Abstract

There is striking clinical, histological, and molecular diversity observed across melanocytic tumors. Activating mutations in BRAF and NRAS are well-established initiators of benign melanocytic nevi and melanoma. However, accumulating evidence reveals that the biological outcome after oncogene activation is dependent on cellular state differences that vary by anatomic site, developmental timing, and cell of origin. Recent advances in genomic profiling and functional modeling have demonstrated that melanocytes are not a uniform cell population but exhibit site-specific transcriptional programs and differential transformation competence. Here, we synthesize current evidence from clinical, histological, and genomic studies to highlight the context-dependent effects of BRAF, NRAS, and other oncogenic mutations across melanocytic lesions with particular attention to cutaneous, acral, and mucosal sites.

Keywords

Nevi, Melanoma, Melanocyte, Oncogene, Oncogenic competence

Introduction

Melanocytes, pigment cells of neural crest origin, are responsible for melanin production and epidermal UVR photoprotection [1–3]. While protective against UVR-induced DNA damage [4,5], normal melanocytes at sun-exposed sites exhibit high mutational burden [6]. Evidence suggests that melanocytes or melanocyte stem cells are the cell of origin for both benign melanocytic nevi and melanoma [7]. Cutaneous melanoma accounts for the majority of skin cancer fatalities and prevalence continues to rise [8,9].

At the molecular level, the most common melanocytic tumors, including acquired nevi, congenital nevi, and cutaneous melanoma, are most often initiated through activating mutations in the MAPK pathway, predominantly in BRAF or NRAS genes [10,11]. Nevi are senescent lesions, and malignant transformation from a benign nevus is a rare event that typically requires cooperating alterations such as CDKN2A inactivation, TERT promoter mutations, and/or loss of PTEN or TP53 [12]. Non-BRAF/NRAS driver mutations are commonly found in melanomas from non-cutaneous sites [13].

Competence of Melanocytes to Respond to Oncogene Activation

BRAF or NRAS activating mutations are present in both benign nevi and malignant melanoma. It is thought that BRAF or NRAS mutation in a melanocyte or melanocyte stem cell leads to a period of proliferation followed by senescence, where nevi maintain a stable size over time. There is strong evidence that nevus cells are largely senescent although evidence suggests that a population of non-senescent cells exist within most nevi [14]. The exact mechanisms of senescence in nevi are controversial, with proposed models of oncogene induced senescence, dysfunctional telomere related senescence, and growth arrest by interaction with neighboring cells.

The exact dynamics of growth arrest after BRAFV600E activation are unknown. In a given individual, nevi can vary dramatically in size, suggesting that even in genetically identical backgrounds that cells respond differentially to BRAFV600E activation. In cell culture systems, overexpression of BRAFV600E leads to immediate growth arrest without a proliferative period, while in vivo BRAFV600E leads to nevus formation in zebrafish and mouse models BRAFV600E [7,15,16]. It is likely that expression level plays an important role (i.e. overexpression of BRAF leads to immediate growth arrest while endogenous levels of expression may promote proliferation and nevus formation), as it has been shown in cultured primary human melanocytes that CRISPR/Cas9 introduction of mutant BRAFV600E (at endogenous levels) leads to a gradual growth advantage [17]. It is also possible that melanocytes from a given individual may have differential competence to the same degree of BRAFV600E signaling, and that some melanocytes might immediately undergo growth arrest while others may proliferate and form nevi. Notably, nodular melanoma is an aggressive melanoma variant that only rarely has a nevus associated precursor. It is thought to be caused by oncogene activation in a highly mutated melanocyte or melanocyte stem cell that has acquired the genomic/epigenomic alterations to bypass senescence and respond aggressively to oncogene activation [18].

While acquired melanocytic nevi are benign lesions, they have the capacity to progress to melanoma at a low frequency [19]. At the genetic/genomic level this progression has been well characterized. CDKN2A deletion and TERT promoter lesions are early events found in melanoma in situ, and absent from precursor nevi, while other alterations including mutations of p53 and PI3K (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase) pathway components (including PTEN mutation and deletion) are predominantly found at the stage of invasive melanoma [12,20].

Less common variants of benign melanocytic neoplasms include blue nevi and Spitz nevi, and deep penetrating nevi (DPN) each exhibiting clinical, histological, and genetic/genomic features that are distinct from common acquired nevi. Blue nevi are characterized by high prevalence GNAQ mutations and less commonly activating PKC genomic fusions [21,22]. Spitz nevi are characterized by mutually exclusive fusions in ROS1, NTRK1, ALK, BRAF, and RET [23]. In addition to activating BRAF fusions, activating truncating mutations in MAP3K8 are found in both spitzoid and conventional melanomas, suggesting shared origins and/or biology of these tumor types [24].

How Clinical (Clinical Appearance, Anatomic Distribution) and Histologic Findings of Acquired Nevi Differ with BRAF vs NRAS Mutation

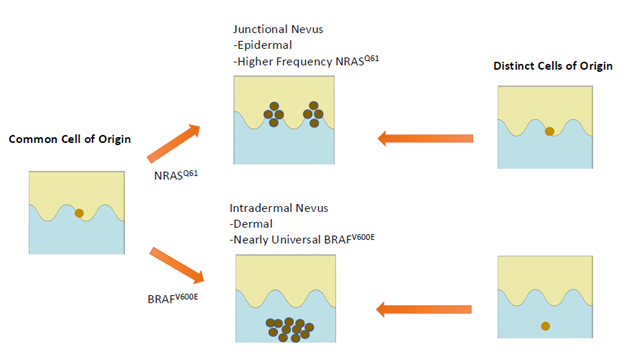

Acquired melanocytic nevi have long been classified histopathologically as junctional, compound, or intradermal. These histologic subtypes correspond to clinical and dermatoscopic features: junctional nevi are flat and exhibit reticular dermatoscopic patterns, while intradermal nevi are raised, often non-pigmented, and exhibit a globular dermatoscopic pattern [25–28]. Emerging evidence suggests molecular differences between these nevus types, including oncogenic mutation spectrum.

Nevi with a globular pattern or peripheral rim of globules (PG), and/or those having intradermal growth pattern almost universally harbor BRAF mutations (92–100%) [25,27,29,30]. Conversely, these same studies show that reticular-patterned nevi and/or nevi with junctional growth pattern more often contain NRAS mutations or lack BRAFV600E mutations (33%), although BRAF mutations are also present in approximately 67% of reticular nevi. These features also correspond to anatomical distribution patterns. BRAF-mutant nevi are more commonly located on the face and trunk, especially in younger individuals, while NRAS-associated reticular nevi show no distinct site preference but predominate in older populations [25,27].

Histologically, BRAF-mutant nevi (especially globular-patterned) typically feature large, well-circumscribed melanocytic nests, periadnexal and perivascular proliferation, and congenital-type features [27,29]. NRAS-mutant nevi, conversely, exhibit lentiginous growth restricted to epidermal ridges, smaller and more irregular nests, and a markedly higher rate of architectural disorder and cytologic atypia [27,30]. Molecularly, reticular nevi display increased copy number alterations (CNAs), loss of heterozygosity (LOH), and greater mutational heterogeneity [31]. Importantly, dysplastic nevi are less likely to exhibit a globular dermatoscopic pattern, and dysplastic nevi demonstrate extensive differential methylation at transcriptionally active loci [32].

How Clinical and Histologic Findings of Giant Congenital Nevi Differ with NRAS vs BRAF Mutation

Congenital melanocytic nevi are present at birth, and are classified based on projected adult size [33]. Giant congenital melanocytic nevi (GCMN) are defined as adult size ≥20cm and these lesions are disfiguring and at greater risk for transformation to melanoma. While it was initially reported that all GCMN are solely due to NRAS mutation, subsequent studies have revealed that BRAFV600E mutations and BRAF activating fusions cause GCMN at a lower frequency, and BRAF/NRAS status impacts melanocytic nevus growth and architecture [34]. The largest studies to date have shown that about 68% of GCMN are due to NRAS mutation, BRAFV600E in 7%, and approximately 7% with activating BRAF genomic fusions [34,35].

While in acquired nevi BRAF mutations lead to only a brief period of proliferation, in GCMN their presence defines a more dynamic, hyperproliferative pathway of development. BRAF-mutant GCMN usually have a multinodular appearance: numerous small, closely packed nodules of the same size with a hard, mobile center within a softer mass [35]. Additionally, BRAF fusion rearrangements are associated with intense pruritus, hyperproliferation, and the development of satellite lesions to mucosal sites such as the oral cavity [36–38]. Interestingly, in GCMN patients having the largest lesions (predicted adult size (PAS) >60 cm), NRAS mutations were overrepresented (91% of cases). As larger lesions are thought to form earlier during development, this suggests the possibility that non-NRAS driver mutations are not tolerated during early embryogenesis [35]. Interestingly, two case reports have linked ALK and NRTK1 fusions (common drivers in Spitz nevi) as rare drivers of congenital nevi; these lesions were BRAF/NRAS negative and exhibited aggressive clinical features of proliferation and or melanoma formation [39,40].

Histologically, BRAF-mutant lesions show an abnormal growth pattern characterized by the subcutaneous infiltrations of nevus cells in adipose tissue in a string-like formation between adipocytes [41]. Immunohistochemical staining has intense cytoplasmic expression of BRAFV600E, which demonstrates clonal proliferation [35]. Invasive growth into deeper tissues, large numbers of nests, and higher Ki-67 proliferation indices of BRAF-positive lesions are shown, compared to their BRAF-negative counterparts, reflecting augmented mitotic activity. Conversely, NRAS-mutant GCMNs, exhibit disordered pigmentation, varied hairiness, surface irregularities, and asymmetric margins, without consistent architectural characteristics that would be suggestive of mutation status [37,42].

GCMN are associated at a low frequency with serious extracutaneous abnormalities, including neurological involvement, typical facial features, and endocrine disturbance [35]. Interestingly, both Polubothu et al. and Zhao et al. did not identify dissimilarities in the incidence of congenital neurological anomalies or melanoma development by mutation type.

Anatomical Niches and Divergent Mutational Landscapes: Nevi versus Melanoma across Cutaneous, Acral, and Mucosal Sites

When compared to cutaneous sites, which are driven by BRAF and NRAS mutations, other anatomic locations, are associated with distinct mutational landscapes of both benign nevi and malignant melanoma [22,43–45].

Acral sites

Melanocytic lesions from acral sites (soles, palms, nail beds) have a characteristic molecular profile. Acral nevi, while still most frequently BRAF-mutant (66.7%), have a broader mutational spectrum, such as GNAQ, KIT, NRAS, and NF1 [44,46]. Cytomorphologic equivalents show that the mutational subtype influences cell morphology - e.g., BRAF mutations being associated with epithelioid cells, and GNAQ/NF1 with spindle cells [44,46]. Interestingly, acral melanomas show increased mutational heterogeneity, with lower frequencies of BRAF mutations (34.4%) and increased frequencies of structural alterations and gene amplifications (CRKL, GAB2, PAK1, CCND1, TERT, MDM2) [47,48]. KIT mutations are particularly associated with amelanotic acral melanoma subtypes [44,46]. There is conflicting evidence on whether the number of acral nevi is a risk factor for acral melanoma [49]. In addition, it has been shown that while melanoma occurring on the dorsal hands and feet resemble other cutaneous melanoma in having high incidence of BRAFV600E mutations and approximately 25% incidence of precursor nevus, those occurring one the volar surface have low frequency of BRAF mutation and ~10% precursor nevus association [50]. This divergence might suggest a decreased risk for acral melanomas progression from acral nevi that occur on palms/soles.

Mucosal sites

The genetic drivers of mucosal nevi have only been explored in a limited fashion, but there is evidence of divergence between nevi and melanoma patterns. In oral mucosal nevi, the BRAFV600E mutation frequency is 42%, while the frequency in oral mucosal melanoma is only 6.42% [51]. Similarly, in the female genital tract, nevi were shown to be predominantly BRAFV600E-positive (100% in common nevi, 75% in atypical nevi), while melanomas had <10% BRAFV600E frequency [45,52].

Molecular studies of primary and metastatic melanoma are more numerous, and demonstrate a mutation spectrum including KIT mutations (16–26%), with lower frequencies of NRAS (15%) and BRAF (5–8%) mutations, and hardly any UVR-associated mutagenesis [53,54]. In addition, mucosal melanomas are most frequently found to have somatic structural alterations and chromosomal copy number changes rather than single-point mutations. A subset of mucosal melanomas (~9.5%) with GNAQ and GNAI mutations have worsened prognosis, thus also exhibiting evidence of molecular heterogeneity [55]. Overall, these findings argue that mucosal melanomas are less likely to evolve from benign precursor nevi.

Experimental Evidence for Anatomically Programmed Oncogenic Competence in Melanocytes

As discussed previously, oncogenic driver mutations in melanoma differ based on anatomic site. For example, while BRAF/NRAS mutations are predominant in cutaneous melanoma, they are less common in acral melanoma and mucosal melanomas. The mechanism behind these differential mutation patterns is unclear. It is possible that the processes driving mutations differ based on anatomic site. Chronic ultraviolet radiation is thought to drive cutaneous melanoma at cutaneous sites, as evidenced by high mutational burden and predominance of “UV signature” mutations in the lesions [56]. High mutational burden and UVB signature are found in conjunctival melanomas (UV-exposed mucosal melanoma variant), and subungual acral melanomas (that occur on dorsal, sun-exposed surfaces), consistent with the exposure of these sites to UV radiation [47,57]. Conversely, mutational burden is lower, and UVB signature largely absent, in mucosal and sun-protected acral melanoma.

Interestingly, BRAFV600E and the majority of NRAS driver mutations in melanoma are not UV-signature mutations, which opens the question as to how these might be related to UV exposure. While evidence suggests that UVB can at low frequency cause DNA mutations identical to those that cause BRAFV600E mutation, much evidence argues against a role of UVB in BRAFV600E mutation [58]. Cutaneous melanomas that lack BRAF or NRAS mutations are most commonly occur on chronic sun-damaged sites (that receive the highest cumulative UVB dosage) and exhibit a very high mutational burden and strong UV signature, while BRAFV600E mutant melanomas are less common on chronically sun-exposed sites and are associated with a lower mutational burden [59].

An alternative model is that melanocytes may have differential sensitivities to respond to different activating oncogenes. The first study to support this model demonstrated that after expression of BRAFV600E along with additional mutations, the ability to transform to melanoma depended on the intrinsic transcriptional program present in the cell of origin [60]. In a melanoma prone p53-/- genetic background, induction of BRAFV600E in melanoblast and neural crest lineage caused melanoma induction, while BRAFV600E did not cause melanoma when expressed in differentiated melanocytes. Enhanced expression of the chromatin modifier ATAD2 in melanoblast/neural crest lineages was linked to this differential response, suggesting that transcriptional program of the cell of origin, including chromatin modifiers such as ATAD2, regulate responses to oncogenic mutations.

Recent experimental work also suggests that melanocytes at different anatomic sites, despite a shared developmental origin, display distinct cell states that correlate with distinct oncogene response. This is a paradigm shift with profound implications: the same oncogene can initiate melanoma in one anatomical site and be biologically quiescent in another. Weiss et al., demonstrated that the CRKL gene is frequently amplified in human acral melanoma and that CRKL overexpression preferentially led to tumor development in the fins of zebrafish, the evolutionary equivalents of tetrapod limbs [61]. Tumorigenesis required the existence of HOX13-controlled positional identity (HOXA13, HOXB13, HOXD13), which controlled IGF signaling in conjunction with CRKL. Disruption of CRKL or HOX13 activity inhibited transformation in acral sites, emphasizing that oncogenic mutation can be transforming only in cells with the appropriate spatial transcriptional program. The relevance to humans is underscored by the enrichment of HOX13 expression and CRKL/GAB2 amplifications in human acral melanoma, in support of a conserved, site-specific susceptibility model [61].

A mucosal melanoma model was developed by Babu et al., where CCND1 overexpression in combination with PTEN and TP53 loss led to transformation solely in internal (mucosal-like) melanocytes, while cutaneous melanocytes harboring the identical mutations remained refractory [62]. Epigenomic and transcriptomic profiling revealed mucosal melanocytes possess an alternate chromatin structure, reduced antigen presentation, and elevated neural crest migration signatures. These elements were associated with PAX3 motif enrichment in open chromatin, suggesting that PAX3 confers a permissive transcriptional state for transformation. Overexpression of PAX3 increased the pool of internal melanocytes, supporting its role in mucosal melanocyte identity and oncogene competence [62].

|

Gene/Mutation |

Phenotype |

Anatomical Site |

Probable Oncogenic Drive |

Reference |

|

BRAFV600E |

Globular nevi; junctional/compound pattern; common acquired nevi |

Face, trunk (esp. young individuals) |

MAPK activation; limited proliferation → senescence; requires secondary hits for melanoma |

[25,27,30] |

|

NRAS Q61 |

Reticular nevi; lentiginous growth; dysplastic features |

Older individuals; various sites |

MAPK activation; more genomic instability; potential for progression |

[15,27] |

|

NRAS Q61 (GCMN) |

Giant congenital nevi; heterogeneous surface, asymmetric margins |

Whole body (PAS >60 cm) |

Early embryonic activation; high proliferation; increased melanoma risk |

[35,38,42] |

|

BRAFV600E (GCMN) |

Multinodular pattern; satellite lesions; pruritus |

Trunk, limbs |

High mitotic activity; deep tissue infiltration; strong BRAFV600E IHC expression |

[35–38, 41] |

|

BRAF fusions |

Proliferative congenital nevi; mucosal satellite lesions |

Skin, mucosa |

Strong proliferative drive; often itchy; rare variants (e.g., CUX1-BRAF) |

[36–38, 41] |

|

KIT mutations |

Amelanotic acral melanoma |

Palms, soles |

Low BRAF/NRAS frequency; structural variants; KIT-driven MAPK activation |

[44,48] |

|

GNAQ / NF1 |

Acral nevi with spindle cell morphology |

Palms, soles |

Non-MAPK proliferation signals; morphology-linked transformation |

[44,46] |

|

CRKL amplification |

Acral melanoma (non-nevus derived) |

Digits, nails, volar surfaces |

IGF signaling via CRKL; requires HOX13 positional identity for transformation |

[61] |

|

CCND1 + PTEN/TP53 loss |

Mucosal melanoma |

Oral/genital mucosa |

Transformation limited to mucosal melanocytes; PAX3-driven chromatin state |

[62] |

|

BRAFV600E (mucosa) |

Benign mucosal nevi (common) |

Oral, genital mucosa |

Frequent in nevi, rare in mucosal melanomas |

[45,51,52] |

|

GNAQ (mucosa) |

Subtype of mucosal melanoma (~9.5%) |

Mucosa |

Rare; molecularly distinct subset |

[55] |

Conclusions

Overall, recent evidence suggests that the interplay of genetic drivers and developmental and anatomic context impacts nevogenesis and melanoma pathogenesis. Identical oncogenic genetic alterations (e.g. BRAFV600E or NRAS codon 61 mutations, CRKL amplification, CCND1 mutation) are able to exert different biologic effects depending upon melanocyte positional dependent transcriptional programs, epigenetic terrain, and microenvironmental signals as key determinants of malignant competence.

Further delineating the transcriptional, epigenetic, and microenvironmental programs specifying melanocytic positional identity will be critical in understanding the events responsible for melanoma formation, and may also provide important clues for differential therapy responses of melanoma types. For example acral and mucosal melanoma demonstrate much lower response to immunotherapy [63]. While low therapy response is correlated to lower mutational burden in these tumors, it is possible that epigenomic or other aspects of positional cell state may impact therapy responses. Through the integration of mutational, transcriptional, and epigenomic landscape of melanocytes, improved understanding of melanocytes positional and developmental identity will improve our understanding of melanocyte and melanoma biology.

Author Contribution Statement

KK, SMO, and DEF contributed to literature review and writing/editing of the manuscript.

References

2. Schadendorf D, Fisher DE, Garbe C, Gershenwald JE, Grob JJ, Halpern A, et al. Melanoma. Nature reviews Disease primers. 2015 Apr 23;1(1):1-20.

3. Sommer L. Generation of melanocytes from neural crest cells. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011 Jun;24(3):411-21.

4. Brenner M, Hearing VJ. The protective role of melanin against UV damage in human skin. Photochem Photobiol. 2008 May-Jun;84(3):539-49.

5. Slominski A, Tobin DJ, Shibahara S, Wortsman J. Melanin pigmentation in mammalian skin and its hormonal regulation. Physiol Rev. 2004 Oct;84(4):1155-228.

6. Tang J, Fewings E, Chang D, Zeng H, Liu S, Jorapur A, et al. The genomic landscapes of individual melanocytes from human skin. Nature. 2020 Oct;586(7830):600-5.

7. Dankort D, Curley DP, Cartlidge RA, Nelson B, Karnezis AN, Damsky WE Jr, et al. Braf(V600E) cooperates with Pten loss to induce metastatic melanoma. Nat Genet. 2009 May;41(5):544-52.

8. Aggarwal P, Knabel P, Fleischer AB Jr. United States burden of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer from 1990 to 2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021 Aug;85(2):388-95.

9. Whiteman DC, Green AC, Olsen CM. The Growing Burden of Invasive Melanoma: Projections of Incidence Rates and Numbers of New Cases in Six Susceptible Populations through 2031. J Invest Dermatol. 2016 Jun;136(6):1161-71.

10. Pollock PM, Harper UL, Hansen KS, Yudt LM, Stark M, Robbins CM, et al. High frequency of BRAF mutations in nevi. Nat Genet. 2003 Jan;33(1):19-20.

11. Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, et al. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002 Jun 27;417(6892):949-54.

12. Shain AH, Yeh I, Kovalyshyn I, Sriharan A, Talevich E, Gagnon A, et al. The Genetic Evolution of Melanoma from Precursor Lesions. N Engl J Med. 2015 Nov 12;373(20):1926-36.

13. Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, Patel HN, Busam KJ, Kutzner H, Cho KH, Aiba S, Bröcker EB, LeBoit PE, Pinkel D, Bastian BC. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005 Nov 17;353(20):2135–47.

14. Bennett DC. Review: Are moles senescent? Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2024 May;37(3):391-402.

15. Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Soengas MS, Denoyelle C, Kuilman T, van der Horst CM, et al. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi. Nature. 2005 Aug 4;436(7051):720-4.

16. Patton EE, Widlund HR, Kutok JL, Kopani KR, Amatruda JF, Murphey RD, et al. BRAF mutations are sufficient to promote nevi formation and cooperate with p53 in the genesis of melanoma. Curr Biol. 2005 Feb 8;15(3):249-54.

17. Hodis E, Torlai Triglia E, Kwon JYH, Biancalani T, Zakka LR, Parkar S, et al. Stepwise-edited, human melanoma models reveal mutations' effect on tumor and microenvironment. Science. 2022 Apr 29;376(6592):eabi8175.

18. Shain AH, Bastian BC. From melanocytes to melanomas. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016 Jun;16(6):345-58.

19. Tsao H, Bevona C, Goggins W, Quinn T. The transformation rate of moles (melanocytic nevi) into cutaneous melanoma: a population-based estimate. Arch Dermatol. 2003 Mar;139(3):282-8.

20. Shain AH, Joseph NM, Yu R, Benhamida J, Liu S, Prow T, et al. Genomic and Transcriptomic Analysis Reveals Incremental Disruption of Key Signaling Pathways during Melanoma Evolution. Cancer Cell. 2018 Jul 9;34(1):45-55.e4.

21. de la Fouchardière A, Pissaloux D, Houlier A, Paindavoine S, Tirode F, LeBoit PE, et al. Histologic and Genetic Features of 51 Melanocytic Neoplasms With Protein Kinase C Fusion Genes. Mod Pathol. 2023 Nov;36(11):100286

22. Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, Bauer J, Gaugler L, O'Brien JM, et al. Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue naevi. Nature. 2009 Jan 29;457(7229):599-602.

23. Wiesner T, He J, Yelensky R, Esteve-Puig R, Botton T, Yeh I, et al. Kinase fusions are frequent in Spitz tumours and spitzoid melanomas. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3116.

24. Newman S, Fan L, Pribnow A, Silkov A, Rice SV, Lee S, et al. Clinical genome sequencing uncovers potentially targetable truncations and fusions of MAP3K8 in spitzoid and other melanomas. Nat Med. 2019 Apr;25(4):597-602.

25. Karram S, Novy M, Saroufim M, Loya A, Taraif S, Houreih MA, et al. Predictors of BRAF mutation in melanocytic nevi: analysis across regions with different UV radiation exposure. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013 Jun;35(4):412-8.

26. Maher NG, Scolyer RA, Colebatch AJ. Biology and genetics of acquired and congenital melanocytic naevi. Pathology. 2023 Mar;55(2):169-77.

27. Marchetti MA, Kiuru MH, Busam KJ, Marghoob AA, Scope A, Dusza SW, et al. Melanocytic naevi with globular and reticular dermoscopic patterns display distinct BRAF V600E expression profiles and histopathological patterns. Br J Dermatol. 2014 Nov;171(5):1060-5.

28. Roh MR, Eliades P, Gupta S, Tsao H. Genetics of melanocytic nevi. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2015 Nov;28(6):661-72.

29. Kiuru M, Tartar DM, Qi L, Chen D, Yu L, Konia T, et al. Improving classification of melanocytic nevi: Association of BRAF V600E expression with distinct histomorphologic features. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018 Aug;79(2):221-9.

30. Tan JM, Tom LN, Jagirdar K, Lambie D, Schaider H, Sturm RA, et al. The BRAF and NRAS mutation prevalence in dermoscopic subtypes of acquired naevi reveals constitutive mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway activation. Br J Dermatol. 2018 Jan;178(1):191-7.

31. Stark MS, Tan JM, Tom L, Jagirdar K, Lambie D, Schaider H, et al. Whole-Exome Sequencing of Acquired Nevi Identifies Mechanisms for Development and Maintenance of Benign Neoplasms. J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Jul;138(7):1636-44.

32. Muse ME, Bergman DT, Salas LA, Tom LN, Tan JM, Laino A, et al. Genome-Scale DNA Methylation Analysis Identifies Repeat Element Alterations that Modulate the Genomic Stability of Melanocytic Nevi. J Invest Dermatol. 2022 Jul;142(7):1893-902.e7.

33. Kinsler VA, O'Hare P, Bulstrode N, Calonje JE, Chong WK, Hargrave D, et al. Melanoma in congenital melanocytic naevi. Br J Dermatol. 2017 May;176(5):1131-43.

34. Charbel C, Fontaine RH, Malouf GG, Picard A, Kadlub N, El-Murr N, et al. NRAS mutation is the sole recurrent somatic mutation in large congenital melanocytic nevi. J Invest Dermatol. 2014 Apr;134(4):1067-74.

35. Polubothu S, McGuire N, Al-Olabi L, Baird W, Bulstrode N, Chalker J, et al. Does the gene matter? Genotype-phenotype and genotype-outcome associations in congenital melanocytic naevi. Br J Dermatol. 2020 Feb;182(2):434-43.

36. Krengel S, Scope A, Dusza SW, Vonthein R, Marghoob AA. New recommendations for the categorization of cutaneous features of congenital melanocytic nevi. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013 Mar;68(3):441-51.

37. Martins da Silva V, Martinez-Barrios E, Tell-Martí G, Dabad M, Carrera C, Aguilera P, et al. Genetic Abnormalities in Large to Giant Congenital Nevi: Beyond NRAS Mutations. J Invest Dermatol. 2019 Apr;139(4):900–8.

38. Molho-Pessach V, Hartshtark S, Merims S, Lotem M, Caplan N, Alfassi H, et al. Giant congenital melanocytic naevus with a novel CUX1-BRAF fusion mutation treated with trametinib. Br J Dermatol. 2022 Dec;187(6):1052-54.

39. Nagarkar A, Turbeville J, Hinshaw MA, LeBoit PE, Gagan J, Raffeld M, et al. Large Congenital Melanocytic Nevus With LMNA::NTRK1 Fusion: Expanding Targeted Therapy Options for Congenital Nevi and Melanoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2025 Aug;52(8):523-7.

40. Perkins IU, Tan SY, McCalmont TH, Chou PM, Mully TW, Gerami P, et al. Melanoma in infants, caused by a gene fusion involving the anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2024 Jan;37(1):6-14.

41. Roy SF, Agim NG, Mir A, Couts KL, Vandergriff T, Robinson WA, et al. Congenital melanocytic nevi initiated by BRAF fusion oncogene with firmness, pruritus, and desmoplastic stroma. Br J Dermatol. 2025 Feb 27:ljaf061.

42. Zhao X, Dai Y, Zhang L, Liu Y, Chen H, Yue X, et al. NRAS p.Q61R/K allele load is correlated to different phenotypes of congenital melanocytic naevi. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022 Dec;47(12):2201-07.

43. Francis JH, Grossniklaus HE, Habib LA, Marr B, Abramson DH, Busam KJ. BRAF, NRAS, and GNAQ Mutations in Conjunctival Melanocytic Nevi. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2018 Jan 1;59(1):117-21.

44. Moon KR, Choi YD, Kim JM, Jin S, Shin MH, Shim HJ, et al. Genetic Alterations in Primary Acral Melanoma and Acral Melanocytic Nevus in Korea: Common Mutated Genes Show Distinct Cytomorphological Features. J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Apr;138(4):933-45.

45. Tseng D, Kim J, Warrick A, Nelson D, Pukay M, Beadling C, et al. Oncogenic mutations in melanomas and benign melanocytic nevi of the female genital tract. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Aug;71(2):229-36.

46. Smalley KSM, Teer JK, Chen YA, Wu JY, Yao J, Koomen JM, et al. A Mutational Survey of Acral Nevi. JAMA Dermatol. 2021 Jul 1;157(7):831-5.

47. Newell F, Wilmott JS, Johansson PA, Nones K, Addala V, Mukhopadhyay P, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of acral melanoma reveals genomic complexity and diversity. Nat Commun. 2020 Oct 16;11(1):5259.

48. Yeh I, Jorgenson E, Shen L, Xu M, North JP, Shain AH, et al. Targeted Genomic Profiling of Acral Melanoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019 Oct 1;111(10):1068-77.

49. Park S, Yun SJ. Acral Melanocytic Neoplasms: A Comprehensive Review of Acral Nevus and Acral Melanoma in Asian Perspective. Dermatopathology (Basel). 2022 Aug 19;9(3):292-303.

50. Haugh AM, Zhang B, Quan VL, Garfield EM, Bubley JA, Kudalkar E, et al. Distinct Patterns of Acral Melanoma Based on Site and Relative Sun Exposure. J Invest Dermatol. 2018 Feb;138(2):384-93.

51. Resende TAC, de Andrade BAB, Bernardes VF, Coura BP, Delgado-Azãnero W, Mosqueda-Taylor A, et al. BRAFV600E mutation in oral melanocytic nevus and oral mucosal melanoma. Oral Oncol. 2021 Mar;114:105053.

52. Yélamos O, Merkel EA, Sholl LM, Zhang B, Amin SM, Lee CY, et al. Nonoverlapping Clinical and Mutational Patterns in Melanomas from the Female Genital Tract and Atypical Genital Nevi. J Invest Dermatol. 2016 Sep;136(9):1858–65.

53. Abu-Abed S, Pennell N, Petrella T, Wright F, Seth A, Hanna W. KIT gene mutations and patterns of protein expression in mucosal and acral melanoma. J Cutan Med Surg. 2012 Mar-Apr;16(2):135-42.

54. Satzger I, Schaefer T, Kuettler U, Broecker V, Voelker B, Ostertag H, et al. Analysis of c-KIT expression and KIT gene mutation in human mucosal melanomas. Br J Cancer. 2008 Dec 16;99(12):2065-9.

55. Sheng X, Kong Y, Li Y, Zhang Q, Si L, Cui C, et al. GNAQ and GNA11 mutations occur in 9.5% of mucosal melanoma and are associated with poor prognosis. Eur J Cancer. 2016 Sep;65:156-63.

56. Thomsen K, Eriksen EF, Jørgensen JC, Charles P, Mosekilde L. Seasonal variation of serum bone GLA protein. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1989 Nov;49(7):605–11.

57. Mundra PA, Dhomen N, Rodrigues M, Mikkelsen LH, Cassoux N, Brooks K, et al. Ultraviolet radiation drives mutations in a subset of mucosal melanomas. Nat Commun. 2021 Jan 11;12(1):259.

58. Laughery MF, Brown AJ, Bohm KA, Sivapragasam S, Morris HS, Tchmola M, et al. Atypical UV Photoproducts Induce Non-canonical Mutation Classes Associated with Driver Mutations in Melanoma. Cell Rep. 2020 Nov 17;33(7):108401.

59. Mar VJ, Wong SQ, Li J, Scolyer RA, McLean C, Papenfuss AT, et al. BRAF/NRAS wild-type melanomas have a high mutation load correlating with histologic and molecular signatures of UV damage. Clin Cancer Res. 2013 Sep 1;19(17):4589-98.

60. Baggiolini A, Callahan SJ, Montal E, Weiss JM, Trieu T, Tagore MM, et al. Developmental chromatin programs determine oncogenic competence in melanoma. Science. 2021 Sep 3;373(6559):eabc1048.

61. Weiss JM, Hunter MV, Cruz NM, Baggiolini A, Tagore M, Ma Y, et al. Anatomic position determines oncogenic specificity in melanoma. Nature. 2022 Apr;604(7905):354-61.

62. Babu S, Chen J, Robitschek E, Baron CS, McConnell A, Wu C, et al. Specific oncogene activation of the cell of origin in mucosal melanoma. bioRxiv [Preprint]. 2024 Apr 26:2024.04.22.590595.

63. Klemen ND, Wang M, Rubinstein JC, Olino K, Clune J, Ariyan S, et al. Survival after checkpoint inhibitors for metastatic acral, mucosal and uveal melanoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2020 Mar;8(1):e000341.