Abstract

Photoacoustic imaging has increasing biomedical applications, from fundamental research to clinical translations, due to its high optical absorption contrast and high acoustic resolution in deep tissue. The current implementations of photoacoustic imaging employ either a multi-element ultrasonic array for parallel signal detection or raster-scanning of a single-element detector for serial data acquisition, demanding a trade-off between throughput and cost. Recently a new photoacoustic imaging method–photoacoustic topography through an ergodic relay (PATER) has been developed to address this issue. PATER can provide snapshot wide-field images upon single laser shots with just one single-element detector. Till now, PATER has demonstrated in vivo high-speed monitoring of changes in oxygen saturation and fast matching of vascular patterns for biometric authentication. PATER has achieved high-throughput imaging over a large field of view with a much-simplified and miniaturized configuration. This offers an economical alternative to the array-based parallel imaging system and promises wearable photoacoustic monitoring of human vital signs.

Keywords

Photoacoustic topography, Ergodic relay, Snapshot imaging, High-throughput imaging

Abbreviations

PAT: Photoacoustic Tomography; PACT: Photoacoustic Computed Tomography; PAM: Photoacoustic Microscopy; PATER: Photoacoustic Topography through an Ergodic Relay; ER: Ergodic Relay; FOV: Field-of-view

Introduction

Photoacoustic imaging or photoacoustic tomography (PAT), also known as optoacoustic tomography, is an emerging hybrid imaging modality that combines the advantages of both optical and ultrasonic imaging. It inherits the high optical contrast from optical imaging and offers high spatial resolution in deep tissue based on its acoustic detection [1,2]. Photoacoustic signals are produced by illuminating a tissue of interest with short laser pulses (typically in ~ns). Some molecules within the tissue absorb the incident photons regardless scattered or not and convert the light energy into acoustic waves, also called PA waves. Ultrasonic transducers measure the Photoacoustic (PA) waves, and digital reconstruction yields images that map optical absorption inside the tissue. As biological tissues scatter incident photons heavily, conventional optical imaging cannot provide high-resolution imaging in deep tissue. By converting photons into phonons and detecting the acoustic waves for image formation, PAT offers superior spatial resolution at depths inside the tissue. Moreover, by tuning the excitation wavelengths to match the optical absorption signatures of the molecules to be imaged, PAT has imaged hemoglobin [3-6], melanin [7,8], DNA/RNA [9,10], lipid [11-13], myoglobin [14], organic dyes [15,16], nanoparticles [17-23], and genetically encoded proteins [24-29] with high contrast.

PAT has two major incarnations–photoacoustic computed tomography (PACT) and photoacoustic microscopy (PAM) based on their signal detection and image formation methods [30-32]. In PAM, the generated PA signals are detected by raster scanning of a single-element ultrasonic transducer for serial acquisition [33,34]. While PACT employs multi-element transducer arrays to detect the PA waves in parallel [35,36]. In the former case, point-by-point mechanical scanning limits the imaging throughput. In the latter case, multi-element transducer arrays with multi-channel amplifiers and digitizers significantly increase the system’s complexity, cost, and size. PAT urgently demands a new implementation using a much-simplified setup with high throughput. Recently, photoacoustic topography through an ergodic relay (PATER) has been developed to offer high-throughput snapshot wide-field imaging with a single element detector [37,38]. PATER demonstrated a snapshot wide-field imaging with a frame rate up to 2 kHz. Taking advantage of such high imaging speed, PATER directly visualized blood oxygen level changes in the mouse brain and achieved fast biometric authentication by matching vascular patterns [39].

Principle of PATER

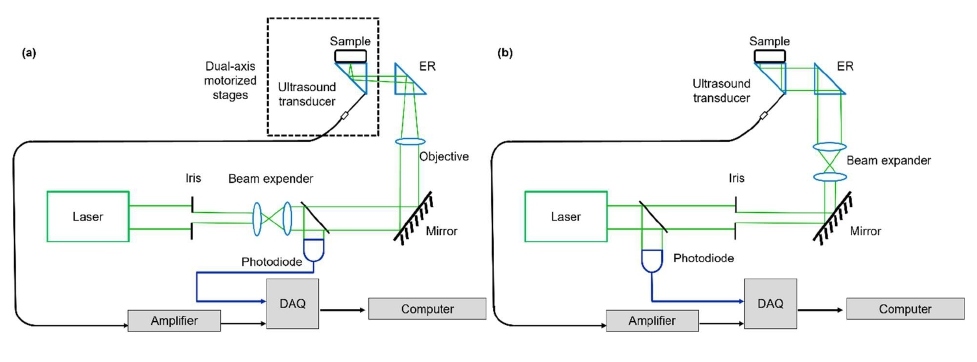

The key component of PATER is the ergodic relay (ER), an acoustic waveguide that encodes acoustic waves from the input points to an output point with distinct amplitudes and time of flight. Previous studies have shown that a right-angle optical prism can serve as an ER for PATER [37,38]. PATER requires two acquisition steps: calibration and wide-field imaging, as shown in Figure 1. During calibration, a focused laser beam is used to scan across the entire field-of-view (FOV) of the object (Figure 1a). The laser pulse width (~5 ns) is much narrower than the central period of the ultrasonic transducer (~100 ns), and the focused beam diameter (~10 µm) is much smaller than the central acoustic wavelength (~600 µm), then each PA wave excited by the focused laser pulse can be treated as a spatiotemporal delta function of the whole system. Thus, the system impulse response at each pixel can be calibrated by raster scanning the laser beam over the FOV, and the system matrix K can be obtained. During wide-field imaging, a broad beam uniformly illuminates the object (Figure 1b). The PA signals from all pixels of the entire illumination volume, denoted as s , are acquired in parallel using only a single-element ultrasonic detector, permitting snapshot wide-field imaging. The wide-field measurement can be expressed as

s= KP (1)

Figure 1: The principle of PATER. (a) In the calibration step, light is tightly focused on the imaging surface of the ER and scanned across the entire FOV to acquire the impulse responses of the system. (b) The wide-field imaging step, where a broad laser light uniformly is shined on the object and repeated for high-speed wide-field imaging.

where P is the wide-field images, which can be reconstructed by solving the inverse problem of Equation 1. The reconstructed wide-field images map the optical absorption changes of the object. With a high-repetition-rate laser for broad illumination, PATER provides snapshot imaging and captures fast dynamics with a sub-millisecond temporal resolution over a large FOV.

Biomedical Applications of High-throughput PATER

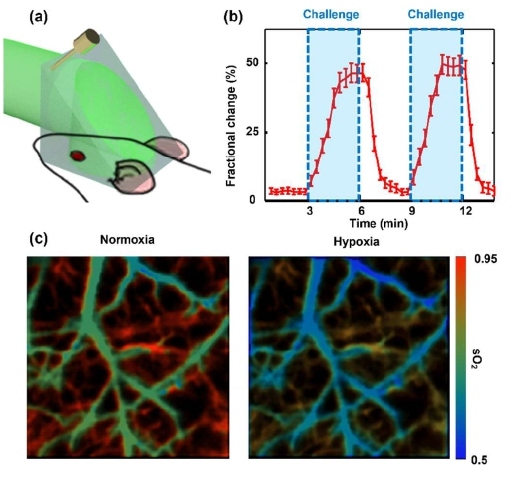

High-speed monitoring of blood oxygen changes in the brain

Inside our body, the hemoglobin within red blood cells binds with oxygen and carries it through the bloodstream to support cellular activities. It is crucial to monitor the blood oxygen level as it is a vital sign. To demonstrate the snapshot wide-field imaging, PATER first imaged the changes in blood oxygen saturation (sO2) in a mouse brain in vivo [39]. As a demonstration, sO2 inside the mouse brain was artificially altered via oxygen challenges, where oxygen concentration of inhalation gas supplied to the mouse was manipulated. Initially, the mouse inhaled a mixture of 95% oxygen and 5% nitrogen. After calibration, the mouse brain vasculature was first imaged with a broad laser illumination at 620 nm through the intact skull (Figure 2a). During the oxygen challenge, a mixture of 5% oxygen and 95% nitrogen was supplied to the mouse for 3 minutes. Then the inhalation gas mixture was then changed back to the initial concentration. The time course of the PA signals during the oxygen challenges was shown in Figure 2b. Upon two different wavelengths (532 nm and 620 nm) illumination, the sO2 map of the cortical vessels was also imaged before (normoxia) and after (hypoxia) the oxygen challenges, as shown in Figure 2c. Due to the simplified system configuration and high-throughput, PATER offers an alternative solution to pulse oximeters, which provide only the averaged sO2 level of the arteries. In contrast, PATER can yield real-time images of the sO2 distribution of a blood vessel network.

Figure 2: High-speed imaging of sO2 changes in a mouse brain. (a) Wide-field imaging of the mouse brain. (b) Time course of fractional signal changes during oxygen challenge. (c) Wide-field images of sO2 in the cortical vessels before (normoxia) and after (hypoxia) the challenge.

Fast matching of vascular patterns in vivo

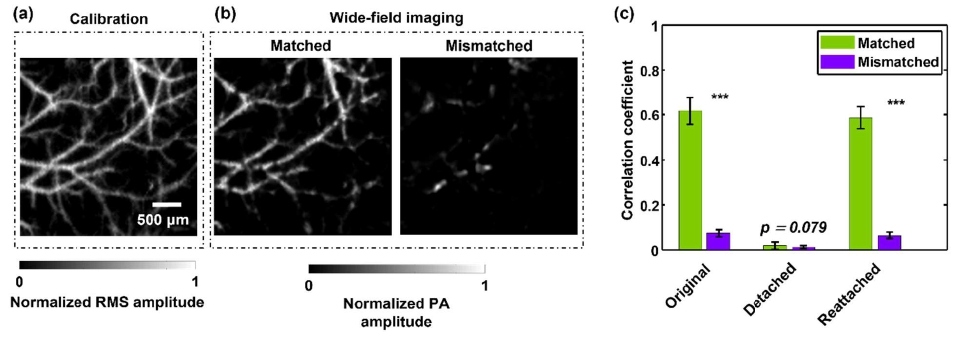

Biometric authentication that employs unique biological characteristics of individuals to verify their identities is widely used in our daily life. Under-the-skin biological characteristics, such as vascular patterns, are more secure and reliable in identifying an individual than surface characteristics such as fingerprints. Because they are not directly exposed and contain in vivo physiological features—such as blood flow and oxygenation—that cannot be readily replicated by others. Biometric authentication based on under-the-skin biological characteristics hold great promise; however, they require high-speed processing and high accuracy for reliable usage. To demonstrate the capability of fast and reliable biometric authentication, PATER achieved fast differentiation of vascular patterns.

During the demonstration, one mouse was mounted in a stereotaxic frame, and the cortical vasculature was imaged in calibration mode (Figure 3a). During the wide-field imaging, the mouse was first detached from the ER, then reattached to the same position. The same procedure was repeated for a second mouse. The wide-field images of the first mouse’s vasculature were reconstructed using the calibration data of both itself and the second mouse. As a result, the wide-field image reconstructed from the calibration data of itself (matched) recovered the original vasculature, while the wide-field image reconstructed from the calibration data of the second mouse (mismatched) revealed no visible features (Figure 3b). The correlation coefficients between the calibration images and the wide-field reconstruction images were calculated, as shown in Figure 3c. The wide-field images reconstructed with the matched calibration data show much higher correlation than those reconstructed from the mismatched calibration data. The vasculature is also recovered after being repositioned to the ER.

Figure 3: Fast vascular recognition in mice. (a) Calibration image of brain vasculatures from a mouse. (b) Wide-field images of the mouse vasculature, reconstructed using the calibration data of itself (matched) and a different mouse (mismatched), respectively. (c) Correlation between the wide-field images and the calibration images of itself and a different mouse. The mouse was detached from and reattached to the ER to demonstrate the repeatability of reconstruction.

Conclusions

The small size, low cost, and simplified system setup of PATER make it a feasible solution for portable applications, such as a wearable device to monitor vital signs in patients. Moreover, PATER can both identify vessel patterns and quantify functional dynamics with high throughput, and it promises comprehensive, secure, and robust biometric authentication.

References

2. Ntziachristos V. Going deeper than microscopy: the optical imaging frontier in biology. Nature Methods. 2010 Aug;7(8):603-14.

3. Hsu HC, Li L, Yao J, Wong TT, Shi J, Chen R, et al. Dual-axis illumination for virtually augmenting the detection view of optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2018 Jul;23(7):076001.

4. Zhang P, Li L, Lin L, Hu P, Shi J, He Y, et al. High‐resolution deep functional imaging of the whole mouse brain by photoacoustic computed tomography in vivo. Journal of Biophotonics. 2018 Jan;11(1):e201700024.

5. Maneas E, Aughwane R, Huynh N, Xia W, Ansari R, Kuniyil Ajith Singh M, et al. Photoacoustic imaging of the human placental vasculature. Journal of Biophotonics. 2020 Apr;13(4):e201900167.

6. Liu YH, Brunner LM, Rebling J, Greenwald MB, Werner S, Detmar M, et al. Non-invasive longitudinal imaging of VEGF-induced microvascular alterations in skin wounds. Theranostics. 2022;12(2):558.

7. He Y, Wang L, Shi J, Yao J, Li L, Zhang R, et al. In vivo label-free photoacoustic flow cytography and on-the-spot laser killing of single circulating melanoma cells. Scientific Reports. 2016 Dec 21;6(1):1-8.

8. He H, Schönmann C, Schwarz M, Hindelang B, Berezhnoi A, Steimle-Grauer SA, et al. Fast raster-scan optoacoustic mesoscopy enables assessment of human melanoma microvasculature in vivo. Nature Communications. 2022 May 19;13(1):1-0.

9. Imai T, Shi J, Wong TT, Li L, Zhu L, Wang LV. High-throughput ultraviolet photoacoustic microscopy with multifocal excitation. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2018 Mar;23(3):036007.

10. Shi J, Wong TT, He Y, Li L, Zhang R, Yung CS, et al. High-resolution, high-contrast mid-infrared imaging of fresh biological samples with ultraviolet-localized photoacoustic microscopy. Nature Photonics. 2019 Sep;13(9):609-15.

11. Li L, Xia J, Li G, Garcia-Uribe A, Sheng Q, Anastasio MA, et al. Label-free photoacoustic tomography of whole mouse brain structures ex vivo. Neurophotonics. 2016 Jul;3(3):035001.

12. Visscher M, Pleitez MA, Van Gaalen K, Nieuwenhuizen-Bakker IM, Ntziachristos V, Van Soest G. Label-free analytic histology of carotid atherosclerosis by mid-infrared optoacoustic microscopy. Photoacoustics. 2022 Jun 1;26:100354.

13. Karlas A, Kallmayer M, Bariotakis M, Fasoula NA, Liapis E, Hyafil F, et al. Multispectral optoacoustic tomography of lipid and hemoglobin contrast in human carotid atherosclerosis. Photoacoustics. 2021 Sep 1;23:100283.

14. Lin L, Yao J, Li L, Wang LV. In vivo photoacoustic tomography of myoglobin oxygen saturation. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2015 Dec;21(6):061002.

15. Rao B, Zhang R, Li L, Shao JY, Wang LV. Photoacoustic imaging of voltage responses beyond the optical diffusion limit. Scientific Reports. 2017 May 31;7(1):1-0.

16. Zhang P, Li L, Lin L, Shi J, Wang LV. In vivo superresolution photoacoustic computed tomography by localization of single dyed droplets. Light: Science & Applications. 2019 Apr 3;8(1):1-9.

17. Li L, Patil D, Petruncio G, Harnden KK, Somasekharan JV, Paige M, et al. Integration of multitargeted polymer-based contrast agents with photoacoustic computed tomography: an imaging technique to visualize Breast Cancer Intratumor Heterogeneity. ACS Nano. 2021 Jan 19;15(2):2413-27.

18. Zhou M, Li L, Yao J, Bouchard RR, Wang L, Li C. Nanoparticles for photoacoustic imaging of vasculature. InDesign and Applications of Nanoparticles in Biomedical Imaging 2017 (pp. 337-356). Springer, Cham.

19. Li L, Yao J, Wang LV. Photoacoustic tomography enhanced by nanoparticles. Wiley Encyclopedia of Electrical and Electronics Engineering. 2016:1-4.

20. Wu Z, Li L, Yang Y, Hu P, Li Y, Yang SY, et al. A microrobotic system guided by photoacoustic computed tomography for targeted navigation in intestines in vivo. Science Robotics. 2019 Jul 24;4(32):eaax0613.

21. Liu N, Gujrati V, Malekzadeh-Najafabadi J, Werner JP, Klemm U, Tang L, et al. Croconaine-based nanoparticles enable efficient optoacoustic imaging of murine brain tumors. Photoacoustics. 2021 Jun 1;22:100263.

22. Wrede P, Degtyaruk O, Kalva SK, Deán-Ben XL, Bozuyuk U, Aghakhani A, et al. Real-time 3D optoacoustic tracking of cell-sized magnetic microrobots circulating in the mouse brain vasculature. Science Advances. 2022 May 11;8(19):eabm9132.

23. Kalva SK, Sánchez-Iglesias A, Deán-Ben XL, Liz-Marzán LM, Razansky D. Rapid Volumetric Optoacoustic Tracking of Nanoparticle Kinetics across Murine Organs. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 2021 Dec 24;14(1):172-8.

24. Li L, Hsu HC, Verkhusha VV, Wang LV, Shcherbakova DM. Multiscale Photoacoustic Tomography of a Genetically Encoded Near‐Infrared FRET Biosensor. Advanced Science. 2021 Nov;8(21):2102474.

25. Li L, Shemetov AA, Baloban M, Hu P, Zhu L, Shcherbakova DM, et al. Small near-infrared photochromic protein for photoacoustic multi-contrast imaging and detection of protein interactions in vivo. Nature Communications. 2018 Jul 16;9(1):1-4.

26. Yao J, Kaberniuk AA, Li L, Shcherbakova DM, Zhang R, Wang L, et al. Multiscale photoacoustic tomography using reversibly switchable bacterial phytochrome as a near-infrared photochromic probe. Nature Methods. 2016 Jan;13(1):67-73.

27. Vonk J, Kukačka J, Steinkamp PJ, de Wit JG, Voskuil FJ, Hooghiemstra WT, et al. Multispectral optoacoustic tomography for in vivo detection of lymph node metastases in oral cancer patients using an EGFR-targeted contrast agent and intrinsic tissue contrast: A proof-of-concept study. Photoacoustics. 2022 Jun 1;26:100362.

28. Mishra K, Fuenzalida-Werner JP, Pennacchietti F, Janowski R, Chmyrov A, Huang Y, et al. Genetically encoded photo-switchable molecular sensors for optoacoustic and super-resolution imaging. Nature Biotechnology. 2022 Apr;40(4):598-605.

29. Qian Y, Piatkevich KD, Mc Larney B, Abdelfattah AS, Mehta S, Murdock MH, et al. A genetically encoded near-infrared fluorescent calcium ion indicator. Nature Methods. 2019 Feb;16(2):171-4.

30. Li L, Zhu L, Ma C, Lin L, Yao J, Wang L, et al. Single-impulse panoramic photoacoustic computed tomography of small-animal whole-body dynamics at high spatiotemporal resolution. Nature Biomedical Engineering. 2017 May 10;1(5):1-1.

31. Yao J, Wang L, Yang JM, Maslov KI, Wong TT, Li L, et al. High-speed label-free functional photoacoustic microscopy of mouse brain in action. Nature Methods. 2015 May;12(5):407-10.

32. Manohar S, Razansky D. Photoacoustics: a historical review. Advances in Optics and Photonics. 2016 Dec 31;8(4):586-617.

33. Zhu L, Li L, Gao L, Wang LV. Multiview optical resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Optica. 2014 Oct 20;1(4):217-22.

34. Li L, Yeh C, Hu S, Wang L, Soetikno BT, Chen R, et al. Fully motorized optical-resolution photoacoustic microscopy. Optics Letters. 2014 Apr 1;39(7):2117-20.

35. Li G, Li L, Zhu L, Xia J, Wang LV. Multiview Hilbert transformation for full-view photoacoustic computed tomography using a linear array. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2015 Jun;20(6):066010.

36. Li L, Zhu L, Shen Y, Wang LV. Multiview Hilbert transformation in full-ring transducer array-based photoacoustic computed tomography. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2017 Jul;22(7):076017.

37. Li Y, Li L, Zhu L, Maslov K, Shi J, Hu P, et al. Snapshot photoacoustic topography through an ergodic relay for high-throughput imaging of optical absorption. Nature Photonics. 2020 Mar;14(3):164-70.

38. Li L, Li Y, Zhang Y, Wang LV. Snapshot photoacoustic topography through an ergodic relay of optical absorption in vivo. Nature Protocols. 2021 May;16(5):2381-94.

39. Li Y, Li L, Zhu L, Shi J, Maslov K, Wang LV. Photoacoustic topography through an ergodic relay for functional imaging and biometric application in vivo. Journal of Biomedical Optics. 2020 Jul;25(7):070501.