Abstract

Despite the advance in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a proportion of patients suffer from residual symptoms such as pain and functional disability, even after they achieve inflammatory remission or low disease activity (LDA), which is defined as criteria of difficult-to-RA. This review summarizes current knowledge on frequency, possible pathogenesis, risk factors, and treatment options of remaining pain/functional disability among patients in inflammatory remission or LDA to highlight the complexity and difficulty in managing this condition. As an increased number of patients are achieving clinical remission, the residual symptoms will become one of the most significant unmet needs in the treatment of RA.

Keywords

Rheumatoid arthritis, Low disease activity, Inflammatory remission, Pain

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is one of the most common autoimmune diseases characterized by inflammatory arthritis that may lead to destruction of bone and cartilage. While the primary manifestation of RA is swollen and tender joints, it is often associated with multiple coexisting conditions such as fibromyalgia, fatigue, and malaise. Recent advancement in the treatment of RA realized remission of inflammation in many patients and even more, structural remission in some cases [1,2].

Despite this progress, therapies for RA still seem to fall short of achieving sufficient patients’ satisfaction levels. According to a web-based cross-sectional survey of RA patients who were enrolled in a patient research registry (Arthritis Power?) in the United States of America (USA), among adult RA patients with a history of ≥1 disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) failure who continue their current DMARD(s) for ≥6 months, only 26% of the patients were satisfied with the treatment defined as treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication (TSQM) global satisfaction score ≥8 [3]. TSQM consists of 11 questions and provides a validated score for effectiveness, side effects, convenience, and global satisfaction of the treatment [4]. Treatment satisfaction was measured using a cut-point of >8, which has been shown in past studies to be correlated with high medication adherence [5]. The patients who were unsatisfied with the current treatment were more likely to complain residual symptoms such as fatigue, sleep disturbance, and pain than those who were satisfied with the treatment. Another study showed increased pain without swollen joints led to a discrepancy toward worse patient perception than evaluator perception [6].

Such discrepancies between clinical indicators and subjective symptoms are observed even among patients who achieved remission [7] or low disease activity (LDA) [8,9] according to clinical indicators. Clinical remission is defined as Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) ≤3.3, Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) ≤2.2 [10,11] or fulfilling Boolean-based definition [12]. LDA is defined as Disease Activity Score (DAS) <3.2 [13], 3.3 < SDAI ≤11, and 2.2 < CDAI ≤10 [10,11].

In a multicenter observational study in Japan, among 464 RA patients in SDAI remission or LDA, 35% showed moderate or high disease activity (M/HDA) by patient reported outcome (PRO) measured by RAPID3 [8]. Another study targeting 93 RA patients in Italy showed that about one fourth of patients in LDA and up to one fifth of patients in remission had residual functional impairment with a Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) >0.5 [9]. A systematic review found that residual symptoms are observed in some patients despite their achieving LDA or remission, highlighting an unmet need in RA treatment [14].

This review summarizes the current understanding of residual pain and functional disability among RA patients who achieved clinical remission or LDA to highlight the importance and complexity of this unmet need.

Functional Disability and Pain among Patients Who Achieved LDA

Residual pain

Frequency in residual pain in patients with remission or LDA: Residual pain is not rare even among RA patients who achieved remission or LDA indicated by clinical indicators such as CDAI and DAS-28 [15].

Previous researches reported that the frequency of residual pain among the patients with LDA is 12.5 - 60% [16,17]. A multi-center study in Belgium targeting early RA patients revealed that about a fifth of the patients who achieved clinical remission, defined by DAS-28CRP (<2.6) complained fatigue or pain after a year of the treatment [18]. In another study, 29% of early RA patients who exhibit a good response according to the definition by the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) [19]. As a result, pain levels remained significantly higher than that of healthy controls even among patients who achieved clinical remission [20].

The incidence of residual pain in patients in remission or LDA varies depending on the definition used. A study that measured clinical remission by DAS28-CRP (<2.6) reported 11.8% of the patients who achieved the remission showed MD-HAQ pain ≥4 (of 10) [16]. However, the same researcher reported that none of the patients who achieved remission by American College of Rheumatology (ACR)/EULAR Boolean criteria [≤1 swollen joint; ≤1 tender joint; CRP ≤1 mg/dL, and patient global assessment score ≤1 (of 10)] showed residual pain [16]. Another study reported that 5% of those in clinical remission according to the ACR/EULAR Boolean criteria showed pain Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) ≥30 mm [21].

Our multi-center inception cohort study targeted RA patients who initiated biological/targeted-synthetic disease modifying antirheumatic drug (b/tsDMARD) [22] also showed that among those who achieved clinical LDA by CDAI (≤ 10) within 6 months, only 38% showed significant reduction in pain VAS (≥ 40 mm). Ad-hoc analysis using the same database revealed that among those who achieved clinical remission (CDAI ≤2.8), proportion of pain VAS remission (≤30 mm) [23] was limited to 74%. In addition, among the patients who exhibited pain VAS ≥40 mm at the start of the treatment, 19% failed to show significant pain VAS reduction (≥40 mm). These results suggest about 20~25% of the patients in clinical remission still exhibit some residual pain (unpublished data).

Possible pathogenesis of residual pain: Mechanisms of pain in RA are complex and multifactorial, including inflammation, peripheral and central pain processing, and structural change within the joint [24-26]. Therefore, residual pain after achieving LDA or remission is closely related, but not fully dependent on residual inflammation. An analysis of an early RA cohort showed 64% of participants at the time of their first pain flare [worsening ≥4.8 points of non-normed 36-item short form of the Medical Outcome Study Questionnaire- body pain (SF36-BP) between consecutive measurements] did not concurrently fulfil criteria for a DAS28 flare (an increase in DAS28 ≥1.2; or an increase ≥0.6 if the first of the paired visits had DAS28 ≤3.2 between consecutive study visits) [27]. Other researchers reported the presence of histopathological synovitis in RA patients with remission was not associated with a higher pain VAS [28].

Pain without apparent synovitis is partly caused by direct interaction between proinflammatory cytokines with nociceptors like Aδ and C fibers. Cytokines like tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1β, chemokine, nerve growth factor and prostaglandin are reported to reduce the threshold of nociceptive neurons to the stimulation and thus cause chronic pain [29,30]. Other cytokines, including interferon (IFN)-γ, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IL-15, IL-17, IL-18 positively mediate pain through the Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK/STAT) pathway, while IL-4, IL-10 act as anti-nociceptive cytokine [31]. Cytokines also act directly on the central nerve system (CNS). Recent findings suggest that proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6, IFN-γ, IL-1β, TNF-α affect astrocytes and CNS-associated myeloid cells and ultimately cause neuroplastic pains [31-33].

In addition to inflammatory pain, RA patients sometimes show neuropathic pain (NP). NP often presents as secondary symptoms as a result of long-term or intensive inflammation, but it also occurs without inflammation or joint destruction [34], which is observed in about 20% of RA patient [35]. The causes of such NP include entrapment neuropathy (e.g. carpal canal syndrome), spinal cord compression (e.g. cervical spine disorders due to atlantoaxial dislocation), peripheral cord neuropathy (e.g. amyloidosis), and small-fiber neuropathy (e.g. neuropathy in Sjögren syndrome) [36].

On top of all that, nociplastic pain, hypersensitivity of neurons, is now attracting attention of physicians. Nociplastic pain is recently defined as ‘pain that arises from altered nociception despite no clear evidence of actual or threatened tissue damage causing the activation of peripheral nociceptors or evidence for disease or lesion of the somatosensory system causing the pain’ [37]. Although the precise pathology is still to be elucidated, such pain is related to a variety of comorbidities like fibromyalgia, osteoarthritis, postoperative pain, and visceral pain hypersensitivity disorder [36].

Risk factors of residual pain: There are limited reports that describe direct risk factors of residual pain. In a 1-year follow-up of RA patients who achieved DAS-28 remission, higher Multi-Dimensional HAQ (MDHAQ) at 1 year was associated with patient global assessment, MDHAQ function, MDHAQ fatigue, MDHAQ sleep, and arthritis self-efficacy [16]. Another study targeting early RA patients reported higher HAQ at baseline is associated with remaining pain in spite of a EULAR good response [19]. Comparison of RA patients with healthy controls identified several factors that are associated with a higher level of pain in RA, which include older age, longer disease duration, female sex, higher heat distribution index (HDI), continent (highest in Africa, lowest in Asia), and ethnicity (highest in native Americans and lowest in Asians), higher fatigue, poorer function, psychiatric comorbidity, basic multimorbidity, patients global physical and mental health [20]. Fibromyalgia among early RA patients were associated with pain at baseline and poor mental health [38].

Our previous study [22] identified age ≥80 years old compared with 20-29 years old, past history of fracture, failure of ≥2 classes of b/tsDMARDs, use of glucocorticoid, higher pain VAS and lower HAQ-disability index (HAQ-DI) at baseline as risk factors of less improvement in pain VAS within 6 months of the treatment, though this does not directly show VAS remission.

Interestingly, positivity of anti-citrullinated peptide antibody (ACPA) and rheumatoid factor (RF) seem to be a beneficial factor for fibromyalgia [38] and residual pain [22]. One possibility is that seropositive patients might be diagnosed as RA earlier than seronegative ones and thus more likely to receive intensive treatment in the early stage of the disease. However, further research is required to identify the underlying causes.

Treatments of residual pain: As proinflammatory cytokines directly act on peripheral and central nerves, direct inhibition of these cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6 is expected to reduce nociplastic pains [32,39-41]. Especially, blocking IL-6 and JAK/STAT pathway is a promising treatment option. A recent study showed the effectiveness of anti-IL-6 antibody on disproportional pain [32] and unacceptable pain [39,40] among RA patients. Another study showed effectiveness of JAK inhibitor on residual pain of RA patients who achieved LDA [41]. Our study [22] also showed the use of JAK inhibitor significantly associated with reduction in pain VAS compared with TNF inhibitors. Even so, mechanisms of pain modulation are not sufficiently elucidated, and it is not clear whether it is reasonable to switch DMARDs of patients in remission just because of residual pain [42]. The current findings of residual pain are summarized in (Table 1).

|

Aspects |

Findings |

|

|

Frequency |

Literature review |

Ad-hoc analysis of our inception cohort |

|

Among those who achieved clinical remission (CDAI ≤2.8), 20-25% still exhibit some residual pain |

|

|

Pathogenesis |

|

|

|

Risk factors |

|

|

|

Possible treatment options |

Blocking proinflammatory cytokines, especially IL-6 and JAK/STAT pathway |

|

|

DAS: Disease Activity Score; RA: Rheumatoid Arthritis; EULAR: European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology; ACR: American College of Rheumatology; CDAI: Clinical Disease Activity Index; HAQ: Health Assessment Questionnaire; IL: Interleukin; JAK/STAT: Janus Kinase/Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription |

||

Functional disability

Frequency of functional disability in patients with remission or LDA: There is an accumulating evidence on the discrepancy between inflammatory remission or LDA either by clinical indicators [9] or ultrasonography [43] and functional improvement. Similar to residual pain, the incidence of functional disability in patients in remission or LDA varies depending on the definition used. A study found that 3% of the patients who achieved Boolean remission showed modified HAQ (mHAQ) >0.5 [21], while another study using SDAI reported 15% of the patients who achieved remission or LDA were categorized as moderate disease activity (MDA) or high disease activity (HDA) by Routine Assessment of Patient Index Data 3 (RAPID3) [8]. The proportion of functional disability increases with age, and thus a study targeting elderly RA patients showed 18% of patients at the age of ≥75 year old were HAQ >0.5 despite inflammatory remission by CDAI [44].

Even with this evidence, quantitative studies of functional disability are still lacking. A systematic review of [15] identified 34 articles that measured versions of HAQ, but few showed quantitative data on the frequency.

Our inception cohort of b/ts DMARD [22] revealed that 51% of the patients who achieved remission or LDA by CDAI within 6 months failed to achieve HAQ-DI normalization (<0.5). We conducted ad-hoc analyses and found that among 635 patients who achieved remission within 6 months, 139 (22%) did not achieve HAQ normalization. As HAQ normalization is dependent on baseline HAQ, we further analyzed the degree of HAQ improvement. Among the patients with HAQ >0.22 at baseline, 19% did not show significant improvement in HAQ-DI (by >0.22). Even more, 2.7% showed a significant increase (by >0.22) in HAQ within the period (unpublished data).

Possible pathogenesis of residual functional disability: Although it is well-known that the proportion of functional disability among RA patients is higher than the healthy population [45], there is a paucity of literature that overviews its pathogenesis. Major causes of functional disability in the general elderly population are orthopedic diseases, dementia, and stroke [46], all of which are reported to be induced by RA. Orthopedic conditions are common in RA patients. Sometimes joint destruction and deformity cause a permanent reduction in HAQ (structural HAQ). Such impairment is observed even within a year from the onset [47].

Different from structural HAQ, stroke and cognitive impairment lead to reduction in HAQ without structural damage (functional HAQ). Although dementia risk in RA patients is still ambivalent [48], there are some evidence that inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α cause cognitive deficit via synaptic plasticity, neurogenesis, and neuromodulation [49]. In addition, risks of cardiovascular diseases in RA patients are reported to be higher than healthy controls [50], partly due to chronic inflammation.

In addition to these common causes of functional disability, RA patients exhibit a variety of comorbidities associated with functional HAQ, including fatigue, malaise, depression, and sarcopenia [51]. Some cytokines related to the pathogenesis of RA are reported to be linked to symptoms of encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome (ME/CFS) [52].

One mechanism that is common in a variety of fatigue, pain, and depression is stimulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, which changes metabolism and catabolism of muscle and adipose tissues and reduces in physical activities as well [53]. The HPA axis seems to exert an ambivalent effect on fatigue. Stimulation of HPA axis may increase fatigue by upregulating catabolism and inflammation, while its hypofunction may also lead to fatigue via adrenal dysfunction [51].

Risk factors for functional disabilities: Joint damage, especially among elderly RA patients [45], is a major risk factor of functional disability in RA patients in general. It accounts for about 20% of HAQ scores among recent-onset RA patients [54]. Long-term high HAQ-DI is also associated with baseline or 1-year HAQ score, older age, female sex, disease activity, RF/ACPA positivity, co-morbidities, low education and low socio-economic status (SES) [55,56], patient’s global health, physician’s global assessment, depression score [57], myalgia, and fatigue [58]. Interestingly, disability index progress more slowly when patients were treated by a rheumatologist regularly than intermittently [59], presumably due to more intensive use of second-line antirheumatic medications, and more frequent joint surgeries when appropriate.

Nevertheless, risk factors of functional disability among patients in inflammatory remission or LDA are still to be elucidated. Komiya et al. targeted elderly RA patients (55-84 years old) with LDA and identified higher age, higher SDAI at baseline, concomitant use of glucocorticoid, nonuse of MTX as risk factors for HAQ >0.5 within 1-year observation period [44]. Another research on early RA patients found that patients in the “low inflammation - high HAQ” group identified by latent class analysis were on average older, were more often female, had more comorbidity and had more severe pain, fatigue, anxiety and depressive symptoms at baseline compared with patients in the “low inflammation - low HAQ” group [60]. Our previous research [22] found that longer disease duration, female sex, higher HAQ-DI at baseline, failure of ≥2 classes of b/tsDMARDs, and use of glucocorticoids are associated with less likelihood of the HAQ-DI normalization, while JAK inhibitor compared with TNF-α related to more likelihood of the normalization.

As functional disabilities are multifaceted and interrelated conditions, there might be a need to identify risk factors for each different condition.

Treatment of functional disability: As functional disability and pain are closely related, the treatments of residual pain listed in Table 1 will be effective for functional disability as well. Moreover, given that inflammatory cytokines cause not only pain, but also fatigue [51], depression [61], and cognitive disfunction [49], anti-cytokine strategies may ameliorate residual symptoms closely related to functional disability independent of inflammation.

Our research [22] showed that JAK inhibitors use was associated with more frequent HAQ-DI normalization (<0.5) compared with TNF inhibitors use among patients in CDAI remission or LDA, which is consistent with a systematic review that showed advantage of JAK inhibitors to other bDMARDs in the improvement of SF-36 physical component score and functional assessment of chronic illness therapy – fatigue (FACIT-F) [62]. This preferable outcome of JAK inhibitors may partly reflect the rapid-acting nature [63-65] of these agents as well as direct effect. Given that long-lasting pain may cause decline in physical activity and thus worsen functional disability, and that patients prefer rapid onset of action of their treatment [66], time-to-response is an important aspect to be considered in the treatment choice.

One remaining question is whether to start or switch b/tsDMARD when patients achieved inflammatory remission but not satisfied with the treatment. As relief of symptom are leading treatment expectation of RA patients [66], it would be reasonable to switch DMARD to achieve treat-to-target (T2T). Even so, physicians may hesitate to escalate treatment just because of symptoms, from concern about adverse events such as malignancies. Therefore, further research about the benefit of treatment modifications among patients with high HAQ but low inflammation is required.

As well as modifications of b/tsDMARDs, de-escalation of glucocorticoid might be another treatment option for functional disfunction. Glucocorticoid increases risks of osteoporosis in a dose-dependent manner [67] and reduction of the agent improved bone metabolism independent of disease activity [68]. In addition, long-term use of glucocorticoid suppresses HPA axis and cause adrenal atrophy, which can exacerbate fatigue and malaise among RA patients [51]. For these reasons, early reduction or cessation of glucocorticoid will be effective on functional HAQ among patients who achieved LDA.

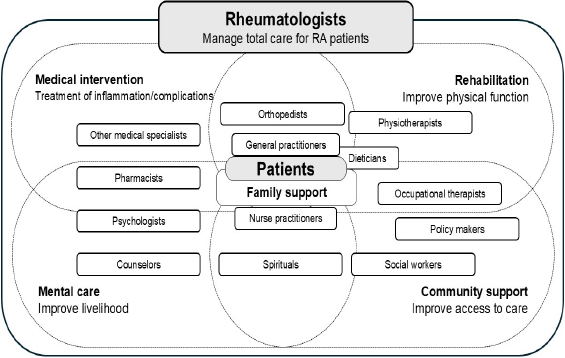

In addition to the choice of drugs, other pharmacological, nutritional, psychological, and behavioral intervention is important to treat non-inflammatory comorbidities. Physical exercise [69,70], intake of vitamin D and omega-3 [70] as well as social support [71] are effective to improve physical activities of RA patients with depressive status and fatigue. For patients with fibromyalgia, anti-depressant and naltrexone, physiotherapy like acupuncture, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) or direct current stimulation (DCS), education, and other physical and psychological therapies should be considered [72]. Nevertheless, such an integrated way of care requires time and cost and may lead to an “RA paradox”, in which specialized care may compete with a general plan of care [73]. As intervention on depression and fatigue is also affected by cultural sensitivity and social support [69,71,74], the management may require a holistic approach involving a variety of stakeholders in the community (Figure 1).

Figure 1. An example of patient-centered multidisciplinary approach for residual symptoms.

The current findings of functional disabilities among RA patients in remission or LDA are summarized in (Table 2).

|

Aspects |

Findings |

|

|

Frequency |

Literature review |

Ad-hoc analysis of our inception cohort |

|

Among those with clinical remission (CDAI ≤2.8), about 20% did not achieve HAQ-DI improvement (by ≥0.22) |

|

|

Pathogenesis |

|

|

|

Risk factors |

|

|

|

Possible treatment options |

|

|

|

RA: Rheumatoid Arthritis; mHAQ: Minimal Health Assessment Questionnaire; SDAI: Simplified Disease Activity Index; LDA: Low Disease Activity; MDA: Moderate Disease Activity; HDA: High Disease Activity; CDAI: Clinical Disease Activity Index; HAQ-DI; HAQ-Disability Index; IL: Interleukin; TNF: Tumor Necrosis Factor; HPA axis: Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal axis; b/tsDMARD: biological/Targeted-Synthetic Disease Modifying Antirheumatic Drug; JAK: Janus Kinase; rTMS: Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation; DCS: Direct Current Stimulation |

||

Discussion

In 2022, EULAR and ACR defined difficult-to-treat RA (D2T RA) as a group of patients who remain symptomatic despite recommended treatment changes [75]. D2T RA includes heterogeneous conditions that are categorized into 3 main criteria: 1) Treatment failure history; 2) characterization of active/symptomatic disease, and 3) clinical perceptions. Among these definitions, Criteria 3, described as “The management of signs and/or symptoms is perceived as problematic by the rheumatologist and/or the patient”, weigh much on subjective complaint of the patients and thus lacks tools of objective evaluation. Recent advancement in DMARDs remarkably decreases D2T RA patients of criteria 1 and 2. On the other hand, D2T RA of criteria 3 seems to become a major unmet need in RA patients who achieved inflammatory remission or LDA.

Ageing of RA patients and increased importance in residual symptoms in Japan

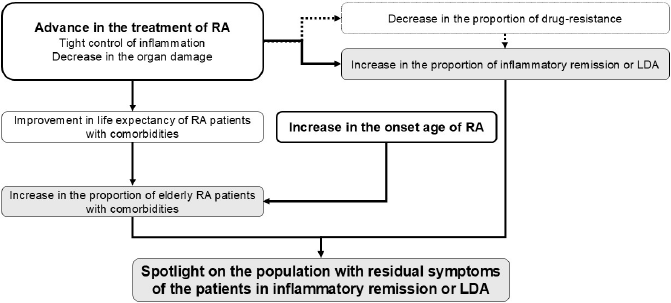

The needs in the management of such residual symptoms will increase with the ageing of the population. Asian countries, especially Japan, are facing rapid ageing of the population. Moreover, the proportion of the patients with RA is aging far more rapidly than the general population for two reasons. First is improvement of treatment outcome due to the advancement of DMARDs, which slowed down organ dysfunction such as amyloidosis and joint destruction. As a result, patients with comorbidities can live to advanced age. Second, the age at onset is also increasing from unknown reasons [76]. In the 1960s, the proportion of elderly-onset RA in Japan was less than 10% and increased to more than 20% in the late 1980s [77], and >50% in 2012 [76]. Even among those who receive b/tsDMARDs, the age at the initiation or switching of b/tsDMARDs increased from 51.9 years in 2003 to 64.3 years in 2023. Partly due to this aging population, an increasing number of RA patients have comorbidity, which may affect residual symptoms. Our registry data revealed that the prevalence of comorbidities of the patients who receive b/tsDMARDs such as chronic kidney disease, lung disease, history of fragility fractures, history of pneumonia, history of malignancy, major adverse cardiovascular events, and thrombosis increased by 2-5 times in these two decades (unpublished data), highlighting the increasing complexity of the management of RA. Because of the increase in elderly RA patients and decrease in the proportion of drug-resistant patients, management of residual symptoms of the patient who achieved inflammatory remission or LDA is becoming increasingly important (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Scheme of the increased importance in the management of residual symptom of RA patients who achieved remission and low disease activity (LDA).

Challenges in the management of residual symptoms

Recent studies have revealed that worse functional disability is associated with cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [78], joint damage, work disability [55], and employment rate [58]. However, there still exist several challenges to overcome in the management of the disability among patients in inflammatory remission or LDA. First, there is lack of assessment tools and there are no validated consensus tools to evaluate and monitor residual symptoms [51]. Lack of either imaging or laboratory tests make an impartial assessment of residual symptoms difficult. Currently, some outcome indicators such as subjective pain, HAQ-DI, Euro QoL-5 Dimensional questionnaire (EQ-5D), and SF-36 are used, but they cannot distinguish non-inflammatory symptoms from inflammatory ones. To establish effective treatment strategies, tools that can discern whether the symptoms arise from inflammation, structural damages, nociceptive and/or nociplastic mechanisms, or psychological factors.

Second, research methods on residual symptoms are not standardized, which makes it difficult to synthesize evidence generated all over the world. We may need to establish global consensus in the timing of evaluation, collection of clinical variables such as comorbidity and SES, inclusion criteria of the patients, and outcome measurement.

Third, treatment options for residual symptoms of patients in remission or LDA. Intervention on depressive status may improve disease management and daily functioning of the patients [69], but the size of the impact is still to be elucidated. Effective intervention for fatigue is still an unmet need for RA patients [70]. Further research on non-drug treatment including self-management, rehabilitation, and physiotherapy is also required.

Conclusion

Residual symptoms of patients in remission or LDA are becoming a major unmet need in RA treatment. Elucidating molecular mechanisms of each symptom such as pain, fatigue, sleep disorder, and malaise, and standardized methods that enable synthesis of evidence are required to overcome the dearth of evidence in this field. Rheumatologists should involve a variety of stakeholders in their community to improve patients’ well-being and functioning as a whole.

References

2. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, McInnes IB. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2016 Oct 22;388(10055):2023-38.

3. Radawski C, Genovese MC, Hauber B, Nowell WB, Hollis K, Gaich CL, et al. Patient Perceptions of Unmet Medical Need in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Cross-Sectional Survey in the USA. Rheumatol Ther. 2019 Sep;6(3):461-71.

4. Atkinson MJ, Kumar R, Cappelleri JC, Hass SL. Hierarchical construct validity of the treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication (TSQM version II) among outpatient pharmacy consumers. Value Health. 2005 Nov-Dec;8 Suppl 1:S9-S24.

5. Reynolds K, Viswanathan HN, O'Malley CD, Muntner P, Harrison TN, Cheetham TC, et al. Psychometric properties of the Osteoporosis-specific Morisky Medication Adherence Scale in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis newly treated with bisphosphonates. Ann Pharmacother. 2012 May;46(5):659-70.

6. Studenic P, Radner H, Smolen JS, Aletaha D. Discrepancies between patients and physicians in their perceptions of rheumatoid arthritis disease activity. Arthritis Rheum. 2012 Sep;64(9):2814-23.

7. Wolfe F, Boers M, Felson D, Michaud K, Wells GA. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis: physician and patient perspectives. J Rheumatol. 2009 May;36(5):930-3.

8. Suzuki M, Asai S, Ohashi Y, Sobue Y, Ishikawa H, Takahashi N, et al. Factors associated with discrepancies in disease activity as assessed by SDAI and RAPID3 in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Data from a multicenter observational study (T-FLAG). Mod Rheumatol. 2024 May 10:roae040.

9. Perrotta FM, De Socio A, Scriffignano S, Lubrano E. Residual disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with subcutaneous biologic drugs that achieved remission or low disease activity: a longitudinal observational study. Clin Rheumatol. 2018 Jun;37(6):1449-55.

10. Aletaha D, Smolen J. The Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI) and the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI): a review of their usefulness and validity in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005 Sep-Oct;23(5 Suppl 39):S100-8.

11. Anderson J, Caplan L, Yazdany J, Robbins ML, Neogi T, Michaud K, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis disease activity measures: American College of Rheumatology recommendations for use in clinical practice. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 May;64(5):640-7.

12. Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, Zhang B, van Tuyl LH, Funovits J, et al; American College of Rheumatology; European League Against Rheumatism. American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Mar;63(3):573-86.

13. Ometto F, Botsios C, Raffeiner B, Sfriso P, Bernardi L, Todesco S, et al. Methods used to assess remission and low disease activity in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev. 2010 Jan;9(3):161-4.

14. Michaud K, Pope J, van de Laar M, Curtis JR, Kannowski C, Mitchell S, et al. Systematic Literature Review of Residual Symptoms and an Unmet Need in Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021 Nov;73(11):1606-16.

15. Ishida M, Kuroiwa Y, Yoshida E, Sato M, Krupa D, Henry N, et al. Residual symptoms and disease burden among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in remission or low disease activity: a systematic literature review. Mod Rheumatol. 2018 Sep;28(5):789-99.

16. Lee YC, Cui J, Lu B, Frits ML, Iannaccone CK, Shadick NA, et al. Pain persists in DAS28 rheumatoid arthritis remission but not in ACR/EULAR remission: a longitudinal observational study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011 Jun 8;13(3):R83.

17. McWilliams DF, Walsh DA. Factors predicting pain and early discontinuation of tumour necrosis factor-α-inhibitors in people with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the British society for rheumatology biologics register. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016 Aug 12;17:337.

18. Van der Elst K, Verschueren P, De Cock D, De Groef A, Stouten V, Pazmino S, et al. One in five patients with rapidly and persistently controlled early rheumatoid arthritis report poor well-being after 1 year of treatment. RMD Open. 2020 Apr;6(1):e001146.

19. Altawil R, Saevarsdottir S, Wedrén S, Alfredsson L, Klareskog L, Lampa J. Remaining Pain in Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients Treated With Methotrexate. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2016 Aug;68(8):1061-8.

20. Hmamouchi I, Ziade N, Salameh B, Moussallem M, Kadam E, Tan AL, et al. POS0333 DETERMINANTS OF RESIDUAL PAIN IN PATIENTS WITH AUTOIMMUNE RHEUMATIC DISEASES IN REMISSION: A LATENT CLASS ANALYSIS FROM THE COVAD GLOBAL SURVEY. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2024;83(Suppl 1):323.

21. Navarro-Millán I, Chen L, Greenberg JD, Pappas DA, Curtis JR. Predictors and persistence of new-onset clinical remission in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Oct;43(2):137-43.

22. Ochi S, Sonomoto K, Nakayamada S, Tanaka Y. Predictors of functional improvement and pain reduction in rheumatoid arthritis patients who achieved low disease activity with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: a retrospective study of the FIRST Registry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2024 Jul 26;26(1):140.

23. Amirdelfan K, Gliner BE, Kapural L, Sitzman BT, Vallejo R, Yu C, et al. A proposed definition of remission from chronic pain, based on retrospective evaluation of 24-month outcomes with spinal cord stimulation. Postgrad Med. 2019 May;131(4):278-86.

24. Walsh DA, McWilliams DF. Mechanisms, impact and management of pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2014 Oct;10(10):581-92.

25. McWilliams DF, Walsh DA. Pain mechanisms in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2017 Sep-Oct;35 Suppl 107(5):94-101.

26. Sebba A. Pain: A Review of Interleukin-6 and Its Roles in the Pain of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Open Access Rheumatol. 2021 Mar 5;13:31-43.

27. McWilliams DF, Rahman S, James RJE, Ferguson E, Kiely PDW, Young A, et al. Disease activity flares and pain flares in an early rheumatoid arthritis inception cohort; characteristics, antecedents and sequelae. BMC Rheumatol. 2019 Nov 18;3:49.

28. Perniola S, Petricca L, Gessi M, Gigante MR, Calabretta M, Bruno D, et al. POS1344 CLINICAL AND HISTOLOGICAL FEATURES OF RESIDUAL PAIN IN RHEUMATOID ARTHRITIS REMISSION STATUS. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2023;82(Suppl 1):1023.

29. Motyl G, Krupka WM, Maślińska M. The problem of residual pain in the assessment of rheumatoid arthritis activity. Reumatologia. 2024;62(3):176-86.

30. Schaible HG. Nociceptive neurons detect cytokines in arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(5):470.

31. Simon LS, Taylor PC, Choy EH, Sebba A, Quebe A, Knopp KL, et al. The Jak/STAT pathway: A focus on pain in rheumatoid arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2021 Feb;51(1):278-84.

32. Choy E, Bykerk V, Lee YC, van Hoogstraten H, Ford K, Praestgaard A, et al. Disproportionate articular pain is a frequent phenomenon in rheumatoid arthritis and responds to treatment with sarilumab. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2023 Jul 5;62(7):2386-93.

33. Süß P, Rothe T, Hoffmann A, Schlachetzki JCM, Winkler J. The Joint-Brain Axis: Insights From Rheumatoid Arthritis on the Crosstalk Between Chronic Peripheral Inflammation and the Brain. Front Immunol. 2020 Dec 10;11:612104.

34. Ito S, Kobayashi D, Murasawa A, Narita I, Nakazono K. An Analysis of the Neuropathic Pain Components in Rheumatoid Arthritis Patients. Intern Med. 2018 Feb 15;57(4):479-85.

35. Noda K, Tajima M, Oto Y, Saitou M, Yoshiga M, Otani K, et al. How do neuropathic pain-like symptoms affect health-related quality of life among patients with rheumatoid arthritis?: A comparison of multiple pain-related parameters. Mod Rheumatol. 2020 Sep;30(5):828-834.

36. Bailly F, Cantagrel A, Bertin P, Perrot S, Thomas T, Lansaman T, et al. Part of pain labelled neuropathic in rheumatic disease might be rather nociplastic. RMD Open. 2020 Sep;6(2):e001326.

37. Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, Finnerup NB, Flor H, Gibson S, et al. The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020 Sep 1;161(9):1976-82.

38. Lee YC, Lu B, Boire G, Haraoui BP, Hitchon CA, Pope JE, et al. Incidence and predictors of secondary fibromyalgia in an early arthritis cohort. Ann Rheum Dis. 2013 Jun;72(6):949-54.

39. Tanaka Y, Takahashi T, van Hoogstraten H, Kato N, Kameda H. Effect of sarilumab on unacceptable pain and inflammation control in Japanese patients with moderately-to-severely active rheumatoid arthritis: Post hoc analysis of a Phase III study (KAKEHASI). Mod Rheumatol. 2024 Jul 6;34(4):670-7.

40. Tanaka Y, Takahashi T, van Hoogstraten H, Kato N, Kameda H. The effects of sarilumab as monotherapy and in combination with non-methotrexate disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs on unacceptable pain in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a post-hoc analysis of the HARUKA phase 3 study. Mod Rheumatol. 2024 Jul 29:roae055.

41. De Stefano L, Bozzalla Cassione E, Bottazzi F, Marazzi E, Maggiore F, Morandi V, et al. Janus kinase inhibitors effectively improve pain across different disease activity states in rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Emerg Med. 2023 Sep;18(6):1733-40.

42. Berghea F, Berghea CE, Zaharia D, Trandafir AI, Nita EC, Vlad VM. Residual Pain in the Context of Selecting and Switching Biologic Therapy in Inflammatory Rheumatic Diseases. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021 Aug 17;8:712645.

43. van der Ven M, Kuijper TM, Gerards AH, Tchetverikov I, Weel AE, van Zeben J, et al. No clear association between ultrasound remission and health status in rheumatoid arthritis patients in clinical remission. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017 Aug 1;56(8):1276-81.

44. Komiya Y, Sugihara T, Hirano F, Matsumoto T, Kamiya M, Sasaki H, et al. Factors associated with impaired physical function in elderly rheumatoid arthritis patients who had achieved low disease activity. Mod Rheumatol. 2023 Dec 22;34(1):60-7.

45. Myasoedova E, Davis JM 3rd, Achenbach SJ, Matteson EL, Crowson CS. Trends in Prevalence of Functional Disability in Rheumatoid Arthritis Compared With the General Population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019 Jun;94(6):1035-9.

46. Yoshida D, Ninomiya T, Doi Y, Hata J, Fukuhara M, Ikeda F, et al. Prevalence and causes of functional disability in an elderly general population of Japanese: the Hisayama study. J Epidemiol. 2012;22(3):222-9.

47. van der Heijde DM. Joint erosions and patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Br J Rheumatol. 1995 Nov;34 Suppl 2:74-8.

48. Sharma SR, Chen Y. Rheumatoid Arthritis and Cognitive Impairment or Dementia: An Updated Review of Epidemiological Data. J Alzheimers Dis. 2023;95(3):769-83.

49. McAfoose J, Baune BT. Evidence for a cytokine model of cognitive function. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2009 Mar;33(3):355-66.

50. Weber BN, Giles JT, Liao KP. Shared inflammatory pathways of rheumatoid arthritis and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2023 Jul;19(7):417-28.

51. Tanaka Y, Ikeda K, Kaneko Y, Ishiguro N, Takeuchi T. Why does malaise/fatigue occur? Underlying mechanisms and potential relevance to treatments in rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2024 May;20(5):485-99.

52. Montoya JG, Holmes TH, Anderson JN, Maecker HT, Rosenberg-Hasson Y, Valencia IJ, et al. Cytokine signature associated with disease severity in chronic fatigue syndrome patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017 Aug 22;114(34):E7150-8.

53. Yang S, Chu S, Gao Y, Ai Q, Liu Y, Li X, et al. A Narrative Review of Cancer-Related Fatigue (CRF) and Its Possible Pathogenesis. Cells. 2019 Jul 18;8(7):738.

54. Wolfe F, Sharp JT. Radiographic outcome of recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis: a 19-year study of radiographic progression. Arthritis Rheum. 1998 Sep;41(9):1571-82.

55. Norton S, Fu B, Scott DL, Deighton C, Symmons DP, Wailoo AJ, et al. Health Assessment Questionnaire disability progression in early rheumatoid arthritis: systematic review and analysis of two inception cohorts. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014 Oct;44(2):131-44.

56. Scott DL, Pugner K, Kaarela K, Doyle DV, Woolf A, Holmes J, et al. The links between joint damage and disability in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000 Feb;39(2):122-32.

57. Hammad M, Eissa M, Dawa GA. Factors contributing to disability in rheumatoid arthritis patients: An Egyptian multicenter study. Reumatol Clin (Engl Ed). 2020 Mar-Apr;16(2 Pt 1):103-109.

58. Intriago M, Maldonado G, Guerrero R, Moreno M, Moreno L, Rios C. Functional Disability and Its Determinants in Ecuadorian Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Open Access Rheumatol. 2020 Jun 10;12:97-104.

59. Ward MM, Leigh JP, Fries JF. Progression of functional disability in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Associations with rheumatology subspecialty care. Arch Intern Med. 1993 Oct 11;153(19):2229-37.

60. Gwinnutt JM, Norton S, Hyrich KL, Lunt M, Combe B, Rincheval N, et al. Exploring the disparity between inflammation and disability in the 10-year outcomes of people with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2022 Nov 28;61(12):4687-701.

61. Nerurkar L, Siebert S, McInnes IB, Cavanagh J. Rheumatoid arthritis and depression: an inflammatory perspective. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Feb;6(2):164-173.

62. óth L, Juhász MF, Szabó L, Abada A, Kiss F, Hegyi P, et al. Janus Kinase Inhibitors Improve Disease Activity and Patient-Reported Outcomes in Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of 24,135 Patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 Jan 23;23(3):1246.

63. Wallenstein GV, Kanik KS, Wilkinson B, Cohen S, Cutolo M, Fleischmann RM, et al. Effects of the oral Janus kinase inhibitor tofacitinib on patient-reported outcomes in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis: results of two Phase 2 randomised controlled trials. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2016 May-Jun;34(3):430-42.

64. Ochi S, Sonomoto K, Nakayamada S, Tanaka Y. Preferable outcome of Janus kinase inhibitors for a group of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis patients: from the FIRST Registry. Arthritis Res Ther. 2022 Mar 1;24(1):61.

65. Coombs JH, Bloom BJ, Breedveld FC, Fletcher MP, Gruben D, Kremer JM, et al. Improved pain, physical functioning and health status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with CP-690,550, an orally active Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor: results from a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010 Feb;69(2):413-6.

66. Taylor PC, Ancuta C, Nagy O, de la Vega MC, Gordeev A, Janková R, et al. Treatment Satisfaction, Patient Preferences, and the Impact of Suboptimal Disease Control in a Large International Rheumatoid Arthritis Cohort: SENSE Study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2021 Feb 17;15:359-73.

67. Adami G, Saag KG. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis update. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2019 Jul;31(4):388-93.

68. Tada M, Inui K, Sugioka Y, Mamoto K, Okano T, Koike T, et al. Reducing glucocorticoid dosage improves serum osteocalcin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis-results from the TOMORROW study. Osteoporos Int. 2016 Feb;27(2):729-35.

69. Withers MH, Gonzalez LT, Karpouzas GA. Identification and Treatment Optimization of Comorbid Depression in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatol Ther. 2017 Dec;4(2):281-91.

70. Pope JE. Management of Fatigue in Rheumatoid Arthritis. RMD Open. 2020 May;6(1):e001084.

71. Xu N, Zhao S, Xue H, Fu W, Liu L, Zhang T, et al. Associations of perceived social support and positive psychological resources with fatigue symptom in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. PLoS One. 2017 Mar 14;12(3):e0173293.

72. Giorgi V, Sirotti S, Romano ME, Marotto D, Ablin JN, Salaffi F, et al. Fibromyalgia: one year in review 2022. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2022 Jun;40(6):1065-72.

73. Boyd T, Kavanaugh A. Clinical guidelines: Addressing comorbidities in systemic inflammatory disorders. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2015 Dec;11(12):689-91.

74. Withers M, Moran R, Nicassio P, Weisman MH, Karpouzas GA. Perspectives of vulnerable U.S Hispanics with rheumatoid arthritis on depression: awareness, barriers to disclosure, and treatment options. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2015 Apr;67(4):484-92.

75. Nagy G, Roodenrijs NMT, Welsing PM, Kedves M, Hamar A, van der Goes MC, et al. EULAR definition of difficult-to-treat rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021 Jan;80(1):31-5.

76. Kato E, Sawada T, Tahara K, Hayashi H, Tago M, Mori H, et al. The age at onset of rheumatoid arthritis is increasing in Japan: a nationwide database study. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017 Jul;20(7):839-45.

77. Imanaka T, Shichikawa K, Inoue K, Shimaoka Y, Takenaka Y, Wakitani S. Increase in age at onset of rheumatoid arthritis in Japan over a 30 year period. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997 May;56(5):313-6.

78. Farragher TM, Lunt M, Bunn DK, Silman AJ, Symmons DP. Early functional disability predicts both all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in people with inflammatory polyarthritis: results from the Norfolk Arthritis Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007 Apr;66(4):486-92.