Abstract

Background: Cancer therapy related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) poses a significant challenge to the treatment of cancer patients receiving cardiotoxic chemotherapeutic regimen like anthracyclines and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) inhibitors like trastuzumab. This systematic review evaluated the efficacy and safety of conventional heart failure medications—angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), and beta-blockers (BBs)—in preventing CTRCD in adults undergoing such therapies.

Method: Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines, 12 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 1,571 patients were analyzed from PubMed, Scopus and Embase. Primary outcomes included changes in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), biomarkers like Troponin, atrial/brain natriuretic peptide (ANP/BNP) level and electrocardiograph (ECG), before and after chemotherapy. Secondary outcomes included total mortality and development of symptomatic heart failure, either necessitating treatment initiation or hospitalization.

Results: Several studies demonstrated cardioprotective effects after the use of the aforementioned medications. Biomarker-guided approaches using troponin yielded inconsistent results, and combination therapy did not consistently outperform monotherapy. Most interventions were well tolerated, with few adverse events such as bradycardia and hypotension.

Conclusion: Conventional heart failure medications such as ACEIs, ARBs, and BBs may offer selective benefit. However, current evidence is heterogeneous and does not support their routine prophylactic use. Future large-scale, long-term trials with standardized cardiac endpoints and patient-specific risk stratification are essential to guide clinical practice in cardio-oncology.

Keywords

Cancer therapy related cardiac dysfunction, Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, Angiotensin receptor blockers, Beta-blockers, Anthracycline, Trastuzumab, Heart failure

Abbreviations

LV EDV: Left Ventricular End Diastolic Volume; GLS: Global Longitudinal Strain; LV EDD: Left Ventricular End Diastolic Diameter; LV ESD: Left Ventricular End Systolic Diameter; FS: Fractional Shortening; DNA: Deoxyribonucleic Acid; NO: Nitric Oxide; CHOP: Cyclophosphamide Hydroxydauorubicin Oncovin Prednisone; ECOG PS: Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group Performance Status; CMR: Cardiac Magnetic Resonance; SAVE HEART: proSpective registry for prediction And preVEntion of cHEmotherapy-induced cARdiotoxicity in patients with breasT cancer

Introduction

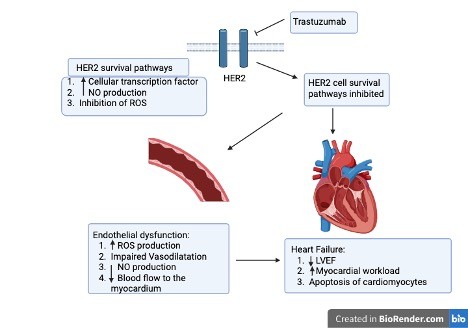

Cancer therapy-related cardiac dysfunction (CTRCD) is a well-recognized complication in oncology and remains a major clinical concern, particularly in patients treated with anthracyclines or human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) inhibitors such as trastuzumab. These drugs have transformed cancer outcomes, but their potential for cardiotoxicity can result in permanent myocardial injury, impaired quality of life, and, in severe cases, premature death [1–3]. Anthracyclines form the backbone of many treatment regimens for both hematologic malignancies and solid tumors, while HER2 inhibitors have become essential in managing aggressive HER2-positive cancers [4–7]. Although their therapeutic targets differ, both can damage the myocardium through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, mitochondrial injury, and disruption of cardiomyocyte signaling (see Figures 1 and 2) [5,7–10]. CTRCD is often defined as a drop in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of at least 10% to a value below 50%. Clinically, it may present with arrhythmias, pericardial effusion, myocardial ischemia, or frank heart failure [11,12]. The onset can be rapid during chemotherapy itself and emerge within the first year after treatment or appear many years later as late-onset cardiomyopathy [13–17].

Recognizing these risks, current cardio-oncology guidelines recommend regular cardiac surveillance and, in high risk patients, prophylactic initiation of conventional heart-failure therapies such as angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), or beta-blockers (BBs), particularly, in patients with baseline cardiovascular risk factors including hypertension, diabetes or concurrent cardiac diseases and patients receiving high cumulative doses or multiple cardiotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs [18–20]. While these agents are proven in established heart failure, their ability to prevent chemotherapy-related cardiac injury is less certain. The available evidence is limited by small sample sizes, differences in trial endpoints, heterogeneous patient populations and exclusion of high-risk patients from the trials [21–23]. It is still unclear whether one class should be preferred over another for primary prevention, or whether certain patient subgroups gain particular benefit. In this systematic review, through incorporating randomized controlled trials (RCTs) conducted in 2024–25, we present the most up-to-date synthesis of RCTs on prophylactic use of ACEIs, ARBs, and BBs in anthracycline and trastuzumab induced cardiotoxicity in adult cancer patients. In addition to analyzing cardiac outcomes, our review uniquely explores biomarker-guided risk stratification to determine whether high-risk patients may selectively benefit from cardioprotective therapy. By bringing together most comprehensive and recent evidence up to July 2025, we aim to clarify the strength of current data, highlight areas where knowledge remains limited, and help guide both future research and everyday clinical decision-making in cardio-oncology.

Methodology

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 guidelines [24]. The protocol was not registered in PROSPERO due to project timeline constraints.

Literature search

A comprehensive search of PubMed, Scopus, and Embase was performed from database inception to 1st July 2025. Search terms combined controlled vocabulary (MeSH/Emtree) and free-text words related to the intervention, population, and outcomes. The Boolean strategy applied to PubMed was: (Cardioprotective medication) OR (ACE inhibitor) OR (Enalapril) OR (ARB) OR (Beta blocker) OR (Carvedilol) OR (Metoprolol)) AND ((Cancer) OR (Lymphoma) OR (Chemotherapy) OR (Doxorubicin) OR (Anthracycline) OR (Trastuzumab) OR (Herceptin)) AND (cardiotoxicity) OR (Heart failure) OR (cardiomyopathy) OR (ejection fraction).

Equivalent search strings were adapted for each database. Manual reference screening of all included studies and relevant reviews was also undertaken to identify additional eligible trials.

Eligibility criteria

We included RCTs and observational studies published in English involving adult cancer patients undergoing anthracycline and/or trastuzumab based chemotherapy and using ACEIs and/or ARBs and/or BBs as cardioprotective medications with at least one quantifiable measure of cardiotoxicity (see Table 1). Non-randomized trials, conference abstracts, unpublished studies, non-peer-reviewed data, reviews, editorials and animal studies were excluded. Studies involving pediatric population, adult patients with significant pre-existing cardiac comorbidities and published in non-English language were excluded as well. Additionally, studies using cardioprotective medications other than the medications of interest such as statin or studies reporting only surrogate endpoints without clinical or imaging-based cardiac outcomes were not included in this systematic review.

|

Particulars |

Inclusion Criteria |

|

Study type |

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and observational studies |

|

Participants |

Adult patients (2:18 years) undergoing chemotherapy regimens consisting of anthracyclines and/or trastuzumab |

|

Intervention |

Prophylactic or concurrent administration of conventional heart failure medications:

|

|

Comparison |

Placebo or no cardioprotective therapy, in addition to standard chemotherapy |

|

Outcomes |

At least one quantifiable measure of cardiotoxicity, such as:

|

|

Language |

Articles published in English |

The initial database search for relevant studies generated a total of 539 articles that met the initial search criteria. Of these, 92 duplicates were removed, leaving 447 records to be screened. Based on our eligibility criteria, four investigators independently performed title-abstract screening of those 447 articles using the Rayyan platform leaving 35 articles. Seven observational studies found during initial search were screened and excluded as they did not meet eligibility criteria. After four researchers' full-text assessment of those 35 articles and conflict resolution by two others, twelve studies were finally included in our systematic review. All other studies were excluded due to either wrong population (n=10), wrong drug (n=10), wrong study design (n=9) or wrong study outcome (n=6) as depicted in Figure 3.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The construction of the data extraction excel sheet was performed by two reviewers, and four reviewers extracted data independently. Two additional reviewers performed the data revision and second check. The investigators collected the first author, study design, location, number of patients, baseline patient characteristics (age, gender, cancer type), chemotherapy and cardioprotective regimens across study arms. Primary outcomes included change in LVEF (%), cardiac biomarkers such as troponin and ANP/BNP level and electrocardiograph (ECG) changes before and after chemotherapy. Secondary outcomes included total mortality and development of symptomatic heart failure either necessitating treatment initiation or hospitalization. Two reviewers assessed each of the included studies for bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 quality assessment tool and any conflict was resolved by another reviewer [25].

Data synthesis

Due to marked heterogeneity in outcomes a quantitative meta-analysis could not be performed, and findings are presented narratively.

Results

Characteristics of the included studies

The sum of patients included across all twelve studies was 1,571 adults with concomitant cancer treated with chemotherapeutic regimens consisting of anthracyclines and/or trastuzumab. The study characteristics are depicted in Tables 2 and 3. ACEIs were studied as either combination or comparison drug to BBs mainly in hematological malignancies. On the other hand, ARBs were studied both as monotherapy and combination and/or comparison to BBs mainly in breast cancer. Both showed mixed results and their effects in preserving LVEF were not consistent across the studies. BBs were more extensively studied among all cardioprotective medications both as monotherapy and combination and/or comparison to ARBs/ACEIs mainly in breast cancer and mixed cancer groups providing strongest evidence of cardioprotection. Increased doses of BBs were not associated with better cardioprotection. Oncology trials of combination therapy produced mixed results. Biomarker-guided risk stratification gave inconclusive reports. All medications were reported to be well tolerated among patients.

|

Study ID |

Design |

Location

|

Duration |

Patient number - Intervention - Control |

Conclusion |

|

Bosch et al., 2013 [30] |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Spain |

6 months |

Total: 90 - Enalapril + carvedilol: 45 - Control: 45 |

Combined treatment with enalapril and carvedilol may prevent left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with malignant hemopathies undergoing intensive chemotherapy, but larger studies are needed to confirm the clinical relevance of this strategy. |

|

Pituskin et al., 2011 [34] |

Parallel 3-arm, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study |

Canada |

12 months |

Total: 159 - Perindopril: 53 - Bisoprolol: 53 - Control: 53 |

Perindopril and bisoprolol were well tolerated in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) positive early breast cancer who received trastuzumab and protected against cancer therapy related declines in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), however trastuzumab mediated left ventricular remodeling was not prevented by these pharmacotherapies. |

|

Nakamae et al., 2005 [29] |

Randomized Controlled Trial |

Osaka City University Medical Foundation, Japan |

7 days |

Total: 40 - Valsartan: 20 - Control: 20 |

Valsartan significantly prevents changes in cardiac markers associated with acute cyclophosphamide hydroxydauorubicin oncovin prednisone (CHOP) induced cardiotoxicity, except for the elevation in atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), suggesting a potential role for angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) in preventing cardiotoxicity but requiring further research on long-term effects. |

|

Gulati et al., 2016 [26] |

Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled and 2×2 factorial study design

|

Akershus University Hospital, Norway |

10–61 weeks depending on the chemotherapy regimen |

Total: 130 - Candesartan + metoprolol: 28 - Candesartan + placebo: 32 - Metoprolol + placebo: 30 - Placebo + placebo: 30 |

Candesartan significantly alleviates the decline in LVEF associated with adjuvant breast cancer therapy, while metoprolol did not show a short-term beneficial effect, and suggests potential long-term benefits in reducing ventricular dysfunction risk. |

|

Heck et al., 2021 [35] |

Randomized, 2×2 factorial, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial |

Akershus University Hospital, Norway |

10–61 weeks |

Total: 120 - Candesartan + metoprolol: 30 - Candesartan + placebo: 30 - Metoprolol + placebo: 30 - Placebo + placebo: 30 |

Candesartan during adjuvant therapy for breast cancer did not prevent reduction in LVEF at 2 years but was associated with modest reduction in left ventricular end diastolic volume (LV EDV) and preserved global longitudinal strain (GLS), suggesting that a broadly administered cardioprotective approach may not be required in most patients with early breast cancer without preexisting cardiovascular disease. |

|

Abuosa et al., 2018 [31] |

Prospective, randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled dose-ranging study

|

King Faisal Cardiac Centre in King Abdulaziz Medical City-Jeddah, Saudi Arabia |

6 months |

Total: 154 - Placebo: 38 - Carvedilol 6.25 mg: 41 - Carvedilol 12.5 mg: 38 - Carvedilol 25 mg: 37 |

Carvedilol may prevent deterioration in LVEF in cancer patients treated with doxorubicin, with this effect possibly not being dose-related, and provides further evidence for its protective role against anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. |

|

Kalay et al., 2006 [36] |

Prospective, randomized, single-blind, placebo-controlled study |

Erciyes University Medical School, Turkey |

6 months |

Total: 50 - Carvedilol: 25 - Control: 25 |

Prophylactic use of carvedilol in patients receiving anthracycline therapy may protect both systolic and diastolic functions of the left ventricle. |

|

Georgakopoulos et al., 2010 [27] |

Prospective, randomized controlled trial

|

Greece |

36 months

|

Total: 147 - Metoprolol group: 42 - Enalapril group: 43 - Control group: 40

|

Metoprolol and enalapril did not significantly reduce the risk of cardiotoxicity in patients treated with doxorubicin, although there was a trend towards lower incidence of heart failure and subclinical cardiotoxicity in the treatment groups, particularly with metoprolol. |

|

Lee et al., 2021 [37] |

Randomized phase III study Post-hoc analysis of SAVE HEART study

|

The Catholic University of Korea, Korea

|

At least 12 months |

Total: 238 - Candesartan: 82 - Carvedilol: 70 - Control: 43 - Total randomized: 195 |

Subclinical cardiotoxicity is prevalent in breast cancer patients without cardiovascular risk treated with doxorubicin, and low-dose candesartan may be effective in preventing early decreases in LVEF, with its protective effect persisting over a year, although further large-scale trials are needed to confirm these findings. |

|

Jung et al., 2025 [38] |

Single-center, prospective, randomized, open-label Phase I clinical trial

|

University of Pennsylvania, United States |

12 months |

Total: 68 - Low risk, nonrandomized: 49 - Elevated risk, usual care: 6 - Elevated risk, carvedilol: 13 |

This Phase 1 trial demonstrated the feasibility, safety, and tolerability of risk-guided cardioprotection with carvedilol in breast cancer patients and highlighted the need for additional strategies to optimize non-treatment intervention trials, particularly during global health crises. |

|

Avila et al., 2018 [39] |

Prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study

|

Heart Failure Department of Heart Institute (InCor) and the Cancer Institute, Sa?o Paulo, Brazil

|

20 weeks |

Total: 200 - Carvedilol: 96 - Placebo: 96 |

Carvedilol did not prevent early onset LVEF reduction but significantly reduced troponin levels and diastolic dysfunction, indicating some protective effects against cardiotoxicity. |

|

Henriksen et al., 2023 [28] |

Multicenter, prospective, randomized, open-label, blinded end- point trial nested within an observational cohort study |

South-East Scotland Research Ethics Committee, United Kingdom

|

Variable, but it includes the time from randomization to 6 months post-chemotherapy. |

Total: 175 - Cardioprotection: 29 - Standard care: 28 -Nonrandomized: 118 |

The study found no strong evidence that early cardioprotection therapy with combined candesartan and carvedilol prevented decline in LVEF in patients with breast cancer or non-Hodgkin lymphoma, questioning the benefit of current guidelines and highlighting poor tolerance to the therapy. |

|

Study ID |

Patient characteristics |

Cancer type |

Chemotherapy regimen |

Cardioprotective medication |

|

Bosch et al., 2013 [30] |

- Age: 18-70 years - Gender: 43% female, 57% male - Baseline left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) >50% and in sinus rhythm |

Hematological malignancies |

Anthracycline based regimen |

Enalapril and Carvedilol combination regimen |

|

Pituskin et al., 2011 [34] |

- Women aged >18 years - No history of heart failure, cardiomyopathy, or uncontrolled hypertension - Baseline LVEF ≥50% |

human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 positive (HER2+) breast cancer |

Trastuzumab |

- Perindopril - Bisoprolol |

|

Nakamae et al., 2005 [29]

|

- Age: 24–70 years (mean 56 years) - Gender: 52.5% female, 47.5% male - ECOG PS: 0 to 1 - Total serum bilirubin <2.0 mg/dL, serum creatinine level <2.0 mg/dL - LVEF >50% - Not pregnant or lactating - No history of chronic or acute heart failure, other cardiac diseases, cirrhosis, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, cerebral vascular accidents, severe psychopathy, contraindication to angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) |

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

|

Anthracycline based regimen |

Valsartan

|

|

Gulati et al., 2016 [26] |

- Women aged 18–70 years - ECOG PS: 0–1 - Serum creatinine <1.6 mg/dL - No symptomatic heart failure, clinically significant coronary artery disease, valvular heart disease, significant arrhythmias, or conduction delays - No concurrent use or intolerance to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), ARBs and beta-blockers (BBs) - Baseline LVEF ≥50% - Not pregnant or breastfeeding |

Breast cancer |

Anthracycline based regimen |

- Candesartan and Metoprolol combination regimen - Candesartan monotherapy - Metoprolol monotherapy

|

|

Heck et al., 2021 [35] |

- Women aged 18–70 years - Cardiovascular risk factors: diabetes (1.7%), hypertension (6.7%) and smoking (17.5%) - Baseline LVEF ≥50% - No serious comorbidities |

Breast cancer |

Anthracycline based regimen |

- Candesartan and Metoprolol combination regimen - Candesartan monotherapy - Metoprolol monotherapy

|

|

Abuosa et al., 2018 [31] |

- Age: >16 years - Gender: 72.7% female, 27.3% male - Cardiovascular risk factors: hypertension (11.7%), diabetes mellitus (17.5%) and dyslipidemia (5.2%) - Baseline LVEF ≥50% |

Multiple (mainly breast cancer and non-Hodgkin lymphoma) |

Anthracycline based regimen

|

Carvedilol of different doses

|

|

Kalay et al., 2006 [36] |

- Age: 32.8–60.8 years - Gender: 86% female, 14% male - No history of congestive heart failure, cardiomyopathy of any type, coronary arterial disease, moderate or severe mitral or aortic valve disease, any contraindication to Carvedilol, bundle branch block, thyroid function disorder, or another comorbid disease - Not on ACEIs, ARBs, BBs and diuretics - Baseline LVEF ≥50% |

Multiple (mainly breast cancer and lymphoma) |

Anthracycline based regimen |

Carvedilol |

|

Georgakopoulos et al., 2010 [27] |

- Age: 49 years on average - Gender: 50% women, 50% men - Cardiovascular risk factors: hypertension (24%), diabetes mellitus (15.2%), hypercholesterolemia (28%), family history of cardiac disease (13.6%), smoking (42.4%) - Baseline LVEF ≥50% |

Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

Anthracycline based regimen |

- Metoprolol - Enalapril |

|

Lee et al., 2021 [37] |

- Female patients of age over 18 years - No prior history of smoking, coronary artery disease, hypertension, diabetes and dyslipidemia - Baseline LVEF ≥50% |

Breast cancer |

Anthracycline based regimen |

- Candesartan - Carvedilol |

|

Jung et al., 2025 [38] |

- Women aged ≥18 years - Cardiovascular risk factors: smoking (32%), hypertension (21%), diabetes mellitus (7%), hyperlipidemia (25%), coronary artery disease (12%), arrhythmia (6%) - Not pregnant or lactating - No stage IV breast cancer, contraindications to Carvedilol, no current beta-blocker therapy - Baseline LVEF ≥50% |

Breast cancer |

Anthracycline and/or trastuzumab therapy

|

Carvedilol |

|

Avila et al., 2018 [39] |

- Women aged ≥18 years - Cardiovascular risk factors: hypertension (6.2%), diabetes mellitus (4.7%), hypercholesterolemia under statin treatment (4.2%), any history of smoking (26%) - Baseline LVEF ≥50% |

Breast cancer |

Anthracycline based regimen |

Carvedilol |

|

Henriksen et al., 2023 [28] |

- Age: >18 years - Gender: 87% female, rest was male - Cardiovascular risk factors: diabetes (2.3%), hypertension (9.1%), coronary disease (2.9%), any history of smoking (39.4%) - Concomitant cardiovascular medication prescription (9.7%) - Baseline LVEF ≥50% |

Breast cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma |

Anthracycline based regimen |

Candesartan and carvedilol combination regimen |

Risk of bias assessment

The Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.0 RevMan quality assessment tool was used to construct the risk of bias graph and risk of bias summary depicted in Figure 4. Most studies were methodologically sound: seven trials had a low risk of bias in all domains. In four trials, there were gaps in reporting, particularly around how randomization was done or how blinding was maintained, so we judged these as having “unclear” risk in at least one area. Only one trial was rated as high risk, mainly because more than 20% of participants were lost to follow-up, and the losses weren’t balanced between groups. This raised concerns that the missing data could have influenced the results. Overall, selective reporting did not appear to be a problem. However, differences in how cardiac outcomes were measured—for example, using echocardiography in some trials and cardiac MRI in others and the fact that some outcome assessors were not blinded could have introduced some subtle measurement bias.

Discussion

This systematic review evaluates the efficacy and safety of ACEIs, ARBs, BBs, and their combinations in preventing CTRCD in cancer patients receiving anthracycline- and/or trastuzumab-based chemotherapy. It draws data and synthesizes findings from twelve RCTs. The endpoints of these trials predominantly included changes in LVEF and cardiac biomarkers such as cardiac troponins and natriuretic peptides. Current evidence paints a mixed picture: while ACEIs, ARBs, and BBs can help preserve cardiac function in some patients, their benefits are neither consistent nor universal, underscoring the need for targeted rather than routine use. In Gulati et al.'s trial, adjuvant breast cancer patients on candesartan showed a smaller LVEF decline after chemotherapy than controls (−0.8% vs −2.6%, p=0.026) [26]. In contrast, Georgakopoulos et al. found no significant benefit, with 12-month LVEF changes of −2.4%, −1.3%, and −1.0% in the metoprolol, enalapril, and control groups, respectively [27]. The use of biomarkers, particularly troponin, as a stratification tool for initiating cardioprotective therapy was explored with varying success. For example, in the Cardiac CARE trial of 175 anthracycline-treated cancer patients, troponin levels during chemotherapy were used to classify participants as high- or low-risk for cardiotoxicity [28]. In the trial, the failure to demonstrate a statistically significant difference in CMR measured LVEF changes across all three groups after six months of chemotherapy, challenges the clinical utility of biomarker-guided strategies and further questions if troponin elevations truly predict clinically significant cardiac dysfunction. A significant challenge in interpreting these RCTs lies in the heterogeneity of outcomes assessed. While LVEF remains the most reported endpoint, its insensitivity to early myocardial dysfunction limits its use as a sole measure of cardiotoxicity. Several trials used a multimodal approach, assessing cardiac biomarkers, ECG changes, and imaging measures beyond LVEF. In Nakamae et al’s trial, outcomes were grouped into three categories: 1) biomarkers (ANP/BNP), 2) echocardiographic parameters (LVEF, LVEDD, LVESD, FS, E/A ratio, deceleration time), and 3) ECG measures (QTc interval and dispersion) [29]. The clinical relevance of these surrogate markers, particularly in the absence of long-term follow-up data on symptomatic heart failure or mortality, remains debatable. The variability in imaging techniques (ECG and CMR), endpoints, and follow-up durations further complicates cross-trial comparisons. Oncology trials of combination therapy have produced mixed results. In Bosch et al.’s trial, enalapril plus carvedilol led to a significantly smaller LVEF decline than placebo after six months (−0.17% vs −3.28%, p=0.04) [30]. However, direct comparisons with monotherapy are few; among the 12 RCTs, only the PRADA trial included both combination and monotherapy arms, but group-specific LVEF data were unavailable, preventing such analysis [26].

Chemotherapy regimen and dose-related subgroup analysis was insufficiently explored. Patients receiving higher cumulative anthracycline doses or additional cardiotoxic chemotherapeutic drugs like Trastuzumab may derive greater benefit from cardioprotection, however, no study stratified results by dose intensity or Trastuzumab addition. In all the twelve RCTs reviewed, the medications used for cardioprotection were generally well tolerated among patients. The incidence of adverse effects such as hypotension, bradycardia, or renal dysfunction was low [26,31]. Notably, some trials reported that cardioprotective therapy allowed cancer treatment to proceed without interruptions, potentially improving outcomes by reducing delays or dose reductions related to cardiac issues [32,33]. This review has several limitations. Meta-analysis was not possible due to heterogeneity in outcome measures, limiting the precision of effect estimates. Heterogeneity in anthracycline formulations, unclear cumulative doses and the addition of Trastuzumab or other chemotherapeutic agents likely contributed to inconsistent results across the studies. Additionally, the follow up duration of most RCTs was within 6–12 months over a range of one week to 36 months. This variability affected outcome detection as well. Variability in CTRCD definitions and imaging modalities further hindered data aggregation and interpretation. Most trials had small sample sizes and excluded patients with pre-existing cardiovascular disease or low (<50%) LVEF at baseline limiting external validity of our study since these high-risk groups are common in real-world practice and are most likely to benefit from preventive therapy. Short follow up duration (6–12 months on average) is insufficient to detect late-onset cardiotoxicity, which may manifest years after chemotherapy completion and likely underestimates long-term cardiovascular risk and the potential benefits of cardioprotective therapy.

Future progress in cardio-oncology will require large, well-powered studies with long-term follow-up to assess feasibility, cost-effectiveness, and patient-centered outcomes of cardioprotective strategies. Standardizing CTRCD definitions and monitoring protocols, adopting risk-based patient selection, and integrating multidisciplinary cardio-oncology pathways into cancer centers will be crucial for translating research into practice.

Conclusion

This systematic review highlights both the promise and the limitations of current pharmacologic strategies for preventing chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity. While conventional heart failure medications such as ACEIs, ARBs and BBs offer modest protection in select populations, the variability in outcomes underscores the need for individualized, evidence-based approaches. Robust, long-term trials incorporating clinical endpoints and precision risk stratification are essential to inform future guidelines and optimize cardiovascular outcomes in cancer patients.

References

2. Curigliano G, Lenihan D, Fradley M, Ganatra S, Barac A, Blaes A, et al. ESMO Guidelines Committee. Electronic address: clinicalguidelines@esmo.org. Management of cardiac disease in cancer patients throughout oncological treatment: ESMO consensus recommendations. Ann Oncol. 2020 Feb;31(2):171–90.

3. Alvarez-Cardona JA, Ray J, Carver J, Zaha V, Cheng R, Yang E, et al. Cardio-Oncology Leadership Council. Cardio-Oncology Education and Training: JACC Council Perspectives. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020 Nov 10;76(19):2267–81.

4. de Melo Gagliato D, Jardim DL, Marchesi MS, Hortobagyi GN. Mechanisms of resistance and sensitivity to anti-HER2 therapies in HER2+ breast cancer. Oncotarget. 2016 Sep 27;7(39):64431–46.

5. Albanell J, Codony J, Rovira A, Mellado B, Gascón P. Mechanism of action of anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies: scientific update on trastuzumab and 2C4. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2003;532:253–68.

6. Barbieri MA, Sorbara EE, Cicala G, Santoro V, Cutroneo PM, Franchina T, et al. Adverse Drug Reactions with HER2-Positive Breast Cancer Treatment: An Analysis from the Italian Pharmacovigilance Database. Drugs Real World Outcomes. 2022 Mar;9(1):91–107.

7. Muntasell A, Cabo M, Servitja S, Tusquets I, Martínez-García M, Rovira A, et al. Interplay between Natural Killer Cells and Anti-HER2 Antibodies: Perspectives for Breast Cancer Immunotherapy. Front Immunol. 2017 Nov 13;8:1544.

8. Dal Ben D, Palumbo M, Zagotto G, Capranico G, Moro S. DNA topoisomerase II structures and anthracycline activity: insights into ternary complex formation. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13(27):2766–80.

9. Dhingra R, Margulets V, Kirshenbaum LA. Molecular mechanisms underlying anthracycline cardiotoxicity: Challenges in cardio-oncology. Cardio-Oncology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA. 2017:25–34.

10. Baselga J, Albanell J. Mechanism of action of anti-HER2 monoclonal antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2001;12 Suppl 1:S35–41.

11. Perez IE, Taveras Alam S, Hernandez GA, Sancassani R. Cancer Therapy-Related Cardiac Dysfunction: An Overview for the Clinician. Clin Med Insights Cardiol. 2019 Jul 29;13:1179546819866445.

12. Truong J, Yan AT, Cramarossa G, Chan KK. Chemotherapy-induced cardiotoxicity: detection, prevention, and management. Can J Cardiol. 2014 Aug;30(8):869–78.

13. Bisoc A, Ciurescu D, Rădoi M, Tântu MM, Rogozea L, Sweidan AJ, et al. Elevations in High-Sensitive Cardiac Troponin T and N-Terminal Prohormone Brain Natriuretic Peptide Levels in the Serum Can Predict the Development of Anthracycline-Induced Cardiomyopathy. Am J Ther. 2020 Mar/Apr;27(2):e142–50.

14. Zamorano JL, Lancellotti P, Rodriguez Muñoz D, Aboyans V, Asteggiano R, Galderisi M, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. 2016 ESC Position Paper on cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity developed under the auspices of the ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines: The Task Force for cancer treatments and cardiovascular toxicity of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J. 2016 Sep 21;37(36):2768–801.

15. Dang CT, Yu AF, Jones LW, Liu J, Steingart RM, Argolo DF, et al. Cardiac Surveillance Guidelines for Trastuzumab-Containing Therapy in Early-Stage Breast Cancer: Getting to the Heart of the Matter. J Clin Oncol. 2016 Apr 1;34(10):1030–3.

16. Seidman A, Hudis C, Pierri MK, Shak S, Paton V, Ashby M, et al. Cardiac dysfunction in the trastuzumab clinical trials experience. J Clin Oncol. 2002 Mar 1;20(5):1215–21.

17. Broder H, Gottlieb RA, Lepor NE. Chemotherapy and cardiotoxicity. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2008 Spring;9(2):75–83.

18. Henry ML, Niu J, Zhang N, Giordano SH, Chavez-MacGregor M. Cardiotoxicity and Cardiac Monitoring Among Chemotherapy-Treated Breast Cancer Patients. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 Aug;11(8):1084–93.

19. Keshavarzian E, Sadighpour T, Mortazavizadeh SM, Soltani M, Motevalipoor AF, Khamas SS, et al. Prophylactic Agents for Preventing Cardiotoxicity Induced Following Anticancer Agents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Clinical Trials. Rev Recent Clin Trials. 2023;18(2):112–22.

20. Alexandre J, Cautela J, Ederhy S, Damaj GL, Salem JE, Barlesi F, et al. Cardiovascular Toxicity Related to Cancer Treatment: A Pragmatic Approach to the American and European Cardio-Oncology Guidelines. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020 Sep 15;9(18):e018403.

21. Lewinter C, Nielsen TH, Edfors LR, Linde C, Bland JM, LeWinter M, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of beta-blockers and renin-angiotensin system inhibitors for preventing left ventricular dysfunction due to anthracyclines or trastuzumab in patients with breast cancer. Eur Heart J. 2022 Jul 14;43(27):2562–9.

22. Elghazawy H, Venkatesulu BP, Verma V, Pushparaji B, Monlezun DJ, Marmagkiolis K, et al. The role of cardio-protective agents in cardio-preservation in breast cancer patients receiving Anthracyclines ± Trastuzumab: a Meta-analysis of clinical studies. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2020 Sep;153:103006.

23. Gao Y, Wang R, Jiang J, Hu Y, Li H, Wang Y. ACEI/ARB and beta-blocker therapies for preventing cardiotoxicity of antineoplastic agents in breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev. 2023 Nov;28(6):1405–15.

24. Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021 Apr;88:105906.

25. Sterne JAC, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, et al. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019 Aug 28;366:l4898.

26. Gulati G, Heck SL, Ree AH, Hoffmann P, Schulz-Menger J, Fagerland MW, et al. Prevention of cardiac dysfunction during adjuvant breast cancer therapy (PRADA): a 2 × 2 factorial, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind clinical trial of candesartan and metoprolol. Eur Heart J. 2016 Jun 1;37(21):1671–80.

27. Georgakopoulos P, Roussou P, Matsakas E, Karavidas A, Anagnostopoulos N, Marinakis T, et al. Cardioprotective effect of metoprolol and enalapril in doxorubicin-treated lymphoma patients: a prospective, parallel-group, randomized, controlled study with 36-month follow-up. Am J Hematol. 2010 Nov;85(11):894–6.

28. Henriksen PA, Hall P, MacPherson IR, Joshi SS, Singh T, Maclean M, et al. Multicenter, Prospective, Randomized Controlled Trial of High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin I-Guided Combination Angiotensin Receptor Blockade and Beta-Blocker Therapy to Prevent Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity: The Cardiac CARE Trial. Circulation. 2023 Nov 21;148(21):1680–90.

29. Nakamae H, Tsumura K, Terada Y, Nakane T, Nakamae M, Ohta K, et al. Notable effects of angiotensin II receptor blocker, valsartan, on acute cardiotoxic changes after standard chemotherapy with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone. Cancer. 2005 Dec 1;104(11):2492–8.

30. Bosch X, Rovira M, Sitges M, Domènech A, Ortiz-Pérez JT, de Caralt TM, et al. Enalapril and carvedilol for preventing chemotherapy-induced left ventricular systolic dysfunction in patients with malignant hemopathies: the OVERCOME trial (preventiOn of left Ventricular dysfunction with Enalapril and caRvedilol in patients submitted to intensive ChemOtherapy for the treatment of Malignant hEmopathies). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013 Jun 11;61(23):2355–62.

31. Abuosa AM, Elshiekh AH, Qureshi K, Abrar MB, Kholeif MA, Kinsara AJ, et al. Prophylactic use of carvedilol to prevent ventricular dysfunction in patients with cancer treated with doxorubicin. Indian Heart J. 2018 Dec;70 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):S96–S100.

32. Cardinale D, Colombo A, Lamantia G, Colombo N, Civelli M, De Giacomi G, et al. Anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy: clinical relevance and response to pharmacologic therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Jan 19;55(3):213–20.

33. Seicean S, Seicean A, Alan N, Plana JC, Budd GT, Marwick TH. Cardioprotective effect of β-adrenoceptor blockade in patients with breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy: follow-up study of heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2013 May;6(3):420–6.

34. Pituskin E, Haykowsky M, Mackey JR, Thompson RB, Ezekowitz J, Koshman S, et al. Rationale and design of the Multidisciplinary Approach to Novel Therapies in Cardiology Oncology Research Trial (MANTICORE 101--Breast): a randomized, placebo-controlled trial to determine if conventional heart failure pharmacotherapy can prevent trastuzumab-mediated left ventricular remodeling among patients with HER2+ early breast cancer using cardiac MRI. BMC Cancer. 2011 Jul 27;11:318.

35. Heck SL, Gulati G, Ree AH, Schulz-Menger J, Gravdehaug B, Røsjø H, et al. Rationale and design of the prevention of cardiac dysfunction during an Adjuvant Breast Cancer Therapy (PRADA) Trial. Cardiology. 2012;123(4):240–7.

36. Kalay N, Basar E, Ozdogru I, Er O, Cetinkaya Y, Dogan A, et al. Protective effects of carvedilol against anthracycline-induced cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Dec 5;48(11):2258–62.

37. Lee M, Chung WB, Lee JE, Park CS, Park WC, Song BJ, et al. Candesartan and carvedilol for primary prevention of subclinical cardiotoxicity in breast cancer patients without a cardiovascular risk treated with doxorubicin. Cancer Med. 2021 Jun;10(12):3964–73.

38. Jung W, Hubbard RA, Smith AM, Ko K, Huang A, Wang J, et al. Risk-guided cardioprotection with carvedilol in patients with breast cancer (CCT guide): a phase 1 randomized clinical trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2025 Jun;211(2):293–305.

39. Avila MS, Ayub-Ferreira SM, de Barros Wanderley MR Jr, das Dores Cruz F, Gonçalves Brandão SM, Rigaud VOC, et al. Carvedilol for Prevention of Chemotherapy-Related Cardiotoxicity: The CECCY Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018 May 22;71(20):2281–90.