hepatosteatosis [103,104]. TZD was found to be a key player in adiponectin null mice which was dependent on adiponectin [105]. One of the animal models for NAFLD is choline-methionine deficient feeding model, studies in this animal model support a direct role of adiponectin in NAFLD [105]. Recombinant adiponectin may differ in glycosylation and therefore in the activity, however, presence of adiponectin in multimeric forms could be the reason of inconsistent results with recombinant adiponectin in treating NAFLD patients [104].

In addition to activation of adiponectin by TZD, PPARγ is also activated which reduced the levels of TNFα from adipose tissues and thus reduced the inflammation. Reduction in TNFα reduced the phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS) at tyrosine, permitting the insulin mediated serine phosphorylation of IRS, thus enhancing insulin activity, and increasing the insulin sensitivity [106]. Activation of PPARγ is beneficial for increasing insulin sensitivity while it increases the adipose tissue, another co-morbidity. Consequently, a PPARγ agonist is needed which can increase the sensitivity of insulin but not stimulate additional storage of fat, i.e., no effect on the body fat level.

Role of Farnesoid X Receptor in Lipid Metabolism

Farnesoid receptors (FXR) are two variants (FXRα and FXRβ) with FXRβ being a pseudogene. Besides liver and intestine, it is also expressed in adipose tissues, adrenal gland, and kidney [107]. FXR plays a central role in bile acid metabolism [107]. FXR regulates genes of lipid, glucose, and lipoprotein metabolism at transcriptional levels. FXR increases nutrients absorption from intestine and activates metabolism of nutrients after meal. The effect is defined as gut:liver axis in the fed state [108]. Ligand mediated activation of FXR reduces hepatosteatosis, inflammation, and fibrogenesis among NAFLD patients. The FXR expressions in liver is decreased among NAFLD patients with concomitant increase in LXR [109,110]. In animal models, 6-ethylchenodeoxycholic acid (OCA) reduces both steatosis and obesity [111]. OCA also decreases hepatosteatosis and obesity among NAFLD patients [112]. A recent clinical trial indicates that activation of FXR by agonist, OCA treatment for 72 weeks of NASH patients improved hepatosteatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis as compared to placebo-treated NASH patients [112]. FXR inhibits SREBP-1c (activated in T2D patients) mediated lipogenesis while activating PPARα [113]. OCA is a synthetic variant with 100-fold higher activity compared with chenodeoxycholic acid which is a natural bile acid [114]. OCA treatment of NASH patients worsened certain parameters, such as cholesterol and HOMA-IR which is a negative observation and does not fit to NAFLD parameters [112]. Hypercholesterolemia was observed with OCA treatment in clinical trial, the FXR ligand obeticholic acid in NASH treatment (FLINT) study [112]. The contrasting benefits require further clinical trials using synthetic ligands. In certain studies, FXR activation has been observed to exacerbate weight increase and glucose intolerance [115,116].

Role of LXR and CAR in Lipid Metabolism

There are two isotypes of LXR: LXRα which is expressed in the liver, kidneys, intestines, adrenal glands, and the lungs and LXRβ (also known as ubiquitous receptor) which can be found nearly in all organs and tissues [117-119]. LXRs contribute to metabolism of various substances including hepatic glucose, lipids, and cholesterol; as a result, they can protect against certain disorders such as atherosclerosis, diabetes, chronic inflammation, Alzheimer disease, cancer, and lipid disorders [120-123]. Endogenous substances such as 27-hydroxycholesterol, 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol, 20(S)-hydroxycholesterol, 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol and 24(S), and 25- epoxy cholesterol, which are oxidative products of cholesterol, can stimulate both LXRα and LXRβ receptors [118,124,125]. LXRs activation will enhance hepatic fatty acid synthesis by promoting expression of the enzymes, fatty acid synthase, ACC1, stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 and also SREBP-1c [53,126,127]. Stimulation of LXRs can also invert cholesterol transports resulting in overall reduction of cholesterol in the body through induction of sterol metabolism and transporter systems like CYP7A1, ATP-binding cassette sub-family A member 1, 5 and 8, and apolipoprotein E [128-130]. LXR stimulators were found to reduce hepatic and blood cholesterol levels and improve glucose tolerance in mice studies; some LXR promoters with single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) like rs35463555 and rs17373080 have showed to regulate sensibility to T2D using human functional and genetic analysis [131].

Constitutive androstane receptor (CAR) is a member of the NR1I3 family, only expressed in liver and functions as xenobiotic nuclear receptor [132]. Although CAR was initially defined as orphan nuclear receptor, ligand binding can lead to nuclear translocation [132]. CAR not only has a fundamental role in the regulation of drug metabolism, but also in energy homeostasis and cancer development by modulating the transcription of its several target genes [133]. Structurally, CAR and typical NRs have similar functional characteristics, including a highly variable N-terminal AF1 domain, a DNA binding domain (DBD), a ligand-binding domain (LBD), and a C-terminal AF2 domain [133].

The effect of CAR on lipid metabolism is controversial. Manty studies have demonstrated that modulation of CAR might lead to changes in hepatic triglyceride levels and therefore, forms an important adverse outcome pathway (AOP) in metabolic effects of xenobiotic compounds [134,135]. In rodent studies, CAR has been identified as a crucial factor in safeguarding against steatosis by inhibiting the production of fats and sugars. Moreover, stimulating CAR activity has been shown to provide protection against fatty liver [136]. Activation of CAR has been linked to improving hepatic steatosis and fatty liver by inhibiting lipogenesis and β-oxidation in high fat diet (HFD)-fed and TCPOBOP-treated mice [137,138]. Treating mice with high levels of lipids using CAR agonists decreases the amount of cholesterol in the liver by promoting its conversion into bile acids. Activation of CAR lowers the levels of bile acids in the bloodstream by increasing the expression of genes responsible for bile acid metabolism and elimination, including CYPs, UGTs, and SULTs [139,140].

Current Clinical Trials for NAFLD

Targeting fat accumulation in liver is the key in the treatment of NAFLD. This can be achieved by blocking fat absorption from intestine, regulating fat metabolism, and/or treating T2D using various drugs. New drugs are developed to achieve the goal of attacking fat accumulation in liver, many are under different phases of preclinical and/or clinical trials (Table 1) for NAFLD and associated diseases. For example, ezetimibe, which inhibits cholesterol absorption at the brush border of the small intestine mediated by the sterol transporter Niemann-Pick C1-Like-1 (NPC1L1), was approved by the FDA in 2022 and now under clinical trial for NAFLD and associated diseases [157]. Drugs targeting fatty acid synthase inhibitors are also under clinical trials to treat NAFLD and associated diseases. T2D treatment by inhibiting sodium glucose type 2 transporter (SGLT2) inhibitors (e.g., dapagliflozin, empagliflozin, tofogliflozin and ipragliflozin) are under trial for NAFLD and associated conditions. Another class of drug which is currently used for T2D treatment which are agonist of glucagon like peptide-1 (GLP-1), such as semaglutide, efinopegdutide, and liraglutide, are also used for weight reduction are under clinical trials for NAFLD and associated diseases. Drugs targeting nuclear receptors especially using fibrates for PPARα (pemafibrate) and PPARγ (-glitazones, such as pioglitazone) are also under clinical trials. Similarly, fibroblast growth factors (FGF), such as FGF21 (pegozafermin) and FGF19 (efruxifermin) analogues are under clinical trials. FGFs are regulators of metabolism and have found application in management of diabetes. Studies demonstrate that FGF21 reduces blood glucose and triglycerides and brings to almost normal levels, the reason used for clinical trials of FGFs for NAFLD. These clinical trials for classes of drugs like SGLT2 inhibitors, PPARs agonists, fatty acid synthase inhibitor, cholesterol absorption inhibitor, FGF agonist, and GLP-1 receptor agonist are summarized in Table 1. Resmetiron has recently been approved by Food and Drug administration (FDA) for the treatment of noncirrhotic and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Resmetirom is a highly selective thyroid hormone receptor-β (TRβ), a nuclear receptor superfamily, agonist. Resmetirom significantly decreases intra-hepatic lipids mainly through increased mitochondrial β oxidation and thus improving hepatocyte mitochondrial function in NASH patients [158].

|

Author |

Design |

Objectives/Endpoints |

Treatment/Intervention |

Outcomes |

|

Flint et al. [141] |

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, two-center, phase 1 clinical, pharmacology trial. |

Primary: change from baseline to week 48 in liver stiffness assessed by MRE.

Secondary: liver steatosis evaluated by MRI-PDFF and the proportion of subjects achieving ≥ 30% reduction in liver fat content from baseline. |

67 were enrolled, 34 of whom were randomized to semaglutide 0.4 mg once daily and 33 to placebo. Of these, 27 subjects (79.4%) receiving semaglutide and 30 subjects (90.9%) receiving placebo completed the trial. and had evaluable 48-week. |

No difference between semaglutide and placebo was seen in the subjects’ liver stiffness.

Reductions in liver steatosis were significantly greater with semaglutide (estimated) and more subjects achieved ≥ 30% reduction in liver fat content with semaglutide at weeks 24, 48 and 72. |

|

Harrison et al. [142] |

Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. |

Relative change in MRI-PDFF assessed hepatic fat compared with placebo at week 12 in patients who had both a baseline and week 12 MRI-PDFF. |

84 patients were randomly assigned 2:1 by a computer-based system to receive resmetirom 80 mg or matching placebo orally once a day. Serial hepatic fat measurements were obtained at weeks 12 and 36, and a second liver biopsy was obtained at week 36. |

Resmetirom-treated patients showed a relative reduction of hepatic fat compared to placebo (at week 12 (–32.9% resmetirom vs –10.4% placebo). |

|

Yoneda et al. [143] |

Open-label, prospective, single-center, randomized clinical. |

Absolute change in MRI-PDFF at 24 weeks. |

40 eligible patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either 20 mg tofogliflozin or 15-30 mg pioglitazone, orally, once daily for 24 weeks. |

Changes in hepatic steatosis after 24 weeks of treatment showed a significant decrease in both groups (–7.54% and –4.12% in the pioglitazone and tofogliflozin groups, respectively). |

|

Hiruma et al. [144] |

Randomized controlled trial. |

Changes in (H-MRS). |

44 patients with T2D and NAFLD were randomly assigned to receive either empagliflozin 10 mg/day or sitagliptin 100 mg/day for 12 weeks. |

IHL decreased more in the empagliflozin (–5.2%) than in the sitagliptin group (–1.9%).

Early administration of SGLT2 inhibitors is preferable for T2D patients with NAFLD. |

|

Romero-Gómez et al. [145] |

Phase IIa, randomized, active-comparator-controlled, parallel-group, open-label study. |

Relative reduction from baseline in LFC (%) after 24 weeks of treatment. |

145 participants were randomized 1:1 to efinopegdutide 10 mg or semaglutide 1 mg subcutaneously once weekly for 24 weeks. |

The relative reduction from baseline in LFC at week 24 was significantly greater with efinopegdutide (72.7%) than semaglutide (42.3%). |

|

Cho et al. [146] |

Open label randomized controlled trial. |

Liver fat change measured as average values in each of nine liver segments by (MRI-PDFF). |

70 participants with confirmed NAFLD were assigned to receive either ezetimibe 10 mg plus rosuvastatin 5 mg daily or rosuvastatin 5 mg for up to 24 weeks. |

Significant reductions from baseline for both combination and monotherapy groups (12.3-18.1% and 12.4-15.0 respectively). Individuals with higher BMI, T2D, insulin resistance, and severe liver fibrosis were good responders to treatment with ezetimibe. |

|

Nakajima et al. [147] |

Double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized multicenter, phase 2 trial. |

Primary: percentage change in MRI-PDFF from baseline to week 24.

Secondary: determination of MRE-based liver stiffness. |

118 patients randomized (1:1) to either 0.2 mg pemafibrate or placebo, orally, twice daily for 72 weeks. |

Nonsignificant difference between the groups in the primary endpoint (–5.3% vs –4.2%). Stiffness, determined by MRE, significantly decreased from placebo at week 48 (difference -5.7%).

Pemafibrate did not decrease liver fat levels but significantly reduced MRE-based liver stiffness. |

|

Loomba et al. [148] |

Phase 2b, multicenter, double-blind, 24-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. |

|

Among the 222 patients who underwent randomization, 219 received subcutaneous pegozafermin (fibroblast growth factor 21 analogue) at a dose of 15 mg or 30 mg weekly or 44 mg once every 2 weeks or placebo weekly or every 2 weeks. |

The percentage of patients who met NASH criteria were 2% in placebo, 37% in 15-mg pegozafermin, 23% in 30-mg pegozafermin group, and 26% in the 44-mg pegozafermin groups.

Pegozafermin improved fibrosis and warrants a phase 3 trial. |

|

Yan et al. [149] |

Open-label, active-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter trial. |

Change in IHL from baseline to week 26 as quantified by MRI-PDFF. |

105 patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive either subcutaneous liraglutide 1.8 mg once daily, oral sitagliptin 100 mg once daily, or subcutaneous insulin glargine at bedtime plus metformin for 26 weeks. |

In the liraglutide and sitagliptin groups, MRI-PDFF significantly decreased from baseline to week 26 (liraglutide, 15.4% to 12.5% and sitagliptin, 15.5% to 11.7%). MRI-PDFF VAT did not change significantly from baseline in the insulin glargine group. MRI-PDFF, VAT in the liraglutide group was significantly higher than in the insulin glargine group (–4.0 vs –0.8), and MRI-PDFF, VAT in the sitagliptin group was also significantly higher than in the insulin glargine group (−3.8 vs. −0.8). |

|

Hameed et al. [150] |

A systematic review and meta-analysis. |

Change in ALT, AST, and GGT and improvement in steatosis and fibrosis. |

Two reviewers searched PubMed, SCOPUS, Cochrane Central, and clinical.trial.s.gov for randomized controlled trials of patients with NAFLD with or without T2D receiving TZDs, and SGLT2 inhibitors. |

Patients from both groups showed improvement in AST (WMD 1.21), ALT (WMD –0.46), GGT (WMD –0.47), and hepatic fibrosis (WMD 0.11). SGLT2 inhibitors, however, resulted in a significant decrease in VFA and body weight. |

|

Takahashi et al. [151] |

Multicenter, open label randomized controlled trial. |

Primary: glycemic control and obesity.

Secondary: hepatic outcomes (including changes in pathological findings between the first and second liver biopsies). |

Participants were given ipragliflozin at a dose of 50 mg once a day and a control group who performed lifestyle modifications, including diet and exercise therapy, and/or took antidiabetic drugs, except for SGLT2, pioglitazone, or GLP-1 analogs, for 72 weeks. |

Ipraglifozin significantly decreased HbA1c, HbA1c did not change from its baseline in control group. None of the participants developed NASH in treatment, 33.3% in control developed NASH. Participants in Ipraglifozin group with NASH at baseline (66.7%) showed resolution without worsening of fibrosis. |

|

Shi et al. [152] |

Prospective, open label, randomized, controlled clinical trial. |

Alterations in (LFC), and pancreatic fat content (PFC) assessed by MRI-PDFF after 24 weeks of treatment, comparing the dapagliflozin group with the control group. |

84 patients with T2D and NAFLD were randomly assigned to receive either dapagliflozin (n = 42) or serve as controls (n = 42). |

At week 24, dapagliflozin group significantly reduced LFC (P<0.001) and PFC (P = 0.033) compared to the control group. |

|

Harrison et al. [153] |

Multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 96-week, phase 2b trial. |

Assess efficacy and safety in patients with NASH and moderate (F2) or severe (F3) fibrosis. |

128 patients were randomly assigned to placebo (n=43), efruxifermin 28 mg (n=42), or efruxifermin 50 mg (n=43). |

In the LBAS (n=113), 8 (20%) of 41 patients in placebo had an improvement in fibrosis of at least 1 stage and no worsening of NASH by week 24 versus 15 (39%) of 38 patients in the efruxifermin 28 mg group, and 14 (41%) of 34 patients in the efruxifermin 50 mg group. |

|

Harrison et al. [154] |

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b study. |

Improvement in liver fibrosis of at least one stage with no worsening of NASH at week 24. |

Patients with biopsy-confirmed NASH and stage 2 or 3 fibrosis were randomly assigned with 1:1:1:1 ratio to receive placebo, aldafermin 0.3 mg, 1 mg, or 3 mg once daily for 24 weeks. |

Aldafermin (analogue of gut hormone fibroblast growth factor 19) was devoid of a significant dose response on fibrosis improvement of at least one stage with no worsening of NASH. |

|

Zhang et al. [155] |

Network meta-analysis. |

Network meta-analysis. |

Electronic databases, including Embase, PubMed and The Cochrane Library, were searched systematically for eligible studies from inception to 20 July 2022. RTCs investigated AST, ALT, and triglyceride levels for PPARα, PPARγ, GLP-1RAs agonist and metformin in patients with NAFLD. |

A total of 22 RCTs involving 1698 eligible patients were analyzed. Both direct and indirect analysis indicated that saroglitazar was significantly superior to GLP-1RAs in improving ALT levels. Metformin effects in improving ALT levels were not as good as saroglitazar. |

|

Loomba et al. [156] |

Randomized, placebo-controlled, single-blind phase 2a trial. |

Safety and relative change in liver fat after treatment. |

Adults with ≥ 8% liver fat, assessed by MRI-PDFF, and evidence of liver fibrosis by MRE ≥ 2.5 kPa or liver biopsy. Ninety-nine patients randomly received either placebo or 25 mg or 50 mg of TVB-2640 (orally, once-daily for 12 weeks). |

Liver fat increased in the placebo cohort by 4.5% than baseline. TVB-2640 reduced liver fat by 9.6% in the 25-mg cohort, and 28.1% in the 50-mg cohort. TVB-2640 significantly reduced liver fat, fibrotic markers, and inflammation after 12 weeks, in a dose-dependent manner in patients with NASH. |

| ALT: Alanine Transaminase; AST: Aspartate Aminotransferase; GGT: Gamma-Glutamyl Transferase; GLP-1Ras: Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists; HbA1c: Hemoglobin A1c; H-MRS: Proton Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy; IHL: Intrahepatic Lipid Content; kPa: Kilopascals; LBAS: Liver Biopsy Analysis Set; LFC: Liver Fat Content; LFMRE: Liver Fibrosis by Magnetic Resonance Elastography; MRE: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; MRI-PDFF: Magnetic Resonance Imaging-Proton Density Fat Fraction; NASH: Non-alcoholic Steatohepatitis; PFC: Pancreatic Fat Content; RCT: Randomized Controlled Trials; T2D: Type-2 Diabetes; VAT: Visceral Adipose Tissue; WMD: Weighted Mean Differences | ||||

Concluding Remarks

NAFLD and NASH incidences are increasing worldwide. The scourge of obesity and T2D is linked to the development of NAFLD which can progress to NASH. There is no effective treatment but only exercise to increase the insulin sensitivity as an attempt to ameliorate T2D to lower the effects of insulin on NAFLD. The other prospects of future remedy could be adiponectin when the putative uniformly active recombinant adiponectin can be identified and produced for treatment. There are other targets for treatment which includes nuclear receptors, especially PPARγ. The prospects of an agonist of PPARγ to be successful include that the agonist is active in liver but is devoid of effects on adipose tissues as PPARγ increases the amounts of adipose tissues and thus exacerbate obesity in the individuals who are already suffering from obesity and its associated effects of NAFLD. Many clinical trials are currently exploring this path for possible treatment of NAFLD and its progression to NASH.

Funding

Supported from Health Professions Division (HPD) grants and President’s award (PFRDG) to Rais A Ansari.

References

2. Powell EE, Wong VW, Rinella M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. The Lancet. 2021 Jun 5;397(10290):2212-24.

3. Huang PL. A comprehensive definition for metabolic syndrome. Disease Models & Mechanisms. 2009 Apr 30;2(5-6):231-7.

4. Luo X, Luo SZ, Xu ZX, Zhou C, Li ZH, Zhou XY, et al. Lipotoxic hepatocyte-derived exosomal miR-1297 promotes hepatic stellate cell activation through the PTEN signaling pathway in metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2021 Apr 14;27(14):1419-34.

5. Fianchi F, Liguori A, Gasbarrini A, Grieco A, Miele L. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) as model of gut–liver axis interaction: From pathophysiology to potential target of treatment for personalized therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2021 Jun 17;22(12):6485.

6. Wynn TA, Barron L. Macrophages: master regulators of inflammation and fibrosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2010 Aug;30(3):245-57.

7. Maher JJ. Alcoholic steatosis and steatohepatitis. Semin Gastrointest Dis. 2002 Jan;13(1):31-9.

8. Malhi H, Guicciardi ME, Gores GJ. Hepatocyte death: a clear and present danger. Physiol Rev. 2010 Jul;90(3):1165-94.

9. Geh D, Anstee QM, Reeves HL. NAFLD-Associated HCC: Progress and Opportunities. J Hepatocell Carcinoma. 2021 Apr 8;8:223-239.

10. Mitra S, De A, Chowdhury A. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic and alcoholic fatty liver diseases. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020 Apr 5;5:16.

11. Dai W, Ye L, Liu A, Wen SW, Deng J, Wu X, et al. Prevalence of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017 Sep;96(39):e8179.

12. Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Jan;15(1):11-20.

13. Duarte N, Coelho IC, Patarrão RS, Almeida JI, Penha-Gonçalves C, Macedo MP. How Inflammation Impinges on NAFLD: A Role for Kupffer Cells. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:984578.

14. Kazankov K, Jørgensen SMD, Thomsen KL, Møller HJ, Vilstrup H, George J, et al. The role of macrophages in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Mar;16(3):145-59.

15. Stojsavljević S, Gomerčić Palčić M, Virović Jukić L, Smirčić Duvnjak L, Duvnjak M. Adipokines and proinflammatory cytokines, the key mediators in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Dec 28;20(48):18070-91.

16. Friedman SL, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Rinella M, Sanyal AJ. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med. 2018 Jul;24(7):908-22.

17. Sanyal AJ. Past, present and future perspectives in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019 Jun;16(6):377-86.

18. Sugiyama S, Jinnouchi H, Hieshima K, Kurinami N, Jinnouchi K, Yoshida A, et al. Potential identification of type 2 diabetes with elevated insulin clearance. NEJM Evidence. 2022 Mar 22;1(4):EVIDoa2100052.

19. Buzzetti E, Pinzani M, Tsochatzis EA. The multiple-hit pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Metabolism. 2016 Aug 1;65(8):1038-48.

20. Khanmohammadi S, Kuchay MS. Toll-like receptors and metabolic (dysfunction)-associated fatty liver disease. Pharmacological Research. 2022 Nov 1;185:106507.

21. Thiel G, Guethlein LA, Rössler OG. Insulin-responsive transcription factors. Biomolecules. 2021 Dec 15;11(12):1886.

22. Harada S, Smith RM, Smith JA, White MF, Jarett L. Insulin-induced egr-1 and c-fos expression in 32D cells requires insulin receptor, Shc, and mitogen-activated protein kinase, but not insulin receptor substrate-1 and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996 Nov 22;271(47):30222-6.

23. Thiel G, Backes TM, Guethlein LA, Rössler OG. Critical Protein–Protein Interactions Determine the Biological Activity of Elk-1, a Master Regulator of Stimulus-Induced Gene Transcription. Molecules. 2021 Oct 11;26(20):6125.

24. Liao Y, Shikapwashya ON, Shteyer E, Dieckgraefe BK, Hruz PW, Rudnick DA. Delayed hepatocellular mitotic progression and impaired liver regeneration in early growth response-1-deficient mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004 Oct 8;279(41):43107-16.

25. Müller I, Endo T, Thiel G. Regulation of AP‐1 activity in glucose‐stimulated insulinoma cells. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 2010 Aug 15;110(6):1481-94.

26. Müller I, Rössler OG, Wittig C, Menger MD, Thiel G. Critical role of Egr transcription factors in regulating insulin biosynthesis, blood glucose homeostasis, and islet size. Endocrinology. 2012 Jul 1;153(7):3040-53.

27. Lesch A, Backes TM, Langfermann DS, Rössler OG, Laschke MW, Thiel G. Ternary complex factor regulates pancreatic islet size and blood glucose homeostasis in transgenic mice. Pharmacological Research. 2020 Sep 1;159:104983.

28. Backes TM, Langfermann DS, Lesch A, Rössler OG, Laschke MW, Vinson C, et al. Regulation and function of AP-1 in insulinoma cells and pancreatic β-cells. Biochemical Pharmacology. 2021 Nov 1;193:114748.

29. Wang W, Huang L, Huang Y, Yin JW, Berk AJ, Friedman JM, et al. Mediator MED23 links insulin signaling to the adipogenesis transcription cascade. Developmental Cell. 2009 May 19;16(5):764-71.

30. Ferre‐D'Amare AR, Pognonec P, Roeder RG, Burley SK. Structure and function of the b/HLH/Z domain of USF. The EMBO Journal. 1994 Jan 1;13(1):180-9.

31. Griffin MJ, Wong RH, Pandya N, Sul HS. Direct interaction between USF and

32. Latasa MJ, Griffin MJ, Moon YS, Kang C, Sul HS. Occupancy and function of the− 150 sterol regulatory element and− 65 E-box in nutritional regulation of the fatty acid synthase gene in living animals. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2003 Aug 1;23(16):5896-907.

33. Wong RH, Sul HS. Insulin signaling in fatty acid and fat synthesis: a transcriptional perspective. Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 2010 Dec 1;10(6):684-91.

34. Wong RH, Chang I, Hudak CS, Hyun S, Kwan HY, Sul HS. A role of DNA-PK for the metabolic gene regulation in response to insulin. Cell. 2009 Mar 20;136(6):1056-72.

35. Wang Y, Viscarra J, Kim SJ, Sul HS. Transcriptional regulation of hepatic lipogenesis. Nature reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2015 Nov;16(11):678-89.

36. Dorotea D, Koya D, Ha H. Recent Insights Into SREBP as a Direct Mediator of Kidney Fibrosis via Lipid-Independent Pathways. Front Pharmacol. 2020 Mar 17;11:265.

37. Foretz M, Pacot C, Dugail I, Lemarchand P, Guichard C, Le Lièpvre X, et al. ADD1/SREBP-1c is required in the activation of hepatic lipogenic gene expression by glucose. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1999 May 1;19(5):3760-8.

38. Bengoechea-Alonso MT, Ericsson J. A phosphorylation cascade controls the degradation of active SREBP1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009 Feb 27;284(9):5885-95.

39. Lu M, Shyy JY. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 is negatively modulated by PKA phosphorylation. American Journal of Physiology-Cell Physiology. 2006 Jun;290(6):C1477-86.

40. Yamamoto T, Shimano H, Inoue N, Nakagawa Y, Matsuzaka T, Takahashi A, et al. Protein kinase A suppresses sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1C expression via phosphorylation of liver X receptor in the liver. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007 Apr 20;282(16):11687-95.

41. Chakravarty K, Wu SY, Chiang CM, Samols D, Hanson RW. SREBP-1c and Sp1 interact to regulate transcription of the gene for phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (GTP) in the liver. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004 Apr 9;279(15):15385-95.

42. Liang G, Yang J, Horton JD, Hammer RE, Goldstein JL, Brown MS. Diminished hepatic response to fasting/refeeding and liver X receptor agonists in mice with selective deficiency of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002 Mar 15;277(11):9520-8.

43. Abdul-Wahed A, Guilmeau S, Postic C. Sweet Sixteenth for ChREBP: Established Roles and Future Goals. Cell Metab. 2017 Aug 1;26(2):324-41.

44. Filhoulaud G, Guilmeau S, Dentin R, Girard J, Postic C. Novel insights into ChREBP regulation and function. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013 May 1;24(5):257-68.

45. Postic C, Dentin R, Denechaud PD, Girard J. ChREBP, a transcriptional regulator of glucose and lipid metabolism. Annu. Rev. Nutr.. 2007 Aug 21;27:179-92.

46. Ma L, Robinson LN, Towle HC. ChREBP• Mlx is the principal mediator of glucose-induced gene expression in the liver. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006 Sep 29;281(39):28721-30.

47. Ma L, Tsatsos NG, Towle HC. Direct role of ChREBP· Mlx in regulating hepatic glucose-responsive genes. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005 Mar 25;280(12):12019-27.

48. Ishii S, IIzuka K, Miller BC, Uyeda K. Carbohydrate response element binding protein directly promotes lipogenic enzyme gene transcription. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004 Nov 2;101(44):15597-602.

49. Baraille F, Planchais J, Dentin R, Guilmeau S, Postic C. Integration of ChREBP-mediated glucose sensing into whole body metabolism. Physiology. 2015 Nov;30(6):428-37.

50. Tobin KA, Ulven SM, Schuster GU, Steineger HH, Andresen SM, Gustafsson JÅ, et al. Liver X receptors as insulin-mediating factors in fatty acid and cholesterol biosynthesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002 Mar 22;277(12):10691-7.

51. Wang B, Tontonoz P. Liver X receptors in lipid signalling and membrane homeostasis. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018 Aug;14(8):452-63.

52. Peet DJ, Turley SD, Ma W, Janowski BA, Lobaccaro JM, Hammer RE, et al. Cholesterol and bile acid metabolism are impaired in mice lacking the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXRα. Cell. 1998 May 29;93(5):693-704.

53. Repa JJ, Liang G, Ou J, Bashmakov Y, Lobaccaro JM, Shimomura I, et al. Regulation of mouse sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c gene (SREBP-1c) by oxysterol receptors, LXRα and LXRβ. Genes & Development. 2000 Nov 15;14(22):2819-30.

54. Cha JY, Repa JJ. The liver X receptor (LXR) and hepatic lipogenesis: the carbohydrate-response element-binding protein is a target gene of LXR. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007 Jan 5;282(1):743-51.

55. Weikum ER, Liu X, Ortlund EA. The nuclear receptor superfamily: A structural perspective. Protein Sci. 2018 Nov;27(11):1876-92.

56. Kumar R, Thompson EB. Transactivation functions of the N-terminal domains of nuclear hormone receptors: protein folding and coactivator interactions. Mol Endocrinol. 2003 Jan;17(1):1-10.

57. Weikum ER, Knuesel MT, Ortlund EA, Yamamoto KR. Glucocorticoid receptor control of transcription: precision and plasticity via allostery. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2017 Mar;18(3):159-74.

58. Sadow PM, Chassande O, Koo EK, Gauthier K, Samarut J, Xu J, et al. Regulation of expression of thyroid hormone receptor isoforms and coactivators in liver and heart by thyroid hormone. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003 May 30;203(1-2):65-75.

59. Zhao C, Dahlman-Wright K, Gustafsson JA. Estrogen receptor beta: an overview and update. Nucl Recept Signal. 2008 Feb 1;6:e003.

60. Grygiel-Górniak B. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and their ligands: nutritional and clinical implications--a review. Nutr J. 2014 Feb 14;13:17.

61. Clarke SD, Thuillier P, Baillie RA, Sha X. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: a family of lipid-activated transcription factors. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999 Oct;70(4):566-71.

62. Desvergne B, Wahli W. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: nuclear control of metabolism. Endocr Rev. 1999 Oct;20(5):649-88.

63. Kassam A, Capone JP, Rachubinski RA. Orphan nuclear hormone receptor RevErbalpha modulates expression from the promoter of the hydratase-dehydrogenase gene by inhibiting peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha-dependent transactivation. J Biol Chem. 1999 Aug 6;274(32):22895-900.

64. Ricote M, Glass CK. PPARs and molecular mechanisms of transrepression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007 Aug;1771(8):926-35.

65. Qi C, Zhu Y, Reddy JK. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors, coactivators, and downstream targets. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2000;32 Spring:187-204.

66. Botta M, Audano M, Sahebkar A, Sirtori CR, Mitro N, Ruscica M. PPAR agonists and metabolic syndrome: an established role?. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2018 Apr 14;19(4):1197.

67. Gonzalez FJ. Fatty Acid Metabolism and Hepatocarcinogenesis: Studies with PPARα-Null Mice, in Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptors: From Basic Science to Clinical Applications. In: Fruchart J, Gotto AM, Paoletti R, Staels B, Catapano AL, Editor. Medical Science Symposia Series. Boston, MA: Springer; 2002.

68. Brown JD, Plutzky J. Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptors as transcriptional nodal points and therapeutic targets. Circulation. 2007 Jan 30;115(4):518-33.

69. Christofides A, Konstantinidou E, Jani C, Boussiotis VA. The role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) in immune responses. Metabolism. 2021 Jan 1;114:154338.

70. Chen H, Tan H, Wan J, Zeng Y, Wang J, Wang H, et al. PPAR-γ signaling in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: Pathogenesis and therapeutic targets. Pharmacol Ther. 2023 May;245:108391.

71. Cantello BC, Cawthorne MA, Cottam GP, Duff PT, Haigh D, Hindley RM, et al. [[. omega.-(Heterocyclylamino) alkoxy] benzyl]-2, 4-thiazolidinediones as potent antihyperglycemic agents. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 1994 Nov;37(23):3977-85.

72. Kahn SE, Hull RL, Utzschneider KM. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2006 Dec 14;444(7121):840-6.

73. Okuno A, Tamemoto H, Tobe K, Ueki K, Mori Y, Iwamoto K, et al. Troglitazone increases the number of small adipocytes without the change of white adipose tissue mass in obese Zucker rats. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1998 Mar 15;101(6):1354-61.

74. Fabbrini E, Sullivan S, Klein S. Obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: biochemical, metabolic, and clinical implications. Hepatology. 2010 Feb;51(2):679-89.

75. Machado MV, Diehl AM. Pathogenesis of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2016 Jun;150(8):1769-77.

76. Tontonoz P, Spiegelman BM. Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of PPARγ. Annu. Rev. Biochem.. 2008 Jul 7;77:289-312.

77. Chui PC, Guan HP, Lehrke M, Lazar MA. PPARγ regulates adipocyte cholesterol metabolism via oxidized LDL receptor 1. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005 Aug 1;115(8):2244-56.

78. Schoonjans K, Peinado‐Onsurbe J, Lefebvre AM, Heyman RA, Briggs M, Deeb S, et al. PPARalpha and PPARgamma activators direct a distinct tissue‐specific transcriptional response via a PPRE in the lipoprotein lipase gene. The EMBO Journal. 1996 Oct 1;15(19):5336-48.

79. Tordjman J, Chauvet G, Quette J, Beale EG, Forest C, Antoine B. Thiazolidinediones block fatty acid release by inducing glyceroneogenesis in fat cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003 May 23;278(21):18785-90.

80. Tordjman J, Khazen W, Antoine B, Chauvet G, Quette J, Fouque F, et al. Regulation of glyceroneogenesis and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase by fatty acids, retinoic acids and thiazolidinediones: potential relevance to type 2 diabetes. Biochimie. 2003 Dec 1;85(12):1213-8.

81. Yu S, Matsusue K, Kashireddy P, Cao WQ, Yeldandi V, Yeldandi AV, et al. Adipocyte-specific gene expression and adipogenic steatosis in the mouse liver due to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ1 (PPARγ1) overexpression. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003 Jan 3;278(1):498-505.

82. Pan X, Wang P, Luo J, Wang Z, Song Y, Ye J, et al. Adipogenic changes of hepatocytes in a high-fat diet-induced fatty liver mice model and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. Endocrine. 2015 Apr;48(3):834-47.

83. Zhang YL, Hernandez-Ono A, Siri P, Weisberg S, Conlon D, Graham MJ, et al. Aberrant hepatic expression of PPARγ2 stimulates hepatic lipogenesis in a mouse model of obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hepatic steatosis. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006 Dec 8;281(49):37603-15.

84. Matsusue K, Haluzik M, Lambert G, Yim SH, Gavrilova O, Ward JM, et al. Liver-specific disruption of PPARγ in leptin-deficient mice improves fatty liver but aggravates diabetic phenotypes. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2003 Mar 1;111(5):737-47.

85. Cordoba-Chacon J. Loss of Hepatocyte‐Specific PPARγ Expression Ameliorates Early Events of Steatohepatitis in Mice Fed the Methionine and Choline‐Deficient Diet. PPAR Research. 2020;2020(1):9735083.

86. Morán‐Salvador E, López‐Parra M, García‐Alonso V, Titos E, Martínez‐Clemente M, González‐Périz A, et al. Role for PPARγ in obesity‐induced hepatic steatosis as determined by hepatocyte‐and macrophage‐specific conditional knockouts. The FASEB Journal. 2011 Aug;25(8):2538-50.

87. Gavrilova O, Haluzik M, Matsusue K, Cutson JJ, Johnson L, Dietz KR, et al. Liver peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ contributes to hepatic steatosis, triglyceride clearance, and regulation of body fat mass. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003 Sep 5;278(36):34268-76.

88. Pettinelli P, Videla LA. Up-regulation of PPAR-γ mRNA expression in the liver of obese patients: an additional reinforcing lipogenic mechanism to SREBP-1c induction. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2011 May 1;96(5):1424-30.

89. Ratziu V, Charlotte F, Bernhardt C, Giral P, Halbron M, LeNaour G, et al. Long‐term efficacy of rosiglitazone in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: results of the fatty liver improvement by rosiglitazone therapy (FLIRT 2) extension trial. Hepatology. 2010 Feb;51(2):445-53.

90. Ratziu V, Giral P, Jacqueminet S, Charlotte F, Hartemann–Heurtier A, Serfaty L, et al. Rosiglitazone for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis: one-year results of the randomized placebo-controlled Fatty Liver Improvement with Rosiglitazone Therapy (FLIRT) Trial. Gastroenterology. 2008 Jul 1;135(1):100-10.

91. Cusi K, Orsak B, Bril F, Lomonaco R, Hecht J, Ortiz-Lopez C, et al. Long-term pioglitazone treatment for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and prediabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized trial. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2016 Sep 6;165(5):305-15.

92. Devchand PR, Keller H, Peters JM, Vazquez M, Gonzalez FJ, Wahli W. The PPARα–leukotriene B4 pathway to inflammation control. Nature. 1996 Nov 7;384(6604):39-43.

93. Kockx M, Gervois PP, Poulain P, Derudas B, Peters JM, Gonzalez FJ, et al. Fibrates Suppress Fibrinogen Gene Expression in Rodents Via Activation of the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor-. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 1999 May 1;93(9):2991-8.

94. Daynes RA, Jones DC. Emerging roles of PPARs in inflammation and immunity. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2002 Oct 1;2(10):748-59.

95. Kostadinova R, Wahli W, Michalik L. PPARs in diseases: control mechanisms of inflammation. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 2005 Dec 1;12(25):2995-3009.

96. Hanefeld M, Haffner SM, Menschikowski M, Koehler C, Temelkova-Kurktschiev T, Wildbrett J, et al. Different effects of acarbose and glibenclamide on proinsulin and insulin profiles in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2002 Mar 1;55(3):221-7.

97. Desreumaux P, Dubuquoy L, Nutten S, Peuchmaur M, Englaro W, Schoonjans K, et al. Attenuation of colon inflammation through activators of the retinoid X receptor (Rxr)/Peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor Γ (Pparγ) heterodimer: A basis for new therapeutic strategies. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2001 Apr 2;193(7):827-38.

98. Setoguchi K, Misaki Y, Terauchi Y, Yamauchi T, Kawahata K, Kadowaki T, et al. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ haploinsufficiency enhances B cell proliferative responses and exacerbates experimentally induced arthritis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2001 Dec 1;108(11):1667-75.

99. Makki K, Froguel P, Wolowczuk I. Adipose tissue in obesity‐related inflammation and insulin resistance: cells, cytokines, and chemokines. International Scholarly Research Notices. 2013;2013(1):139239.

100. Coelho M, Oliveira T, Fernandes R. State of the art paper Biochemistry of adipose tissue: an endocrine organ. Archives of Medical Science. 2013 Mar 1;9(2):191-200.

101. Khoramipour K, Chamari K, Hekmatikar AA, Ziyaiyan A, Taherkhani S, Elguindy NM, et al. Adiponectin: Structure, Physiological Functions, Role in Diseases, and Effects of Nutrition. Nutrients. 2021 Apr 2;13(4):1180.

102. Gamberi T, Magherini F, Modesti A, Fiaschi T. Adiponectin Signaling Pathways in Liver Diseases. Biomedicines. 2018 May 7;6(2):52.

103. Yu JG, Javorschi S, Hevener AL, Kruszynska YT, Norman RA, Sinha M, et al. The effect of thiazolidinediones on plasma adiponectin levels in normal, obese, and type 2 diabetic subjects. Diabetes. 2002 Oct 1;51(10):2968-74.

104. Polyzos SA, Kountouras J, Zavos C, Tsiaousi E. The role of adiponectin in the pathogenesis and treatment of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2010 May;12(5):365-83.

105. Nawrocki AR, Rajala MW, Tomas E, Pajvani UB, Saha AK, Trumbauer ME, et al. Mice lacking adiponectin show decreased hepatic insulin sensitivity and reduced responsiveness to peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ agonists. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006 Feb 3;281(5):2654-60.

106. Hotamisligil GS, Murray DL, Choy LN, Spiegelman BM. Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibits signaling from the insulin receptor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1994 May 24;91(11):4854-8.

107. Jiang L, Zhang H, Xiao D, Wei H, Chen Y. Farnesoid X receptor (FXR): Structures and ligands. Computational and Structural Biotechnology Journal. 2021 Jan 1;19:2148-59.

108. Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear receptors, RXR, and the big bang. Cell. 2014 Mar 27;157(1):255-66.

109. Jiao Y, Lu Y, Li XY. Farnesoid X receptor: a master regulator of hepatic triglyceride and glucose homeostasis. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2015 Jan;36(1):44-50.

110. Yang ZX, Shen W, Sun H. Effects of nuclear receptor FXR on the regulation of liver lipid metabolism in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology International. 2010 Dec;4:741-8.

111. Cipriani S, Mencarelli A, Palladino G, Fiorucci S. FXR activation reverses insulin resistance and lipid abnormalities and protects against liver steatosis in Zucker (fa/fa) obese rats [S]. Journal of Lipid Research. 2010 Apr 1;51(4):771-84.

112. Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, Lavine JE, Van Natta ML, Abdelmalek MF, et al. Farnesoid X nuclear receptor ligand obeticholic acid for non-cirrhotic, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (FLINT): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. The Lancet. 2015 Mar 14;385(9972):956-65.

113. Pineda Torra I, Claudel T, Duval C, Kosykh V, Fruchart JC, Staels B. Bile acids induce the expression of the human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α gene via activation of the farnesoid X receptor. Molecular Endocrinology. 2003 Feb 1;17(2):259-72.

114. Zhang Y, LaCerte C, Kansra S, Jackson JP, Brouwer KR, Edwards JE. Comparative potency of obeticholic acid and natural bile acids on FXR in hepatic and intestinal in vitro cell models. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2017 Dec;5(6):e00368.

115. Watanabe M, Horai Y, Houten SM, Morimoto K, Sugizaki T, Arita E, et al. Lowering bile acid pool size with a synthetic farnesoid X receptor (FXR) agonist induces obesity and diabetes through reduced energy expenditure. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011 Jul 29;286(30):26913-20.

116. Zhang Y, Lee FY, Barrera G, Lee H, Vales C, Gonzalez FJ, et al. Activation of the nuclear receptor FXR improves hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia in diabetic mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006 Jan 24;103(4):1006-11.

117. Whitney KD, Watson MA, Goodwin B, Galardi CM, Maglich JM, Wilson JG, et al. Liver X receptor (LXR) regulation of the LXRα gene in human macrophages. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001 Nov 23;276(47):43509-15.

118. Janowski BA, Grogan MJ, Jones SA, Wisely GB, Kliewer SA, Corey EJ, et al. Structural requirements of ligands for the oxysterol liver X receptors LXRα and LXRβ. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1999 Jan 5;96(1):266-71.

119. Chuu CP, Kokontis JM, Hiipakka RA, Liao S. Modulation of liver X receptor signaling as novel therapy for prostate cancer. Journal of Biomedical Science. 2007 Sep;14:543-53.

120. Xiao L, Xie X, Zhai Y. Functional crosstalk of CAR–LXR and ROR–LXR in drug metabolism and lipid metabolism. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2010 Oct 30;62(13):1316-21.

121. Lee SD, Tontonoz P. Liver X receptors at the intersection of lipid metabolism and atherogenesis. Atherosclerosis. 2015 Sep 1;242(1):29-36.

122. Bonamassa B, Moschetta A. Atherosclerosis: lessons from LXR and the intestine. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2013 Mar 1;24(3):120-8.

123. Ma Z, Deng C, Hu W, Zhou J, Fan C, Di S, et al. Liver X receptors and their agonists: targeting for cholesterol homeostasis and cardiovascular diseases. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2017 Apr;22(1):41-64.

124. Xiao L, Xie X, Zhai Y. Functional crosstalk of CAR–LXR and ROR–LXR in drug metabolism and lipid metabolism. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2010 Oct 30;62(13):1316-21.

125. Janowski BA, Willy PJ, Devi TR, Falck JR, Mangelsdorf DJ. An oxysterol signalling pathway mediated by the nuclear receptor LXRα. Nature. 1996 Oct 24;383(6602):728-31.

126. Joseph SB, Laffitte BA, Patel PH, Watson MA, Matsukuma KE, Walczak R, et al. Direct and indirect mechanisms for regulation of fatty acid synthase gene expression by liver X receptors. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002 Mar 29;277(13):11019-25.

127. Talukdar S, Hillgartner FB. The mechanism mediating the activation of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase-α gene transcription by the liver X receptor agonist T0-901317. Journal of Lipid Research. 2006 Nov 1;47(11):2451-61.

128. Repa JJ, Turley SD, Lobaccaro JM, Medina J, Li L, Lustig K, et al. Regulation of absorption and ABC1-mediated efflux of cholesterol by RXR heterodimers. Science. 2000 Sep 1;289(5484):1524-9.

129. Repa JJ, Berge KE, Pomajzl C, Richardson JA, Hobbs H, Mangelsdorf DJ. Regulation of ATP-binding cassette sterol transporters ABCG5 and ABCG8 by the liver X receptors α and β. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002 May 24;277(21):18793-800.

130. Laffitte BA, Repa JJ, Joseph SB, Wilpitz DC, Kast HR, Mangelsdorf DJ, et al. LXRs control lipid-inducible expression of the apolipoprotein E gene in macrophages and adipocytes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2001 Jan 16;98(2):507-12.

131. Dahlman I, Nilsson M, Gu HF, Lecoeur C, Efendic S, Ostenson CG, et al. Functional and genetic analysis in type 2 diabetes of liver X receptor alleles--a cohort study. BMC Med Genet. 2009 Mar 17;10:27.

132. Yang Z, Danzeng A, Liu Q, Zeng C, Xu L, Mo J, et al. The Role of Nuclear Receptors in the Pathogenesis and Treatment of Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Int J Biol Sci. 2024 Jan 1;20(1):113-126.

133. Yang H, Wang H. Signaling control of the constitutive androstane receptor (CAR). Protein & Cell. 2014 Feb;5(2):113-23.

134. Yan J, Chen B, Lu J, Xie W. Deciphering the roles of the constitutive androstane receptor in energy metabolism. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2015 Jan;36(1):62-70.

135. Mellor CL, Steinmetz FP, Cronin MT. The identification of nuclear receptors associated with hepatic steatosis to develop and extend adverse outcome pathways. Critical Reviews in Toxicology. 2016 Feb 7;46(2):138-52.

136. Marmugi A, Lukowicz C, Lasserre F, Montagner A, Polizzi A, Ducheix S, et al. Activation of the Constitutive Androstane Receptor induces hepatic lipogenesis and regulates Pnpla3 gene expression in a LXR-independent way. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2016 Jul 15;303:90-100.

137. Dong B, Saha PK, Huang W, Chen W, Abu-Elheiga LA, Wakil SJ, et al. Activation of nuclear receptor CAR ameliorates diabetes and fatty liver disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009 Nov 3;106(44):18831-6.

138. Gao J, He J, Zhai Y, Wada T, Xie W. The constitutive androstane receptor is an anti-obesity nuclear receptor that improves insulin sensitivity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2009 Sep 18;284(38):25984-92.

139. Guo GL, Lambert G, Negishi M, Ward JM, Brewer HB, Kliewer SA, et al. Complementary roles of farnesoid X receptor, pregnane X receptor, and constitutive androstane receptor in protection against bile acid toxicity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003 Nov 14;278(46):45062-71.

140. Zhang J, Huang W, Qatanani M, Evans RM, Moore DD. The constitutive androstane receptor and pregnane X receptor function coordinately to prevent bile acid-induced hepatotoxicity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004 Nov 19;279(47):49517-22.

141. Flint A, Andersen G, Hockings P, Johansson L, Morsing A, Sundby Palle M, et al. Randomised clinical trial: semaglutide versus placebo reduced liver steatosis but not liver stiffness in subjects with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Nov;54(9):1150-1161.

142. Harrison SA, Bashir MR, Guy CD, Zhou R, Moylan CA, Frias JP, et al. Resmetirom (MGL-3196) for the treatment of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet. 2019 Nov 30;394(10213):2012-2024.

143. Yoneda M, Honda Y, Ogawa Y, Kessoku T, Kobayashi T, Imajo K, et al. Comparing the effects of tofogliflozin and pioglitazone in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (ToPiND study): a randomized prospective open-label controlled trial. BMJ Open Diabetes Research and Care. 2021 Feb 1;9(1):e001990.

144. Hiruma S, Shigiyama F, Kumashiro N. Empagliflozin versus sitagliptin for ameliorating intrahepatic lipid content and tissue-specific insulin sensitivity in patients with early-stage type 2 diabetes with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A prospective randomized study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2023 Jun;25(6):1576-1588.

145. Romero-Gómez M, Lawitz E, Shankar RR, Chaudhri E, Liu J, Lam RLH, et al. A phase IIa active-comparator-controlled study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of efinopegdutide in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2023 Oct;79(4):888-897.

146. Cho Y, Rhee H, Kim YE, Lee M, Lee BW, Kang ES, et al. Ezetimibe combination therapy with statin for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an open-label randomized controlled trial (ESSENTIAL study). BMC Med. 2022 Mar 21;20(1):93.

147. Nakajima A, Eguchi Y, Yoneda M, Imajo K, Tamaki N, Suganami H, et al. Randomised clinical trial: Pemafibrate, a novel selective peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor α modulator (SPPARMα), versus placebo in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021 Nov;54(10):1263-1277.

148. Loomba R, Sanyal AJ, Kowdley KV, Bhatt DL, Alkhouri N, Frias JP, et al. Randomized, Controlled Trial of the FGF21 Analogue Pegozafermin in NASH. N Engl J Med. 2023 Sep 14;389(11):998-1008.

149. Yan J, Yao B, Kuang H, Yang X, Huang Q, Hong T, et al. Liraglutide, Sitagliptin, and Insulin Glargine Added to Metformin: The Effect on Body Weight and Intrahepatic Lipid in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Hepatology. 2019 Jun;69(6):2414-26.

150. Hameed I, Hayat J, Marsia S, Samad SA, Khan R, Siddiqui OM, et al. Comparison of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and thiazolidinediones for management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2023 May;47(5):102111.

151. Takahashi H, Kessoku T, Kawanaka M, Nonaka M, Hyogo H, Fujii H, et al. Ipragliflozin Improves the Hepatic Outcomes of Patients With Diabetes with NAFLD. Hepatol Commun. 2022 Jan;6(1):120-132.

152. Shi M, Zhang H, Wang W, Zhang X, Liu J, Wang Q, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on liver and pancreatic fat in patients with type 2 diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Diabetes Complications. 2023 Oct;37(10):108610.

153. Harrison SA, Frias JP, Neff G, Abrams GA, Lucas KJ, Sanchez W, et al. Safety and efficacy of once-weekly efruxifermin versus placebo in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (HARMONY): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023 Dec;8(12):1080-93.

154. Harrison SA, Abdelmalek MF, Neff G, Gunn N, Guy CD, Alkhouri N, et al. Aldafermin in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (ALPINE 2/3): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2b trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022 Jul;7(7):603-16.

155. Zhang ZY, Yan Q, Wu WH, Zhao Y, Zhang H, Li J. PPAR-alpha/gamma agonists, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and metformin for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A network meta-analysis. J Int Med Res. 2023 Jun;51(6):3000605231177191.

156. Loomba R, Mohseni R, Lucas KJ, Gutierrez JA, Perry RG, Trotter JF, et al. TVB-2640 (FASN Inhibitor) for the Treatment of Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: FASCINATE-1, a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Phase 2a Trial. Gastroenterology. 2021 Nov;161(5):1475-86.

157. Brar KS. Ezetimibe (Zetia). Med J Armed Forces India. 2004 Oct;60(4):388-9.

158. Sinha RA, Yen PM. Thyroid hormone-mediated autophagy and mitochondrial turnover in NAFLD. Cell Biosci. 2016 Jul 19;6:46.

159. Saghir SA, Abbas A, Alfuraih S, Sharma A, Latimer J, Omidi Y, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Role of PNPLA3 and its association with environmental chemicals. Arch Clin Toxicol. 2024;6(1):21-32.