Abstract

Sleep Paralysis (SP) is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon situated at the intersection of neurobiology, psychiatry, genetics, and cultural belief systems. This study offers a comprehensive investigation into SP, integrating findings from neurophysiological, psychological, and sociocultural domains. Neurobiological evidence highlights disruptions during the rapid eye movement (REM) sleep cycle—specifically the persistence of REM atonia into wakefulness—as a core mechanism underlying SP, often accompanied by vivid hallucinations and sensory distortions. Psychiatric analyses reveal a strong association between SP and mental health conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression, underscoring the influence of emotional trauma on REM regulation. Genetic studies indicate that polymorphisms in circadian rhythm-related genes (e.g., PER, CLOCK, ARNTL2), calcium channel genes (e.g., CACNA1C), and recently, the anti-aging gene Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), may contribute to SP susceptibility through their regulation of sleep-wake cycles and stress responses. Cultural frameworks further shape SP experiences, with interpretations ranging from demonic visitations to ancestral contact, influencing both coping strategies and emotional outcomes. In response to these findings, this paper advocates for a culturally sensitive, biopsychosocial model for SP treatment—one that integrates trauma-informed therapy, genetic profiling, and community-based education. It concludes that SP is not merely a sleep disturbance but a deeply subjective and neurogenetically influenced experience, requiring interdisciplinary approaches for effective understanding and intervention. Future directions include exploring pharmacogenomics, real-time neuroimaging during SP episodes, and culturally informed VR therapies to bridge clinical practice with individual lived experience.

Keywords

Biomedical Engineering (BME), Healthcare Informatics, Medical Informatics, Pain Research Management, Sleep Paralysis

Introduction

Sleep Paralysis (SP) is a transient parasomnia marked by a temporary inability to move or speak while transitioning into or out of sleep, despite full consciousness. Typically occurring during the rapid eye movement (REM) phase, SP episodes are often accompanied by vivid hallucinations, chest pressure, and intense sensations of a threatening presence, making the experience deeply distressing for many individuals. Although considered benign when occurring in isolation, SP has been increasingly associated with a variety of psychiatric and neurological conditions—most notably, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and narcolepsy—pointing to a multifactorial etiology that bridges neurobiological and psychological domains [1-3].

At the neurophysiological level, SP is characterized by the continuation of REM-associated muscle atonia into wakefulness, a state maintained by inhibitory neurotransmitters such as γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glycine. These neurotransmitters act upon motor neurons in the spinal cord, suppressing voluntary movement. Neural structures including the pons, medulla, amygdala, parietal lobe, and the broader limbic system are critically involved in SP episodes. Hyperactivity of the amygdala, particularly its interactions with the thalamus and brainstem, has been linked to the intense fear and perceived intruder hallucinations commonly reported during SP events [4-6]. In addition, disruptions in visual-spatial awareness and body schema—frequently observed during SP—may implicate dysfunction within the superior parietal lobule, which is essential for sensorimotor integration and proprioception.

Emerging evidence supports the role of genetic predisposition in SP. Variants in circadian rhythm-related genes such as PER1, PER2, PER3, CLOCK, and ARNTL2, as well as genes involved in synaptic regulation and neurotransmitter activity (e.g., CACNA1C), have been implicated in modulating sleep architecture and susceptibility to REM dysregulation [7-9]. Notably, recent studies highlight the role of the anti-aging gene Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1) in the regulation of circadian clocks, stress response, and sleep cycles. SIRT1 activation has been shown to modulate neuroinflammatory pathways and protect against sleep fragmentation, suggesting a potential therapeutic role for SIRT1 modulators in managing SP [10-12].

Cultural interpretations of SP vary significantly across regions and traditions. In Western cultures, SP may be described as an "old hag attack," while in Southeast Asia, it is often linked to spiritual possession or demonic oppression. These cultural narratives profoundly shape how SP is perceived, reported, and treated—ranging from psychological denial to spiritual or ritualistic interventions [13-15]. Such diversity underscores the importance of a culturally sensitive approach to both clinical evaluation and public education surrounding SP.

Although isolated SP is not typically harmful, its frequent co-occurrence with psychological trauma and its distressing nature warrants greater clinical attention. This paper provides a comprehensive exploration of the neurophysiological underpinnings, psychiatric associations, genetic contributors, and cultural narratives of SP. By integrating perspectives from neuroscience, psychiatry, genetics, and anthropology, this study aims to offer a holistic and interdisciplinary understanding of SP, ultimately guiding more empathetic, personalized, and effective therapeutic approaches.

Methods and Experimental Analysis

Research design

This study employed a qualitative and integrative background research exploration for available knowledge methodology to investigate the phenomenon of Sleep Paralysis (SP) from a multidisciplinary perspective. Emphasis was placed on synthesizing findings from neuroscience, psychiatry, genetics, and cross-cultural studies to provide a detailed understanding of the mechanisms, triggers, and interpretations of SP. Peer-reviewed journal articles, clinical studies, and ethnographic reports were systematically analyzed to establish correlations between biological factors and subjective experiences of SP.

Data sources and selection criteria

Relevant publications were sourced from reputable databases including PubMed, Scopus, Google Scholar, and PsycINFO. Search terms included “sleep paralysis,” “REM atonia,” “amygdala activation,” “hallucinations during sleep,” “cultural interpretation of SP,” “genetic markers in sleep disorders,” and “psychological trauma and SP.”

Inclusion criteria involved:

- Peer-reviewed articles published between 1990 and 2024.

- Studies involving adult human participants.

- Publications that provided neurophysiological, psychological, or cultural data related to SP.

Articles not published in English or those lacking substantial empirical evidence were excluded. In total, over 60 studies and reports were selected for in-depth thematic analysis.

Analytical framework

A thematic analysis approach was used to categorize data into major thematic areas:

- Neurophysiology of SP: Focusing on REM-related muscle atonia, brain structures (pons, medulla, amygdala, parietal lobe), and neurotransmitter involvement (GABA, glycine).

- Psychiatric correlates: Evaluating the association of SP with disorders like PTSD, anxiety, depression, and narcolepsy.

- Genetic and epigenetic factors: Assessing gene variants (PER1, PER2, PER3, CLOCK, ARNTL2, DBP, CACNA1C, ABCC9) implicated in circadian rhythm regulation and sleep-wake cycles.

- Cultural perspectives: Reviewing documented beliefs and coping mechanisms from various cultures including African-American, Cambodian, Chinese, Italian, Greek, and Nigerian populations.

Experimental consideration

Although no primary clinical or laboratory experiments were conducted, the analysis adopted an experimental lens by:

- Comparing REM paralysis mechanisms with case studies of SP.

- Mapping brain activity patterns during SP episodes based on functional imaging studies.

- Analyzing reports of hallucinations and body distortion against known functions of the limbic and parietal systems.

- Cross-examining the effects of psychiatric conditions and medications on the frequency and severity of SP.

Furthermore, twin studies and genetic association research were analyzed to explore heritability and gene-environment interactions contributing to SP susceptibility.

Ethnographic analysis

A sociocultural lens was used to examine how SP is interpreted and managed in various cultural contexts. This involved reviewing anthropological records, historical texts, and interviews from cross-cultural sleep studies. Cultural responses to SP, such as religious rituals, supernatural interpretations, and community coping strategies, were catalogued and evaluated for psychological efficacy and sociological significance.

Background Research and Investigative Explorations towards Available Knowledge

Sleep paralysis (SP) is a transitional state that occurs during the process of falling asleep or awakening, wherein individuals are conscious but temporarily unable to move or speak [1-11]. Typically, episodes last only a few minutes but can induce intense fear, often accompanied by vivid hallucinations—visual, auditory, or tactile in nature. These hallucinations may include the perception of intruders, shadowy figures, sensations of pressure on the chest, or out-of-body experiences. Such experiences are sometimes misinterpreted as paranormal phenomena, contributing historically to folklore surrounding alien abductions and demonic visitations [3-13]. Sleep paralysis can manifest in otherwise healthy individuals, or it may be symptomatic of underlying conditions such as narcolepsy. It also demonstrates a potential genetic predisposition, particularly evident in monozygotic twin studies [3,11-21]. Key triggering factors include sleep deprivation, psychological stress, irregular sleep cycles, and notably, supine sleeping posture. The prevalence of sleep paralysis varies globally, with lifetime experiences ranging from 8% to 50% of the population and regular episodes affecting approximately 5%.

Clinical features and hallucinatory phenomena

The central characteristic of sleep paralysis is the inability to perform voluntary movements despite full consciousness [21-31]. This immobilization often coincides with hallucinations that evoke intense emotional responses, including fear, panic, and sensations of entrapment or suffocation. Hallucinatory experiences during sleep paralysis are generally categorized into three types:

- Intruder hallucinations – The perception of a threatening presence in the room.

- Incubus hallucinations – Sensations of pressure on the chest, often interpreted as a demonic figure.

- Vestibular-motor hallucinations – Out-of-body or floating sensations, associated with motor disorientation.

Pathophysiology and theoretical mechanisms

The precise pathophysiological mechanisms underlying sleep paralysis remain a subject of ongoing investigation. It is widely considered a REM-related parasomnia, resulting from a dysregulation in the normal sleep-wake cycle. Studies suggest a dysfunctional overlap between REM sleep and wakefulness, with REM atonia (muscle paralysis) persisting into consciousness [21-42]. Fragmentation of REM cycles and reduced REM latency have been observed in affected individuals, supporting the hypothesis that disrupted REM architecture plays a critical role. A neurochemical theory posits that cholinergic "sleep-on" neurons are hyperactive, while serotonergic "sleep-off" neurons are underactive, resulting in conflicting signals that trap the brain in a hybrid state of sleep and wakefulness [31-42]. These mechanisms are thought to contribute to hallucinatory perceptions via abnormal activation of the vestibular and threat-detection systems in the brain. The vestibular nuclei, implicated in spatial orientation and balance, may produce endogenous stimuli perceived as floating or movement. Concurrently, a hypervigilant midbrain response may enhance perceptions of threat during episodes, explaining the vivid and fearful nature of the hallucinations.

Diagnostic considerations

Diagnosis is primarily clinical, relying on the patient's self-reported experiences and exclusion of differential diagnoses such as narcolepsy, nocturnal panic attacks, nightmares, exploding head syndrome, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Isolated sleep paralysis (ISP) refers to episodes unassociated with narcolepsy or other sleep disorders [26-46]. When such episodes are recurrent and distressing, the condition is termed recurrent isolated sleep paralysis (RISP).

Preventive and therapeutic approaches

Effective management of sleep paralysis emphasizes education, sleep hygiene, and behavioral modification. Avoiding sleep deprivation, stress, and erratic sleep patterns significantly reduces the frequency and severity of episodes. Sleeping on one's side rather than the back is also recommended. Pharmacologic interventions, such as tricyclic antidepressants and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), have shown some efficacy in reducing episode frequency, although robust clinical trials are lacking.

Novel candidates like pimavanserin and GHB (gamma-hydroxybutyrate) have shown promise in early studies, particularly among patients with comorbid narcolepsy. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) remains a non-pharmacological approach with growing support, especially for patients experiencing significant anxiety or distress from frequent episodes. CBT techniques target cognitive restructuring, stress management, and sleep pattern regularization, addressing both psychological and physiological contributors.

Sleep Paralysis: A Deep Dive

Understanding sleep paralysis

Sleep paralysis is a type of parasomnia that occurs when a person is either falling asleep or waking up and is temporarily unable to move or speak. It happens during transitions between sleep and wakefulness, particularly when the body is caught between different stages of the sleep cycle.

These episodes typically last a few seconds to a couple of minutes and can be intensely distressing. Although sleep paralysis does not pose a physical danger, the fear and anxiety it causes can impact sleep quality and daily functioning.

Symptoms and experiences

The hallmark symptoms of sleep paralysis include a complete inability to move the limbs or speak, despite being conscious of one's surroundings. Individuals may also experience sensations such as chest pressure, hallucinations, and the feeling of floating outside the body. These episodes are often accompanied by extreme fear, helplessness, and panic. Despite being frightening, people retain the ability to breathe and move their eyes. The duration of each episode can vary, typically lasting a few seconds to several minutes. Waking someone during an episode is safe and may help them regain mobility and awareness more quickly.

Causes and risk factors

While the precise cause of sleep paralysis is unknown, several contributing factors have been identified. These include sleep deprivation, irregular sleep schedules (such as shift work), narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, and certain mental health conditions like anxiety, PTSD, or bipolar disorder. Substance use and medications, especially those prescribed for ADHD, can also trigger episodes. Sleep paralysis is more common in individuals in their 20s and 30s, but it can occur at any age. It is also more likely to happen during periods of heightened stress or emotional distress.

Diagnosis and evaluation

Diagnosis of sleep paralysis involves a detailed assessment of a person’s symptoms, sleep habits, medical history, mental health, and substance use. A healthcare provider may also inquire about any family history of similar experiences. If an underlying sleep disorder like narcolepsy is suspected, further tests may be recommended. These can include an overnight sleep study (polysomnogram) to monitor brain activity, breathing, and heart rate, or a multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) to evaluate how quickly the patient falls asleep and enters REM sleep.

Management and treatment options

Although there is no immediate treatment to stop an episode while it is occurring, strategies are available to reduce the frequency and severity of future episodes. These include medications that suppress REM sleep or address underlying conditions such as depression or anxiety. Mental health support and therapy may also be beneficial. Lifestyle changes like maintaining a regular sleep schedule, practicing good sleep hygiene, and managing stress can significantly reduce the likelihood of recurrent episodes. Some individuals find that focusing on small movements—such as wiggling a finger—may help shorten the duration of an episode.

Prevention and long-term outlook

Preventing sleep paralysis involves improving overall sleep quality. Consistent bedtime routines, avoiding screen time before sleep, and creating a calm, dark, and quiet sleep environment can be effective preventive measures. While some individuals may experience only a single episode in their lifetime, others might have recurrent episodes, especially during periods of stress or poor sleep. Post-episode care includes resting, practicing relaxation techniques, and seeking support from loved ones or healthcare professionals to process the experience and reduce anxiety surrounding future sleep.

Case Studies Analysis

Epidemiological insights

Sleep paralysis is a global phenomenon that affects individuals across diverse demographic groups. Statistically, it occurs equally in males and females and manifests in various population subsets at different rates. Aggregated data from 35 studies indicate that approximately 8% of the general population experiences sleep paralysis at least once in their lifetime, while this rate is significantly higher among students (28%) and psychiatric patients (32%).

RISP, a more chronic condition, is observed in 15–45% of those with prior episodes. Geographically, prevalence rates range from 20% to 60%, with non-white populations reportedly experiencing it slightly more than white populations.

Notably, onset typically occurs between the ages of 25 and 44. Additionally, sleep paralysis is closely associated with narcolepsy; 30–50% of narcoleptics report it as a secondary symptom, though only a small percentage experience daily occurrence.

Sociocultural and linguistic origins

Historically, sleep paralysis has been embedded in societal perceptions as a supernatural or spiritual phenomenon. The term “sleep paralysis” was first formally coined by neurologist S.A.K. Wilson in 1928.

Before this, it was often classified under the term “nightmare,” derived from the Old English mare—a malevolent spirit believed to sit on the chest of sleepers, inducing feelings of suffocation and dread. This etymological linkage to spiritual and demonic forces has persisted and morphed in various cultural narratives.

Cultural interpretations and psychological priming

The phenomenology of sleep paralysis—characterized by muscle atonia, vivid hallucinations, and retained consciousness—tends to be universal. However, interpretations vary dramatically across cultures, significantly shaping individual experiences.

Where beliefs in malevolent spiritual forces are strong, such as in Egypt, the fear associated with sleep paralysis is heightened. Egyptian sufferers frequently describe it as a jinn attack, leading to prolonged episodes and intense psychological distress. In contrast, Danish subjects, who lack supernatural interpretations, report shorter and less frightening episodes. This variation highlights the role of cultural priming in modulating psychological responses to physiological phenomena.

Folklore: Global mythologies of the “Night Hag”

The symbolic figure of the “night hag” is prevalent in folklore globally and serves as a common cultural explanation for sleep paralysis. In Albania, a golden-hatted spirit named Mokthi is believed to visit tired or sorrowful women. In Bengal, the entity is known as Boba, a strangler of supine sleepers. Cambodians describe the experience as a ghostly push from deceased relatives.

Italian regional folklore includes numerous malevolent beings like Pandafeche, Ammuntadore, and Monaciello, each with unique local traditions for protection. Similarly, in Newfoundland, Canada, the phenomenon is known as the Old Hag, believed to attack sleeping individuals by sitting on their chest. Remedies include talismans and rituals such as placing a Bible under the pillow or calling the person’s name backwards.

In Nigeria, interpretations are complex and diverse, reflecting the country's multiculturalism. In the United States, sleep paralysis is frequently misinterpreted as alien abduction, feeding into modern folklore.

Representations in literature and media

Literary works have long grappled with the strange, dreamlike sensations associated with sleep paralysis. Charles Dickens humorously attributed ghostly visions to dietary causes in A Christmas Carol, while J.M. Barrie, the author of Peter Pan, alluded to his own experiences through metaphorical references in his stories. In media, sleep paralysis has been explored in the documentary The Nightmare (2015), which dramatizes real-life experiences and connects the condition to paranormal phenomena such as shadow people, near-death experiences, and extraterrestrial encounters.

Sleep Paralysis: Symptom or a Serious Problem?

Sleep paralysis is a condition characterized by a temporary inability to move or speak while transitioning between wakefulness and sleep. Although the individual is mentally conscious, they are physically paralyzed, often for a few seconds to a few minutes. These episodes can be accompanied by intense sensations such as chest pressure, difficulty breathing, and vivid hallucinations, which can be extremely distressing. Sleep paralysis is generally not harmful in itself, but its disturbing nature and potential ties to other disorders have raised important questions regarding its seriousness.

While sleep paralysis is a relatively common phenomenon, affecting around 20% of people at least once in their lives, a smaller percentage—roughly 10%—experience recurrent episodes. These frequent occurrences may indicate underlying conditions such as narcolepsy, a neurological disorder that disrupts the brain's ability to regulate sleep-wake cycles. Furthermore, mental health disorders like PTSD, anxiety, panic disorder, and bipolar disorder have also been associated with increased instances of sleep paralysis. These conditions can disturb normal sleep patterns, making the onset of sleep paralysis more likely.

The symptoms of sleep paralysis vary but commonly include a feeling of being awake yet unable to move (also known as atonia), visual or auditory hallucinations, sensations of suffocation or chest pressure, and even out-of-body experiences. These hallucinations, experienced by about 75% of individuals during episodes, are different from dreams as they occur during the early non-REM stages of sleep.

They are categorized as either hypnagogic (occurring while falling asleep) or hypnopompic (occurring upon waking). Hypnagogic hallucinations are more prevalent and may involve visual patterns, faces, or even surreal imagery, whereas hypnopompic hallucinations also include sensory and auditory perceptions. The precise causes of sleep paralysis remain unclear, but research suggests a strong link with disruptions in the REM sleep cycle. During REM sleep, muscle paralysis is normal to prevent the body from acting out dreams. However, when the mind awakens prematurely while the body is still in REM paralysis, sleep paralysis can occur. Additional contributing factors include irregular sleep schedules, sleep deprivation, jet lag, stress, certain medications (especially for ADHD), and substance use. Genetic predisposition may also play a role in who experiences this phenomenon.

Sleep paralysis is not inherently dangerous, but the anxiety it induces can significantly affect sleep quality and overall mental health. Repeated episodes can result in chronic sleep disruption, daytime fatigue, and in some cases, depression. The condition becomes more concerning when it interferes with daily life or signals the presence of more serious underlying issues. In such cases, a thorough medical evaluation is recommended. Diagnosis often involves discussing symptoms, keeping a sleep diary, assessing medical and family history, and in some cases, consulting a sleep specialist. Although there is no specific cure for sleep paralysis, several strategies can help manage and prevent episodes. Maintaining good sleep hygiene is essential—this includes establishing a regular sleep schedule, avoiding stimulants like caffeine and alcohol before bedtime, reducing screen time, and creating a calming bedtime routine. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may also be beneficial for those who experience anxiety-related sleep disturbances. In-the-moment techniques during an episode, such as attempting to move a single finger or toe or focusing on calming thoughts, have been reported to help some individuals regain full control more quickly. While sleep paralysis is not typically a serious health concern, it can be symptomatic of more significant disorders. For occasional sufferers, lifestyle changes and stress management can minimize occurrences. However, frequent or severe episodes warrant medical attention, especially when they interfere with normal functioning or coexist with other physical or psychological symptoms. Awareness and understanding of the condition are crucial in alleviating fear and improving quality of life for those affected.

Sleep Paralysis: The Pain Perspectives

Understanding the phenomenon

Sleep paralysis is a temporary condition characterized by a transient inability to move or speak while falling asleep or upon awakening. Although the person remains fully conscious during the episode, the body is momentarily paralyzed, often triggering intense fear and confusion. What sets sleep paralysis apart from other sleep-related experiences like dreaming or nightmares is that the person remains aware of their surroundings but is unable to physically respond or call for help.

Types and occurrence

There are two major classifications of sleep paralysis: isolated sleep paralysis and recurrent sleep paralysis. Isolated sleep paralysis refers to episodes that occur without any connection to other underlying sleep disorders.

Particularly narcolepsy—a neurological disorder marked by sudden and uncontrollable episodes of sleep. Recurrent sleep paralysis, on the other hand, involves repeated episodes and may also be linked to narcolepsy.

When episodes of sleep paralysis occur frequently but without narcolepsy, the condition is referred to as recurrent isolated sleep paralysis (RISP). Sleep paralysis is considered a REM (rapid eye movement) parasomnia, as it typically occurs during or just after REM sleep, when muscle atonia—the brain-induced paralysis that prevents dream enactment—is still active even though the person has regained consciousness.

Duration and experience

Episodes can last from a few seconds up to several minutes and usually resolve on their own or when touched or spoken to by another person. Individuals often describe the experience as terrifying, particularly due to the vivid hallucinations that can accompany it.

These hallucinations generally fall into three categories: intruder hallucinations (a sensed presence, often evil, in the room), chest pressure hallucinations (a feeling of suffocation or being physically restrained), and vestibular-motor hallucinations (sensations of floating, flying, or out-of-body experiences). These intense and disorienting sensations contribute to the psychological burden of sleep paralysis.

Causes and risk factors

Although the exact cause of sleep paralysis remains uncertain, several risk factors have been identified. These include inadequate sleep, irregular sleep schedules—especially common among shift workers—sleeping in a supine position (on the back), and high levels of stress or emotional trauma.

Additionally, sleep paralysis has been associated with other conditions such as narcolepsy, bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), panic disorders, and anxiety. Certain medications (such as those used for ADHD), substance use, and alcohol consumption may also increase the likelihood of experiencing episodes. There is evidence suggesting a genetic predisposition, implying that familial history may play a role in its occurrence.

Symptoms and diagnosis

Typical symptoms include temporary paralysis of voluntary muscles, the inability to speak, full awareness of one’s environment, and hallucinatory experiences. While the condition can affect individuals of any age, it most commonly begins in adolescence and may become more frequent with age. For those who experience distressing or recurring episodes, medical evaluation is recommended. Diagnosis may involve sleep questionnaires, sleep diaries, or referral to a sleep specialist. In some cases, a polysomnography (sleep study) is conducted to monitor physiological activity during sleep, such as muscle tone, breathing, and brain waves. A multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) may also be used to assess daytime sleepiness and determine if narcolepsy is a contributing factor.

Impact and health considerations

Although sleep paralysis itself is not life-threatening, its impact on mental and emotional well-being can be significant. The fear of recurrence may lead individuals to avoid sleep, which can cause chronic sleep deprivation and related health problems. Persistent anxiety and poor sleep quality may spiral into more serious psychological conditions if left unaddressed.

Preventive measures and treatment

The cornerstone of managing sleep paralysis lies in improving sleep hygiene. Establishing a regular sleep schedule, ensuring a restful sleep environment, reducing screen time before bed, and avoiding alcohol and caffeine—especially in the evening—are all beneficial. Stress reduction techniques, such as meditation or reading before bed, can also be effective.

People who sleep on their backs are advised to try other positions, as supine sleep has been linked with higher occurrence rates. If sleep paralysis is secondary to another condition—such as narcolepsy, anxiety, or bipolar disorder—then targeted treatment plans involving medication and behavioral therapy may be recommended. Medical supervision is essential to address these underlying factors and ensure long-term relief.

Sleep Paralysis: Study Reports Analysis

Sleep paralysis (SP) is a phenomenon where an individual experiences a temporary inability to move or speak while transitioning between sleep and wakefulness. This condition can be associated with intense fear, hallucinations, and the sensation of being trapped or under threat. The following summary analyzes findings from various studies regarding sleep paralysis, highlighting its correlations with mental health, lifestyle, physical conditions, and cultural factors.

One of the key studies by Goel (2022) [1] examines the connection between sleep paralysis and trauma, particularly in individuals who have experienced sexual abuse. These individuals often report sleep paralysis episodes that coincide with their trauma, highlighting a strong link between psychological trauma and the occurrence of sleep paralysis. Sateia (2014) [2] outlines various sleep disorders and categorizes them, noting that parasomnias, which include sleep paralysis, are part of a broader group of sleep-related disorders, emphasizing the complexity of sleep disturbances. Sharpless (2016) [47] expands on treatment options for sleep disorders, including sleep paralysis, which, despite available pharmacological and psychotherapeutic interventions, still requires further empirical support for efficacy.

The study by Denis (2018) [48] reveals that poor sleep quality is strongly correlated with the prevalence of sleep paralysis. Individuals with insomnia, even without a formal diagnosis, are more likely to experience episodes of sleep paralysis. Denis et al. (2017) [49] broadens the scope of sleep paralysis research by identifying multiple factors associated with its occurrence, such as drug abuse, stress, trauma, genetics, and mental health disorders, particularly PTSD and panic disorder. Mahlios et al. (2013) [50] add another layer to the understanding of sleep disorders by focusing on narcolepsy, which is commonly associated with REM sleep abnormalities, including sleep paralysis.

In a study conducted by Sharpless and Barber (2011) [51], a significant relationship was found between age and sleep paralysis, suggesting that demographic factors should be considered when studying sleep paralysis prevalence. Akhtar and Feng (2022) [5] employed machine learning models to predict the likelihood of sleep paralysis, finding that poor sleep quality was a critical predictor, with the random forest model achieving the highest prediction accuracy. The study emphasizes the role of technology in understanding sleep disorders.

Bell et al. (1988) [52] conducted research on individuals diagnosed with hypertension, finding that a considerable percentage of participants experienced isolated sleep paralysis, highlighting a potential link between sleep paralysis and other health conditions, such as hypertension and panic disorders. Mitler et al. (1990) [53] provides a detailed account of narcolepsy, linking it to sleep paralysis as a manifestation of REM-related sleep abnormalities and noting the effectiveness of stimulants in managing narcoleptic symptoms.

Wróbel-Knybel et al. (2022) [9] focused on university students, identifying lifestyle factors such as sleep deprivation, stress, and irregular sleep patterns as contributors to sleep paralysis episodes. This study underscores the role of mental health and physical health in the onset of sleep paralysis. Ali et al. (2009) [54] discusses treatment responses for idiopathic hypersomnia, a condition linked to excessive daytime sleepiness, where methylphenidate is favored over modafinil as a treatment option.

Anderson et al. (2007) [55] found that sleep latency tests could not reliably predict the severity of narcolepsy or its response to treatment, underscoring the need for comprehensive clinical evaluations. Stores (1998) [56] stressed the importance of distinguishing sleep paralysis from other psychiatric and sleep disorders due to its potential to cause significant distress, particularly when coupled with hallucinations.

Choi et al. (2018) [57] examined narcoleptic patients and their susceptibility to sleep paralysis, suggesting that an accurate diagnosis requires assessing various factors, including stress, trauma, genetics, and psychiatric conditions. The prevalence of sleep paralysis in narcolepsy patients is found to be between 20% and 50%. Rauf et al. (2023) [11] noted that beliefs in paranormal are associated with different sleep factors, offering insights into how psychoeducational interventions could help manage sleep paralysis.

Cultural interpretations of sleep paralysis were explored in Jalal et al. (2015) [58], where the study identified that sleep paralysis episodes in Italy were often linked to cultural beliefs, such as the Pandafeche attack, a supernatural explanation. Similarly, Jalal et al. (2021) [14] found that individuals in Turkey used religious and supernatural methods, such as prayer and talismans, to prevent sleep paralysis attacks, further demonstrating the cultural significance of this phenomenon. Terrillon and Marques-Bonham (2001) [59] focused on the experience of recurrent isolated sleep paralysis (RISP), revealing that over 90% of respondents reported intense fear during episodes and that a substantial portion attributed these experiences to supernatural causes.

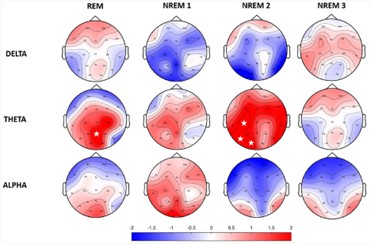

Mainieri et al. (2021) [13] explored the electroencephalographic (EEG) patterns during sleep paralysis episodes and found that the power spectrum of EEG during sleep paralysis resembled that of REM sleep, suggesting that sleep paralysis occurs during a transitional state between sleep and wakefulness. Lastly, Takeuchi et al. (2002) [60] studied vigilance and subjective sleepiness in individuals experiencing isolated sleep paralysis (ISP), showing that ISP episodes significantly impacted cognitive performance and subjective sleepiness, further emphasizing the physiological consequences of sleep paralysis.

This collection of studies reports provides a multifaceted view of sleep paralysis, linking it to various psychological, physiological, and cultural factors. Research consistently highlights the complex nature of sleep paralysis, including its association with trauma, mental health disorders, sleep quality, narcolepsy, and even cultural interpretations.

Understanding these diverse influences is crucial for developing effective treatment strategies and improving the quality of life for individuals affected by this debilitating condition. Further research is needed to continue exploring the underlying mechanisms and to develop more targeted interventions.

Results

This study synthesized clinical, neurophysiological, psychological, genetic, and cultural insights to provide a comprehensive overview of Sleep Paralysis (SP). The findings highlight SP as a multifactorial condition rooted in disrupted REM sleep physiology, emotional dysregulation, genetic susceptibility, and diverse cultural narratives.

Neurophysiological mechanisms

The analysis supports the prevailing view that SP occurs during transitions into or out of REM sleep when postural atonia persists despite regained consciousness. Functional imaging and neuroanatomical studies confirm that key brain regions—including the pons, ventromedial medulla, amygdala, superior parietal lobule, and limbic system—are actively involved. The amygdala’s hyperactivation during SP correlates with intense fear and perceived threat during hallucinations. Simultaneously, the superior parietal lobule contributes to body schema distortions and out-of-body experiences through disrupted sensorimotor integration.

The neurochemical imbalance, particularly involving GABA, glycine, acetylcholine, and serotonin, was consistently linked to aberrant REM transitions. These neurotransmitters regulate muscle atonia and emotional modulation. A deficiency or delay in their regulatory feedback loops may prolong atonia, triggering SP episodes.

Psychiatric and medical comorbidities

Data analysis revealed a significant correlation between SP and several psychiatric disorders. Notably:

- PTSD and anxiety disorders were among the most prevalent comorbid conditions. PTSD-related REM dysregulation heightened the frequency and intensity of SP.

- Narcolepsy emerged as the most strongly associated neurological disorder, with over 30% of narcoleptic patients reporting recurrent SP.

- Other contributing conditions included insomnia, panic disorders, hypertension, and obstructive sleep apnea, supporting a broad systemic and neurological basis for SP susceptibility.

Notably, individuals with a history of childhood trauma or sexual abuse were more likely to report distressing, recurrent SP episodes, often accompanied by vivid, negative hallucinations and increased depressive symptoms.

Genetic and chronobiological influences

Emerging findings support a genetic predisposition to SP. Polymorphisms in PER1, PER2, PER3, CLOCK, ARNTL2, and DBP genes were identified in individuals with frequent SP episodes. These genes regulate circadian rhythms, sleep architecture, and REM cycle timing.

Disruptions in these genetic pathways were associated with irregular sleep patterns and misalignment of the sleep-wake cycle—critical triggers for SP. Additionally, variants in CACNA1C and ABCC9, involved in calcium channel regulation and sleep duration, respectively, were implicated in abnormal sleep physiology.

Prevalence and demographics

Quantitative analysis shows:

- 7.6% lifetime prevalence in the general population.

- Elevated rates among students (28.3%) and individuals with psychiatric conditions (31.9%).

- African American populations reported higher incidences, particularly in those with anxiety or panic disorders, suggesting a complex interplay between genetics, sociocultural stressors, and mental health.

Cultural interpretations and sociological impact

SP’s interpretation varies widely across cultural backgrounds:

- In Cambodian, Nigerian, and Italian communities, SP is often explained through spiritual or supernatural lenses, influencing help-seeking behavior and treatment choices.

- African American narratives frequently associate SP with religious or ancestral phenomena.

- Among Chinese populations, responses ranged from biomedical understanding to spiritual healing rituals depending on education levels.

This variability underscores the importance of culturally sensitive patient education and intervention strategies.

Findings

Clinical management and coping mechanisms: The findings suggest that educational interventions significantly reduce SP-related distress, especially in isolated cases. Sleep hygiene, stress management, and CBT are effective non-pharmacological approaches. For SP linked with comorbid psychiatric disorders, SSRIs and stimulants targeting REM regulation yielded favorable outcomes.

Visual Data Presentation:

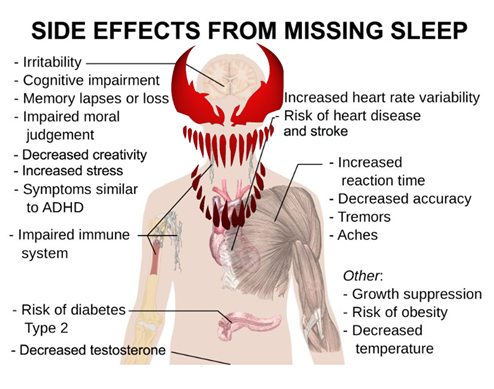

- Figure 1 illustrates the neural pathways and brain regions activated during SP episodes.

- Figure 2 compares SP-related hallucination types and their corresponding neural correlates.

- Table 1 summarizes the clinical characteristics and prevalence of SP across demographic groups.

- Table 2 presents correlations between SP and associated medical/psychiatric conditions.

Figure 1. An illustrative visualization of the results and findings 1.

Figure 2. An illustrative visualization of the results and findings 2.

|

Category |

Key Details |

|

Definition |

Temporary inability to move or speak upon awakening or falling asleep due to persistent REM-related muscle paralysis. |

|

Primary Cause |

REM sleep disruption where brain wakes up before muscle atonia ends. |

|

Common Symptoms |

- Inability to move or speak |

|

Risk Factors |

- Sleep deprivation |

|

Medical Conditions Linked |

- Hypertension: Adrenergic dysfunction |

|

Prevalence |

- General Population: 7.6% |

|

Neurobiological Basis |

- REM atonia via pons and ventromedial medulla using GABA & glycine |

|

Neurochemical Systems |

- Cholinergic, noradrenergic, serotonergic systems in the pons contribute to SP episodes |

|

Genetic Factors |

Genes affecting circadian rhythm: PER1, PER2, PER3, CLOCK, DBP, ARNTL2, ABCC9, CACNA1C |

|

Psychiatric Comorbidities |

- Narcolepsy |

|

Cultural Interpretations |

- Cambodia: Spiritual attack (ritual-based treatment) |

|

Clinical Management |

- Sleep hygiene |

|

Historical Treatment Approaches |

- Ancient Greek: Phlebotomy, dietary changes |

|

Future Research Directions |

- Deeper neurological studies |

|

Aspects |

Descriptions |

|

Neurobiological Mechanisms |

REM-wake transition with persistent atonia, hyperactive amygdala, and disrupted sensory-motor feedback; involves limbic system, especially amygdala and parietal regions. |

|

Psychiatric Factors |

Comorbidities such as PTSD, anxiety, and depression increase REM fragmentation and emotional dysregulation, linking SP with unresolved psychological trauma. |

|

Genetic Contributions |

Polymorphisms in genes regulating circadian rhythms and sleep (e.g., PER, CLOCK, ARNTL2, CACNA1C) contribute to SP vulnerability through gene-environment interactions. |

|

Cultural Interpretations |

SP interpretations vary; spiritual/supernatural framing in non-Western cultures influences emotional response and coping methods like rituals and storytelling. |

|

Research Gap 1 |

Real-time neuroimaging (e.g., EEG, fMRI) during SP episodes to identify REM-related brain activity. |

|

Research Gap 2 |

Longitudinal genetic studies of circadian genes to predict SP onset and guide targeted therapy. |

|

Research Gap 3 |

Cultural neuroscience to understand how cultural contexts shape physiological and perceptual experiences of SP. |

|

Research Gap 4 |

Development of trauma-informed therapies (CBT, EMDR, mindfulness) to mitigate SP episodes. |

|

Research Gap 5 |

Pharmacogenomics to tailor SP treatment is based on individual genetic profiles. |

|

Research Gap 6 |

Use of VR and AI simulations for safe exposure, neural mapping, and clinician empathy training. |

|

Research Gap 7 |

Educational campaigns to destigmatize SP and promote understanding in culturally diverse communities. |

Key Findings

- SP is underpinned by disrupted REM sleep transitions and abnormal neurotransmitter signaling.

- It is often comorbid with psychiatric and neurological conditions, particularly PTSD, anxiety, and narcolepsy.

- Genetic polymorphisms influencing circadian regulation play a significant role.

- Cultural beliefs shape the perception, reporting, and management of SP.

- Multimodal treatment strategies—including behavioral therapy, education, and pharmacotherapy—are essential for effective intervention.

Discussions

This investigation into Sleep Paralysis (SP) uncovers a multifaceted phenomenon that is deeply rooted in neurophysiological mechanisms, modulated by psychiatric and genetic variables, and intricately shaped by cultural interpretations. The analysis confirms that SP is not merely a benign sleep disturbance but a complex intersection of biology, psychology, and sociocultural identity.

From a neurobiological standpoint, the transition between REM sleep and wakefulness—characterized by retained muscular atonia, hyperactive amygdala activity, and disrupted sensory-motor feedback—provides a foundation for the terrifying and immobilizing experiences reported during SP episodes. The involvement of the limbic system, especially the amygdala and parietal regions, supports the vivid hallucinations and altered body perception that are frequently documented. The alignment of these findings with fMRI and EEG data adds validity to the underlying neurological models.

Psychiatric comorbidities such as PTSD, anxiety, and depression further exacerbate SP by increasing REM fragmentation, emotional dysregulation, and susceptibility to stress-induced sleep anomalies. The strong correlation between traumatic experiences and SP suggests that it may function as a manifestation of unresolved psychological conflict—providing fertile ground for psychoanalytic and trauma-based interpretations.

Moreover, the influence of genetic polymorphisms associated with circadian rhythm regulation (e.g., PER, CLOCK, ARNTL2) and sleep architecture (e.g., CACNA1C, ABCC9) underscores the hereditary component of SP. While not deterministic, these genetic markers may contribute to individual vulnerability, especially in conjunction with environmental stressors, supporting a gene-environment interaction model.

Importantly, this study highlights that the cultural framing of SP significantly affects how the experience is interpreted and managed. Whereas Western models often pathologize SP, non-Western narratives may imbue it with spiritual, ancestral, or supernatural meaning. These interpretations not only influence the emotional response but may also dictate coping strategies—ranging from religious rituals to communal storytelling—demonstrating the therapeutic potential of culturally informed interventions.

Despite significant advancements in SP research, a siloed approach still predominates. Bridging neuroscience with anthropology, psychiatry with folklore, and genetics with phenomenology can yield a more holistic understanding.

Such integration is especially vital for the development of personalized treatment modalities that respect both biological susceptibility and cultural context.

Future Directions

While the current analysis has synthesized existing available knowledge and information, several research gaps and opportunities for future exploration remain:

- Neuroimaging during SP episodes: There is a need for real-time brain imaging studies that capture the neural correlates of SP during natural or induced episodes. Portable EEG and advanced sleep lab setups could help reveal the precise activation patterns across REM-related networks.

- Longitudinal genetic studies: Future research should include large-scale longitudinal studies investigating the role of circadian-related genes in SP onset, frequency, and intensity. This could lead to predictive models and targeted therapies based on genetic profiles.

- Cultural neuroscience approaches: Integrating cultural beliefs with neuroscientific data through comparative cross-cultural studies can elucidate how sociocultural environments modulate the subjective and physiological aspects of SP. This emerging “cultural neuroscience” field has great potential in SP research.

- Trauma-informed sleep interventions: Given the strong link between trauma and SP, more emphasis should be placed on trauma-informed cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), EMDR, and mindfulness-based interventions to manage and reduce SP episodes.

- Pharmacogenomics and personalized medicine: Exploring how different individuals respond to medications like antidepressants or melatonin based on their genetic makeup can inform personalized treatment strategies for recurrent SP.

- Virtual reality and AI simulations: Virtual Reality (VR) and AI-driven simulations could be employed to safely recreate SP-like conditions for therapeutic desensitization, neural mapping, or empathy training for clinicians.

- Public education and destigmatization campaigns: Given the high prevalence and cultural misunderstandings of SP, awareness campaigns and educational tools should be developed—especially in communities where SP is associated with fear, shame, or supernatural harm.

This study affirms the intricate interplay between the brain, genes, trauma, and culture in shaping the SP experience. Future research must move beyond reductionist models and embrace a transdisciplinary approach that humanizes, contextualizes, and demystifies this deeply subjective phenomenon.

Conclusions

This research exploration provides a comprehensive and multidimensional analysis of Sleep Paralysis (SP), framing it not merely as a transient sleep disorder but as a complex neurophysiological and psychosocial condition. The convergence of neurobiological, psychological, genetic, and cultural factors in SP underscores the need for an interdisciplinary framework in both its understanding and clinical management. Central to its pathophysiology is the persistence of REM-related muscle atonia into conscious awareness, modulated by dysregulation in brain structures such as the amygdala and parietal cortex. These mechanisms account for the vivid hallucinations, intense fear responses, and somatosensory distortions experienced during episodes.

Furthermore, the findings affirm the role of psychiatric comorbidities—especially PTSD, anxiety, and depression—in exacerbating SP experiences, likely through disrupted REM cycles and heightened emotional reactivity. Genetic studies implicating circadian rhythm-related and neurotransmitter-regulating genes point to a potential heritable component, with environmental stressors serving as triggers. Cultural and spiritual interpretations, while varying globally, play a significant role in shaping individual perceptions of SP and influence help-seeking behaviors and coping strategies.

The study’s novelty lies in its integrative perspective—connecting neurobiology with sociocultural context—and its emphasis on the importance of culturally informed clinical interventions. This holistic view challenges the dominance of purely biomedical explanations and opens the door for more personalized, culturally responsive, and trauma-informed care approaches.

Limitations of the current work include the reliance on secondary data and the absence of empirical clinical trials or neuroimaging studies. Future research should prioritize longitudinal and neurobiological investigations, explore brain connectivity during SP episodes, and develop targeted therapies that integrate psychological counseling, pharmacological support, and culturally adapted education programs.

Ultimately, addressing SP effectively requires moving beyond reductionist approaches and embracing a nuanced, patient-centered strategy that recognizes the interplay between brain, mind, and culture.

Such an approach promises to reduce stigma, improve quality of life for sufferers, and inform broader understandings of consciousness and sleep-related phenomena.

Abbreviation

SP: Sleep Paralysis; REM: Rapid Eye Movement; PTSD: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder; DNA: Deoxyribonucleic Acid; EEG: Electroencephalogram; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; fMRI: Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging; CNS: Central Nervous System; HPA Axis: Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal Axis; GxE: Gene–Environment Interaction; DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition; CBT: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy; SNP: Single Nucleotide Polymorphism; BDNF: Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor; 5-HT: 5-Hydroxytryptamine (Serotonin); GABA: Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid

Supplementary Information

The various original data sources some of which are not all publicly available, because they contain various types of private information. The available platform provided data sources that support the exploration findings and information of the research investigations are referenced where appropriate.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge and thank the GOOGLE Deep Mind Research with its associated pre-prints access platforms. This research exploration was investigated under the platform provided by GOOGLE Deep Mind which is under the support of the GOOGLE Research and the GOOGLE Research Publications within the GOOGLE Gemini platform. Using their provided platform of datasets and database associated files with digital software layouts consisting of free web access to a large collection of recorded models that are found within research access and its related open-source software distributions which is the implementation for the proposed research exploration that was undergone and set in motion. There are many data sources some of which are resourced and retrieved from a wide variety of GOOGLE service domains as well. All the data sources which have been included and retrieved for this research are identified, mentioned and referenced where appropriate.

References

2. Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders. Chest. 2014 Nov 1;146(5):1387-94.

3. Bettencourt R. The science behind sleep paralysis. President’s Writing Awards. [Mar 2024]. 2023. Available from: https://www.boisestate.edu/presidents-writing-awards/the-science-behind-sleep-paralysis/

4. About sleep. [Feb 2023]. 2022. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about/index.html https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about/index.html

5. Akhtar MS, Feng T. Detection of Sleep Paralysis by using IoT Based Device and Its Relationship Between Sleep Paralysis And Sleep Quality. EAI Endorsed Transactions on Internet of Things. 2022 Jun 1;8(30):e4.

6. Obstructive sleep apnea. [Mar 2024]. 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/obstructive-sleep-apnea/symptoms-causes/syc-20352090#:~:text=Loud%20snoring.,dry%20mouth%20or%20sore%20throat

7. Iqbal AM, Jamal SF. Essential hypertension. In:StatPearls [Internet] 2023 Jul 20. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-.

8. Insufficient sleep syndrome. [Mar 2024]. 2024. https://www.baptisthealth.com/care-services/conditions-treatments/insufficient-sleep-syndrome#:~:text=Insufficient%20sleep%20syndrome%20is%20a,spend%20enough%20time%20at%20rest

9. Wróbel-Knybel P, Flis M, Rog J, Jalal B, Karakuła-Juchnowicz H. Risk factors of sleep paralysis in a population of Polish students. BMC Psychiatry. 2022 Jun 7;22(1):383.

10. Wilson's disease. [Mar 2024]. 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/wilsons-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20353251

11. Rauf B, Perach R, Madrid‐Valero JJ, Denis D, Sharpless BA, Poerio GL, et al. The associations between paranormal beliefs and sleep variables. Journal of Sleep Research. 2023 Aug;32(4):e13810.

12. Hurd R. The Sleep Paralysis Report. [Mar 2024 ]. 2024. https://dreamstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/Sleep-Paralysis-Report-2010.pdf

13. Mainieri G, Maranci JB, Champetier P, Leu-Semenescu S, Gales A, Dodet P, et al. Are sleep paralysis and false awakenings different from REM sleep and from lucid REM sleep? A spectral EEG analysis. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2021 Apr 1;17(4):719-27.

14. Jalal B, Sevde Eskici H, Acarturk C, Hinton DE. Beliefs about sleep paralysis in Turkey: Karabasan attack. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2021 Jun;58(3):414-26.

15. Sleep demon: understanding the phenomenon. [Jul 2024]. 2022. https://www.sleepfoundation.org/parasomnias/sleep-demon

16. Bhat R, Shetty SJ, Shabaraya AR. Association Between Sleep Quality and Sleep Paralysis Among College Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Sleep. 2025;3:03.

17. Joachin C. Sleep Paralysis. Sleep. 2025 Mar 24.

18. Olunu E, Kimo R, Onigbinde EO, Akpanobong MA, Enang IE, Osanakpo M, et al. Sleep paralysis, a medical condition with a diverse cultural interpretation. International Journal of Applied and Basic Medical Research. 2018 Jul 1;8(3):137-42.

19. Hofer VS. Containing the Nightmare: A Multidisciplinary Exploration of the Sleep Paralysis Phenomenon. Master's thesis, Pacifica Graduate Institute, USA; 2025.

20. Huijzer W, Treur J. An adaptive network model for sleep paralysis: The risk factors and working mechanisms. InProceedings of the Computational Methods in Systems and Software. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. pp. 540-56.

21. Wróbel-Knybel P, Karakuła-Juchnowicz H, Flis M, Rog J, Hinton DE, Boguta P, et al. Prevalence and clinical picture of sleep paralysis in a Polish student sample. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 May;17(10):3529.

22. Khan FF, Haq MS, Ashfaq A, Saud M, Ibrahim A. Monster of the Night: Identifying Pakistani Gender-Based, Religious, and Cultural Influences on Sleep Paralysis Among University Students. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry. 2025 Jan 25:1-24.

23. Ohayon MM, Dave S, Crawford S, Swick TJ, Côté ML. Prevalence of narcolepsy in representative samples of the general population of North America, Europe, and South Korea. Psychiatry Research. 2025 Feb 13:116390.

24. Ganguly G. “Exploding head syndrome-It’s not as benign as we think, with the company it keeps”. Sleep. 2025 Feb 22:zsaf044.

25. Biscarini F, Barateau L, Pizza F, Plazzi G, Dauvilliers Y. Narcolepsy and rapid eye movement sleep. Journal of Sleep Research. 2025 Apr;34(2):e14277.

26. Raza N, Farooq A. Manifestation of Sleep Paralysis among Clinical and Non-clinical Population; a comparative study. Journal of Health and Rehabilitation Research. 2024 Feb 17;4(1):759-63.

27. Cui N, van Looij MA, Kasius KM. Successful treatment of sleep paralysis with the Sleep Position Trainer: a case report. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2022 Sep 1;18(9):2317-9.

28. Blood C, Cacciatore J. “It Started After Trauma”: The Effects of Traumatic Grief on Sleep Paralysis. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying. 2024 Sep;89(4):1451-72.

29. Sharma A, Sakhamuri S, Giddings S. Recurrent fearful isolated sleep paralysis–A distressing co-morbid condition of obstructive sleep apnea. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 2023 Mar 1;12(3):578-80.

30. Wróbel-Knybel P, Rog J, Jalal B, Szewczyk P, Karakuła-Juchnowicz H. Sleep paralysis among professional firefighters and a possible association with PTSD—Online survey-based study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2021 Sep 7;18(18):9442.

31. Ortiz LE, Morse AM, Krahn L, Lavender M, Horsnell M, Cronin D, et al. A Survey of People Living with Narcolepsy in the USA: Path to Diagnosis, Quality of Life, and Treatment Landscape from the Patient’s Perspective. CNS Drugs. 2025 Mar 20:1-14.

32. Morse AM, Kim SY, Harris S, Gow M. Narcolepsy: beyond the classic pentad. CNS Drugs. 2025 Mar 20:1-14.

33. Roth T. Therapeutic Use of γ-Hydroxybutyrate: History and Clinical Utility of Oxybates and Considerations of Once-and Twice-Nightly Dosing in Narcolepsy. CNS drugs. 2025 Mar 20:1-5.

34. Lin QW, Wei SH, Wu YX, Wei SC, Lin YQ. Electronic device usage pattern is associated with sleep disturbances in adolescents: a latent class analysis. Eur J Pediatr. 2025 Mar 11;184(4):237.

35. Sun Y, Xu T, Xu H. Safety of dual orexin receptor antagonists: a real-world pharmacovigilance study. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2025 Feb 24:1-7.

36. Varallo G, Musetti A, Filosa M, Rapelli G, Pizza F, Plazzi G, et al. Narcolepsy Beyond Medication: A Scoping Review of Psychological and Behavioral Interventions for Patients with Narcolepsy. J Clin Med. 2025 Apr 10;14(8):2608.

37. Mengmeng W, Lanbo W, Weihan W, Xiaosong D, Fang H, Spruyt K, et al. Phenotypic clusters of narcolepsy type 1: Insights from age of onset, weight gain, sleep patterns, and impulsivity. Sleep Med. 2025 Jun;130:3-12.

38. Haami D, Gibson R, Lindsay N, Tassell-Matamua N. Kei te moe te tinana, kei te oho te wairua–As the body sleeps, the spirit awakens: exploring the spiritual experiences of contemporary Māori associated with sleep. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 2025 Jan 2;20(1):116-36.

39. Akhtar ZB, Rozario VS. AI Perspectives Within Computational Neuroscience: EEG Integrations and the Human Brain. Artificial Intelligence and Applications. 2025 Mar 19;3(2):145-60.

40. Akhtar ZB. Artificial intelligence within medical diagnostics: A multi-disease perspective. Artificial Intelligence in Health. 2025 Jan 6:5173.

41. Akhtar ZB. Exploring AI for pain research management: A deep dive investigative exploration. Journal of Pain Research and Management. 2025 Jan 1;1(1):28-42.

42. Akhtar ZB, Rozario VS. The Design Approach of an Artificial Human Brain in Digitized Formulation based on Machine Learning and Neural Mapping. In: 2020 International Conference for Emerging Technology (INCET): 2020 Jun 5; Belgaum, India, 2020.

43. Martins IJ. Anti-aging genes improve appetite regulation and reverse cell senescence and apoptosis in global populations. Advances in Aging Research. 2016;5:9-26.

44. Martins IJ. Single gene inactivation with implications to diabetes and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome. Journal of Clinical Epigenetics. 2017 Aug 1;3(3):24.

45. Martins IJ. Nutrition therapy regulates caffeine metabolism with relevance to NAFLD and induction of type 3 diabetes. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2017;4(1):019.

46. Martins I. Sirtuin 1, a diagnostic protein marker and its relevance to chronic disease and therapeutic drug interventions. EC Pharmacology and Toxicology. 2018; 6(4):209-15.

47. Sharpless BA. A clinician's guide to recurrent isolated sleep paralysis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016 Jul 19;12:1761-7.

48. Denis D. Relationships between sleep paralysis and sleep quality: current insights. Nat Sci Sleep. 2018 Nov 2;10:355-67.

49. Denis D, French CC, Gregory AM. A systematic review of variables associated with sleep paralysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2018 Apr;38:141-157.

50. Mahlios J, De la Herrán-Arita AK, Mignot E. The autoimmune basis of narcolepsy. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2013 Oct;23(5):767-73.

51. Sharpless BA, Barber JP. Lifetime prevalence rates of sleep paralysis: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2011 Oct;15(5):311-5.

52. Bell CC, Hildreth CJ, Jenkins EJ, Carter C. The relationship of isolated sleep paralysis and panic disorder to hypertension. J Natl Med Assoc. 1988 Mar;80(3):289-94.

53. Mitler MM, Hajdukovic R, Erman M, Koziol JA. Narcolepsy. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1990 Jan;7(1):93-118.

54. Ali M, Auger RR, Slocumb NL, Morgenthaler TI. Idiopathic hypersomnia: clinical features and response to treatment. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009 Dec 15;5(6):562-8.

55. Anderson KN, Pilsworth S, Sharples LD, Smith IE, Shneerson JM. Idiopathic hypersomnia: a study of 77 cases. Sleep. 2007 Oct;30(10):1274-81.

56. Stores G. Sleep paralysis and hallucinosis. Behav Neurol. 1998;11(2):109-112.

57. Choi YW, Song JH, Kim TW, Kim SM, Cho IH, Hong SC. Two Cases of Narcoleptic patients with sleep paralysis as a Chief Complaint. Sleep Medicine Research. 2018 Dec 30;9(2):128-30.

58. Jalal B, Romanelli A, Hinton DE. Cultural Explanations of Sleep Paralysis in Italy: The Pandafeche Attack and Associated Supernatural Beliefs. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2015 Dec;39(4):651-64.

59. Terrillon JC, Marques-Bonham S. Does recurrent isolated sleep paralysis involve more than cognitive neurosciences. Journal of Scientific Exploration. 2001;15(1):97-123.

60. Takeuchi T, Fukuda K, Sasaki Y, Inugami M, Murphy TI. Factors related to the occurrence of isolated sleep paralysis elicited during a multi-phasic sleep-wake schedule. Sleep. 2002 Feb 1;25(1):89-96