Abstract

Purpose: To describe a case in which a large intraocular glass fragment was successfully retrieved using a basket device originally designed for kidney stone extraction.

Methods: Retrospective case report.

Case: A 17-year-old male presented four days after open globe repair following a motor vehicle accident with a large intravitreal glass fragment measuring 5 × 4 × 3.5 mm³. Surgical management included pars plana lensectomy and vitrectomy. A four-prong nephrolithiasis basket was ultimately successful in retrieving the thick, smooth-surfaced glass fragment after conventional instruments failed to achieve extraction.

Conclusion: Removal of large, smooth intraocular glass or spherical plastic foreign bodies presents a significant surgical challenge. A kidney stone basket device may serve as an effective alternative for the removal of bulky foreign bodies that are too large or slippery to be securely grasped with conventional forceps.

Keywords

Glass, Intraocular foreign body, IOFB, Motor vehicle accident, Ocular trauma, Open globe, Kidney stone basket, Nephrolith, Salivary stone basket

Introduction

Intraocular foreign bodies (IOFBs) are a major cause of visual impairment in adolescents and young adults and are associated with 18–41% of open globe injuries [1–4]. Motor vehicle accidents resulting in penetrating ocular trauma are commonly associated with windshield glass IOFBs, in up to 70% of cases [5,6].

Surgical removal of glass IOFBs can sometimes be particularly challenging. Their large size, jagged edges, and smooth surface characteristics make intravitreal manipulation difficult and increase the risk of iatrogenic retinal trauma [7–10]. In search of versatile IOFB removal techniques, we present a case of successful removal of a large glass IOFB using a stone extractor basket originally designed for kidney stone retrieved in the ureter.

Case Report

A 17-year-old male was referred to a retina specialist (NB) for management of a persistent glass IOFB four days after repair of an open globe injury sustained in a motor vehicle accident. Visual acuity in the affected right eye was light perception, with an intraocular pressure (IOP) of 15 mm Hg. Slit-lamp examination revealed a 6 mm corneal wound with intact sutures, diffuse corneal edema, a dense white cataract, and no view of the posterior segment.

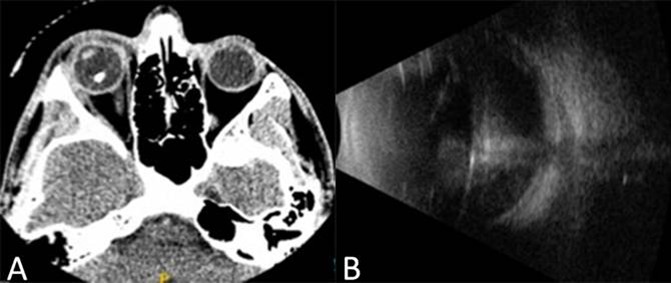

Computed tomography (CT) of the orbits revealed a 5 ´ 4 ´ 3.5 mm3 intravitreal radio-opaque foreign body (Figure 1A). B-scan ultrasonography demonstrated vitreous hemorrhage, an attached retina, and a foreign body with A-scan reflectivity consistent with glass (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. A. CT of the globe showing a radiopaque intraocular foreign body in the right eye. B. B-scan ultrasound of the right eye showing a non-metallic intraocular foreign body and associated vitreous hemorrhage.

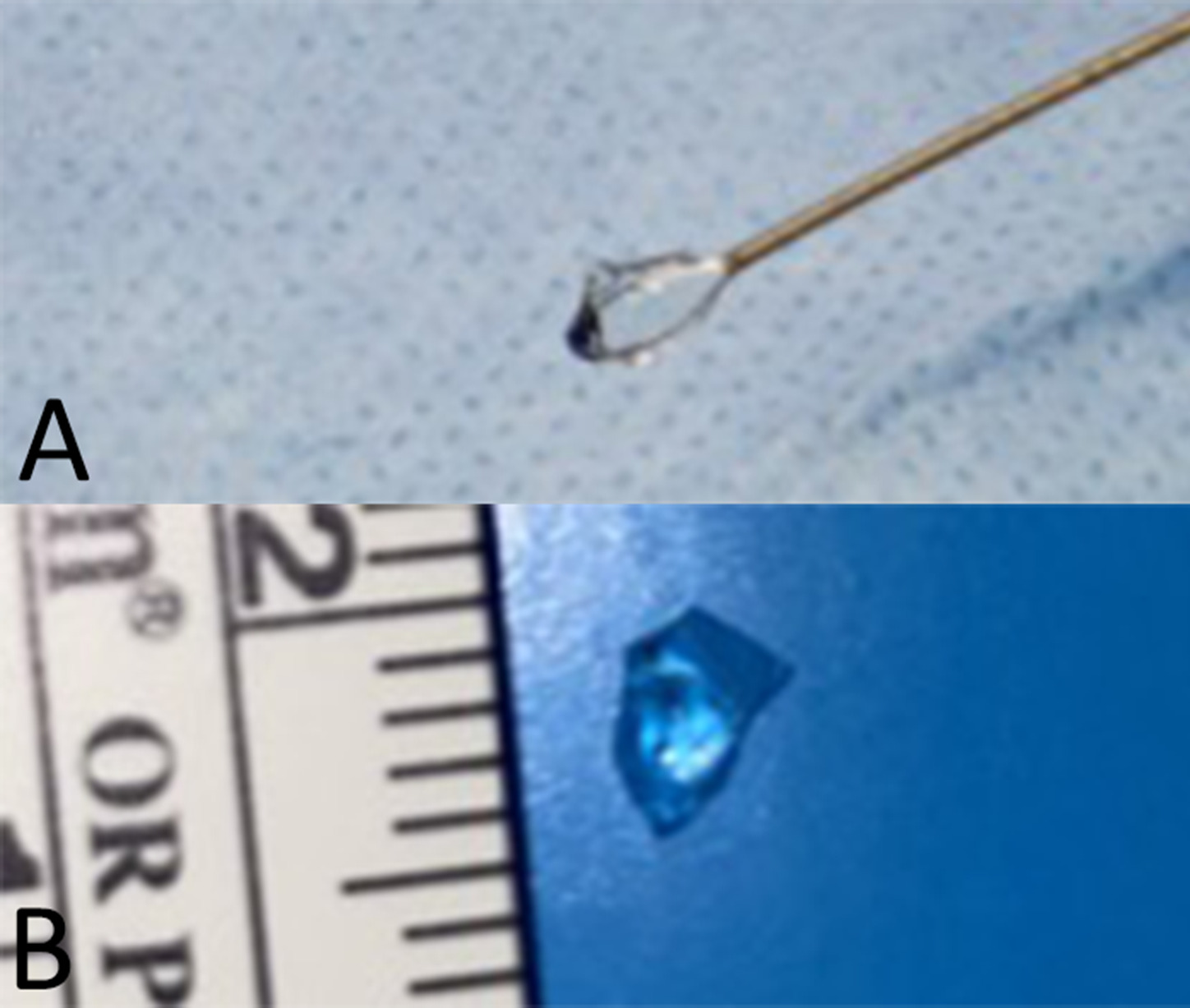

The patient underwent a complete 23-gauge pars plana vitrectomy with lensectomy. Intraoperatively, a large irregular thick glass IOFB with jagged edges was noted in the inferior vitreous cavity, along with vitreous hemorrhage, peripheral retinal tears and a shallow infero-temporal retinal detachment. The thick glass piece had a smooth surface and proved extremely slippery when grasped with conventional diamond-coated IOFB forceps. To overcome this limitation, retrieval of the IOFB was attempted with a four-wire Nitinol stone basket. The glass fragment was guided into the basket, after which the prongs were collapsed around it, securely enclosing the fragment and preventing slippage. The basket was then carefully removed through an enlarged 6 mm sclerotomy, with meticulous attention to avoid tugging of vitreous strands (Figures 2A and 2B). The sclerotomy was subsequently closed to its original size.

Figure 2. A. Tipless nitinol stone basket enclosing the extracted glass intraocular foreign body from the vitreous cavity, B. glass foreign body, measured 5 mm ´ 4 mm ´ 3.5 mm in size.

An air-fluid exchange was performed, followed by focal demarcation laser photocoagulation around the retinal tears and silicone oil tamponade was used. Silicone oil was removed four weeks later during a subsequent procedure. Two months following the surgery, best- corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/30. The patient later underwent anterior chamber intraocular lens (ACIOL) implantation by a cornea specialist at four months, achieving a BCVA of 20/25 two months postoperatively.

Discussion

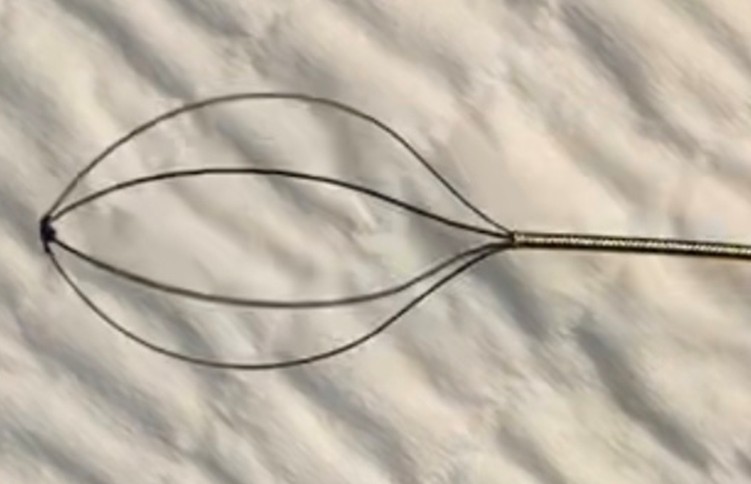

Glass IOFBs present multiple management challenges. First, their relative radiolucency on plain radiography and CT imaging can make detection difficult. Second, surgical removal from the posterior segment can be formidable; the combination of jagged thick edges and smooth surfaces makes these fragments difficult to grab and manipulate using conventional IOFB forceps [6,8,11,12]. In some cases, glass IOFBs are intentionally left in the vitreous cavity if the glass is inert and carries a low risk of endophthalmitis [13]. Various specialized tools—including claw-like forceps, active aspiration silicone tips, snares, and lassos have been described for the removal of large nonferromagnetic foreign bodies [11,14–17]. Our case demonstrates the successful use of a SkyLiteTM Tipless Nitinol stone basket (CR Bard, Inc Covington, GA), a device originally designed for kidney stone extraction (Figure 3), to remove an IOFB.

Figure 3. Tipless nitinol nephrolith (kidney stone) basket 0.6mm tool, used to remove the thick glass fragment discussed in this case.

The basket is available in multiple sizes (0.2 mm, 0.4 mm, 0.6 mm, and 0.8 mm) and in a four-prong configuration. The collapsed basket end of the instruments is advanced gently through the sclerotomy into the vitreous cavity until it reaches the fragment. The foreign body is then guided into the basket, the prongs are collapsed around it, and the unit is carefully extracted while avoiding traction on vitreous strands (Figure 3A).

Another potential tool for extraction of bulky or spherical IOFBs, is a salivary stone four-prong basket (Karl Storz Stone Extractor Basket, Karl Storz SE & Co., Germany), commonly used for retrieving sialoliths [18]. A 0.40 mm sialolith basket was successfully used by one of the authors in a separate case involving a glass IOFB, although this case has not yet been reported in the literature. These two basket instruments differ primarily in their external mechanisms for opening and closing the prongs.

Our case adds to the limited literature supporting the use of prong basket devices for retrieval of challenging IOFBs [11,19–22]. Removal of intravitreal glass fragments using conventional forceps is often limited by slippage, whereas extraction using a stone basket can provide an adjunctive tool for more secure and controlled alternative for capturing large, smooth or spherical fragments. Its use, however, is limited by reduced precision and lack of ocular specific design with limited tactile feedback and less precise opening/closing compared with intraocular forceps. The basket also requires an enlarged sclerotomy larger than for other retrieval tools. Careful case selection, complete vitrectomy, and controlled extraction are essential to minimize complications. Meticulous vitreous base shaving is a must when using these devices to prevent vitreous traction during extraction. With appropriate modifications, the four-prong basket tools may be adapted for ophthalmic surgery and represent valuable adjuncts for the removal of complex intraocular foreign bodies.

Meticulous vitreous base shaving is essential when using these devices to prevent vitreous traction during extraction. With appropriate modifications, the four-prong basket tools may be adapted for ophthalmic surgery and represent valuable adjuncts for the removal of complex intraocular foreign bodies.

Conclusion

Removal of intravitreal glass foreign bodies poses a significant surgical challenge when using conventional FB forceps due to frequent slippage. Our surgical case demonstrates that four-prong basket devices may offer an advantage over conventional forceps, most notably in the ability to securely capture large, smooth-surfaced or spherical shaped foreign bodies, thereby reducing the risk of slippage and iatrogenic retinal injury. Use of these instruments, however, requires meticulous shaving of the vitreous base to avoid vitreous traction during extraction. The device is not designed for intraocular microsurgery and may provide less tactile precision control compared with ophthalmic foreign body forceps. With appropriate modifications, the sialolith and nephrolith baskets may be successfully adapted for ophthalmic surgery.

Ethical Approval

This case report was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Case reports are exempt from IRB approval at our institution.

Statement of Informed Consent

Informed consent was not required as this case report does not contain any identifying information.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

2. Loporchio D, Mukkamala L, Gorukanti K, Zarbin M, Langer P, Bhagat N. Intraocular foreign bodies: A review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2016 Sep-Oct;61(5):582–96.

3. Zhang Y, Zhang M, Jiang C, Qiu HY. Intraocular foreign bodies in china: clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and visual outcomes in 1,421 eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011 Jul;152(1):66–73.e1.

4. Lesniak SP, Bauza A, Son JH, Zarbin MA, Langer P, Guo S, et al. Twelve-year review of pediatric traumatic open globe injuries in an urban U.S. population. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2012 Mar-Apr;49(2):73–9.

5. Nanda SK, Mieler WF, Murphy ML. Penetrating ocular injuries secondary to motor vehicle accidents. Ophthalmology. 1993 Feb;100(2):201–7.

6. Patel SN, Langer PD, Zarbin MA, Bhagat N. Diagnostic value of clinical examination and radiographic imaging in identification of intraocular foreign bodies in open globe injury. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2012 Mar-Apr;22(2):259–68.

7. Ruddat MS, Johnson MW. The use of perfluorocarbon liquid in the removal of radiopaque intraocular glass. Arch Ophthalmol. 1995 Dec;113(12):1568–9.

8. Gopal L, Banker AS, Deb N, Badrinath SS, Sharma T, Parikh SN, Shanmugham MP, Bhende PS, Das D, Mukesh BN. Management of glass intraocular foreign bodies. Retina. 1998;18(3):213–20.

9. Ghoraba H. Posterior segment glass intraocular foreign bodies following car accident or explosion. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2002 Jul;240(7):524–8.

10. Azad R, Sharma YR, Mitra S, Pai A. Triple procedure in posterior segment intraocular foreign body. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1998 Jun;46(2):91–2.

11. Francis AW, Wu F, Zhu I, de Souza Pereira D, Bhisitkul RB. Glass intraocular foreign body removal with a nitinol stone basket. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2019 Aug 10;16:100541.

12. Kuniyal L, Rishi E, Rishi P. Intraocular glass foreign body-Retained amiss! Oman J Ophthalmol. 2014 Jan;7(1):40–2.

13. Bhagat N, Nagori S, Zarbin M. Post-traumatic Infectious Endophthalmitis. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011 May-Jun;56(3):214–51.

14. Bapaye M, Shanmugam MP, Sundaram N. The claw: A novel intraocular foreign body removal forceps. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2018 Dec;66(12):1845–8.

15. Singh R, Kumar A, Gupta V, Dogra MR. 25-Gauge active aspiration silicon tip-assisted removal of glass and other intraocular foreign bodies. Can J Ophthalmol. 2016 Apr;51(2):97–101.

16. Liu CC, Tong JM, Li PS, Li KK. Epidemiology and clinical outcome of intraocular foreign bodies in Hong Kong: a 13-year review. Int Ophthalmol. 2017 Feb;37(1):55–61.

17. Erakgün T, Ates H, Akkin C, Kaskaloglu M. A simple "lasso" for intraocular foreign bodies. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers. 1999 Jan;30(1):63–6.

18. Karwowska NN, Turner MD. Etiology, diagnosis, and surgical management of obstructive salivary gland disease. Front Oral Maxillofac Med. 2021 Jun 10;3:17.

19. El-Baha SM, Abou Shousha MA, Hafez TA, Ahmed ISH. Evaluation of the use of NGage® Nitinol stone extractor for intraocular foreign body removal. Int Ophthalmol. 2021 Jun;41(6):2083–9.

20. McCarthy MJ, Pulido JS, Soukup B. The use of ureter stone forceps to remove a large intraocular foreign body. Am J Ophthalmol. 1990 Aug 15;110(2):208–9.

21. Berry DE, Walter SD, Fekrat S. A Frag Bag for Efficient Removal of Dislocated Nuclear Material. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging Retina. 2017 Dec 1;48(12):1006–8.

22. Durrani AK, Cherney EF, Shah RJ, Patel SN. Use of Tipless Kidney Stone Basket for Removal of Intraocular Foreign Bodies or Dislocated Cataract in Eyes With Posterior Staphyloma. Retina. 2019 Oct;39 Suppl 1:S54–7.