Abstract

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), a critical regulator of cell growth, metabolism, survival, and actin-cytoskeletal organization, is primarily recognized for its cytoplasmic functions. However, emerging evidence suggests that the mTOR and its constituent partners also localize to the nucleus, where it may play distinct roles in gene expression regulation, chromatin remodeling, and transcriptional control. This review highlights the evolving understanding of nmTORC2 (nuclear mTORC2), with a particular focus on its composition, functional implications, and relevance in cancer biology. Studies have demonstrated that nmTORC1/C2 components, including Raptor, Rictor, and mSIN1, exhibit stimulus-dependent translocation to the nucleus, potentially influencing nuclear signaling pathways. nmTOR may contribute to transcriptional reprogramming, thereby promoting tumor progression and therapeutic resistance. Additionally, its involvement in epigenetic modifications and interactions with nuclear transcriptional machinery suggests broader roles beyond cancer, extending into metabolic disorders and neurodegenerative diseases. Despite these emerging insights, the specific substrates, upstream regulators, and nuclear recruitment mechanisms of mTORC2 remain largely unexplored. Future research should aim to elucidate the mechanistic underpinnings of nmTORC2, investigate its cross-talk with cytoplasmic signaling, and assess its therapeutic potential through selective targeting strategies. Leveraging advanced proteomics, singlecell transcriptomics, and CRISPR-based genome editing will be essential in uncovering the nuclear-specific functions of mTORC2. A deeper understanding of nmTORC2 could unveil novel regulatory mechanisms and therapeutic vulnerabilities, paving the way for innovative treatments in cancer and other diseases.

Keywords

nmTOR, nmSIN1, nRictor, Chromatin, Epigenetics, Transcription

Abbreviations

mTOR: Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin; nmTOR: Nuclear Mechanistic Target of Rapamycin; nmSIN1: Nuclear Stress-activated MAP Kinase Protein-1; mSIN1: Stress-activated MAP Kinase Protein-1; nRictor: Nuclear Rapamycin Insensitive Companion of mTOR; Rictor: Rapamycin Insensitive Companion of mTOR; EGFR: Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor; PI3K: Phosphoinositide-3-kinase; EZH2: Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2; RHEB: Ras Homolog Enriched in Brain; ERK: Extracellular Signal Regulated Kinase; RSK: Ribosomal Protein S6 Kinase; AMPK: AMP-activated Protein Kinase; PP2A: Protein Phosphatase-2; STAT3: Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3; GLUT - Glucose Transporter 1; HK2: Hexokinase 2; PFK-1: Phosphofructokinase-1, SGK: Glucocorticoid-regulated Kinase; PKC: Protein Kinase C; IRS1/2: Insulin-receptor Substrate ½; Grb10: Growth Factor Receptor-bound Protein 10; NDRG1: N-myc Downstream-regulated Gene 1; FoxO: Forkhead box; EGFP: Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein; FRET: Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer; HAT: Histone Acetyltransferase; HDAC: Histone Deacetylase; HMT: Histone Methyltransferase; JMJD1: Jumonji-C Domain-containing; DNMT1: DNA Methyltransferase 1; SAM: S-adenosylmethionine.

Introduction

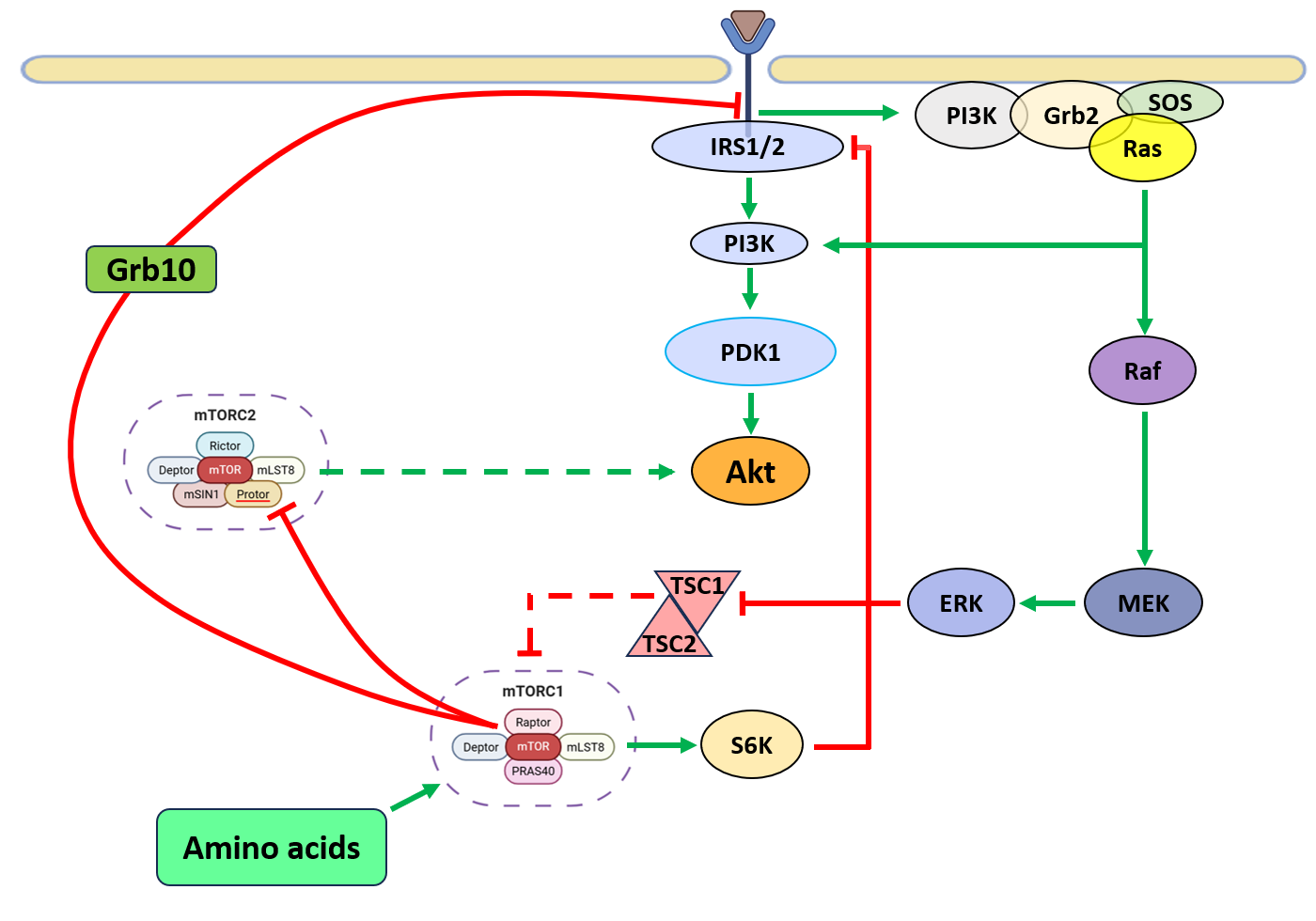

The mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR), a key regulator of cell growth, metabolism, and survival, frequently dysregulated in cancer operates through two distinct multiprotein complexes: mTORC1 and mTORC2 [1]. In cancer, genetic alterations in upstream signaling regulator(s) such as EGFR (Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor), [2] Ras, and PI3K [3] results in hyperactivation of the mTOR pathway. Aberrant mTORC1 and mTORC2 activity promotes tumorigenesis by enhancing anabolic metabolism, inhibiting apoptosis, and conferring therapy resistance [4]. Given its oncogenic potential, mTOR is a prime therapeutic target, with multiple inhibitors (Sapanisertib, Ridaforolimus, TAK-228, AZD2014) under clinical evaluation [5]. The mTORC1 is a central regulator of cellular growth, and proliferation, while mTORC2 controls EMT-associated cell migration and invasion [6], survival by modulating gluconeogenesis [7], cancer metabolic reprogramming and cytoskeletal reorganization [8]. Hyperactive mTOR signaling integrates oncogenic cues to sustain malignant transformation [9]. The PI3K/Akt pathway is a primary mTORC1 activator in cancer, responding to growth factors and insulin signaling [10]. Phosphatidylinositol [3,4,5]-triphosphate (PIP3) facilitates mTORC2 activation, which phosphorylates Akt at Ser473, while phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) phosphorylates Akt at Thr308. Activated Akt promotes tumor growth by inhibiting the TSC1/2 complex, preventing suppression of Ras homolog enriched in brain (RHEB), a direct mTORC1 activator [11-13]. Akt also activates mTORC1 independently of TSC1/2 by phosphorylating PRAS40, an endogenous RAPTOR inhibitor, enhancing oncogenic translation and metabolism [14]. The Ras-MAPK pathway further amplifies mTORC1 signaling by phosphorylating TSC2 via extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) and ribosomal protein S6 kinase (RSK), suppressing TSC1/2 [15,16]. Additionally, RSK-mediated PRAS40 phosphorylation enhances RAPTOR activation, reinforcing mTORC1-driven oncogenic protein synthesis. Canonical mTOR signaling operates within the cytoplasm however, recent reports point towards localization of mTOR and constituent partners to the nuclear sub-compartment [17]. The nuclear localization and potential role as a transcriptional regulator of mTOR have not been fully recognized by the broader mTOR research community [18,19]. While most studies to date have concentrated on mTORC1, particularly in cytoplasmic signaling, the nuclear roles of mTORC2 remain largely uncharacterized. This review aims to highlight the emerging evidence surrounding nmTORC2 (nuclear mTORC2), explore its potential involvement in the regulation of gene expression, and examine its implications in disease development.

Canonical mTOR signaling

mTORC1 signaling

mTOR is closely linked to metabolic reprogramming in cancer [7]. Tumor cells exploit nutrient availability for uncontrolled growth, with mTORC1 sensing amino acids, glucose, ATP, and oxygen. Under energy stress, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) inhibits mTORC1 by promoting TSC1/2 complex formation and phosphorylating RAPTOR, reducing cancer cell proliferation [20,21]. However, many cancers evade this regulation by upregulating pathways that sustain mTORC1 activation despite metabolic deficits. Amino acids, particularly arginine and leucine, activate mTORC1 via the Rag-GTPase complex, recruiting mTORC1 to lysosomes, sustaining oncogenic protein synthesis [22]. Activated mTORC1 enhances the translation of oncogenic proteins. It phosphorylates 4EBP1 and S6K1, releasing eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF-4E) and eukaryotic initiation factor 3 (eIF-3), promoting translation initiation and ribosome biogenesis. These events drive cell cycle progression and uncontrolled proliferation [23,24]. S6K1 also phosphorylates eIF-4B and S6 ribosomal protein (S6RP), sustaining tumor growth [25]. mTORC1 preferentially enhances translation of proteins through ribogenesis [26] (Figure 1). Additionally, it regulates metabolic and survival pathways via hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α), protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A), glycogen synthase, and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), supporting malignant transformation [27]. Consequently, hyperactive mTORC1 enables tumors to evade growth suppression, resist metabolic stress, and drive cancer progression [28,29]. Targeting mTORC1 is a promising oncology strategy, with mTOR inhibitors under investigation to disrupt tumor growth and improve outcomes. While several mTORC1 inhibitors, including rapalogs and ATP-competitive mTOR inhibitors, have been developed and are in clinical use, selective inhibition of mTORC2 remains a significant challenge. Additionally, mTORC1 inhibition either by partial mTOR inhibitors such as rapamycin/rapalogs or by dual inhibitors such as torkinibs are not efficacious as they disrupt mTORC1-dependent inhibitory feedback loops to PI3K [30] and hyperactivate Akt by upregulating mTORC2 signaling [31] (Figures 2 and 3). Therefore, emphasis should be laid on understanding the mTORC2 signaling as recently it has been recently shown to redistribute nuclear sub-compartment [32,33]. Although the precise nuclear functions of mTORC2 remain to be fully elucidated, its subcellular distribution to the nucleus and perinuclear regions suggests a potential target for drug development.

mTORC2 signaling

While mTORC1 regulation is well characterized, mTORC2 remains less understood, particularly in cancer. Its functions are often overshadowed by mTORC1, complicating distinct pathway analysis [34]. Unlike mTORC1, which primarily drives anabolic processes, mTORC2 regulates cytoskeletal organization, survival, cancer metabolic reprogramming, and oncogenic signaling [7] (Figure 1). mTORC2 regulates glycolytic metabolism in cancer through multiple mechanisms. First, it phosphorylates AKT at Ser473, enhancing its activity to: increase glucose transporter (GLUT) expression; activate hexokinase 2 (HK2) for glycolysis initiation; and stimulate phosphofructokinase-1 (PFK-1), a key glycolytic enzyme [35-37]. In Second, mTORC2 modulates glycolysis by regulating c-Myc levels [38], which controls genes involved in glucose uptake and glycolysis—including GLUT1, HK2, PKM2, LDHA, and PDK1—thereby promoting the Warburg effect [39,40]. Third, mTORC2 may suppress gluconeogenic gene transcription in a FoxO-dependent manner [38,41], enhancing metabolic flexibility by rerouting glucose-derived carbons into alternative biosynthetic pathways. Through its essential component, mSIN1, mTORC2 localize at the plasma membrane, interacting with key substrates like Akt, serum and glucocorticoid-regulated kinase (SGK), and protein kinase C (PKC) [42]. The spatial regulation of mTORC2 influences migration, invasion, and therapy resistance. mSIN1 modulates mTORC2 activity, reinforcing sustained Akt signaling, often hyperactivated in cancer. Conversely, S6K1-mediated mSIN1 phosphorylation inhibits mTORC2, representing a negative feedback loop that may be disrupted in tumors [43,44]. Additionally, mSIN1 interacts with the tumor suppressor retinoblastoma protein (Rb) in the cytoplasm, inhibiting mTORC2 complex formation and Akt signaling in MDA-MB-231 cells. Loss of Rb, a frequent event in many cancers, may thus contribute to aberrant mTORC2 activation and tumor progression [45]. Akt, a key oncogenic effector frequently overexpressed in malignancies, integrates PI3K/mTORC2 and PI3K/PDK1 signals to enhance proliferation and survival. Like mTORC2, Akt localization at the plasma membrane is regulated by PIP3, emphasizing the intricate interplay between these pathways. In turn, Akt activation stimulates mTORC1, sustaining tumor progression [13]. Interestingly, mTORC1 negatively regulates mTORC2 through feedback loops modulating oncogenic signaling. One mechanism involves S6K1-mediated degradation of insulin receptor substrate (IRS) 1/2, reducing PI3K/Akt signaling and indirectly inhibiting mTORC2. Another involves growth factor receptor-bound protein 10 (Grb10), an mTORC1 target that negatively regulates PI3K activation [46]. However, these regulatory loops are frequently dysregulated in cancer, sustaining mTORC2 activity and tumor cell survival. mTORC2’s oncogenic role extends beyond Akt to SGK and PKC, key effectors of tumor progression. SGK regulates N-myc downstream-regulated gene 1 (NDRG1) and Forkhead box (FoxO) transcription factors, enhancing survival under metabolic 183 stress or PI3K inhibition [47]. This supports tumor adaptation to hypoxia and nutrient deprivation. Additionally, mTORC2-driven PKC phosphorylation plays a crucial role in cytoskeletal remodeling and cell motility, essential for cancer metastasis [48-51]. By promoting cytoskeletal plasticity, mTORC2 enhances tumor cell invasiveness, contributing to metastatic dissemination.

Evidence of nuclear mTOR

While the cytoplasmic functions of mTOR have been extensively characterized, the role of nmTOR (nuclear mTOR) remains relatively underexplored. Several challenges have hindered widespread acceptance of nmTOR’s functional role. One of the primary issues in the field has been an over-reliance on human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells—a widely used model system that exhibits robust canonical mTOR signaling but demonstrates low levels of nmTOR [52]. Another limitation stems from the fact that many laboratories focused on mTOR signaling have limited expertise in transcriptional mechanisms, leading to biases in experimental design and interpretation. Additionally, early studies investigating mTOR’s nuclear localization were often constrained by variability in cell fractionation protocols, antibody specificity, cell line selection, and the use of overexpressed tagged constructs, which may have led to inconsistent findings [33,53].

Despite these challenges, accumulating evidence over the past two decades strongly supports the presence and activity of mTOR within the nucleus. Several components of both mTORC1 and mTORC2, including Raptor, Rictor, RHEB, SIN1, and S6K, have been detected in the nuclear compartment [52-55]. More recent studies have confirmed that nmTOR plays a direct role in regulating gene transcription. The nuclear localization and transcriptional activity of mTOR have been demonstrated across various organisms, ranging from yeast to humans [32,52-54,56], and have been validated human tumors from different cancer types [57,58]. Notably, genome-wide chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by deep sequencing (ChIP-seq) has identified specific genomic loci bound by nmTOR, further solidifying its role in transcriptional regulation [59]. Advanced imaging techniques, such as fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy (FLIM) to track mTOR-tagged enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) [54] and fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET)-based biosensors to visualize mTOR activity in living cells [60], have provided additional strong evidence of nmTOR localization and function. These findings reinforce the idea that nmTOR is not merely an incidental nuclear resident but an active and integral component of the mTOR signaling pathway.

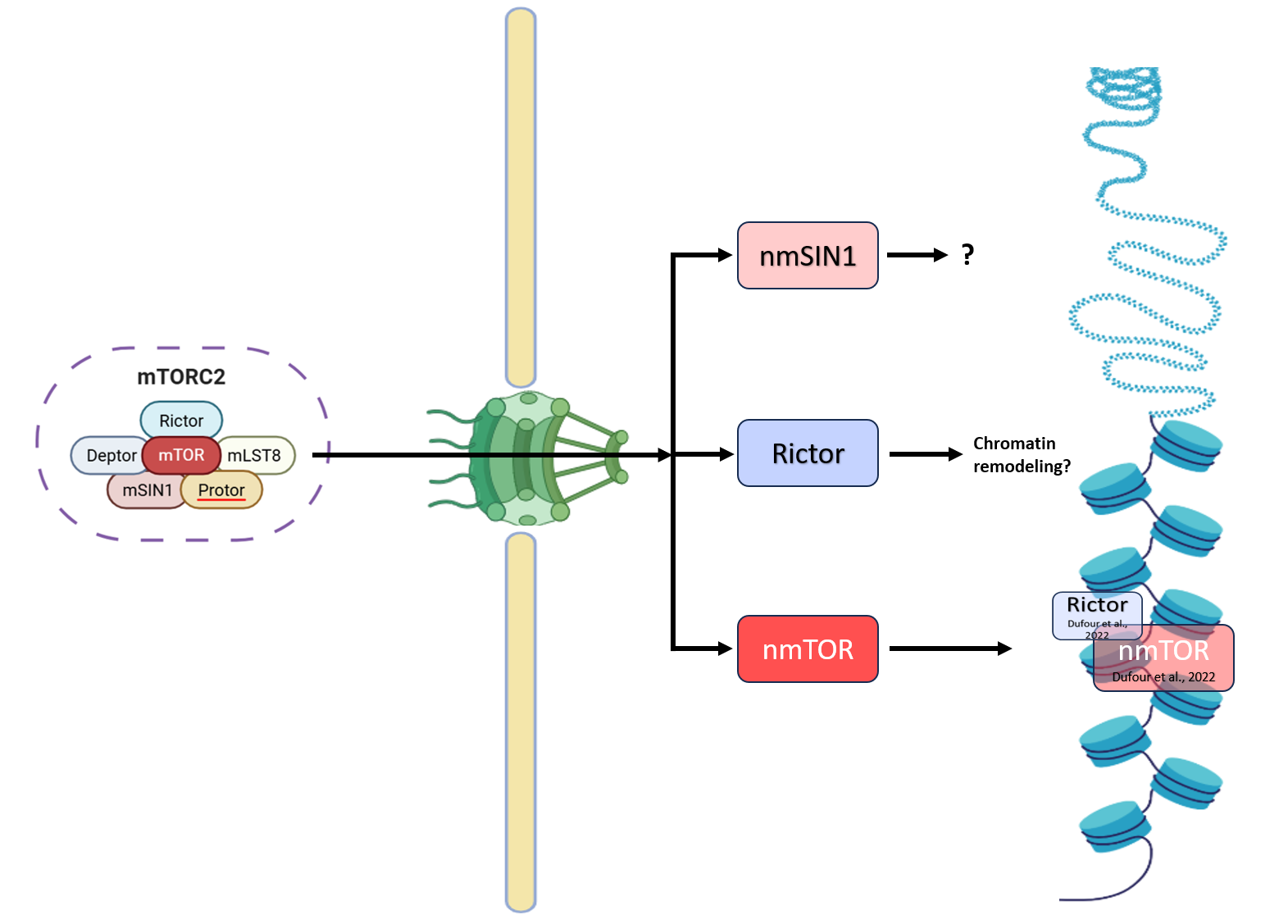

Some studies have reported that components of mTORC2, such as Rictor and mSIN1, can localize to the nucleus and may play a role in regulating gene transcription and chromatin dynamics. Margit Rosner and Markus Hengstschläger (2008) reported that acute rapamycin treatment induced dephosphorylation of mTORC2 components Rictor, and SIN1 specifically in the cytoplasm without disrupting mTORC2 assembly. Chronic exposure led to complete dephosphorylation and relocation of nuclear Rictor (nRictor), and nmSIN1 (nuclear mSIN1) to the cytoplasm, accompanied by inhibited mTORC2 assembly [33]. A pivotal study by Liu and Zheng (2007) investigated the subcellular distribution of mTORC2 components, revealing that while mTOR, mLST8, Rictor, and mSIN1 are more abundant in the cytoplasm, they are also present in the nucleus [61]. The nuclear presence of mSIN1 hints at potential roles in gene expression regulation, DNA repair, or other nuclear processes. Emerging work using advanced imaging techniques and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-based approaches has started to reveal that nmTORC2 might be involved in modulating specific transcriptional programs in cancer cells [57,59]. While the nuclear localization and DNA recruitment of mTOR have been documented, the specific functions of nmTORC2 in gene expression regulation is not known. Studies are required to thoroughly investigate whether nmTORC2 can modulate gene transcription, focusing on its interactions with epigenetic mechanisms and potential transcriptional partners. Additionally, the intrinsic kinase activity of nmTORC2 may directly or indirectly influence the transcriptional machinery and/or the epigenetic landscape of target genes. The mechanisms governing mTORC2's nuclear translocation are equally obscure though it has been known to bind to nuclear pore complex protein which highlights it potential role in nuclear transport mechanisms [57,59]. Understanding these aspects could provide deeper insights into mTORC2's comprehensive functions and reveal novel regulatory pathways that integrate cytoplasmic signaling with nuclear events. Nuclear functions of mTOR are needed to be studied in detail as transcriptional activities and target genes associated with nmTORC2 are influenced by its phosphorylation status, suggesting that these nuclear functions are predetermined by the specific cytoplasmic pathways from which mTORC2 originates. This investigation may delineate the potential regulatory mechanisms of mTORC2's nuclear roles based on their cytoplasmic origins.

Transcriptional Control of Chromatin Remodeling by mTOR Signaling

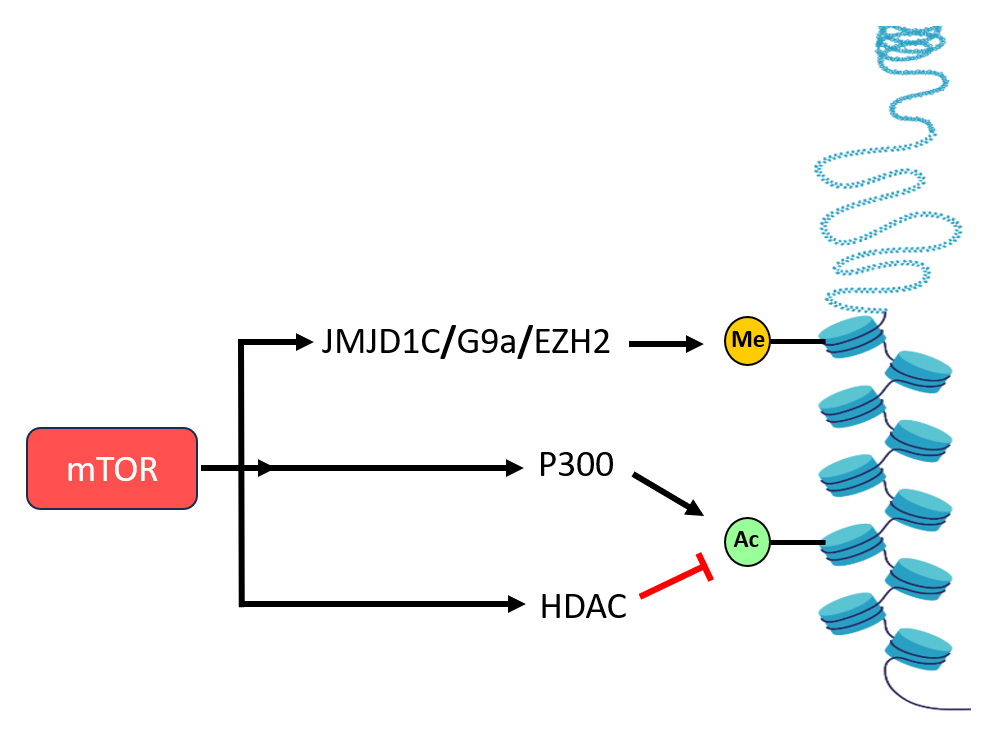

Histone modifications are essential for dynamically regulating gene expression by altering 247 chromatin structure and accessibility [62]. These modifications, primarily methylation and acetylation, are mediated by specific enzyme families, including histone methyltransferases (HMTs), histone demethylases (KDMs), histone acetyltransferases (HATs), and histone deacetylases (HDACs) [63]. Emerging studies have identified mTOR as a key modulator of chromatin dynamics, influencing both epigenetic modifications and transcriptional regulation. One crucial target, Enhancer of Zester 2 (EZH2), functions as the catalytic subunit of the Polycomb repressive complex 2 (PRC2) and is responsible for adding di- and tri-methyl groups to histone H3 at lysine 27 (H3K27me2 and H3K27me3), which are marks of transcriptional repression [64]. EZH2 is frequently overexpressed in multiple cancers, such as breast, prostate, and bladder cancers, making it a target for the anticancer drug tazemetostat. Notably, mTORC1 has been found to elevate EZH2 protein expression, leading to increased H3K27me3 levels and enhanced cell proliferation [65]. Beyond EZH2, mTORC1 also influences histone methylation through its regulation of the histone methyltransferase G9a, which catalyzes the repressive H3K9me2 modification. This regulation suppresses the transcription of autophagy-related genes, thereby inhibiting autophagy and promoting cellular growth [66]. The Jumonji-C domain-containing (JMJD) protein family consists of important histone demethylases involved in transcriptional regulation [67]. Among them, JMJD1C plays a key role in lipid metabolism by demethylating H3K9me2 at the promoters of genes involved in lipogenesis. mTORC1 phosphorylates JMJD1C at T505, facilitating its recruitment to these promoters and thereby promoting lipid biosynthesis [68]. These findings highlight a direct link between mTORC1 and the epigenetic regulation of metabolic processes. Histone acetylation is another crucial epigenetic modification that impacts chromatin accessibility and transcriptional activation [69]. This process is controlled by HATs, which add acetyl groups, and HDACs, which remove them [69]. Studies in yeast have demonstrated that TORC1 modulates histone acetylation through the Esa1 HAT complex and the Rpd3 HDAC [70]. In mammalian cells, mTORC1 phosphorylates S4 of the HAT p300, disrupting its autoinhibitory conformation. This phosphorylation alters p300 activity, reducing autophagy under nutrient deprivation while enhancing lipid biosynthesis [71]. These insights underscore the significant role of mTORC1 in regulating histone acetylation to coordinate metabolic processes.

Chromatin remodeling complexes play a critical role in modulating nucleosome accessibility to transcriptional and coregulatory proteins, thereby shaping gene expression patterns [72]. A key component of the canonical BAF (cBAF) chromatin remodeling complex, AT-rich interaction domain 1A (ARID1A), functions as a tumor suppressor [73]. In hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), ARID1A frequently undergoes genetic alterations, including deletions or nonsense mutations. However, mTORC1 has been shown to regulate ARID1A post-translationally by facilitating its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. This mTORC1–ARID1A interaction promotes oncogenic chromatin remodeling and enhances YAP-dependent transcription, contributing to tumor progression in liver cancer [74]. DNA methylation is another fundamental epigenetic mechanism that influences chromatin organization and gene expression by regulating transcription factor accessibility to DNA. Typically, hypermethylation of gene promoters leads to transcriptional silencing, while hypomethylation can enhance gene activation [75]. Elevated DNA methylation levels, alongside increased mTOR signaling, are associated with poor prognosis in liver cancer patients [76]. Mechanistically, mTORC1 promotes DNA methylation by upregulating DNA methyltransferase 1 (DNMT1) at both the transcriptional and translational levels. Specifically, mTORC1 enhances DNMT1 translation through a 4E-BP1-dependent pathway, further reinforcing oncogenic DNA methylation patterns [77]. Notably, the combined inhibition of mTOR and DNMT1 has been shown to exert a synergistic effect in suppressing HCC growth in both in vitro and in vivo models [77], highlighting the therapeutic potential of targeting mTORC1-driven epigenetic modifications (Figure 4).

Nuclear mTOR at the Intersection of Metabolism and Epigenetics

mTOR serves as a central regulator of metabolic pathways through its influence on epigenetic mechanisms, thereby modulating the supply and utilization of crucial metabolites in glycolysis and the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle. For example, the mTOR–MYC–MAT2A axis governs the production of S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) from methionine and ATP [78]. Additionally, mTOR activation stimulates ATP citrate lyase (ACLY) expression, facilitating acetyl-CoA synthesis via the mTORC1–SREBP signaling pathway [79]. Several key metabolites, such as acetyl-CoA, flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), fumarate, α-ketoglutarate (α-KG), nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), nicotinamide (NAM), and SAM, function as cofactors or substrates for epigenetic enzymes. These molecules not only impact mTORC1 signaling but also contribute to chromatin modifications, thereby establishing regulatory feedback loops that fine-tune gene expression in response to cellular metabolic needs [56,80]. SAM plays a pivotal role as a methyl donor for histone methyltransferases, which modify lysine and arginine residues on histone proteins to regulate gene transcription [81]. Additionally, SAM serves as a substrate for DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs), influencing DNA methylation patterns that dictate gene expression [76]. Interestingly, the SAM-binding protein SAMTOR acts as a negative regulator of mTORC1. When SAM concentrations drop, SAMTOR interacts with GATOR1, leading to mTORC1 inhibition. Conversely, elevated SAM levels disrupt this interaction, triggering mTORC1 activation. This regulatory network connects one-carbon metabolism with mTORC1 signaling, ensuring the synchronization of metabolic and epigenetic processes [82].

Histone demethylation, which counterbalances histone methylation, is tightly regulated by metabolite availability. For instance, FAD is an essential cofactor for histone lysine demethylases (KDMs) such as KDM1A and KDM1B, which utilize FAD-dependent amine oxidation to remove methyl groups from histones. Similarly, α-KG serves as a co-substrate for α-KG-dependent dioxygenases, including Jumonji C (JmjC)-domain-containing histone demethylases (e.g., KDM4 and KDM6), which participate in histone lysine demethylation and DNA cytosine nucleotide modification [83]. Disruptions in the levels of SAM, FAD, or α-KG can interfere with these histone and DNA modifications, ultimately affecting gene expression and cellular function. DNA methylation is also influenced by SAM levels, as DNMT1 and DNMT3A rely on SAM availability. Elevated SAM concentrations have been linked to DNA methylation alterations in lung cancer models, underscoring the metabolic regulation of epigenetics [84]. Additionally, mTORC1 modulates acetyl-CoA levels, which directly influence histone acetylation. Acetyl-CoA acts as a substrate for histone acetyltransferases (HATs), thereby facilitating histone acetylation and modifying chromatin accessibility [85]. ACLY catalyzes the conversion of citrate into acetyl-CoA, supplying the acetyl groups required for histone modifications. Research on human glioblastoma (GBM) has demonstrated that mTORC1 upregulates EZH2, a histone methyltransferase, while mTORC2 is involved in SAM synthesis. Together, these complexes enhance EZH2’s methyltransferase activity, leading to H3K27 hypermethylation and promoting tumor cell survival in both in vitro and in vivo models [85]. This underscores the interplay between mTOR signaling and metabolic-epigenetic interactions in tumor progression.

Nuclear mTORC2: Where Do We Stand?

Critical to mTORC2 specificity, Rictor, and MAPK-interacting protein 1 (mSIN1), form the functional complex [86]. The mSIN1 (MAPKAP1) is critical to mTORC2 as it defines three distinct mTORC2s and is necessary for Akt/PKB phosphorylation [87]. mSIN1 redistribution to nuclear sub-compartment is possibly through c-PKC catalytic activity [88]. Notably, inhibition of protein kinase C (c-PKC) catalytic activity disrupts the nuclear and perinuclear localization of mSIN1 and SGK1, consequently impairing mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation of SGK1 at Ser422 [88]. Recently, Dufour et al., (2022) through chromatin cross-linked mTOR followed by chromatin-immunoprecipitation and LC-MS/MS studies reported Rictor as part of mTOR chromatin-bound interactome along-with chromatin/transcriptional regulators, DNA repair, and protein transport in prostate cancer cells, thus highlighting more direct nuclear functions of Rictor (mTORC2) in these processes [59] (Figure 5). However, the specific functions of nmSN1/nRictor, and how they redistribute to nuclear sub-compartment are not known. Further, whether mTORC2 exist as intact complex within nuclear sub-compartment needs to be explored. Given mSIN1's integral role in mTORC2's stability and substrate specificity, its nuclear localization could be crucial for mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation events within the nucleus, potentially affecting transcription factors or other nuclear proteins.

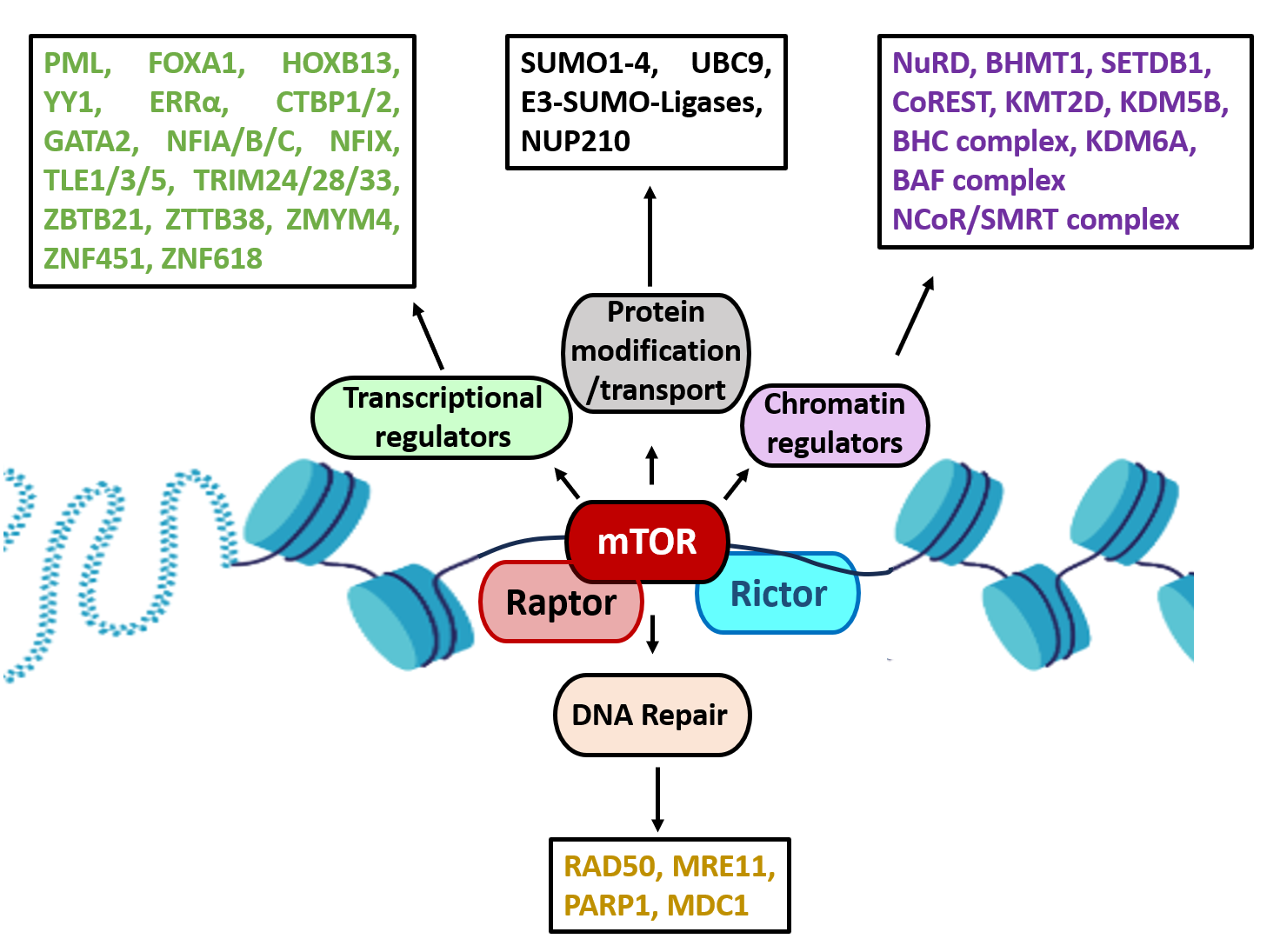

Audet-Walsh et al. (2017) reported that many of the genes involved in the metabolic processes, were identified as direct targets of nmTOR and these findings highlighted nmTOR as crucial metabolic reprogrammer [57]. Additionally, Dufour et al. (2022) reported that the mTOR interactome was highly enriched for factors involved in chromatin remodeling, highlighting a pivotal role for mTOR as a direct regulator of the epigenome [59]. Their study showed that mTOR associates with key components of several chromatin remodeling complexes, including the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase (NuRD) complex, CoREST, the BRAF-HDAC complex (BHC), the BAF complex, and the NCoR/SMRT complex, along with multiple histone modifiers such as the methyltransferases EHMT1, SETDB1, KMT2D, and the demethylases KDM5B and KDM6A. Furthermore, mTOR was found to interact with numerous transcription factors and coregulators, including PML, the pioneer factors FOXA1 and HOXB13, YY1, and the nuclear receptor ERRα (ESRRA), all of which have previously been associated with nmTOR activity. Additional transcriptional interactors identified in the mTOR interactome included C-terminal binding proteins (CTBP1/2), GATA2, nuclear factor 1 proteins (NFIA/B/C, NFIX), transducing-like enhancer proteins (TLE1/3/5), tripartite motif-containing proteins (TRIM24/28/33), and a range of zinc finger proteins such as ZBTB21, ZBTB38, ZMYM4, ZNF451, and ZNF618 [59]. Importantly, the mTOR chromatin interactome was also linked to DNA repair processes, with interactions detected with key repair proteins such as RAD50, MRE11, PARP1, and MDC1, suggesting that mTOR, as a member of the PIKK family, could play a dual role in both transcriptional regulation and DNA repair.

Moreover, the study identified a strong connection between nmTOR–associated proteins and the SUMOylation machinery, including SUMO1–4, the SUMO-conjugating enzyme UBC9 (UBE2I), and E3 SUMO ligases PIAS1–4. Finally, Dufour et al. also identified eight nucleoporins (NUPs), components of the nuclear pore complex, in the mTOR interactome in LNCaP cells. They provided functional evidence that NUP210 directly interacts with mTOR (Figure 6), as shown by co-immunoprecipitation experiments. Notably, partial knockdown of NUP210 in LNCaP cells reduced basal nmTOR levels and prevented R1881-induced nmTOR accumulation. NUP210 knockdown also diminished Torin 1–stimulated nmTOR levels in both LNCaP and PC3 cells, revealing a previously unrecognized mechanism controlling mTOR nuclear trafficking [59].

While the direct nuclear substrates of nmTORC2 remain largely underexplored, several cytoplasmic targets phosphorylated by mTORC2 exert critical indirect nuclear functions following their activation. Notably, mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation of human cGAS (cyclic GMP–AMP synthase, a cytosolic DNA sensor) serine 37 promotes its chromatin localization and regulation of innate immune response in colorectal cancer cells [89]. Recently, Masui et al. (2019) reported that mTORC2 coupled acetyl CoA production with nuclear translocation of histone-modifying enzymes including pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) and class IIa histone deacetylases altering global histone acetylation (H3K9ac, H3K18ac, and H3K27ac) and thus acting as critical epigenetic regulator of iron metabolism and Snail-dependent gene expression [90,91]. mTORC2 controls H3K27 hypermethylation by regulating 37 S-adenosylmethionine production [85]. Additionally, recent studies identified ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY), the enzyme converting citrate to acetyl-CoA, as an mTORC2-AKT-dependent phosphorylation target [91]. This mTORC2-AKT-ACLY axis is critical for stimulating histone acetylation, particularly at histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27ac), a key mark of active enhancers during brown adipocyte differentiation. Consistent with this, promoters of key adipogenic genes display reduced H3K27ac levels in Rictor knockout pre-adipocytes. Thus, mTORC2-mediated phosphorylation of ACLY in the cytoplasm may lead to an overflow of acetyl-CoA directed toward nuclear histone acetylation [91]. SIRT6, which also regulates FoxO1 acetylation [92], has been implicated downstream of mTORC2 in the control of histone H3K56 acetylation (H3K56ac). Loss of mTORC2 in glioma models results in both global and promoter-specific reductions of H3K56Ac at glycolytic gene promoters, accompanied by increased SIRT6 recruitment to these regions [93]. These findings suggest a critical link between mTORC2 and SIRT6 in governing histone acetylation and deacetylation pathways.

In fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe), TORC2 has been implicated in additional layers of epigenetic regulation, particularly in controlling heterochromatin spreading and gene silencing. Genome-wide transcriptional analyses of SpTORC2 or gad8 deletion mutants reveal broad transcriptional defects, including elevated non-coding RNA and subtelomeric gene expression. The transcriptional profiles of these mutants closely resemble those of Clr3 or Clr6 415 mutants—encoding class I and II histone deacetylases, respectively—or mutants of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex RSC [94,95]. These results suggest that SpTORC2 is essential for chromatin-mediated gene silencing and the maintenance of epigenetic states [95]. Using a reporter gene at the mating-type locus, researchers have demonstrated that SpTORC2-Gad8 mutant cells display unstable epigenetic states, stochastically switching between repressed and active configurations [95]. This epigenetic instability may play an important role in cancer development, making it compelling to investigate whether such TORC2 functions are conserved in higher eukaryotes. Heterochromatin is characterized by histone H3 lysine 9 di-methylation (H3K9me2). Subtelomeric regions, adjacent to telomeric repeats, display intermediate levels of H3K9me2, which gradually decline as heterochromatin spreads outward [96]. In SpTORC2-Gad8 mutants, the loss of subtelomeric gene silencing coincides with reduced H3K9me2 spreading, as revealed by genome-wide ChIP analysis [95]. Interestingly, these subtelomeric regions house genes responsive to environmental stress, such as nutrient starvation [97], suggesting that SpTORC2 may regulate adaptive gene expression through chromatin modulation. These indirect nuclear effectors underscore the broader regulatory reach of mTORC2 over nuclear processes, even when the phosphorylation events occur primarily in the cytoplasm. Importantly, they highlight how mTORC2 signaling integrates cytoplasmic activation with nuclear transcriptional and epigenetic regulation, warranting further investigation into potential direct nuclear substrates and mechanisms.

Conclusion

The mTOR signaling pathway has long been recognized as a master regulator of cell growth, metabolism, and survival, primarily through its well-characterized cytoplasmic functions. However, emerging evidence highlights an intriguing nuclear role of mTORC2, expanding its functional repertoire beyond canonical cytoplasmic signaling. Recent studies suggest that nmTORC2 plays a pivotal role in gene expression regulation, chromatin remodeling, and transcriptional control, with implications for both normal cellular physiology and pathological conditions such as cancer. Despite significant advances in understanding cytoplasmic mTORC2 functions, the nuclear-specific mechanisms and interactions remain largely unexplored. Key findings, including the nuclear redistribution of mTORC2 components upon specific stimuli and their association with nuclear proteins involved in transcriptional regulation, suggest a highly dynamic and context-dependent role. However, the precise molecular mechanisms governing nmTORC2 function, including its substrates, binding partners, and regulatory mechanisms, are still being elucidated. Additionally, how nmTORC2 integrates with other signaling networks to modulate gene expression remains an open question. From a clinical perspective, targeting nmTORC2 could present novel therapeutic opportunities, particularly in cancers where dysregulated mTOR signaling contributes to tumor progression and treatment resistance. The differential localization and function of mTORC2 in the nucleus versus the cytoplasm raise the possibility of developing highly specific inhibitors that selectively modulate its nuclear functions without affecting its cytoplasmic roles. However, this requires a more detailed understanding of nmTORC2 interactomes, post-translational modifications, and upstream regulatory signals.

Future Perspectives

Future research on nmTORC2 should focus on several critical areas to uncover its precise molecular mechanisms and therapeutic potential. First, understanding the mechanistic insights into nmTORC2 functions requires identifying its direct nuclear substrates and post-translational modifications. Investigating how mTORC2 is recruited to chromatin and its potential influence on epigenetic modifications is essential, as is elucidating the role of nmSIN1 and other mTORC2 components in transcriptional regulation. Another key area is the cross-talk between cytoplasmic and nmTORC2 signaling, where studies should aim to decipher the signaling cues, such as growth factor stimulation, that drive mTORC2 nuclear translocation and determine whether nmTORC2 functions independently or as an extension of its cytoplasmic counterpart. The pathophysiological relevance of nmTORC2 in cancer and other diseases also demands further exploration, particularly in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), where nuclear signaling alterations are common. Additionally, understanding whether nmTORC2 contributes to resistance mechanisms in targeted therapies and extending research into other diseases, such as metabolic disorders and neurodegeneration, will provide broader insights into its functional significance. From a clinical perspective, therapeutic targeting of nmTORC2 represents an exciting avenue, with efforts needed to develop selective inhibitors that disrupt nmTORC2 while preserving its cytoplasmic functions. Exploring RNA-based therapeutics and targeted protein degradation strategies may provide innovative approaches, while identifying biomarkers reflecting nmTORC2 activity could aid in patient stratification for clinical applications. Existing mTOR inhibitors, such as allosteric inhibitors (rapalogs) and ATP-competitive mTOR kinase inhibitors (TOR-KIs), act non-selectively on both mTORC1 and mTORC2 and fail to specifically target the nuclear-localized fraction of mTOR [98,99]. To selectively target nmTORC2, several strategies can be envisioned: (i) design of nuclear localization signals (NLS) conjugated inhibitors that could allow preferential accumulation in the nucleus, selectively impairing nmTORC2 functions without affecting cytoplasmic complexes; (ii) since mTORC2 components such as mSIN1 or Rictor translocate to the nucleus, inhibitors or peptides that block their nuclear import (e.g., by masking their NLS motifs) or enhance nuclear export might indirectly suppress nmTORC2 activity [100]; (iii) identifying nuclear-specific binding partners or substrates (such as histone-modifying enzymes or chromatin-associated factors) offers the possibility to design inhibitors that block only nmTORC2-dependent interactions, leaving cytoplasmic signaling intact; (iv) given that nmTORC2 regulates histone acetylation (e.g., via acetyl-CoA supply or SIRT6 regulation) [93], combination therapies targeting both mTORC2 and specific epigenetic enzymes (such as histone acetyltransferases or deacetylases) may achieve nuclear-selective effects.

Despite the promising potential of nuclear-selective mTORC2 inhibitors, several key challenges limit their immediate development. First, although the nuclear roles of mTORC2 are increasingly recognized, the exact nuclear-specific substrates and complexes directly regulated by mTORC2 remain poorly characterized, making target prioritization difficult [95]. Additionally, the complexity of compartmentalization poses another obstacle, as many mTORC2 effectors, such as AKT, shuttle between the cytoplasm and nucleus, complicating efforts to disentangle their nuclear versus cytoplasmic contributions to disease phenotypes. Addressing this will require advanced tools such as nuclear-restricted mutants or optogenetic systems. Moreover, the essential nature of mTOR pathways for cell survival and metabolism raises concerns about off-target effects; achieving selective inhibition of the nuclear arm without inducing cytotoxicity or systemic metabolic disruption is a delicate balance [98]. Drug design and delivery also present major hurdles, as developing NLS-tagged inhibitors or peptides that maintain stability, membrane permeability, and favorable pharmacokinetics remains technically challenging and underdeveloped. Finally, a lack of nuclear-specific biomarkers hampers clinical translation; robust biomarkers reflecting nmTORC2 activity —such as nuclear phospho-substrates, histone modification patterns (e.g., H3K56Ac, H3K27Ac), or downstream transcriptional signatures are still lacking [90,93,95,101]. Lastly, technological advancements will be crucial in furthering nmTORC2 research. Advanced proteomics, single-cell transcriptomics, and high-resolution imaging techniques will help map nmTORC2 interactomes, while CRISPR-based genome editing can be employed to dissect its nuclear-specific functions. Additionally, patient-derived organoid models and in vivo approaches will be instrumental in validating the functional and therapeutic relevance of nmTORC2 in disease contexts. In summary, while targeting nmTORC2 offers exciting therapeutic potential, overcoming these challenges will require deeper mechanistic insights, innovative drug design strategies, and the development of reliable nuclear-specific biomarkers for clinical monitoring. Together, these research directions will deepen our understanding of nmTORC2’s role in cellular homeostasis and disease progression, ultimately paving the way for novel therapeutic strategies.

In conclusion, while our understanding of mTORC2 signaling has significantly evolved, its nuclear functions remain a largely uncharted territory with several key questions that largely remain unanswered. First, while nmTORC2 and its constituents redistribute to the nuclear compartment, it remains unclear whether they assemble as intact functional complex inside the nucleus. Clarifying whether nmTORC2 forms functional complex or operates through disassembled constituents will be essential for understanding its nuclear-specific mechanisms. Second, current knowledge of nutrient- and growth factor–mediated activation of TOR kinases is almost exclusively confined to cytoplasmic pathways, particularly those acting at organelle surfaces like vacuoles or lysosomes. How nuclear TOR kinases perceive and respond to upstream signals remains completely unexplored, making this a critical priority for future research. Third, although mTOR possesses intrinsic kinase activity, it is unknown whether nmTORC2 phosphorylates nuclear-localized substrates. One possibility is that nuclear TOR kinases form catalytically active dimeric complexes, akin to their cytoplasmic counterparts, targeting nuclear proteins. Alternatively, if nuclear TOR kinases do not form dimers, the absence of dimeric complexes might increase substrate accessibility to the TOR kinase catalytic site, potentially broadening the range of nuclear substrates. Potential nuclear targets may include components of the RNA polymerase I, II, and III transcriptional machinery, as well as chromatin-modifying enzymes such as the p300 acetyltransferase [71]. Finally, beyond catalytic functions, nmTORC2 and associated subunit such as nRictor, may provide critical scaffolding or non-enzymatic roles in gene regulation. Given their large size, interactions between nmTOR complexes, transcription factors, and chromatin might generate novel regulatory surfaces that recruit additional co-regulators to modulate gene expression. Notably, while the mTOR chromatin-bound interactome has recently been identified [59] no equivalent interactomes exist yet for Rictor or mSIN1. Future studies employing chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with nRictor, nmSIN1, or nmTOR, followed by proteomic and interactome analysis will be essential. Experimental approaches such as blocking nuclear export using inhibitors like leptomycin B (LMB) [100], may also help reveal transient or dynamic nuclear localization events, providing greater precision in studying nuclear functions. Unraveling the complexities of nmTORC2 will not only enhance our fundamental understanding of gene regulation but also pave the way for novel therapeutic strategies in cancer and other diseases. Given its emerging role as a nuclear signaling hub, future research should prioritize dissecting its molecular mechanisms, identifying its functional interactions, and exploring its therapeutic potential. A deeper understanding of nmTORC2 is needed and will ultimately provide valuable insights into the intricate network of cellular signaling and open new avenues for precision medicine approaches.

Competing Interests

The authors hereby declare that they have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Department of Science and Technology – Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB-POWER grant, SPG/2021/002923, GAP0410).

Authors' Contributions

Writing—original manuscript draft Moinuddin and Smrati Bhadauria; Writing—review and editing, Narayan Kumar; Funding acquisition, and supervision— Smrati Bhadauria. All authors have read and agreed to the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Director, CSIR-CDRI for providing the facility/ infrastructure support. The CSIR-CDRI communication number alloted to this article is 11030.

References

2. Tanaka K, Babic I, Nathanson D, Akhavan D, Guo D, Gini B, et al. Oncogenic EGFR Signaling Activates an mTORC2–NF-κB Pathway That Promotes Chemotherapy Resistance. Cancer Discov. 2011 Nov 1;1(6):524-38.

3. Smith SF, Collins SE, Charest PG. Ras, PI3K and mTORC2 – three’s a crowd? J Cell Sci. 2020 Oct 575 1;133(19).

4. Owusu B, Galemmo R, Janetka J, Klampfer L. Hepatocyte Growth Factor, a Key Tumor-Promoting Factor in the Tumor Microenvironment. Cancers (Basel). 2017 Apr 17;9(4):35.

5. Al-Kali A, Aldoss I, Atherton PJ, Strand CA, Shah B, Webster J, et al. A phase 2 and pharmacological study of sapanisertib in patients with relapsed and/or refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Med. 2023 Dec 13;12(23):21229-39.

6. Lamouille S, Connolly E, Smyth JW, Akhurst RJ, Derynck R. TGF-β-induced activation of mTOR complex 2 drives epithelial–mesenchymal transition and cell invasion. Development. 2012 May 15;139(10):e1008-e1008.

7. Khan M, Biswas D, Ghosh M, Mandloi S, Chakrabarti S, Chakrabarti P. mTORC2 controls cancer cell survival by modulating gluconeogenesis. Cell Death Discov. 2015 Sep 7;1(1):15016.

8. Masui K, Cavenee WK, Mischel PS. mTORC2 in the center of cancer metabolic reprogramming. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2014 Jul;25(7):364-73.

9. Kim LC, Cook RS, Chen J. mTORC1 and mTORC2 in cancer and the tumor microenvironment. 89 Oncogene. 2017 Apr 20;36(16):2191-201.

10. Zhang H, Bajraszewski N, Wu E, Wang H, Moseman AP, Dabora SL, et al. PDGFRs are critical for PI3K/Akt activation and negatively regulated by mTOR. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2007 Mar 1;117(3):730-38.

11. Potter CJ, Pedraza LG, Xu T. Akt regulates growth by directly phosphorylating Tsc2. Nat Cell Biol. 2002 Sep 12;4(9):658-65.

12. Manning BD, Tee AR, Logsdon MN, Blenis J, Cantley LC. Identification of the Tuberous Sclerosis Complex-2 Tumor Suppressor Gene Product Tuberin as a Target of the Phosphoinositide 3-Kinase/Akt Pathway. Mol Cell. 2002 Jul;10(1):151-62.

13. Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002 Sep 12;4(9):648-57.

14. Sancak Y, Thoreen CC, Peterson TR, Lindquist RA, Kang SA, Spooner E, et al. PRAS40 Is an Insulin-Regulated Inhibitor of the mTORC1 Protein Kinase. Mol Cell. 2007 Mar;25(6):903-15.

15. Carrière A, Cargnello M, Julien LA, Gao H, Bonneil É, Thibault P, et al. Oncogenic MAPK Signaling Stimulates mTORC1 Activity by Promoting RSK-Mediated Raptor Phosphorylation. Current Biology. 2008 Sep;18(17):1269-77.

16. Ballif BA, Roux PP, Gerber SA, MacKeigan JP, Blenis J, Gygi SP. Quantitative phosphorylation profiling of the ERK/p90 ribosomal S6 kinase-signaling cassette and its targets, the tuberous sclerosis tumor suppressors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005 Jan 18;102(3):667-72.

17. Drenan RM, Liu X, Bertram PG, Zheng XFS. FKBP12-Rapamycin-associated Protein or Mammalian Target of Rapamycin (FRAP/mTOR) Localization in the Endoplasmic Reticulum and the Golgi Apparatus. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004 Jan;279(1):772-8.

18. Li H, Tsang CK, Watkins M, Bertram PG, Zheng XFS. Nutrient regulates Tor1 nuclear localization and association with rDNA promoter. Nature. 2006 Aug 9;442(7106):1058-61.

19. Kim JE, Chen J. Cytoplasmic–nuclear shuttling of FKBP12-rapamycin-associated protein is involved in rapamycin-sensitive signaling and translation initiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2000 Dec 19;97(26):14340-5.

20. Gwinn DM, Shackelford DB, Egan DF, Mihaylova MM, Mery A, Vasquez DS, et al. AMPK Phosphorylation of Raptor Mediates a Metabolic Checkpoint. Mol Cell. 2008 Apr;30(2):214-26.

21. Feng Z, Zhang H, Levine AJ, Jin S. The coordinate regulation of the p53 and mTOR pathways in cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005 Jun 7;102(23):8204-219.

22. Sancak Y, Peterson TR, Shaul YD, Lindquist RA, Thoreen CC, Bar-Peled L, et al. The Rag GTPases Bind Raptor and Mediate Amino Acid Signaling to mTORC1. Science (1979). 2008 Jun 13;320(5882):1496-501.

23. Gingras AC, Kennedy SG, O’Leary MA, Sonenberg N, Hay N. 4E-BP1, a repressor of mRNA translation, is phosphorylated and inactivated by the Akt(PKB) signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 1998 Feb 15;12(4):502-13.

24. Ma XM, Blenis J. Molecular mechanisms of mTOR-mediated translational control. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009 May 2;10(5):307–18.

25. Holz MK, Ballif BA, Gygi SP, Blenis J. mTOR and S6K1 Mediate Assembly of the Translation Preinitiation Complex through Dynamic Protein Interchange and Ordered Phosphorylation Events. Cell. 2005 Nov;123(4):569-80.

26. Hsieh AC, Liu Y, Edlind MP, Ingolia NT, Janes MR, Sher A, et al. The translational landscape of mTOR signalling steers cancer initiation and metastasis. Nature. 2012 May 22;485(7396):55-61.

27. Hudson CC, Liu M, Chiang GG, Otterness DM, Loomis DC, Kaper F, et al. Regulation of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1α Expression and Function by the Mammalian Target of Rapamycin. Mol Cell Biol. 2002 Oct 1;22(20):7004-14.

28. Fingar DC, Salama S, Tsou C, Harlow E, Blenis J. Mammalian cell size is controlled by mTOR and its downstream targets S6K1 and 4EBP1/eIF4E. Genes Dev. 2002 Jun 15;16(12):1472-87.

29. Dowling RJO, Topisirovic I, Alain T, Bidinosti M, Fonseca BD, Petroulakis E, et al. mTORC1-Mediated Cell Proliferation, But Not Cell Growth, Controlled by the 4E-BPs. Science (1979). 2010 May 28;328(5982):1172-6.

30. Rozengurt E, Soares HP, Sinnet-Smith J. Suppression of Feedback Loops Mediated by PI3K/mTOR Induces Multiple Overactivation of Compensatory Pathways: An Unintended Consequence Leading to Drug Resistance. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014 Nov 1;13(11):2477-88.

31. Schroder WA, Buck M, Cloonan N, Hancock JF, Suhrbier A, Sculley T, et al. Human Sin1 contains Ras-binding and pleckstrin homology domains and suppresses Ras signalling. Cell Signal. 2007 Jun;19(6):1279-89.

32. Rosner M, Hengstschläger M. mTOR protein localization is cell cycle-regulated. Cell Cycle. 2011 Oct 15;10(20):3608-10.

33. Rosner M, Hengstschlager M. Cytoplasmic and nuclear distribution of the protein complexes mTORC1 and mTORC2: rapamycin triggers dephosphorylation and delocalization of the mTORC2 components rictor and sin1. Hum Mol Genet. 2008 Jul 9;17(19):2934-48.

34. Upadhyay A. Cancer: An unknown territory; rethinking before going ahead. Genes Dis. 2021 Sep;8(5):655-61.

35. Kohn AD, Summers SA, Birnbaum MJ, Roth RA. Expression of a Constitutively Active Akt Ser/Thr Kinase in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes Stimulates Glucose Uptake and Glucose Transporter 4 Translocation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996 Dec;271(49):31372-8.

36. Gottlob K, Majewski N, Kennedy S, Kandel E, Robey RB, Hay N. Inhibition of early apoptotic events by Akt/PKB is dependent on the first committed step of glycolysis and mitochondrial hexokinase. Genes Dev. 2001 Jun 1;15(11):1406-18.

37. Deprez J, Vertommen D, Alessi DR, Hue L, Rider MH. Phosphorylation and Activation of Heart 6-Phosphofructo-2-kinase by Protein Kinase B and Other Protein Kinases of the Insulin Signaling Cascades. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997 Jul;272(28):17269-75.

38. Masui K, Tanaka K, Akhavan D, Babic I, Gini B, Matsutani T, et al. mTOR Complex 2 Controls Glycolytic Metabolism in Glioblastoma through FoxO Acetylation and Upregulation of c-Myc. Cell Metab. 2013 Nov;18(5):726-39.

39. McFate T, Mohyeldin A, Lu H, Thakar J, Henriques J, Halim ND, et al. Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex Activity Controls Metabolic and Malignant Phenotype in Cancer Cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008 Aug;283(33):22700-8.

40. Dang C V., Le A, Gao P. MYC-Induced Cancer Cell Energy Metabolism and Therapeutic Opportunities. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009 Nov 1;15(21):6479-483.

41. Wang RH, Kim HS, Xiao C, Xu X, Gavrilova O, Deng CX. Hepatic Sirt1 deficiency in mice impairs mTorc2/Akt signaling and results in hyperglycemia, oxidative damage, and insulin resistance. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2011 Nov 1;121(11):4477-90.

42. Liu P, Gan W, Chin YR, Ogura K, Guo J, Zhang J, et al. PtdIns(3,4,5) P 3-Dependent Activation of the mTORC2 Kinase Complex. Cancer Discov. 2015 Nov 1;5(11):1194-209.

43. Yang G, Murashige DS, Humphrey SJ, James DE. A Positive Feedback Loop between Akt and mTORC2 via SIN1 Phosphorylation. Cell Rep. 2015 Aug;12(6):937-43.

44. Liu P, Gan W, Inuzuka H, Lazorchak AS, Gao D, Arojo O, et al. Sin1 phosphorylation impairs mTORC2 complex integrity and inhibits downstream Akt signalling to suppress tumorigenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2013 Nov 27;15(11):1340-50.

45. Zhang J, Xu K, Liu P, Geng Y, Wang B, Gan W, et al. Inhibition of Rb Phosphorylation Leads to mTORC2-Mediated Activation of Akt. Mol Cell. 2016 Jun;62(6):929-42.

46. Yu Y, Yoon SO, Poulogiannis G, Yang Q, Ma XM, Villén J, et al. Phosphoproteomic Analysis 694 Identifies Grb10 as an mTORC1 Substrate That Negatively Regulates Insulin Signaling. Science (1979). 2011 Jun 10;332(6035):1322-6.

47. Weiler M, Blaes J, Pusch S, Sahm F, Czabanka M, Luger S, et al. mTOR target NDRG1 confers 697 MGMT-dependent resistance to alkylating chemotherapy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2014 Jan 7;111(1):409-14.

48. Jacinto E, Loewith R, Schmidt A, Lin S, Rüegg MA, Hall A, et al. Mammalian TOR complex 2 controls the actin cytoskeleton and is rapamycin insensitive. Nat Cell Biol. 2004 Nov 3;6(11):1122-8. 72.

49. Dos D. Sarbassov, Ali SM, Kim DH, Guertin DA, Latek RR, Erdjument-Bromage H, et al. Rictor, a Novel Binding Partner of mTOR, Defines a Rapamycin-Insensitive and Raptor-Independent Pathway that Regulates the Cytoskeleton. Current Biology. 2004 Jul;14(14):1296-302.

50. Thomanetz V, Angliker N, Cloëtta D, Lustenberger RM, Schweighauser M, Oliveri F, et al. Ablation of the mTORC2 component rictor in brain or Purkinje cells affects size and neuron morphology. Journal of Cell Biology. 2013 Apr 15;201(2):293-308.

51. Gan X, Wang J, Wang C, Sommer E, Kozasa T, Srinivasula S, et al. PRR5L degradation promotes 709 mTORC2-mediated PKC-δ phosphorylation and cell migration downstream of Gα12. Nat Cell Biol. 2012 Jul 20;14(7):686-96.

52. Vazquez-Martin A, Cufí S, Oliveras-Ferraros C, Menendez JA. Raptor, a positive regulatory subunit of mTOR complex 1, is a novel phosphoprotein of the rDNA transcription machinery in nucleoli and chromosomal nucleolus organizer regions (NORs). Cell Cycle. 2011 Sep 714 15;10(18):3140-52.

53. Zhang X, Shu L, Hosoi H, Murti KG, Houghton PJ. Predominant Nuclear Localization of Mammalian Target of Rapamycin in Normal and Malignant Cells in Culture. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002 Aug;277(31):28127-34. 718

54. Torres AS, Holz MK. Unraveling the multifaceted nature of the nuclear function of mTOR. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 2021 Feb;1868(2):118907.

55. Laribee RN, Weisman R. Nuclear Functions of TOR: Impact on Transcription and the Epigenome. Genes (Basel). 2020 Jun 10;11(6):641.

56. Chaveroux C, Eichner LJ, Dufour CR, Shatnawi A, Khoutorsky A, Bourque G, et al. Molecular and Genetic Crosstalks between mTOR and ERRα Are Key Determinants of Rapamycin-Induced Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver. Cell Metab. 2013 Apr;17(4):586-98.

57. Audet-Walsh É, Dufour CR, Yee T, Zouanat FZ, Yan M, Kalloghlian G, et al. Nuclear mTOR acts as a transcriptional integrator of the androgen signaling pathway in prostate cancer. Genes Dev. 2017 Jun 15;31(12):1228-42.

58. Audet-Walsh É, Vernier M, Yee T, Laflamme C, Li S, Chen Y, et al. SREBF1 Activity Is Regulated by an AR/mTOR Nuclear Axis in Prostate Cancer. Molecular Cancer Research. 2018 Sep 1;16(9):1396-405.

59. Dufour CR, Scholtes C, Yan M, Chen Y, Han L, Li T, et al. The mTOR chromatin-bound interactome in prostate cancer. Cell Rep. 2022 Mar;38(12):110534.

60. Zhou X, Li S, Zhang J. Tracking the Activity of mTORC1 in Living Cells Using Genetically Encoded FRET-based Biosensor TORCAR. Curr Protoc Chem Biol. 2016 Dec 7;8(4):225-33.

61. Tsang CK, Zheng XFS. TOR-in(g) the Nucleus. Cell Cycle. 2007 Jan 28;6(1):25-9.

62. Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011 Mar 15;21(3):381-95.

63. Black JC, Van Rechem C, Whetstine JR. Histone Lysine Methylation Dynamics: Establishment, Regulation, and Biological Impact. Mol Cell. 2012 Nov;48(4):491-507.

64. Zhao T, Fan J, Abu-Zaid A, Burley S, Zheng XF. Nuclear mTOR Signaling Orchestrates Transcriptional Programs Underlying Cellular Growth and Metabolism. Cells. 2024 May 3;13(9):781.

65. Simon JA, Lange CA. Roles of the EZH2 histone methyltransferase in cancer epigenetics. Mutation Research/Fundamental and Molecular Mechanisms of Mutagenesis. 2008 Dec;647(1-2):21-9.

66. Wei FZ, Cao Z, Wang X, Wang H, Cai MY, Li T, et al. Epigenetic regulation of autophagy by the methyltransferase EZH2 through an MTOR-dependent pathway. Autophagy. 2015 Dec 1;11(12):2309-22.

67. Manni W, Jianxin X, Weiqi H, Siyuan C, Huashan S. JMJD family proteins in cancer and inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022 Sep 1;7(1):304.

68. Viscarra JA, Wang Y, Nguyen HP, Choi YG, Sul HS. Histone demethylase JMJD1C is phosphorylated by mTOR to activate de novo lipogenesis. Nat Commun. 2020 Feb 7;11(1):796.

69. Narita T, Weinert BT, Choudhary C. Functions and mechanisms of non-histone protein 752 acetylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019 Mar 22;20(3):156-74.

70. Rohde JR, Cardenas ME. The Tor Pathway Regulates Gene Expression by Linking Nutrient Sensing to Histone Acetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003 Jan 1;23(2):629-35.

71. Wan W, You Z, Xu Y, Zhou L, Guan Z, Peng C, et al. mTORC1 Phosphorylates Acetyltransferase 756 p300 to Regulate Autophagy and Lipogenesis. Mol Cell. 2017 Oct;68(2):323-35.e6.

72. Centore RC, Sandoval GJ, Soares LMM, Kadoch C, Chan HM. Mammalian SWI/SNF Chromatin 758 Remodeling Complexes: Emerging Mechanisms and Therapeutic Strategies. Trends in Genetics. 2020 Dec;36(12):936-50.

73. Wu JN, Roberts CWM. ARID1A Mutations in Cancer: Another Epigenetic Tumor Suppressor? Cancer Discov. 2013 Jan 1;3(1):35-43.

74. Zhang S, Zhou YF, Cao J, Burley SK, Wang HY, Zheng XFS. mTORC1 Promotes ARID1A Degradation and Oncogenic Chromatin Remodeling in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer Res. 2021 Nov 15;81(22):5652-65.

75. Greenberg MVC, Bourc’his D. The diverse roles of DNA methylation in mammalian development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2019 Oct 9;20(10):590-607.

76. Zeng J deng, Wu WKK, Wang H yun, Li X xing. Serine and one-carbon metabolism, a bridge 768 that links mTOR signaling and DNA methylation in cancer. Pharmacol Res. 2019 Nov;149:104352.

77. Chen M, Fang Y, Liang M, Zhang N, Zhang X, Xu L, et al. The activation of mTOR signalling modulates DNA methylation by enhancing DNMT1 translation in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Transl Med. 2023 Apr 23;21(1):276.

78. Villa E, Sahu U, O’Hara BP, Ali ES, Helmin KA, Asara JM, et al. mTORC1 stimulates cell growth 774 through SAM synthesis and m6A mRNA-dependent control of protein synthesis. Mol Cell. 775 2021 May;81(10):2076-93.e9.

79. Senapati P, Kato H, Lee M, Leung A, Thai C, Sanchez A, et al. Hyperinsulinemia promotes aberrant histone acetylation in triple-negative breast cancer. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2019 Dec 17;12(1):44.

80. Diehl KL, Muir TW. Chromatin as a key consumer in the metabolite economy. Nat Chem Biol. 2020 Jun 22;16(6):620-9.

81. Greer EL, Shi Y. Histone methylation: a dynamic mark in health, disease and inheritance. Nat Rev Genet. 2012 May 3;13(5):343-57.

82. Gu X, Orozco JM, Saxton RA, Condon KJ, Liu GY, Krawczyk PA, et al. SAMTOR is an S -adenosylmethionine sensor for the mTORC1 pathway. Science (1979). 2017 Nov 10;358(6364):813-8.

83. Tran TQ, Lowman XH, Kong M. Molecular Pathways: Metabolic Control of Histone Methylation 790 and Gene Expression in Cancer. Clinical Cancer Research. 2017 Aug 1;23(15):4004-9.

84. Kottakis F, Nicolay BN, Roumane A, Karnik R, Gu H, Nagle JM, et al. LKB1 loss links serine metabolism to DNA methylation and tumorigenesis. Nature. 2016 Nov 17;539(7629):390-5.

85. Harachi M, Masui K, Honda H, Muragaki Y, Kawamata T, Cavenee WK, et al. Dual Regulation of Histone Methylation by mTOR Complexes Controls Glioblastoma Tumor Cell Growth via EZH2 and SAM. Molecular Cancer Research. 2020 Aug 1;18(8):1142-52.

86. Liu GY, Sabatini DM. mTOR at the nexus of nutrition, growth, ageing and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020 Apr 15;21(4):183-203.

87. Frias MA, Thoreen CC, Jaffe JD, Schroder W, Sculley T, Carr SA, et al. mSin1 Is Necessary for Akt/PKB Phosphorylation, and Its Isoforms Define Three Distinct mTORC2s. Current Biology. 2006 Sep;16(18):1865-70.

88. Gleason CE, Oses-Prieto JA, Li KH, Saha B, Situ G, Burlingame AL, et al. Phosphorylation at distinct subcellular locations underlies specificity in mTORC2-mediated activation of SGK1 and Akt. J Cell Sci. 2019 Apr 1;132(7). 804

89. Lv G, Wang Q, Lin L, Ye Q, Li X, Zhou Q, et al. mTORC2-driven chromatin cGAS mediates chemoresistance through epigenetic reprogramming in colorectal cancer. Nat Cell Biol. 2024 Sep 30;26(9):1585-96.

90. Masui K, Harachi M, Ikegami S, Yang H, Onizuka H, Yong WH, et al. mTORC2 links growth factor signaling with epigenetic regulation of iron metabolism in glioblastoma. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2019 Dec;294(51):19740-51.

91. Martinez Calejman C, Trefely S, Entwisle SW, Luciano A, Jung SM, Hsiao W, et al. mTORC2-AKT signaling to ATP-citrate lyase drives brown adipogenesis and de novo lipogenesis. Nat Commun. 2020 Jan 29;11(1):575.

92. Jung SM, Hung CM, Hildebrand SR, Sanchez-Gurmaches J, Martinez-Pastor B, Gengatharan JM, et al. Non-canonical mTORC2 Signaling Regulates Brown Adipocyte Lipid Catabolism through SIRT6-FoxO1. Mol Cell. 2019 Aug;75(4):807-22.e8.

93. Vadla R, Haldar D. Mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) controls glycolytic gene expression by regulating Histone H3 Lysine 56 acetylation. Cell Cycle. 2018 Jan 2;17(1):110-23.

94. Schonbrun M, Laor D, López-Maury L, Bähler J, Kupiec M, Weisman R. TOR Complex 2 Controls Gene Silencing, Telomere Length Maintenance, and Survival under DNA-Damaging Conditions. Mol Cell Biol. 2009 Aug 1;29(16):4584-94.

95. Cohen A, Habib A, Laor D, Yadav S, Kupiec M, Weisman R. TOR complex 2 in fission yeast is required for chromatin-mediated gene silencing and assembly of heterochromatic domains at subtelomeres. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2018 May;293(21):8138-50.

96. Allshire RC, Ekwall K. Epigenetic Regulation of Chromatin States in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015 Jul 1;7(7):a018770.

97. Oya E, Durand-Dubief M, Cohen A, Maksimov V, Schurra C, Nakayama J ichi, et al. Leo1 is essential for the dynamic regulation of heterochromatin and gene expression during cellular quiescence. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2019 Dec 17;12(1):45.

98. Laboucarié T, Detilleux D, Rodriguez-Mias RA, Faux C, Romeo Y, Franz-Wachtel M, et al. TORC1 and TORC2 converge to regulate the SAGA co-activator in response to nutrient availability. EMBO Rep. 2017 Dec 27;18(12):2197-218.

99. Weisman R, Roitburg I, Schonbrun M, Harari R, Kupiec M. Opposite Effects of Tor1 and Tor2 on Nitrogen Starvation Responses in Fission Yeast. Genetics. 2007 Mar 1;175(3):1153-62.

100. Gandhi UH, Senapedis W, Baloglu E, Unger TJ, Chari A, Vogl D, et al. Clinical Implications of Targeting XPO1-mediated Nuclear Export in Multiple Myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2018 May;18(5):335-45.

101. Zhang J, Jia L, Liu T, Yip YL, Tang WC, Lin W, et al. mTORC2-mediated PDHE1α nuclear translocation links EBV-LMP1 reprogrammed glucose metabolism to cancer metastasis in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncogene. 2019 Jun 11;38(24):4669-684.