Abstract

Background: Modern treatment of breast cancer depends mainly on the expression of biomarkers such as estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR) and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). However, a change of receptors was not uncommon during the disease progression. Here we aim to evaluate the impact on clinical outcome from the conversion of receptors in primary tumor and recurrent or metastatic lesions.

Materials and methods: We retrospectively reviewed a cohort of patients who received breast cancer treatment in our hospital during 2012 to 2019. The study populations were stratified according to consistency or discordance of tumor phenotypes. The clinical outcomes were compared between the two groups in post-recurrence survival and overall survival.

Results: A total of 100 patients were confirmed with recurrence or metastasis with available specimen from recurrent lesion. The rates of discordance were 18%, 16%, 10% for ER, PR, and HER2, respectively. Thirty-eight percent patients had subtyping changed, whereas the other 62% patients presented the same subtype during progression. A better PRS was found in concordantly PR positive group compared with those with PR loss in recurrent tumors (not reached vs. 27 months, p=0.0465). Moreover, the low-HER2 group presented a worse survival outcome (PRS 27 months vs. 40 months, p=0.40) compared to whose HER2 status changed from negative to positive, although without significant difference.

Conclusion: Discordant receptors between primary and recurrent tumors exist in some patients with recurrence or metastasis. The recurrent lesions should be biopsied whenever feasible to tailor the appropriate therapy.

Keywords

Breast neoplasm, erbB-2, Hormone Receptors, Discordance, Survival

Abbreviations

ER: Estrogen Receptor; PR: Progesterone Receptor; HER2: Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2; TNBC: Triple Negative Breast Cancer; OS: Overall Survival; PRS: Post-Recurrence Survival; IHC: Immunohistochemistry; ISH: In situ Hybridization; ASCO: American Society of Clinical Oncology; CAP: College of American Pathologists; NCCN: National Comprehensive Cancer Network; EDTA: Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid; DNA: Deoxyribonucleic Acid; CI: Confidence Interval; SIRT1: Sirtuin Type 1

Introduction

Breast cancer leads the highest incidence of cancers in women worldwide. The modern treatment of breast cancer is diverse in different subtypes allocated mainly by expression of biomarkers such as estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). These important receptors are applied clinically in prediction of outcome and as the guidance of treatment decision. Despite the advance of therapeutic modality, at least one-half of early breast cancers encounter recurrence which continues to occur even long after primary diagnosis [1,2]. Once recurrence, the strategy of treatment may follow the previous allocation from primary tumor or change to a different way due to the potential of receptor discordance between primary tumor and recurrent/metastatic lesions.

Receptor discordance or conversion refers to the change of ER, PR, and HER2 expression. The discordance results in challenge in clinical decision making, assessment of prognosis and overall patient management. Previous literature had addressed the viewpoint on the discordance of ER, PR, and HER2 between primary and metastatic tumors. From a meta-analysis, the discordance rate was observed in 19.3% for ER, 30.9% for PR, and 10.3% for HER2 [3]. Another meta-analysis study also reported the similar percentage of discordance, 14%, 21%, and 10% in ER, PR and HER2 expression, respectively [4]. Receptor discordance can alter the therapeutic landscape dramatically. For example, a primary ER-positive tumor lacking ER expression in recurrent lesions may no longer respond to endocrine therapy and need a shift to chemotherapy or other treatment modalities. Conversely, the acquisition of HER2 positivity in a recurrent tumor might open new avenues for targeted HER2 therapies, which were not previously indicated.

This discordance somehow manifests as a loss or gain of receptor expression, representing the variable behavior of tumor or resistance to previous therapies. Therefore, such aggressive tumors may indicate a poor prognosis or reduced survival outcome. In earlier analysis, loss of the receptor expression had been considered as the main determinant of poor outcome. The loss of HR and the loss of HER2 resulted in a worse post-recurrence and overall survival, compared with the corresponding concordant-positive cases [5]. On the other hand, Walter et al. proposed that gain in HER2 positivity was associated with an improved overall survival [6]. The authors also found the same conclusion whereas loss of HR positivity presented with an inferior overall survival. Meanwhile, a large scale study in French disclosed that loss of HR status was significantly associated with a risk of death while gain of HR and HER2 discordance was not [7]. The potential of receptors conversion has generated a consensus to re-biopsy recurrent tumors if tissue available. But the viewpoint of impact on survival outcomes remains in debate. Here we aim to review the discordant rate between primary and recurrent tumors in our series and interpret the impact of receptor discordance on survival outcome of breast cancer patients.

Subjects and Methods

Study population

Under the approval of the Institutional Review Board of Taipei Veterans General Hospital (IRB number # 2025-02-001BC), patients with breast cancer were diagnosed and their records were retrospectively reviewed. The patients were sourced from two databases. Initially, breast cancer patients who were diagnosed between 2013 and 2018 were retrieved from a prospectively collected database with the criteria including stage 0 to III with evidence of recurrence. Cases with other malignancy, absence of primary pathology report, or incomplete data were excluded. Furthermore, breast cancer patients registered in the Big Data Center of Taipei Veterans General Hospital from 2012 to 2022 (IRB number # 2024-04-014AC) were also screened with the same criteria (Figure 1). Patients diagnosed until 2019 were selected for complete five-year follow up period. Subsequently, duplicates were removed after comparison between the two cohorts. Among patients with evidence of recurrence or metastasis, patients who had available biopsy results with complete ER, PR, and HER2 status were enrolled into this study. The primary objective is to observe the discordant rate of receptors and subtypes, whereas the secondary endpoint is the impact of loss or gain of receptors on post-recurrence or overall survival.

Figure 1. The flow chart showing enrollment of study patients.

Pathology assessment

The interpretation was performed by the experienced pathologist (HCY) in our institute following the standard protocols mentioned in our previous publications. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) stains for ER (clone 6F11; Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK; 1:100), PR (clone 16; Leica Biosystems, Newcastle, UK; 1:150) with ≥1% of tumor cells exhibiting nuclear staining are regarded as positive for ER and PR. HER2 (A0485; Dako, Glostrup, Den- mark; 1:900) IHC positivity, score 3+, is defined by complete intense membrane staining in >10% of tumor cells. Reflex ISH testing by fluorescence ISH (PathVysion HER2 DNA Probe Kit; Abbott Laboratories, Des Plaines, IL, USA) is performed for cases with equivocal HER2 IHC results (score 2+). Patients with average HER2 copy numbers of ≥6 signals/cell or a HER2 ISH ratio (HER2 gene signals to chromosome 17 centromere signals) of ≥2 are regarded as ISH-positive according to the ASCO/CAP guidelines [8].

Definition of receptor discordance

Discordance of receptors refers to a change in the positivity of receptors, between the primary tumor and associated recurrent or metastatic lesions. Subtype discordance refers to changes in subtypes which are classified according to criteria listed in Appendix 1. If a patient has more than two metastases, the first biopsy site of the metastases is selected.

Outcome and statistical analysis

The discordance rate of receptor and subtype between primary and recurrent/metastatic site was analyzed by McNemar test. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the time of initial breast cancer diagnosis to the date of death or last consultation. Post-recurrence survival (PRS) was defined as the time between the date of recurrence confirmed by imaging study or by pathological confirmation and the date of death or last consultation. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate the cumulative incidence of OS and PRS and Log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test were used for comparisons. Statistical software is MedCalc® Statistical Software version 20.111.

Results

Demographics and clinical features

A total of 183 patients with evidence of recurrence were identified from the first prospectively collected cohort. On the other hand, there were 83 patients retrieved from a series of 7,442 breast cancer patients registered in the Big Data Center after removal of duplicates in the two cohorts. Among these 221 patients who had initial stage 0 to III and evidence of recurrence or metastasis, a total of 100 patients with available biopsy from the recurrent tumors were analyzed in this study. The demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients were shown in Table 1. The most common site for re-biopsy was locoregional lesions (52%), which includes the ipsilateral breast, axilla, chest wall, skin, and regional lymph nodes. For distant metastases, liver biopsies were the most frequent (13%), followed by lung biopsies (9%). The least common biopsy sites were bone (5%) and brain (5%).

|

|

N (%) |

|

Laterality |

|

|

Right |

43 (43%) |

|

Left |

56 (56%) |

|

Bilateral |

1 (1%) |

|

Stage |

|

|

0 |

3 (3%) |

|

I |

24 (24%) |

|

II |

40 (40%) |

|

III |

33 (33%) |

|

Primary tumor subtype |

|

|

Luminal A |

24 (24%) |

|

Luminal B1 |

14 (14%) |

|

Luminal B2 |

14 (14%) |

|

HER2-enrich |

24 (24%) |

|

TNBC |

24 (24%) |

|

Receptor discordance |

|

|

ER |

18 (18%) |

|

ER gain |

4 (4%) |

|

ER loss |

14 (14%) |

|

PR |

16 (16%) |

|

PR gain |

2 (2%) |

|

PR loss |

14 (14%) |

|

HER2 |

10 (10%) |

|

HER2 gain |

4 (4%) |

|

HER2 loss |

6 (6%) |

|

Discordance in any of the receptors |

36 (36%) |

|

Totally concordance |

64 (64%) |

|

Subtype discordance |

38 (38%) |

|

Biopsy sites |

|

|

Locoregional (chest wall, ipsilateral breast) |

52 (52%) |

|

Contralateral breast |

5 (5%) |

|

Lung |

9 (9%) |

|

Liver |

13 (13%) |

|

Bone |

5 (5%) |

|

Brain |

5 (5%) |

|

Others |

11 (11%) |

|

Median overall survival |

65.0 months (95% CI 49.0-84.0) |

|

Median post-recurrence survival |

33.0 months (95% CI 27.0-60.0) |

|

Time to recurrence/metastasis |

24.5 months |

| ER: Estrogen Receptor; PR: Progesterone Receptor; HER2: Human Epidermal Receptor | |

Receptor concordance

The proportions of discordance for ER, PR, and HER2 were 18%, 16%, and 10%, respectively. Among these, ER and PR discordance were predominantly characterized by receptor loss, whereas HER2 did not show much difference between gain and loss. There were 25.9% (14/54) ER-positive tumors lost the expression of ER in recurrent tumors, whereas 36.8% (14/38) PR-positive tumors had loss of PR. The discordance between the primary and recurrent/metastatic sites were significantly prominent in ER and PR status (p=0.03 and p<0.005, respectively), as shown in Table 2. In patients with discordance of hormone receptors, 82.4% (28/34) presented ER or PR loss. However, the HER2 status did not show the significant difference in discordance.

|

|

Recurrent/metastatic ER- |

Recurrent/metastatic ER+ |

|

|

|

|

|

Primary ER- |

42 |

4 |

|

Primary ER+ |

14 |

40 |

|

|

|

p=0.03 |

|

|

Recurrent/metastatic PR- |

Recurrent/metastatic PR+ |

|

Primary PR- |

60 |

2 |

|

Primary PR+ |

14 |

24 |

|

|

|

p=0.00 |

|

|

Recurrent/metastatic HER2- |

Recurrent/metastatic HER2+ |

|

Primary HER2- |

59 |

4 |

|

Primary HER2+ |

6 |

31 |

|

|

|

p=0.07 |

| ER: Estrogen Receptor; PR: Progesterone Receptor; HER2: Human Epidermal Receptor 2; -: Negative; +: Positive; * McNemar test | ||

Change of subtypes

Subtype discordance was observed in 38% of the patients. Figure 2 presented a Sankey diagram illustrating the flow of phenotype from primary to recurrent tumors. The most common subtype discordance changed from luminal A to luminal B1. The second most common change was from luminal B2 to HER2. Patients whose primary subtype was HER2 (83.3%) or TNBC (79.2%) mostly maintained their original subtype upon recurrence or metastasis, with a lower proportion of discordance. The luminal B2 subtype exhibited the greatest variation in subtype discordance (9/14, 64.3%).

Figure 2. The Sankey diagram depicting changes in subtypes.

The impact on survival outcome

The median overall survival for these 100 patients was 65 months (95% CI 49.0-84.0). The median post-recurrence survival was 33 months (95% CI 27.0-60.0). The patients were categorized into the concordance or discordance group based on change of receptors. The OS and PRS between the two groups were shown in Table 3. The two groups across the ER, PR, or HER2 status revealed no significant difference in OS and PRS.

|

|

ER concordance |

ER discordance |

Log-rank test |

|

OS |

74 |

58 |

p=0.44 |

|

PRS |

34 |

27 |

p=0.37 |

|

|

PR concordance |

PR discordance |

|

|

OS |

63 |

79 |

p=0.92 |

|

PRS |

33 |

31 |

p=0.77 |

|

|

HER2 concordance |

HER2 discordance |

|

|

OS |

63 |

81 |

p=0.45 |

|

PRS |

32 |

56 |

p=0.53 |

|

|

Subtype concordance |

Subtype discordance |

|

|

OS |

63 |

68 |

p=0.86 |

|

PRS |

32 |

34 |

p=0.90 |

|

|

Concordance in all receptors |

Discordance in any of receptors |

|

|

OS |

63 |

68 |

p=0.81 |

|

PRS |

33 |

32 |

p=0.74 |

| OS: Overall Survival (months); PRS: Post-Recurrence Survival (months); ER: Estrogen Receptor; PR: Progesterone Receptor; HER2: Human Epidermal Receptor 2 | |||

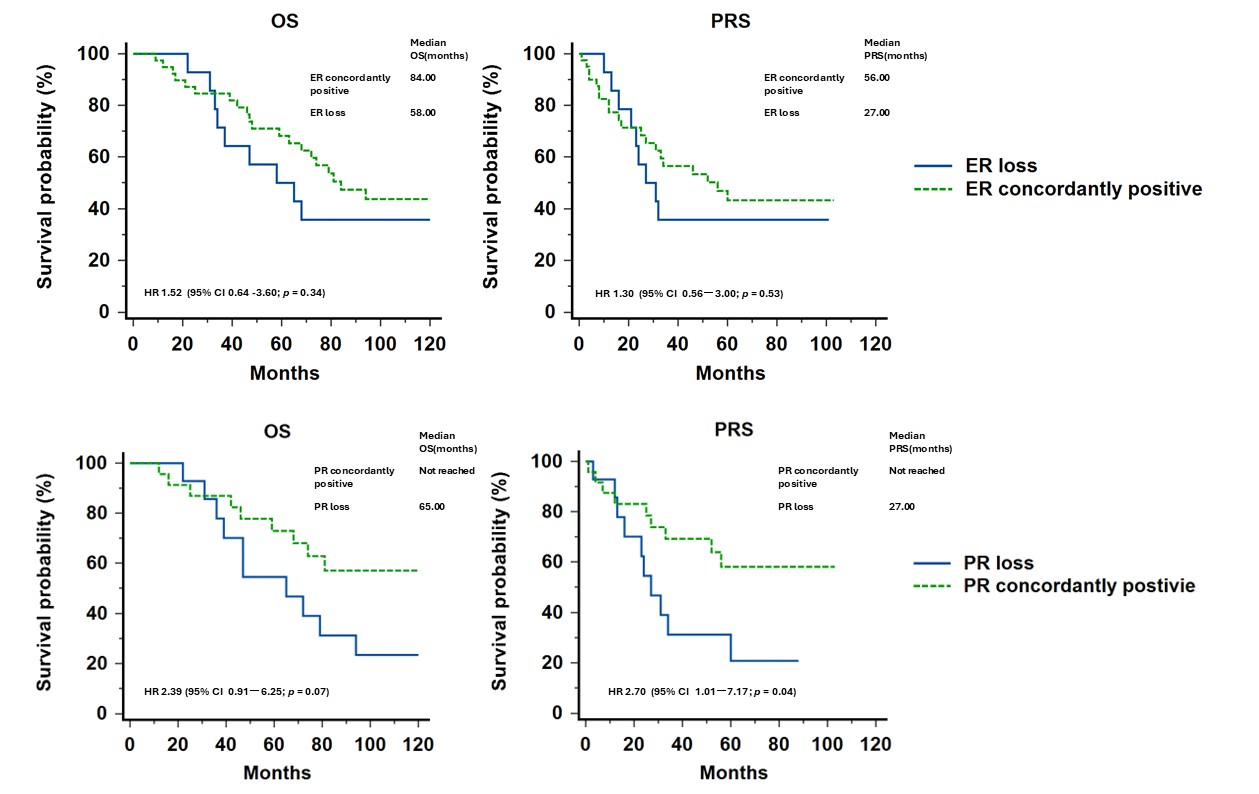

To minimize the impact on survival from expression of HR or HER2 per se, we further divided the concordance group into concordantly positive and concordantly negative groups. The OS and PRS among each group were illustrated in Figure 3. The ER or PR concordantly positive groups both showed a better survival compared with the discordance group or concordantly negative group, although without significance statistically. Furthermore, we compared the survival outcomes of patients with concordantly positive HR versus patients who had HR loss (Figure 4). Although no statistically significant difference was found in OS and PRS for ER, a better PRS was found in concordantly PR positive group compared with those with PR loss during progression (not reached vs. 27 months, p=0.0465).

Figure 3. Survival curves of concordant positive or negative expression, discordance of each receptor. (The survival of each group is listed in Supplement 1).

Figure 4. Survival curves of concordant positive expression or loss of hormone receptors.

HER2 gain in IHC scores

Moreover, we performed a subgroup analysis for the change of HER2 IHC scores. Some patients (9/13, 69.23%) were found to have different IHC scores of HER2 during progression but this may not shift the HER2 from negative to positive. Patients had recurrent tumors with gain of HER2 IHC scores were allocated in two groups. The first group consisted of those with increased IHC scores, such as 0 to 1+, 0 to 2+/ISH-, 1+ to 2+/ISH-, which were still regarded as HER2 negative. Those with HER2 IHC scores 1+ or 2+/ISH- were so-called low-HER2 tumors. Another group included the tumors with increased IHC scores which converted the HER2 status from negative to positive, also termed the HER2 discordantly positive group. As illustrated in Supplement 2, although there was no statistically significant difference in PRS between the two groups, the low-HER2 group presented a worse survival outcome (PRS 27 months vs. 40 months, p=0.40) compared to the HER2 discordantly positive group.

Discussion

The discordance rates of receptors in our series were 18% for ER, 16% for PR, and 10% for HER2, respectively. The incidence of receptor conversion varied largely between literature and our finding is similar to that observed in meta-analysis or review research [3,4,9,10]. Therefore, receptors discordance is potential when the relapse happens, and it reminds the clinicians to re-biopsy whenever tumor sample is available.

Most conversion presents as a positive to a negative receptor that may limit the application of previous hormone therapy or target therapy. In a previous literature addressed by the ASCO panelists, they reviewed several meta-analyses and found that pooled estimates for the absolute frequency of changes from positive to negative ranged from 5.7% to 9.5% for ER status and 17% to 24% for PR status. Pooled estimates for the absolute frequency of change from negative to positive ranged from 3% to 8.8% for ER status and from 6.9% to 7.3% for PR status [11]. In our series, we also demonstrated the similar finding that most discordance cases, 77.7% (14/18) for ER and 87.5% (14/16) for PR, experienced loss rather than gain of receptor expression. However, when the allocation of subtypes relies on expression of receptors, either gain or loss has impacts on treatment strategies. Our study revealed that 38% of patients presented subtypes discordance and the majority comes from loss of hormone receptors.

Most guidelines encouraged to obtain the recurrence or metastasis lesions to confirm their subtypes and determine the strategy of treatment [11-13]. However, it is not always easy to obtain tissue everywhere. According to our study, the easiest tissues to obtain are ipsilateral breast and chest wall, followed by liver and lung metastasis, and very few may have brain or bone tissue. Among them, if the acquisition of bone lesions is possible, the issue of IHC staining needs to be deliberate because of the mineral content of bone surface which is not easy for staining and usually requires a decalcification process. However, the decalcification process leads to a certain degree of damage on the cell which also destroys the receptors on the cell membrane surface [14]. Therefore, it deserves careful interpretation on the expression of receptors for bone lesions even the tissue is feasible to be harvested. Recently, some experts proposed a new strategy for decalcification by EDTA which is demonstrated as a reliable approach to assess receptor status [15,16]. In our study, there were originally 221 cases of recurrence and metastasis, but only 103 cases were able to obtain tissue. For patients whose tissue cannot be obtained, the original tumor tissue can only be used to determine the direction of treatment. If the actual receptor is inconsistent or the subtype has changed, the choice of anti-cancer regimens will be quite different or even opposite. Therefore, when the therapeutic effect is not as good as expected, receptor discordance should be taken into consideration as the reason of treatment failure.

The heterogeneity of tumor is another concern for receptor conversion. Whether biopsy sample could represent the whole tumor landscape is also debated [17]. For hormone receptors, we hereby defined negative as receptor expression <1%, in consistent with ASCO/CAP guideline [18]. But ER or PR positive tumors may involve a wide range of expression from 1 to 100%. The intratumor heterogeneity not only affects tumor response but also makes a challenge in the assessment of receptors [19]. The mechanisms underlying receptor discordance are not fully understood but are believed to involve tumor heterogeneity, clonal selection, and genetic or epigenetic alterations during disease progression and treatment [20,21]. The other proposed mechanism for phenotype switching is intrinsic or induced cell plasticity which may be contributed by several processes such as epigenetic modifications, regulation of transcription factors, activation or suppression of key signaling pathways, as well as epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and tumor microenvironment [22].

Research continues to explore the extent and causes of receptor discordance, aiming to develop predictive markers and more personalized treatment strategies. Liquid biopsies, which analyze circulating tumor cells or cell-free DNA in the blood [23,24], represent a promising non-invasive approach to monitor receptor status and detect changes over time. These advances could enable more dynamic and responsive treatment adjustments, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

Whether the receptor discordance directs the destiny of metastatic breast cancer patients remains controversial. Theoretically, once the subtype changed, the treatment may be adjusted according to the new phenotype and expected to overcome the resistance from cell plasticity. In a previous review [11], one study reported no significant differences in outcomes between patients with concordant versus discordant receptors [25], whereas four studies reported shorter survival for those with specific discordances [26-29]. In our study, the OS or PRS across the ER, PR or HER2 status revealed no significant differences regardless of whether the receptor status changed or not. The possible reasons may be limited sample size, shorter period for follow up in our series, or treatment adjusted along with the changed receptor status. However, evidence on survival outcomes is lacking in the literature for those with discordant receptors whose treatment is guided by the phenotype of the metastases rather than that of the primary tumors. On the other hand, the patients with concordantly positive HR showed a trend of better outcome in OS and PRS, although no significant difference was found in statistics. Also worthy of note is that a better PRS was observed in concordantly PR positive group compared to those who experienced PR loss during disease progression. This finding supported the notion that loss of PR may represent the obstacle of treatment in recurrence or metastatic breast cancers.

Our study revealed that there were 14 patients presenting PR loss in their recurrent tumors. Among patients with discordant subtypes, 9 of 38 (23.7%) patients had conversion of subtypes from luminal A to B1. The PR is impressed as a marker of functional ER and expected to be responsive to hormone therapy in HR positive tumors. If ER becomes nonfunctional and unable to produce PR, the growth and survival of tumor cells may not be dependent on estrogen stimulation [30]. Tumors with PR loss often have worse outcomes in both primary and metastatic lesions and may also reflect resistance to treatment [31]. A meta-analysis had demonstrated that patients with loss of ER/PR in recurrent tumors presented a significantly shorter OS compared to those with concordant positive receptors [32]. In our series, ER loss did not affect the survival outcomes, but PR loss was associated with worse PRS compared to concordantly positive PR expression. Although the difference in overall survival was not statistically significant, there was a trend toward poorer survival in patients with PR loss in recurrent tumors. Loss of PR may result from a complex mechanism, including ESR1 gene mutation, alteration of ESR1 transcriptional regulators [33], decreased transcription of the PGR gene [34], or PTEN inactivating mutations [35]. In addition, the silent information regulation factor 1 (Sirtuin Type 1, SIRT1) had been demonstrated to play a critical role in progestin resistance in endometrial cancer [36]. Upregulation of SIRT1 in progestin-resistant cells correlated with downregulation of PR. Through inactivation of the p53 pathway, SIRT1 represses estrogen signaling, ligand-independent ERα-mediated transcription, and promotes the expression of multi-drug resistance associated protein in tamoxifen-resistant breast cancer cells [37,38]. The change leads to different treatment strategies. In hormone responsiveness, endocrine therapy is the mainstay of treatment choice for metastatic or recurrent tumors, whereas the luminal B subtype may have resistance to endocrine therapy alone and need intervention of chemotherapy or cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 inhibitors [39]. The change of receptors is a critical issue that underscores the dynamic nature of cancer biology. Our research supported that if a recurrent tumor represented PR loss, more aggressive therapy should be taken into consideration to potentially improve the otherwise poor prognosis.

The limitations of our study include its retrospective design and small sample size, which ruled out those metastatic or recurrent tumors without available samples. The exclusion may lead to a selection bias in the analysis of incidence and impact of receptors discordance. However, despite the small sample size, we still found a significant difference in survival outcomes associated withPR loss from primary to recurrent tumors. These findings contribute to a better understanding of the biology of breast cancer tumorigenesis and warrant further investigation.

Conclusion

In summary, our study provided evidence on the discordance of receptors between primary and recurrent tumors. The receptor conversion may result in a worse outcome in the scenario of PR loss. Tissue samples from recurrent or metastatic site is essential to tailor optimal treatment in advanced breast cancers.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the subject matter or materials discussed in this article.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from Taipei Veterans General Hospital (V113C-190, V114C-221). This study is also supported by Dr. Morris Chang (ABMRD002) and Melissa Lee Cancer Foundation (MLCF_V113_A11304, MLCF_V114_A11406).

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to all colleagues who contributed to this study. The study was conceived and designed by Tsung-Yen Hsieh and Yi-Fang Tsai. Data acquisition was performed collaboratively by Jiun-I Lai, Chun-Yu Liu, Chin-Jung Feng, Chi-Cheng Huang, Chih-Yi Hsu, Yen-Shu Lin, Ta-Chung Chao, Pei-Ju Lien, Jen-Hwey Chiu, Ling-Ming Tseng, and Yi-Fang Tsai. Tsung-Yen Hsieh, Jen-Hwey Chiu, and Yi-Fang Tsai were responsible for data analysis and interpretation. The manuscript was drafted by Tsung-Yen Hsieh and Yi-Fang Tsai, and critically revised by Jen-Hwey Chiu, Ling-Ming Tseng, and Yi-Fang Tsai. The authors are grateful to the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and the Big Data Center of Taipei Veterans General Hospital for their technical support and provision of data resources.

References

2. Dowling RJO, Kalinsky K, Hayes DF, Bidard FC, Cescon DW, Chandarlapaty S, et al. Toronto Workshop on Late Recurrence in Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer: Part 1: Late Recurrence: Current Understanding, Clinical Considerations. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019;3:pkz050.

3. Schrijver WAME, Suijkerbuijk KPM, van Gils CH, van der Wall E, Moelans CB, van Diest PJ. Receptor Conversion in Distant Breast Cancer Metastases: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110:568-80.

4. Yeung C, Hilton J, Clemons M, Mazzarello S, Hutton B, Haggar F, et al. Estrogen, progesterone, and HER2/neu receptor discordance between primary and metastatic breast tumours-a review. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2016;35:427-37.

5. Dieci MV, Barbieri E, Piacentini F, Ficarra G, Bettelli S, Dominici M, et al. Discordance in receptor status between primary and recurrent breast cancer has a prognostic impact: a single-institution analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:101-8.

6. Walter V, Fischer C, Deutsch TM, Ersing C, Nees J, Schütz F, et al. Estrogen, progesterone, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 discordance between primary and metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;183:137-44.

7. Grinda T, Joyon N, Lusque A, Lefèvre S, Arnould L, Penault-Llorca F, et al. Phenotypic discordance between primary and metastatic breast cancer in the large-scale real-life multicenter French ESME cohort. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2021;7:41.

8. Wolff AC, Somerfield MR, Dowsett M, Hammond MEH, Hayes DF, McShane LM, et al. Human Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor 2 Testing in Breast Cancer: ASCO-College of American Pathologists Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:3867-72.

9. Dowling GP, Keelan S, Cosgrove NS, Daly GR, Giblin K, Toomey S, et al. Receptor Discordance in Metastatic Breast Cancer; a review of clinical and genetic subtype alterations from primary to metastatic disease. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2024;207(3):471-76.

10. Gogia A, Deo SVS, Sharma D, Phulia RK, Thulkar S, Malik PS, et al. Discordance in Biomarker Expression in Breast Cancer After Metastasis: Single Center Experience in India. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1-8.

11. Van Poznak C, Somerfield MR, Bast RC, Cristofanilli M, Goetz MP, Gonzalez-Angulo AM, et al. Use of biomarkers to guide decisions on systemic therapy for women with metastatic breast cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2695-704.

12. Cardoso F, Costa A, Norton L, Cameron D, Cufer T, Fallowfield L, et al. 1st international consensus guidelines for advanced breast cancer (ABC 1). Breast. 2012;21:242–52.

13. Carlson RW, Allred DC, Anderson BO, Burstein HJ, Edge SB, Farrar WB, et al. Metastatic breast cancer, version 1.2012: Featured updates to the NCCN guidelines. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10:821-9.

14. Maclary SC, Mohanty SK, Bose S, Chung F, Balzer BL. Effect of Hydrochloric Acid Decalcification on Expression Pattern of Prognostic Markers in Invasive Breast Carcinomas. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2017; 25:144-9.

15. van Es SC, van der Vegt B, Bensch F, Gerritse S, van Helden EJ, Boon E, et al. Decalcification of Breast Cancer Bone Metastases With EDTA Does Not Affect ER, PR, and HER2 Results. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:1355-60.

16. Washburn E, Tang X, Caruso C, Walls M, Han B. Effect of EDTA decalcification on estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor immunohistochemistry and HER2/neu fluorescence in situ hybridization in breast carcinoma. Hum Pathol. 2021;117:108-14.

17. Chen J, Wang Z, Lv Q, Du Z, Tan Q, Zhang D, et al. Comparison of Core Needle Biopsy and Excision Specimens for the Accurate Evaluation of Breast Cancer Molecular Markers: a Report of 1003 Cases. Pathol Oncol Res. 2017;23:769-75.

18. Allison KH, Hammond MEH, Dowsett M, McKernin SE, Carey LA, Fitzgibbons PL, et al. Estrogen and Progesterone Receptor Testing in Breast Cancer: ASCO/CAP Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:1346-66.

19. Zardavas D, Irrthum A, Swanton C, Piccart M. Clinical management of breast cancer heterogeneity. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015; 12: 381-94.

20. Pusztai L, Viale G, Kelly CM, Hudis CA. Estrogen and HER-2 receptor discor- dance between primary breast cancer and metastasis. Oncologist. 2010;15:1164-8.

21. Perez EA, Suman VJ, Davidson NE, Martino S, Kaufman PA, Lingle WL, et al. HER2 testing by local, central, and reference laboratories in specimens from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group N9831 intergroup adjuvant trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3032-8.

22. Shi ZD, Pang K, Wu ZX, Dong Y, Hao L, Qin JX, et al. Tumor cell plasticity in targeted therapy-induced resistance: mechanisms and new strategies. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8:113.

23. Beddowes E, Sammut SJ, Gao M, Caldas C. Predicting treatment resistance and relapse through circulating DNA. Breast. 2017;34:S31-5.

24. Di Cosimo S, De Marco C, Silvestri M, Busico A, Vingiani A, Pruneri G, et al. Can we define breast cancer HER2 status by liquid biopsy? Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2023;381:23-56.

25. Amir E, Clemons M, Purdie CA, Miller N, Quinlan P, Geddie W, et al. Tissue confirmation of disease recurrence in breast cancer patients: pooled analysis of multi-centre, multi-disciplinary prospective studies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2012;38:708-14.

26. Dieci MV, Barbieri E, Piacentini F, Ficarra G, Bettelli S, Dominici M, et al. Discordance in receptor status between primary and recurrent breast cancer has a prognostic impact: a single-institution analysis. Ann Oncol. 2013;24:101-8

27. Hoefnagel LD, Moelans CB, Meijer SL, van Slooten HJ, Wesseling P, Wesseling J, et al. Prognostic value of estrogen receptor α and progesterone receptor conversion in distant breast cancer metastases. Cancer. 2012;118:4929-35

28. Lindström LS, Karlsson E, Wilking UM, Johansson U, Hartman J, Lidbrink EK, et al. Clinically used breast cancer markers such as estrogen receptor, progesterone receptor, and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 are unstable throughout tumor progression. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2601-8

29. Niikura N, Liu J, Hayashi N, Mittendorf EA, Gong Y, Palla SL, et al. Loss of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) expression in metastatic sites of HER2-overexpressing primary breast tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:593-9

30. Bloom ND, Tobin EH, Schreibman B, Degenshein GA. The role of progesterone receptors in the management of advanced breast cancer. Cancer. 1980;45(12):2992-7

31. Bachmann C, Grischke EM, Staebler A, Schittenhelm J, Wallwiener D. Receptor change-clinicopathologic analysis of matched pairs of primary and cerebral metastatic breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2013;139:1909-16.

32. Shiino S, Ball G, Syed BM, Kurozumi S, Green AR, Tsuda H, et al. Prognostic significance of receptor expression discordance between primary and recurrent breast cancers: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2022;191(1):1-14.

33. Razavi P, Chang MT, Xu G, Bandlamudi C, Ross DS, Vasan N, et al. The Genomic Landscape of Endocrine-Resistant Advanced Breast Cancers. Cancer Cell 2018, 34:427-38.

34. Kunc M, Popęda M, Biernat W, Senkus E. Lost but Not Least-Novel Insights into Progesterone Receptor Loss in Estrogen Receptor-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(19):4755.

35. Zhan H, Antony VM, Tang H, Theriot J, Liang Y, Hui P, et al. PTEN inactivating mutations are associated with hormone receptor loss during breast cancer recurrence. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2025;211(2):441-7.

36. Wang Y, Zhang L, Che X, Li W, Liu Z, Jiang J. Roles of SIRT1/FoxO1/SREBP-1 in the development of progestin resistance in endometrial cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;298(5):961-9.

37. Jin X, Wei Y, Xu F, Zhao M, Dai K, Shen R, Yang S, Zhang N. SIRT1 promotes formation of breast cancer through modulating Akt activity. J Cancer. 2018;9(11):2012-23.

38. Moore RL, Faller DV. SIRT1 represses estrogen-signaling, ligand- independent ERα-mediated transcription, and cell proliferation in estrogen- responsive breast cells. J Endocrinol. 2013;216(3):273-85.

39. Witkiewicz AK, Knudsen ES. Retinoblastoma tumor suppressor pathway in breast cancer: prognosis, precision medicine, and therapeutic interventions. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:207.