Abstract

Primary gastric mucormycosis is a rare but potentially lethal fungal infection due to the invasion of Mucorales into the gastric mucosa. It may result in high mortality due to increased risk of complications in immunocompromised patients. Common predisposing risk factors to develop gastric mucormycosis are prolonged uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, solid organ, or stem cell transplantation, underlying hematologic malignancy, and major trauma. Abdominal pain, hematemesis, and melena are common presenting symptoms. Diagnosis of gastric mucormycosis can be overlooked due to the rarity of the disease. A high index of suspicion is required for early diagnosis and management of the disease, particularly in immunocompromised patients. Radiological imaging findings are nonspecific to establish the diagnosis, and gastric biopsy is essential for histological confirmation of mucormycosis. Prompt treatment with antifungal therapy is the mainstay of treatment with surgical resection reserved in cases of extensive disease burden or clinical deterioration. We presented a case of acute gastric mucormycosis involving the body of stomach in a patient with no comorbidity, however he had post COVID status, admitted with hematemesis. Complete resolution of lesion was noted with medical treatment with intravenous amphotericin B.

Keywords

Mucormycosis, Primary gastric mucormycosis, Post COVID mucormycosis

Introduction

Gastric mucormycosis is an uncommon but severe fungal infection caused by Mucorales (a filamentous fungus) invasion into the stomach mucosa, with substantial mortality (up to 54%) in immunocompromised patients [1]. Mucormycosis (officially known as zygomycosis) is caused by the fungal class of zygomycetes, specifically Mucor, Rhizopus, or Rhizomucor species [1-3]. Upper respiratory tract, nasal or paranasal sinuses, skin, orbit, and brain are common sites of mucormycosis; however, the gastrointestinal tract is rarely infected [4]. Serologic indicators are vague; nonetheless, a biopsy from the afflicted site is the gold standard for establishing a mucormycosis histopathological diagnosis. On occasion, a positive culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on a biopsy specimen is necessary for diagnosis confirmation. The major option for treating gastric mucormycosis is medical care with antifungal therapy such as lipid formulation of amphotericin B, posaconazole, and newer drugs isavuconazole or triazole [5,6]. For individuals with severe disease, such as tissue necrosis, and those who present late, a combination of medicinal management and early surgical resection may improve disease outcome. We present a case of an immunocompetent person with stomach mucormycosis.

Case Presentation

A 43-year-old man with no systemic comorbidity presented to the emergency department because of 3 episodes of hematemesis and melena. The patient had experienced a history of COVID infection 1 month previously. He did not receive any steroid agents but was taking oral anticoagulant therapy because his D-dimer level was very high.

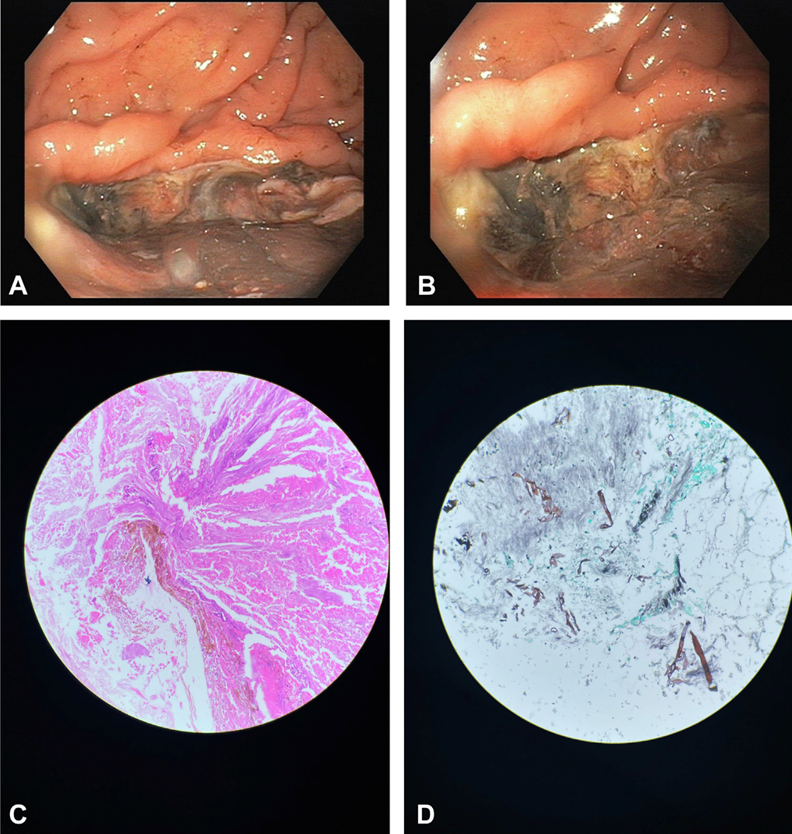

Upper GI endoscopy showed a large deep necrotic ulcer in the body of the stomach, with no active bleeding (Figures 1A and 1B). The patient’s condition improved with conservative management. Examination of a biopsy specimen with hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 1C) and Gomori methenamine silver stain (Figure 1D) showed fungal hyphae and evidence of gastric mucormycosis as a cause of the ulcer. The patient received a 4-week course of amphotericin B and is now doing well.

Discussion

Our case demonstrates an unexpected reason for GI bleeding in a COVID-19-recovered patient. Despite having a severe illness, he was effectively treated without surgery using anti-fungal medication alone.

Proton pump inhibitors did not relieve the patient's symptoms, so he underwent additional testing, including abdominal radiographic imaging and upper endoscopy. Radiological imaging results were inconclusive; however, EGD revealed numerous ulcerated sessile masses at increased curvature and stomach fundus. These mucosal lesions were covered in a massive greyish exudate, which raised the possibility of stomach mucormycosis. Histological examination, culture, and PCR of biopsy specimen validated the diagnosis of stomach mucormycosis.

Mucormycosis, which makes up around 7% of all documented cases, may only have gastrointestinal mucosal signs [1]. The stomach is the organ most frequently affected by gastrointestinal mucormycosis (67% of the time), followed by the colon (21%), small intestine (4%), and esophagus (2%) [1,4]. Through inhalation, ingestion, or injection of the spores, Mucorales can invade the body. The main way that Mucorales enter the gastrointestinal tract is through ingestion of the spores, which may be found in fermented milk, dried bread items, fermented porridges, and alcoholic beverages made from infected maize. And perhaps even from contaminated tongue depressors in healthcare settings [2]. Immunocompetent hosts can fend off Mucorales invasion after ingesting the spores into the gastrointestinal tract, while immunocompromised patients are unable to do so due to weakened immune systems and are more likely to experience severe infection. At present moment, it is unclear what causes infections in diabetic individuals, whether they have diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or not. The phagocytic dysfunction, poor chemotaxis, and improper intracellular destruction of Mucorales in the presence of an acidic environment of the stomach are the postulated mechanisms of gastric mucormycosis infection.

Around 2% to 13% of COVID-19 patients who are hospitalized have complications from acute gastrointestinal bleeding (GIB) [7]. However, mucormycosis of the gut has only sometimes been recorded as a cause of GI bleed in COVID-19 patients. Nasopharyngeal mucormycosis was discovered to aggravate the disease course during the second wave of this pandemic in India. Between 0.12 and 0.20 mucormycosis cases per 10,000 patients are thought to occur [8]. Around 7% of patients, particularly in immunocompromised hosts, can present with gastrointestinal signs, with the stomach being the most frequently afflicted organ in the GI tract. Our patient was treated solely with anti-fungal medications, despite the fact that anti-fungal therapy is typically the cornerstone of care for patients, although significant disorders may call for gastrectomy and debridement [9].

For their hyphal development during the invasion of the host cells, mucorales are iron-dependent. The rapid growth of Mucorales that results in fatal GI bleeding in COVID-19 may be attributed to inflammation-associated hyperferritinemia as well as bleeding from an earlier peptic ulcer [10].

The most frequent presenting symptom of gastric mucormycosis in the literature, according to numerous case reports, is abdominal discomfort, which is followed by hematemesis, melena, hematochezia, nausea, vomiting, dysphagia, and odynophagia [4]. Long-term uncontrolled diabetes mellitus with or without diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), solid organ or stem cell transplantation, underlying hematologic malignancy, major trauma, use of steroids, disseminated chronic infections, iron overload states, and severe neutropenia are the risk factors for developing gastric mucormycosis [4]. The most typical site of gastric mucormycosis is the gastric body.

A poor prognostic indicator of illness is the invasion of blood vessels beneath the mucosal surface, which can cause potentially fatal gastro-intestinal hemorrhage [4].

Radiological procedures like a CT scan or MRI of the abdomen frequently produce nonspecific results like a mass, reactive lymphadenopathy, and thickening of the mucosal wall, which calls for further examination and an endoscopic or surgical biopsy of the lesions. Stomach mucormycosis is characterized by ulcerated patchy mucosal lesions with overlaying greenish or greyish exudate found during an EGD; however, a biopsy of the lesions is required to distinguish it from stomach cancer [4]. EGD by itself is insufficient to provide a conclusive diagnosis; further testing using biopsy material is necessary. The most conclusive tests are those using culture and histopathology.

Patient outcomes and mortality rates were observed to be better with early antifungal medication initiation within 6 days. According to numerous studies, the mainstay treatment for mucormycosis is medical management with antifungal therapy; however, in a significant number of cases, surgical management with either debridement or gastrectomy of mucormycosis lesions may be necessary particularly in those with severe disease and numerous comorbidities. In hospitalized patients with mucormycosis, lipid formulations of amphotericin B (45% to 52%) and posaconazole (45%) are frequently used antifungal medicines. Posaconazole, an alternate antifungal, is advised for patients who have trouble tolerating amphotericin B and who run the risk of experiencing side effects such as nephrotoxicity. Posaconazole is an oral medication that can be used to treat stomach mucormycosis and is also long-term prophylactic. Although it is more well tolerated than amphotericin B, unpredictable medication absorption in patients with hematological malignancy and stomach mucormycosis is problematic and could lead to a breakthrough infection because of inadequate serum posaconazole concentration. In our case, liposomal amphotericin B, a first-line antifungal, was administered to the patient at first. It is necessary to perform ongoing EGD surveillance of gastrointestinal lesions to assess the therapeutic outcome. Isavuconazole and triazole, two more recent antifungal drugs, are also being used, but it is yet unknown how well they work to treat the condition.

Sometimes, anti-fungal medicine is insufficient for control, and some individuals need surgical intervention. In cases of significant disease, angioinvasion, mucosal necrosis, and those who have not responded to medicinal therapy, a combination of antifungal and surgical resection of lesions is advised. The spread of the illness and its complications, such as intestinal perforation, peritonitis, and major hemorrhage, may be avoided by aggressive surgical removal of necrotic lesions and negative tissue borders of fungal invasion [2].

Conclusion

A dangerous opportunistic fungal infection, mucormycosis can have a high fatality rate in people who are left untreated. For the early diagnosis and therapy of disease, especially in immunocompromised patients, doctors must have a high index of suspicion and awareness. In those who have equivocal results on radiological imaging, a typical presentation such as increased abdominal pain should be explored with a CT scan or MRI and EGD. The diagnosis of stomach mucormycosis is made through a biopsy of the suspected mucosal lesions. Given the invasive nature of the illness and high mortality, immediate medical care with antifungal medications like liposomal amphotericin B or posaconazole is required. To monitor the recovery from stomach mucormycosis and decide how long medicinal care will last, serial EGD may be necessary. In cases of inadequate response to antifungal medication and individuals with severe disease burden, resection of mucosal lesions using a mix of medical and surgical techniques is recommended.

References

2. Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, Roilides E, Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2012 Feb 1;54(suppl_1):S23-34.

3. Neofytos D, Horn D, Anaissie E, Steinbach W, Olyaei A, Fishman J, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of invasive fungal infection in adult hematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients: analysis of Multicenter Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH) Alliance registry. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2009 Feb 1;48(3):265-73.

4. Uchida T, Okamoto M, Fujikawa K, Yoshikawa D, Mizokami A, Mihara T, et al. Gastric mucormycosis complicated by a gastropleural fistula: a case report and review of the literature. Medicine. 2019 Nov;98(48):e18142.

5. Marty FM, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Cornely OA, Mullane KM, Perfect JR, Thompson GR, et al. Isavuconazole treatment for mucormycosis: a single-arm open-label trial and case-control analysis. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2016 Jul 1;16(7):828-37.

6. Kontoyiannis DP, Lewis RE. How I treat mucormycosis. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2011 Aug 4;118(5):1216-24.

7. Lin L, Jiang X, Zhang Z, Huang S, Zhang Z, Fang Z, et al. Gastrointestinal symptoms of 95 cases with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Gut. 2020 Jun 1;69(6):997-1001.

8. Kontoyiannis DP, Yang H, Song J, Kelkar SS, Yang X, Azie N, et al. Prevalence, clinical and economic burden of mucormycosis-related hospitalizations in the United States: a retrospective study. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2016 Dec;16(1):730.

9. Sharma D. Successful management of emphysematous gastritis with invasive gastric mucormycosis. BMJ Case Reports CP. 2020 Feb 1;13(2):e231297.

10. Baldin C, Ibrahim AS. Molecular mechanisms of mucormycosis—The bitter and the sweet. PLoS pathogens. 2017 Aug 3;13(8):e1006408.