Abstract

Introduction: Pain significantly impacts quality of life, yet healthcare providers in resource-limited settings such as Ghana often struggle to detect and manage pain sufficiently. This study examines pain prevalence and management strategies across different age groups in a Ghanaian teaching hospital.

Method: A cross-sectional, mixed-methods study was carried out at Cape Coast Teaching Hospital (CCTH). The study considered categories of participants: infants, children and adults. Data were collected using structured questionnaires. The FLACC scale rated infant pain, the Wong-Baker FACES measured child pain, and the McGill Pain Questionnaire assessed adult pain.

Results: Distinct patterns of pain experience across different age groups were observed. Among infants, 70.9% experienced pain, with malaria (16.7%), car accidents (14.1%) and jaundice (11.5%) as the main causes. Infants experienced acute pain the most, affecting 80%. Among children, abdominal pain (61.6%) was the leading form of pain among those who experienced pain (58.6%). For adults, 60% reported experiencing pain mainly due to ongoing medical problems (28.7%). Adults experienced more chronic pain episodes (56.0%). Across all age groups, pharmacotherapy was the primary treatment approach, with paracetamol and ibuprofen being the most prescribed pain relievers. Treatment outcomes varied, with 25.0% experiencing complete relief, 29.0% partial relief and 45.9% reporting no relief.

Conclusion: The research data illustrate widespread pain among all age categories, thus demanding specialized assessment instruments and tailored management solutions for various patient age groups. Pain relief was mostly pharmacological, but many chronic pain patients reported only temporary relief. The study emphasizes the need for pain clinics with suitable age-appropriate management strategies, advocating patient-centered care to improve treatment outcomes and quality of life.

Keywords

Pain prevalence, Pain management, FLACC scale, Wong-Baker FACES, McGill Pain Questionnaire

Introduction

Pain represents a significant global health issue with serious consequences for both individual well-being and societal functioning. The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) characterizes pain as an "unpleasant sensory and emotional experience linked to actual or potential tissue damage" [1]. It is estimated that worldwide, 1 in 5 people experience pain, with approximately 1 in 10 adults receiving a diagnosis of chronic pain annually [2]. Pain affects individuals across all demographics, including age, gender, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and geographic location; however, its prevalence is not evenly distributed. This uneven distribution underscores the disparities in access to healthcare and the effectiveness of treatment [3]. Hall and Anand emphasize that if pain experienced in early childhood is not properly managed, it can result in lasting physiological and psychological effects [4].

Chronic pain in children that is inadequately treated can result in persistent pain in adulthood [5]. Individuals experiencing pain may encounter it in various forms, including acute, chronic, intermittent, or a combination thereof [6]. Despite the widespread impact of pain across all age groups, from infants to adults, pain management often lacks adequate focus, especially in healthcare settings with limited resources, such as those in Ghana. The ongoing issue of under-treatment of pain is a significant concern. To effectively address this challenge, there is a need for enhanced diagnostic and treatment approaches grounded in a public health framework [7]. In the United States, the societal costs associated with the care of children and adolescents suffering from moderate to severe chronic pain have been estimated to reach $19.5 billion annually [8].

Pain is a subjective experience that, despite being widely acknowledged, remains challenging to articulate [9]. In infants, pain typically arises as a direct reaction to negative stimuli such as tissue injury, illness, or surgical procedures [10]. Nonetheless, intense pain can manifest without any clear underlying cause, as observed in certain neuropathic pain disorders, diabetic neuropathy, or it may persist long after the initial injury has healed, as is the case with post-surgical pain [11]. Neuropathic pain, which does not correlate with current tissue damage, significantly contributes to suffering and functional limitations in pediatric populations, including newborns. This type of pain often shows inadequate response to conventional analgesic treatments, complicating its management [12].

Research indicates that pediatric pain differs significantly from adult pain due to children's unique cognitive, emotional, and communicative challenges. This highlights the need for an age-specific approach to pain assessment and management [13]. It is well-documented that over 10% of hospitalized children experience chronic pain symptoms, yet this condition often goes underdiagnosed and inadequately treated [14]. Activating SIRT1 has been shown to provide relief for pain conditions in different age groups [15]. Effective pain management relies on thorough pain evaluation; children who do not receive proper pain assessments are frequently undertreated, and their pain is often underestimated. This issue is particularly pronounced in patients with mental health issues or those who are non-verbal. While there are age-appropriate, standardized, and reliable evaluation tools available, these alone are not sufficient. To ensure comprehensive pain management, it is essential to also assess the child's quality of life, including factors such as sleep, social interactions, and academic performance [16]. For older children capable of articulating their pain experiences, self-reporting pain assessments are considered the gold standard [17].

An effective strategy for pain management necessitates a comprehensive approach that incorporates both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. These methods are designed to alleviate pain perception, enhance functionality, and improve overall quality of life [18]. Chronic pain represents a considerable challenge for both patients and their families, often leading to a decline in perceived health, disruption of daily activities, increased risk of depression, and adverse effects on personal relationships and social interactions [19]. Research investigating the prevalence of pain in Ghana and other sub-Saharan African nations has been relatively limited. In this region, the challenges of inadequate pain management are exacerbated by insufficient funding, a lack of trained professionals, and a dearth of effective pain assessment tools [20].

Understanding the prevalence and pain management strategies is crucial in providing effective healthcare interventions and improving patient outcomes. Hence, this study sought to assess the prevalence of pain management approaches among patients at different stages of life in CCTH, Ghana.

Method

Study design and setting

The study employed descriptive, cross-sectional, and mixed methods designs to provide a comprehensive understanding of pain experiences among infants, children, adolescents, and adults. Quantitative data were collected through structured questionnaires. This study was carried out at the Cape Coast Teaching Hospital (CCTH), a key referral and teaching facility serving the Central and Western regions of Ghana. With its range of specialized clinics, including Pediatrics, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), Oncology, Neurology, Diabetic, and Orthopedic units, CCTH provided an ideal setting for investigating pain prevalence and management.

Population, sampling and sample size

All participants were patients of the Cape Coast Teaching Hospital. A stratified sampling technique was used in recruiting participants. There were three distinct groups within the population: infants (2 months to 3 years), children (4 to 16 years) and adults (17 years and older) (ECCD Standards, 2018). A convenient sampling approach was further used in selecting participants within the three distinct age groups. A sample size of 385 participants was computed using Cochran’s Sample Size Formula for an infinite population since the population size was unknown: n0=[z2⋅p⋅(1−p)]/e2.

e: desired level of precision, the margin of error (0.05); p: the fraction of the population (as a percentage) that displays the attribute (50%); z: the z-value, extracted from a z-table (1.96). A sample size of 250 adults, 110 children, and 99 infants was finally used in the research, making room for no responses, attrition and incomplete responses.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study included only adult participants who provided written informed consent or minors enrolled with the consent of their accompanying guardians. Adult participants were only recruited if they were not suffering from any mental condition, and were attending the Oncology, Diabetic, Orthopedic, or Neurology clinics from January–December 2024. Patients who were critically ill and individuals with cognitive impairments that hindered reliable self-reporting were excluded.

Data collection

Data collection tools: The Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability (FLACC) scale was used to assess pain among the infants. This scale was particularly suitable for non-verbal participants as infants, since they cannot articulate their feelings well verbally.

For children, the Wong-Baker FACES scale was employed. It was used to gauge pain intensity through visual representations, which are effective for children. The Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale has been rigorously validated and has shown good psychometric properties, making it a reliable and valid instrument for assessing pain intensity in pediatric populations. Its simplicity, visual appeal, and consistent validity across studies have contributed to its widespread use in clinical and research settings for pain assessment in children [21].

The McGill questionnaire was used to obtain data from adults. Data was collected on mobile devices through Google Forms. Structured questionnaires, interviews, and standardized pain assessment tools were utilized to capture the severity, location, duration, pain management and impact of pain on quality of life. The structured questionnaires utilized validated scales such as the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) for pain intensity and the Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) for pain impact.

Data collection procedure: Data collection was conducted through a combination of interviews, clinical observations, and reviews of patient records. Participants were recruited during routine clinic visits. Written informed consent was obtained from adult participants and parents or guardians of minors. Infants’ pain behaviors were observed and recorded during routine pediatric check-ups. Children were asked to self-report pain using the Wong-Baker FACES scale, supplemented by input from their caregivers where necessary. Adult participants detailed their pain experiences through interviews, emphasizing their impact on daily activities, psychological well-being, and social functioning.

Data on pain's location, duration, and severity were captured alongside treatment regimens and outcomes. All data collection instruments were pre-tested in a pilot study among 10 adults and 5 children at the University of Cape Coast Hospital to refine questions and procedures and maintain the validity of the research instruments. All interviews were conducted face-to-face.

Data analysis

Quantitative data from the questionnaires were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics. Statistical Package for Social Scientists (SPSS) Version 24.0 was used to analyze the data. The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants were described using frequencies, percentages, means, standard deviation, and range statistics. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize demographic characteristics, pain prevalence, and management practices. Inferential statistics, including chi-square tests and logistic regression, were used to identify factors associated with pain severity and management satisfaction.

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee of the Cape Coast Teaching Hospital. The approval number is CCTHERC/EC/2023/182. Informed consent was obtained from all participants or caregivers. Confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the research process.

Results

A total of 459 individuals participated in this study. The study population comprised infants aged 2 months to 3 years, children aged 4 to 16 years, and adults aged 17 years and above. Among infants, there was an equal distribution of 55 males and 55 females (50% each). In children aged 4 to 16 years, the gender distribution was approximately 58(58.59%) male and 41(41.41%) female. Among adults, women 134 (53.60%) outnumbered men 116 (46.40%), as shown in Table 1.

|

Variable |

Frequency (%) |

||

|

|

Infants (2 months - 3 years) N=110 |

Children (4- 16 years) N=99 |

Adults (17 years and older) N=250 |

|

Gender |

|||

|

Female |

55 (50.00) |

58 (58.59) |

134 (53.60) |

|

Male |

55 (50.00) |

41 (41.41) |

116 (46.40) |

|

Age |

|||

|

1-3 years |

61 (55.45) |

|

|

|

2 - 5 months |

23 (20.91) |

|

|

|

6 months -11 months |

26 (23.64) |

|

|

|

4-8 |

|

42 (42.42) |

|

|

9-12 |

|

38 (38.38) |

|

|

13-15 |

|

19 (19.19) |

|

|

16 - 24 |

|

|

18 (7.20) |

|

25 - 34 |

|

|

40 (16.00) |

|

35 - 44 |

|

|

56 (22.40) |

|

45 - 54 |

|

|

62 (24.80) |

|

55 - 64 |

|

|

31 (12.40) |

|

≥ 65 |

|

|

43 (17.20) |

|

Pain |

|||

|

No |

32 (29.09) |

58 (58.59) |

150 (60.00) |

|

Yes |

78 (70.91) |

41 (41.41) |

100 (40.00) |

|

Mode of feeding |

|||

|

Breastfeeding |

48 (43.64) |

|

|

|

Meals |

61 (55.45) |

|

|

|

Both |

1 (0.91) |

|

|

|

Education |

|||

|

Up to Primary |

|

81 (81.82) |

|

|

Junior High School (JHS) |

|

18 (18.18) |

46 (18.40) |

|

Senior High School (SHS) |

|

|

63 (25.20) |

|

Tertiary |

|

|

82 (32.80) |

|

None |

|

|

59 (23.60) |

|

Religion |

|||

|

Christianity ` |

|

|

111 (44.40) |

|

Islam |

|

|

73 (29.30) |

|

Traditional |

|

|

19 (7.60) |

|

Other |

|

|

47 (18.80) |

|

Income |

|||

|

100 to 500 cedis |

|

|

80 (32.00) |

|

500 to 1000 cedis |

|

|

65 (26.00) |

|

Less than 100 cedis |

|

|

66 (26.00) |

|

More than 1000 cedis |

|

|

39 (15.60) |

|

Occupation |

|||

|

Health worker |

|

|

22 (8.80) |

|

Non-health worker |

|

|

142 (56.80) |

|

Student |

|

|

34 (13.60) |

|

Unemployed |

|

|

52 (20.80) |

|

Duration of Pain |

|||

|

Less than 1 month |

|

93 (93.94) |

|

|

More than 1 year |

|

6 (6.0) |

|

|

1 to 3 months |

|

|

33 (22.00) |

|

3 to 6 months |

|

|

28 (18.67) |

|

6 to 12 months |

|

|

19 (12.67) |

|

Less than 1 month |

|

|

31 (20.67) |

|

More than 1 year |

|

|

39 (26.00) |

|

Frequency of Pain |

|||

|

Daily |

|

77 (77.78) |

22 (14.67) |

|

Weekly |

|

1 (1.01) |

43 (28.67) |

|

Monthly |

|

2 (2.02) |

18 (12.00) |

|

Occasionally |

|

19 (19.19) |

67 (44.67) |

|

Location of Pain |

|||

|

Abdomen |

|

61 (61.62) |

|

|

Wrist |

|

1 (1.01) |

|

|

Chest |

|

13 (13.13) |

|

|

Foot |

|

6 (6.06) |

|

|

Head |

|

7 (7.07) |

|

|

Leg |

|

8 (8.08) |

|

Table 2 shows the association between age, gender, and mode of feeding for infants with pain. Although differences were observed across the categories, none of the associations were statistically significant.

|

Variable |

No |

Yes |

X2 |

p-value |

|

Age |

||||

|

1-3 years |

13 |

48 |

4.02 |

0.13 |

|

2-6 months |

9 |

14 |

|

|

|

6 months - 1 year |

10 |

16 |

|

|

|

Gender |

||||

|

Female |

16 |

39 |

0.00 |

1.00 |

|

Male |

16 |

39 |

|

|

|

Mode of feeding |

||||

|

Breastfeeding |

16 |

32 |

1.07 |

0.58 |

|

Meals |

16 |

45 |

|

|

|

Both |

0 |

1 |

|

|

The majority of pain cases for infants were classified as acute (80.77%). Regarding pain mechanism, most infants experienced nociceptive pain (73.08%). Also, pain lasted for less than a month for the majority (84.62%) of children. The largest proportion of children experienced moderate pain improvement (35.9%), while 32.05% reported either high or low improvement (Table 3).

|

Parameter |

Frequency (%), n=78 |

|

Type |

|

|

Acute |

63 (80.77) |

|

Chronic |

4 (5.13) |

|

Subacute |

11 (14.10) |

|

By mechanism |

|

|

Neuropathic |

21 (26.920 |

|

Nociceptive |

57 (73.08) |

|

Duration |

|

|

1 to 3 months |

9 (11.54) |

|

More than 3 months |

3 (3.85) |

|

less than a month |

66 (84.62) |

|

Level of improvement |

|

|

High |

25 (32.05) |

|

Moderate |

28 (35.90) |

|

Little |

25 (32.05) |

Primary diagnosis and choice of pain management medication

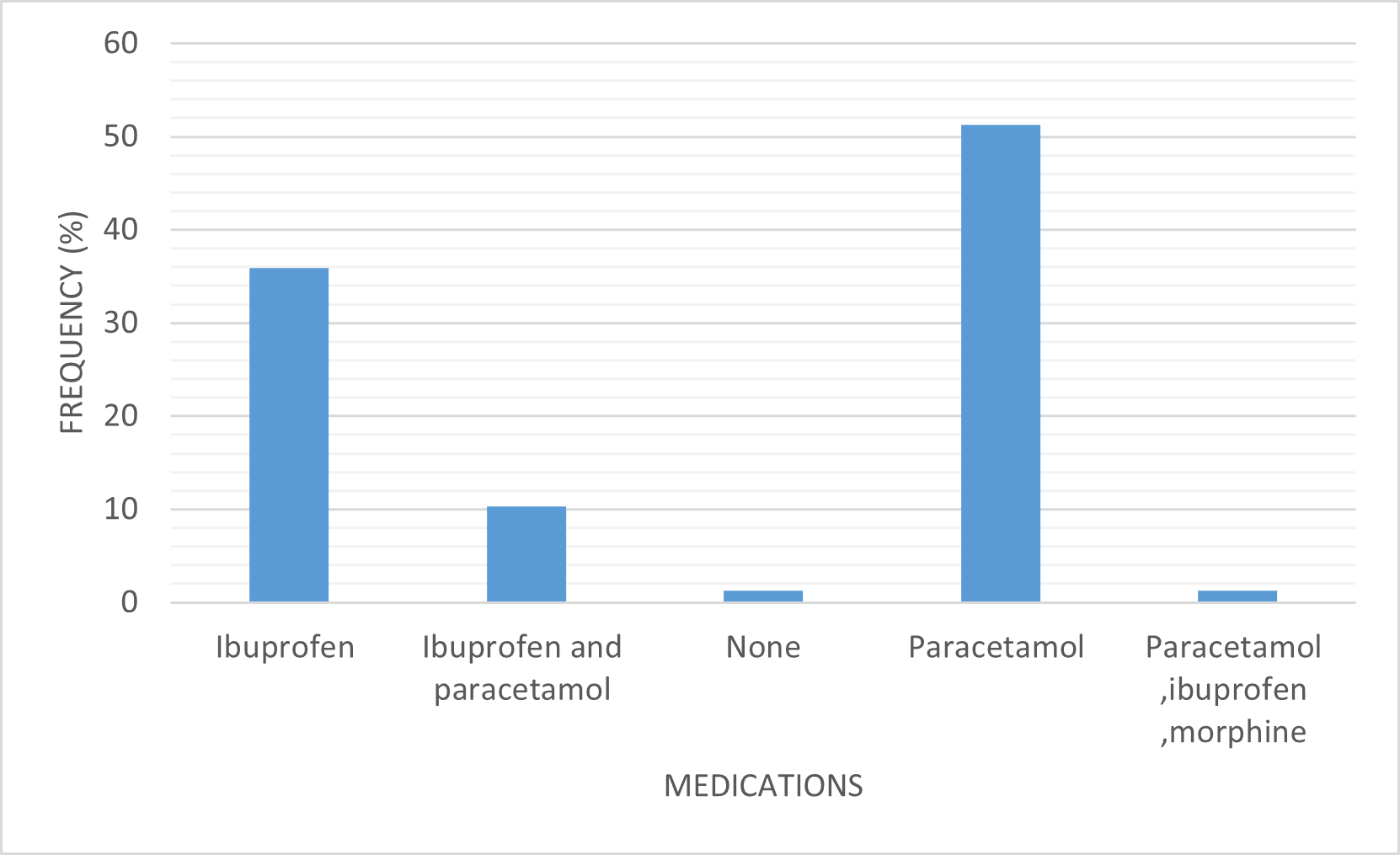

Among the infants, the commonest diagnosis was Malaria (18.1%), Fever (11.5%), Jaundice (5.1%), and upper respiratory tract infections (3.8%) were also among the common diagnosis. The most prescribed pain medication was paracetamol (47.4%) (Figure 1). Paracetamol is accessible and considered safe in infants when it is not contraindicated in diseases such as jaundice.

Figure 1. Choice of medication for pain management (2 months – 3 years).

|

Demographic |

Yes |

No |

P-value |

|

Gender |

|||

|

Female |

24 |

17 |

0.993 |

|

Male |

34 |

24 |

|

|

Age |

|||

|

4-8 |

22 |

20 |

|

|

9-12 |

19 |

19 |

|

|

13-16 |

17 |

2 |

0.010 |

|

Education |

|||

|

Junior High School |

15 |

3 |

|

|

Primary |

43 |

38 |

0.018 |

It was seen from the results obtained for children (4–16 years) that there was no statistically significant relationship between gender and pain. However, there was a statistically significant relationship between age and pain and with the level of education.

Although the relationship between pain and gender is insignificant, the odds of males experiencing pain were 0.85 times those of females. The odds of children aged 4-8 experiencing pain were 0.39 times those of 13-16-year-olds. The odds of children aged 9-12 experiencing pain were 0.68 times those of 13-16-year-olds (Table 5).

|

Pain odds |

Odds ratio |

Std Err |

P |

|

Male |

0.853 |

0.367 |

0.713 |

|

4-8 |

0.394 |

0.239 |

0.126 |

|

9-12 |

0.687 |

0.411 |

0.531 |

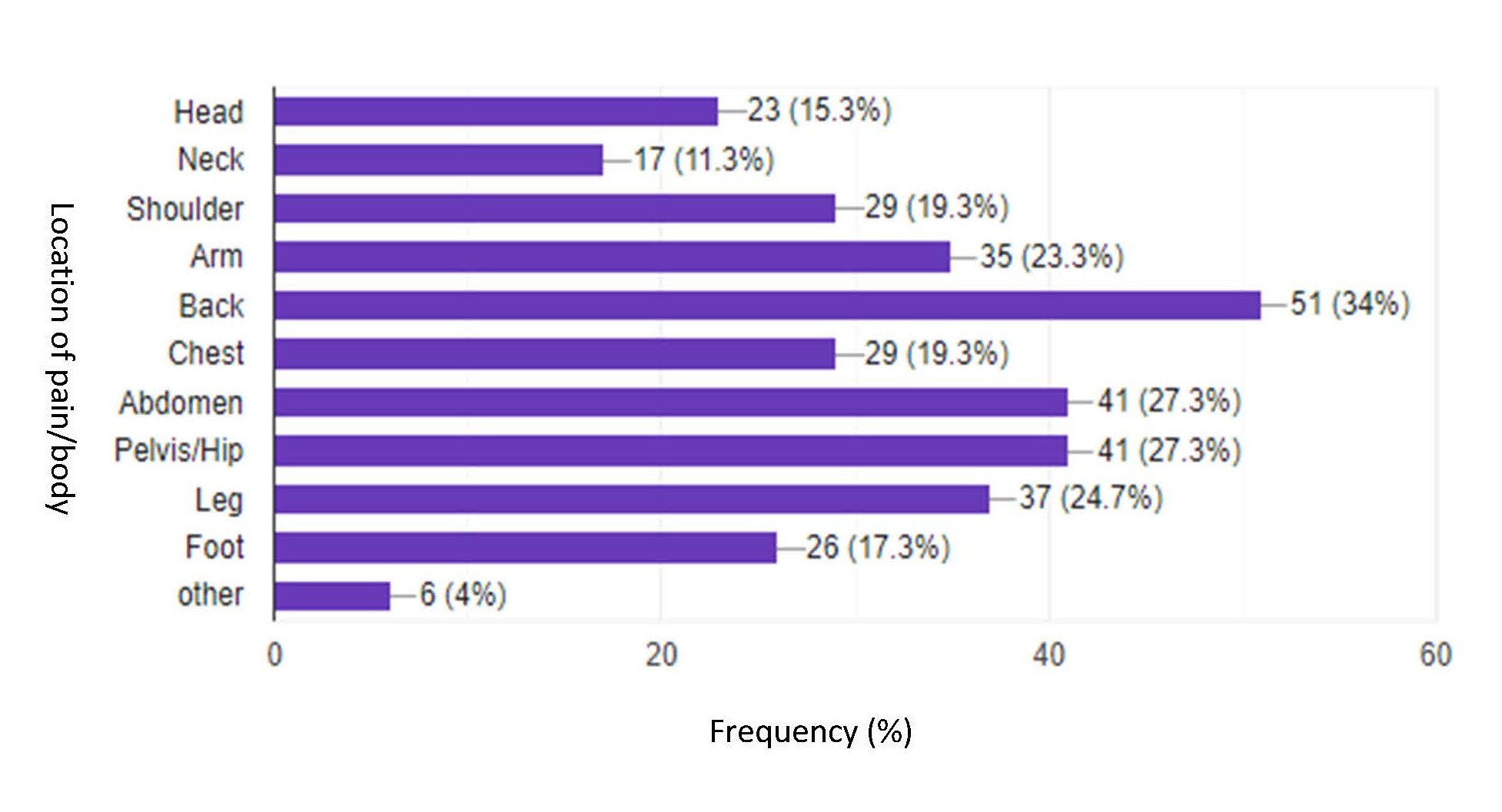

Out of the 250 adult participants interviewed, 150 (60.00%) had experienced pain. Participants from the OPD were 114, representing 46.1% of the studied population, while the in-patient participants were obtained from wards such as the female medical ward, female surgical ward, male medical ward, male surgical ward, and obstetrics and gynaecology. The in-patient participants were 136, making up 53.9% of the studied population. Average pain severity within the population according to the McGill questionnaire interpretation =38.26415. According to McGill, the least score =0. Maximum score =78. Hence population demonstrates moderate pain. The location of pain and gender distribution are shown in Figure 2 and Table 6, respectively.

Figure 2. Location of pain (17 years and above).

|

Gender |

Frequency, n=250 (%) |

Total |

|

|

No pain |

Pain |

||

|

Female |

43 (32.1) |

91 (67.9) |

134 (53.6%) |

|

Male |

57 (49.1) |

59 (50.9) |

116 (46.4%) |

|

Total prevalence |

60.0% |

||

|

Female prevalence |

36.4% |

||

|

Male prevalence |

23.6% |

||

Among adults studied, the majority of both females (67.9%) and males (50.9%) experienced pain. More females experienced pain as compared to their male counterparts. The pain prevalence was 36.4% and 23.6% for females and males, respectively, with a total prevalence of 60.0% (Table 6).

The most common cause of pain for adults was specific underlying medical conditions (28.67%), with the least common cause being labor (3.33%). Table 7 provides a summary of the causes of pain.

|

Cause of Pain |

Frequency (%), n=150 |

|

Medical conditions (E.g. Arthritis, Angina, etc.) |

43 (28.67) |

|

General surgery |

21 (14.00) |

|

Other |

19 (12.67) |

|

Infection |

18 (12.00) |

|

Injury/accident |

16 (10.67) |

|

Emotional or psychological (Stress, etc.) |

13 (8.67) |

|

Caesarian operation |

6 (4.00) |

|

Labor/birth |

5 (3.33) |

The output from the binary logistic regression, as presented in Table 8 below, revealed that there exists a significant positive relationship between the gender of the patient and the pain of the patient. With male as a reference category, the odds of a patient experiencing chronic pain are increased by 2.045 times if the patient is a female. It was further observed that there is a significant positive relationship between the patient's age and the patient's pain. This indicated that the odds of a patient experiencing chronic pain with an increase in age is 1.126.

|

Associations |

P – value |

Interpretation |

Cramer’s V |

Odds ratio |

|

Gender vs pain |

0.006 |

Significant Null hypothesis rejected |

0.1735 |

2.045 |

|

Age vs pain |

0.000 |

Significant Null hypothesis rejected |

0.3113 |

1.126 |

|

Religion vs pain |

0.649 |

|

|

|

|

Education vs pain |

0.104 |

Null hypothesis holds |

|

|

|

Marital status vs pain |

0.120 |

Null hypothesis holds |

|

|

|

Income vs pain |

0.468 |

Null hypothesis holds |

|

|

|

Occupation vs pain |

0.143 |

Null hypothesis holds |

|

|

|

Variables |

Frequency, n=148 |

Percentage (%) |

|

Type of Therapy |

||

|

Medication |

86 |

58.11 |

|

Physical therapy |

23 |

15.54 |

|

Surgery |

28 |

18.92 |

|

Other |

11 |

7.43 |

|

Type of Medicine |

||

|

Over the counter |

48 |

32.43 |

|

Prescription |

90 |

60.81 |

|

Other |

10 |

6.75 |

|

Duration of Medicine |

||

|

less than a month |

47 |

32.64 |

|

1-3 months |

50 |

34.72 |

|

3-6 months |

23 |

15.97 |

|

6-12 months |

16 |

11.11 |

|

1 year and above |

8 |

5.56 |

|

Treatment outcome (Relief) |

||

|

No |

68 |

45.95 |

|

Yes, completely |

37 |

25.00 |

|

Yes, partially |

43 |

29.00 |

Table 9 summarizes the distribution of therapy types, medicines used, treatment duration and outcomes among participants. The most common form of therapy was medication (58.11%). Among those using medications, 60.81% relied on prescription medicines while 32.43% used over-the-counter medications. The duration of medication use varied, with the largest proportion (34.72%) using medication for 1-3 months. Regarding treatment outcomes, 45.95% reported no relief, with 25% experiencing complete relief.

It was also found that there was no multidisciplinary unit in the hospital for pain management.

Discussion

Pain is a universal human experience that can significantly impact an individual's quality of life and overall well-being. It is a complex phenomenon influenced by various factors such as physical, psychological, and social elements. It is more difficult to evaluate and effectively treat pain in pediatric patients than in children and adult patients, and this symptom is frequently ignored or undertreated. Pain prevalence was found to be high among all stages. This high prevalence suggests that pain is a common issue and needs attention. Several causes of pain were identified among patients across the various stages of life in this study.

In infants, pain prevalence was high. This emphasizes the vulnerability of infants to pain due to their developing nervous systems and limited ability to express discomfort, which is consistent with a Canadian pediatric study [22]. The study also examined the association between the mode of feeding and the prevalence of pain among infants, there was no statistically significant association between them. This suggests that the mode of feeding does not have a noteworthy impact on the prevalence of pain among infants and aligns with previous research that found inconsistent links between feeding practices and pain perception in infants [23]. Malaria was the most common cause of pain among infants, followed by car accidents and jaundice. Given the high burden of malaria in this age group, preventive interventions are essential, especially considering the severity of its complications [24]. Most infants experienced pain that lasted less than one month, suggesting pain is predominantly associated with acute medical conditions or injuries, which tend to resolve within a short period. The causes of these types of pain were likely manageable or treatable within a limited timeframe, reflecting the effectiveness of medical interventions provided at the hospital. This is consistent with the types of conditions reported, such as malaria, trauma from car accidents, and infections, all of which are known to cause acute pain.

Among children, there was no significant difference in the prevalence of pain between males and females. This finding is in line with previous research, which suggests that, at a young age, gender differences in pain perception and expression are minimal [25]. However, as children grow older, social and cultural factors may begin to play a more significant role in pain expression, potentially leading to observed gender differences in older populations [26]. This could be due to several factors, including developmental changes in the nervous system and increased exposure to painful stimuli as infants grow and become more physically active [27]. Abdominal pain was the most prevalent among those who experienced pain, and this is consistent with research according to [8]. This emphasizes the need for comprehensive pain management approaches in children.

The study population of patients aged 17 years and above presented a complex pain profile characterized by both acute and chronic pain conditions. While acute pain, typically lasting less than three months, affected a few participants, the majority endured chronic pain. The largest proportion of adults experienced pain primarily due to ongoing medical conditions. Unlike infants and children, adults were more likely to experience chronic pain, which often led to pain-related disability, reduced mobility, and a decreased quality of life. The study also highlighted age as a significant factor, with older children and adults experiencing higher instances of chronic pain. The high prevalence of chronic pain in adults is consistent with previous studies that highlight the impact of long-term conditions such as arthritis and angina. There was a significant correlation between sex and pain, with females experiencing a higher prevalence of pain than males. Consistent with the findings of this study, the higher prevalence among women could be attributed to the fact that women report more frequent, more severe, and longer-lasting pain than males do in most cases [28]. Again, studies have shown that females are at higher risk for chronic pain disorders and exhibit greater sensitivity to noxious stimuli, with psychosocial factors, family influences and hormonal changes playing a key role [26].

Pharmacotherapy remains the primary management strategy for adults, similar to younger age groups. Pharmacological interventions were the primary pain management strategy across all age groups, probably because this was a hospital-based study where clinicians are more likely to use pharmacotherapy compared to other strategies in relieving pain. However, a multidisciplinary approach including physical therapy, psychological support, and lifestyle modifications is used for effective long-term management [29]. Preventive measures and adequate pharmacotherapy are not limited to infants and children but also adults. The treatment and management of pain in the study population primarily involved the use of analgesics, with ibuprofen and paracetamol being the most frequently administered. These medications are commonly used in pediatric populations due to their effectiveness and relative safety profiles. Paracetamol is often the first-line treatment for mild to moderate pain in infants, children and adults due to its analgesic and antipyretic properties and its favorable side effect profile [30].

The high rate of paracetamol use in this study is in line with the observation that most of the pain experienced by the infants and children may have been of mild to moderate intensity. Also, NSAIDs are prescribed for mild to severe pain in children because of their opioid-sparing action. Ibuprofen is another analgesic that is frequently used in pediatric care, particularly to treat pain that is related to inflammation, including that caused by infections or accidents [31]. Morphine and other stronger analgesics were also used, although less frequently. Morphine is typically reserved for severe pain due to its potency and the risk of side effects, including respiratory depression in infants. Despite the varying medications used, all infants in the study experienced positive treatment outcomes, although the degree of improvement varied. For a small portion of infants, pain was more difficult to manage, possibly due to factors such as the severity of the underlying condition, delayed treatment, or the development of tolerance to pain medications [32].

The results showcase significant limitations within pain evaluation, along with insufficient pain management methods between the youthful and older patient populations. Subjective pain evaluation methods require standardized pediatric tools such as Wong-Baker FACES and FLACC [14] for children to obtain effective pain management. Multidisciplinary pain management approaches, including physical therapy plus psychological support together with lifestyle restructuring, show the importance of adult pain management since chronic pain affects many people [29]. The study's findings highlight the importance of tailoring pain management strategies to different age groups, ensuring that both acute and chronic pain are effectively addressed.

This study provides one of the first comprehensive, age-stratified assessments of pain prevalence and management in a tertiary hospital setting in Ghana. By integrating standardized pain assessment tools across infants, children, and adults, it offers valuable insights into how pain presents and is treated across the human lifespan in a resource-constrained environment. The study highlights key disparities in pain relief outcomes, particularly among chronic pain patients, and underscores the limitations of pharmacotherapy as a standalone treatment. Importantly, it supports the need for age-specific and multidisciplinary approaches to pain management, contributing critical evidence to inform local healthcare policy, resource allocation, and the development of specialized pain clinics within sub-Saharan Africa. This study underscores an urgent need to create an integrated multidisciplinary pain center that will coordinate pain care services for inpatient and outpatient settings, offering both acute and chronic pain services. The center can also provide pain rehabilitation programs such as physical therapy, occupational therapy, and psychological support.

Despite its many strengths, this study's findings are limited by its cross-sectional design, which restricts causal interpretation, and the use of convenience sampling, which may affect generalizability. Pain assessment relied on subjective reports, introducing potential bias, especially among non-verbal participants. Non-pharmacological and psychosocial factors were underexplored, and the single site setting limits external applicability across other healthcare environments in Ghana and beyond.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates the widespread nature of pain across various age ranges. A high prevalence rate was found within the infants, where malaria, car accidents and jaundice stood as main causes. Patients between 4 and 16 years have the lowest pain prevalence. Adults had a high pain prevalence, with arthritis and angina as the primary causes; adult women were the majority in this group. Acute pain dominated the infant population, while adult patients mostly suffered from chronic pain. Most medical interventions for pain relief were primarily pharmacological. The therapeutic results varied widely; multiple patients reported only temporary relief from their pain issues, especially in patients with chronic pain.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing conflict of interest

Funding

Self-funded.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Louisa Armah, Andrew Agyei Kissi, David Nii Darko Dodoo, Maame Esi Amuquandoh, Angel Animal Tabiri, Chelsea Oshoro and Solomon Kweku Mensah for their technical support. Also, we appreciate the efforts of the Cape Coast Teaching Hospital staff.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the manuscript.

Authors Contributions

EO, OEE, and EOA were part of the conceptualization, design of the study, data analysis and final manuscript preparation. DA, IEM, JA, JKP, RK, MKG, and KO participated in data collection, analysis, drafting, and final manuscript preparation. All authors read, reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

References

2. IASP. Unrelieved Pain is a Major Global Healthcare Problem. Amazon. 2004; S3:1–4. https://s3.amazonaws.com/rdcms-iasp/files/production/public/Content/ContentFolders/GlobalYearAgainstPain2/20042005RighttoPainRelief/factsheet.pdf

3. Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, Fuchs PN, Turk DC. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull. 2007 Jul;133(4):581–624.

4. Hall RW, Anand KJ. Pain management in newborns. Clin Perinatol. 2014 Dec;41(4):895–924.

5. Larsson B, Sigurdson JF, Sund AM. Long-term follow-up of a community sample of adolescents with frequent headaches. J Headache Pain. 2018 Sep 4;19(1):79.

6. Schug SA, Palmer GM, Scott DA, Halliwell R, Trinca J. Acute pain management: scientific evidence, fourth edition, 2015. Med J Aust. 2016 May 2;204(8):315–7.

7. Board on Health Sciences Policy, Committee on Advancing Pain Research, & Care. Relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. National Academies Press; 2011.

8. King S, Chambers CT, Huguet A, MacNevin RC, McGrath PJ, Parker L, et al. The epidemiology of chronic pain in children and adolescents revisited: a systematic review. Pain. 2011 Dec;152(12):2729–38.

9. Cleeland CS. Pain assessment: the advantages of using pain scales in lysosomal storage diseases. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2002;91(439):43–7.

10. Stevens B, Yamada J, Ohlsson A, Haliburton S, Shorkey A. Sucrose for analgesia in newborn infants undergoing painful procedures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Jul 16;7(7):CD001069.

11. Bingham R, Mackersie A. Pediatric anaesthesia. In: Operative Pediatric Surgery: Sixth Edition, London: CRC Press; 2006. P. 15–23.

12. Chan AY, Ge M, Harrop E, Johnson M, Oulton K, Skene SS, et al. Pain assessment tools in paediatric palliative care: A systematic review of psychometric properties and recommendations for clinical practice. Palliat Med. 2022 Jan;36(1):30–43.

13. Friedrichsdorf SJ, Postier A, Eull D, Weidner C, Foster L, Gilbert M, et al. Pain Outcomes in a US Children's Hospital: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Survey. Hosp Pediatr. 2015 Jan;5(1):18–26.

14. Stevens BJ, Harrison D, Rashotte J, Yamada J, Abbott LK, Coburn G, et al. Pain assessment and intensity in hospitalized children in Canada. J Pain. 2012 Sep;13(9):857–65.

15. Ilari S, Nucera S, Passacatini LC, Caminiti R, Mazza V, Macrì R, et al. SIRT1: A likely key for future therapeutic strategies for pain management. Pharmacol Res. 2025 Mar;213:107670.

16. Phelan I, Carrion-Plaza A, Furness PJ, Dimitri P. Home-based immersive virtual reality physical rehabilitation in paediatric patients for upper limb motor impairment: a feasibility study. Virtual Real. 2023 Jan 14;27(4):1–16.

17. Kamki H, Kalaskar RR, Balasubramanian S. Evaluation of Effectiveness of Graphics Interchange Format and Wong-Baker FACES Pain Rating Scale as Pain Assessment Tool in Children. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2022 Jun 1;23(6):634–8.

18. Geneen LJ, Moore RA, Clarke C, Martin D, Colvin LA, Smith BH. Physical activity and exercise for chronic pain in adults: an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Apr 24;4(4):CD011279.

19. Reid KJ, Harker J, Bala MM, Truyers C, Kellen E, Bekkering GE, et al. Epidemiology of chronic non-cancer pain in Europe: narrative review of prevalence, pain treatments and pain impact. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011 Feb;27(2):449–62.

20. Herr K. Pain in the older adult: an imperative across all health care settings. Pain Manag Nurs. 2010 Jun;11(2 Suppl):S1–10.

21. Wong DL, Baker CM. Wong-Baker faces pain rating scale. Pain Management Nursing. 2012.

22. Harrison D, Joly C, Chretien C, Cochrane S, Ellis J, Lamontagne C, et al. Pain prevalence in a pediatric hospital: raising awareness during Pain Awareness Week. Pain Res Manag. 2014 Jan-Feb;19(1):e24–30.

23. Taddio A, Shah V, Atenafu E, Katz J. Influence of repeated painful procedures and sucrose analgesia on the development of hyperalgesia in newborn infants. Pain. 2009 Jul;144(1-2):43–8.

24. Olotu A, Fegan G, Wambua J, Nyangweso G, Leach A, Lievens M, et al. Seven-Year Efficacy of RTS,S/AS01 Malaria Vaccine among Young African Children. N Engl J Med. 2016 Jun 30;374(26):2519–29.

25. Ranger M, Johnston CC, Anand KJ. Current controversies regarding pain assessment in neonates. Semin Perinatol. 2007 Oct;31(5):283–8.

26. Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, Rahim-Williams B, Riley JL 3rd. Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009 May;10(5):447–85.

27. Grunau RE, Holsti L, Peters JW. Long-term consequences of pain in human neonates. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006 Aug;11(4):268–75.

28. McBeth J, Jones K. Epidemiology of chronic musculoskeletal pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2007 Jun;21(3):403–25.

29. Eccleston C, Blyth FM, Dear BF, Fisher EA, Keefe FJ, Lynch ME, et al. Managing patients with chronic pain during the COVID-19 outbreak: considerations for the rapid introduction of remotely supported (eHealth) pain management services. Pain. 2020 May;161(5):889–93.

30. Wong T, Stang AS, Ganshorn H, Hartling L, Maconochie IK, Thomsen AM, et al. Combined and alternating paracetamol and ibuprofen therapy for febrile children. Evid Based Child Health. 2014 Sep;9(3):675–729.

31. Rosenbloom BN, Rabbitts JA, Palermo TM. A developmental perspective on the impact of chronic pain in late adolescence and early adulthood: implications for assessment and intervention. Pain. 2017 Sep;158(9):1629–32.

32. Carter B, Harris J, Jordan A. How nurses use reassurance to support the management of acute and chronic pain in children and young people: An exploratory, interpretative qualitative study. Paediatr Neonatal Pain. 2021 Jan 25;3(1):36–44.