Abstract

Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors are widely used in the management of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) and other B-cell malignancies. Despite their therapeutic efficacy, BTK inhibitors are associated with cardiac toxicities, most notably atrial fibrillation and hypertension. However, our recent case series highlights the rare yet underappreciated risk of pericarditis and cardiac tamponade in patients treated with both first- and second-generation BTK inhibitors. This article highlights the need for vigilance in clinical practice and the importance of timely echocardiography. The challenges of early diagnosis are discussed, as well as the role of emerging technologies, such as point-of-care ultrasound and AI-based diagnostics. Ultimately, a cautious, informed approach is crucial to balance the benefits of BTK therapy with the risk of rare but life-threatening cardiac events.

Commentary

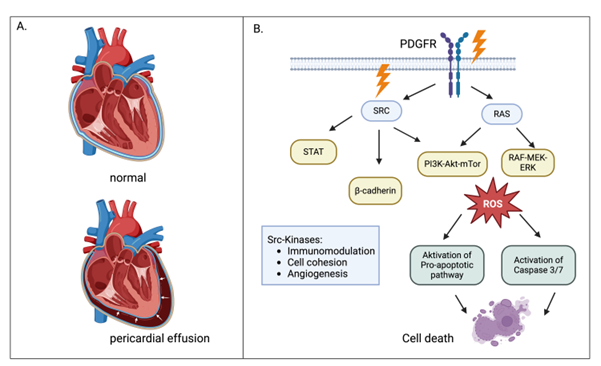

Nearly a decade since the introduction of first-generation Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors in the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL), their use has expanded with the second-generation agents zanubrutinib and acalabrutinib. These agents show high efficacy particularly in patients with TP53 mutations or del(17p) [1,2]. While cardiac risks of BTK inhibitors, such as atrial fibrillation (AF) and hypertension, are relatively well known, our recent case series highlights an underappreciated risk: pericarditis and cardiac tamponade. In our case series, we presented three patients treated with BTK inhibitors: two on ibrutinib (for CLL and Waldenström's macroglobulinemia) and one on the second-generation BTK inhibitor zanubrutinib (for CLL) [3]. All three developed pericarditis and pericardial effusions. Two patients progressed to cardiac tamponade with cardiogenic shock, necessitating emergency pericardial decompression. Notably, two patients were anticoagulated for atrial fibrillation, which can increase the risk of haemopericardium [4]. However, the fluid in all cases was serous or serosanguineous, and not frank blood, suggesting anticoagulation alone was unlikely the cause for the effusion. This is further corroborated by MRI findings which showed acute inflammation, with inflammatory cells and no malignant cells in the pericardial fluid. Pericardial effusions have been reported through the FDA Adverse Events Reporting System (FAERS) as the 6th most common cardiac toxicity for ibrutinib, with 485 reports recorded between 2014 - 2024. In contrast, atrial fibrillation is the most common cardiac toxicity with over 3,400 reports. While the incidence of pericardial effusions may be lower than other cardiac complications, the risk to patients is still significant. Cardiac tamponade can develop and progress rapidly to life-threatening cardiogenic shock [5]. The establishment of pericarditis and pericardial effusions with BTK inhibitors is multifactorial and not fully understood. One well-known mechanism is the 'aspirin-like' effect on GPVI-dependent platelet aggregation and the inhibition of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), which impairs cardiac myocyte function. This way, anticoagulants like aspirin or DOACs used for AF can exacerbate blood accumulation in the pericardial cavity [6]. The majority of effusions is not haemorrhagic but serosanguinous in nature and associated with pericardial inflammation. Thus, other mechanisms must be at play. The most important mechanisms probably involve off-target inhibition of tyrosine kinases. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) are potent anti-cancer therapies targeting pathways that regulate cellular proliferation and tumor angiogenesis. The human genome encodes for approximately ninety TKs. Ibrutinib with its multi-kinase activity has off target effects on platelet derived growth factor receptor β (PDGFR-β) and on Src family tyrosine kinases [7]. The Scr family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases are key regulators of multiple signaling pathways, including those involved in cell proliferation, migration and adhesion. Downregulation of downstream pathways leads to oxidative stress and activation of pro-apoptotic pathways which result in inflammation and cell death on one hand side, and disruption of epithelial cohesion on the other side [8]. Second-generation BTK inhibitors with more selective targeting, such as zanubrutinib, naturally show reduced cardiotoxicity. The ALPINE trial showed a nearly 50% reduction in AF and hypertension compared to ibrutinib with no cases of pericardial tamponade reported [1]. Although our case series is small, it includes the first documented case of a patient developing pericarditis and cardiac tamponade on zanubrutinib. This suggests that while pericardial tamponade events with second-generation BTK inhibitors are indeed rare, they can still occur. The central question is: How can we as practising haematologists manage the risk in our patients? Current American, British and European best practice guidelines provide recommendations in regard to atrial fibrillation, hypertension and congestive cardiac failure, but do not recommend specific risk assessment or follow up arrangements to detect pericarditis or pericardial effusions [9-11]. In general, patients with a history of hypertension, atrial fibrillation (AF), diabetes mellitus, heart failure, cardiomyopathy, or severe valvular heart disease are considered at a particularly higher risk of developing cardiotoxicity when treated with BTK inhibitors [12]. Initiation of BTK inhibitors should be carefully balanced in these patients and venetoclax based therapy could be more appropriate. However, there is currently insufficient data to guide risk prediction for pericardial disease risk. The crucial question therefore is, is whether earlier detection would allow earlier intervention and whether this would translate into reduced mortality. During treatment monitoring, in the event of suspected cardiotoxicity, guidelines recommend pausing of BTK inhibitor, urgent echocardiography and referral to cardio-oncologists [11]. However, in practice, detecting impeding cardiac tamponade can be challenging. Patients may present with non-specific features of pericarditis, including chest pain or fever. The most common symptom of pre-tamponade in the early stages is breathlessness (64%) which is also non-specific [13]. Patient who progress to tamponade present with fatigue, breathlessness, raised jugular venous pressure (JVP), peripheral oedema and hypotension. The classical syndrome is termed the Beck’s Triad (hypotension, increased JVP, and distant heart sounds). This constellation of symptoms was first described in 1935 when tuberculosis and cardiac injuries were the most common causes of tamponade. A more sensitive clinical sign is pulsus paradoxus which can be detected in up to 98% of tamponade [14]. Pulsus paradoxus is an unfortunate misnomer, because it describes neither a pulse characteristic nor is it paradoxical. What’s more, it is both non-specific and difficult to measure, even for experienced clinicians [15]. Biomarkers such as troponin I and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) are commonly assessed to detect myocardial injury. A small study found that suppressed BNP levels (<250pg/mL) was predictive of malignant pericardial effusions [16]. However, to our knowledge no study has addressed dynamics of cardiac biomarkers in TKI induced pericardial disease. In contrast, to clinical examination and biomarkers, modern echocardiography has a sensitivity of 96% and specificity of 98% for detecting pericardial fluid. The key to successful diagnosis thus lies in prompt referral for echocardiography. It has been hypothesised, that using point-of-care echocardiography by non-cardiologists as bed-side test to 'augment' the clinical exam can identify patients with possible tamponade upfront, thereby reducing time to intervention. There is evidence that this approach may be feasible [15,17]. In a study by Bustam et al., nine emergency medicine trainees completed a web-based learning module and 3hrs practical training to estimate left ventricular function, detection of pericardial effusion and to perform basic measurements of IVC diameter. The trainees detected pericardial effusions with a sensitivity of 60%, specificity of 100%, positive predictive value of 100% and negative predictive value of 97.9% [18]. Several small studies have shown that with point-of-care echocardiography, the time to intervention can indeed be significantly reduced. For example, Alpert et al. reported a reduction in time to intervention from 70.2 hours to 11.3 hours [13]. Hanson et al. reported a reduction in the to pericardiocentesis from >48 hrs to 28.1 hrs. [13]. A similar result was seen in a study by Hoch et al., which included a larger number of patients (137 point of care vs 120 standard) and adjusted results for various confounding factors, and found that point of care was associated with earlier intervention (hazard ratio 2.08, 95% confidence interval) but not with a difference in 28-day mortality [19]. Driven by advances in ultrasound technologies, ultrasound systems are also becoming cheaper, smaller and more accessible [20]. Moreover, artificial intelligence could help to automate the process. In a recent study Potter et al. trained a deep learning model on ultrasound images from 37 cases with pericardial effusions and 39 negative controls and found the model achieved 92% specificity and 89% sensitivity in identifying pericardial effusions.

Figure 1: (A) Accumulation of fluid in the pericardial sac compromises ventricular expansion. This reduces pre-load and reduces stroke volumes. As cardiac output declines, blood pressure drops and, if cardiac output is insufficient to meet metabolic demands, cardiac shock develops. Meanwhile, the compression of the right atrium and ventricles causes backpressure in the systemic veins leading to elevated central venous pressure, which manifests as jugular venous distension. (B) Src are key regulators of multiple signalling pathways, including those involved in cell proliferation, migration, and adhesion. Inhibition of Src kinases can impair endothelial cell function, potentially increasing vascular permeability. Increased permeability of blood vessels can allow fluid to leak into surrounding tissues, including the pericardial sac, leading to effusion. PDGFR is a receptor tyrosine kinase that is primarily involved in regulating cell growth, survival, and migration, particularly in vascular smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts. It is often activated in cancer and fibrotic diseases, where it promotes tissue remodelling and angiogenesis. PDGFR inhibition can impair fibroblast-mediated tissue repair and remodelling, making the pericardium more susceptible to chronic effusion or pericarditis.

At present, available studies supporting the widespread use of point-of-care echocardiography by non-cardiologists are limited by small size, single centre and retrospective design. Also, in most studies, emergency department physicians have carried out point of care ultrasound and not haemato-oncologists. Further research is needed to explore the value of point of care echocardiography for the acute oncology practice and more crucially, to demonstrate that the reduced time to intervention also results in reduced mortality. In conclusion, while the incidence of pericarditis and cardiac tamponade in patients treated with BTK inhibitors is very low, the potential for these life-threatening complications warrants vigilance by prescribers. Our case series underscored the need for a proactive approach in monitoring and managing these patients, particularly those with additional cardiovascular risk factors. Regular symptom assessments and timely use of echocardiography are crucial for early detection. Ultimately, balancing the therapeutic benefits of BTK inhibitors with a keen awareness of their risks is essential for optimising patient outcomes.

References

2. Sharman JP, Egyed M, Jurczak W, Skarbnik A, Pagel JM, Flinn IW, et al. Acalabrutinib with or without obinutuzumab versus chlorambucil and obinutuzmab for treatment-naive chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (ELEVATE TN): a randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020 Apr 18;395(10232):1278-91. Erratum in: Lancet. 2020 May 30;395(10238):1694.

3. Erblich T, Manisty C, Gribben J. Pericarditis and Cardiac Tamponade in Patients Treated with First and Second Generation Bruton Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors: An Underappreciated Risk. Case Rep Hematol. 2024 Jul 9;2024:2312182.

4. Asad ZUA, Ijaz SH, Chaudhary AMD, Khan SU, Pakala A. Hemorrhagic Cardiac Tamponade Associated with Apixaban: A Case Report and Systematic Review of Literature. Cardiovasc Revasc Med. 2019 Nov;20(11S):15-20.

5. Allouchery M, Tomowiak C, Lombard T, Pérault-Pochat MC, Salvo F. Safety Profile of Ibrutinib: An Analysis of the WHO Pharmacovigilance Database. Front Pharmacol. 2021 Oct 28;12:769315.

6. Miatech JL, Hughes JH, McCarty DK, Stagg MP. Ibrutinib-Associated Cardiac Tamponade with Concurrent Antiplatelet Therapy. Case Rep Hematol. 2020 Mar 27;2020:4282486.

7. Kelly K, Swords R, Mahalingam D, Padmanabhan S, Giles FJ. Serosal inflammation (pleural and pericardial effusions) related to tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Target Oncol. 2009 Apr;4(2):99-105.

8. Shyam Sunder S, Sharma UC, Pokharel S. Adverse effects of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy: pathophysiology, mechanisms and clinical management. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023 Jul 7;8(1):262.

9. Awan FT, Addison D, Alfraih F, Baratta SJ, Campos RN, Cugliari MS, et al. International consensus statement on the management of cardiovascular risk of Bruton's tyrosine kinase inhibitors in CLL. Blood Adv. 2022 Sep 27;6(18):5516-25.

10. Tang CPS, Lip GYH, McCormack T, Lyon AR, Hillmen P, Iyengar S, et al; BSH guidelines committee, UK CLL Forum. Management of cardiovascular complications of bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Br J Haematol. 2022 Jan;196(1):70-8.

11. Poku N, Ramalingam S, Andres MS, Gevaert S, Lyon AR. Monitoring and treatment of cardiovascular complications during cancer therapies. Part II: Tyrosine kinase inhibitors. [cited 14 Oct 2024]. Available: https://www.escardio.org/Councils/Council-for-Cardiology-Practice-(CCP)/Cardiopractice/monitoring-and-treatment-of-cardiovascular-complications-during-cancer-therapies-Part-2

12. Barr PM, Owen C, Robak T, Tedeschi A, Bairey O, Burger JA, et al. Up to 8-year follow-up from RESONATE-2: first-line ibrutinib treatment for patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood Adv. 2022 Jun 14;6(11):3440-50.

13. Hanson MG, Chan B. The role of point-of-care ultrasound in the diagnosis of pericardial effusion: a single academic center retrospective study. Ultrasound J. 2021 Feb 4;13(1):2.

14. Guberman BA, Fowler NO, Engel PJ, Gueron M, Allen JM. Cardiac tamponade in medical patients. Circulation. 1981 Sep;64(3):633-40.

15. Jay GD, Onuma K, Davis R, Chen MH, Mansell A, Steele D. Analysis of physician ability in the measurement of pulsus paradoxus by sphygmomanometry. Chest. 2000 Aug;118(2):348-52.

16. Carasso S, Grosman-Rimon L, Nassar A, Kusniec F, Ghanim D, Elbaz-Greener G, et al. Serum BNP levels are associated with malignant pericardial effusion. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2019 Apr 9;23:100359.

17. Allimant P, Guillo L, Fierling T, Rabiaza A, Cibois-Honnorat I. Point-of-care ultrasound to assess left ventricular ejection fraction in heart failure in unselected patients in primary care: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2024 Aug 20:cmae040.

18. Bustam A, Noor Azhar M, Singh Veriah R, Arumugam K, Loch A. Performance of emergency physicians in point-of-care echocardiography following limited training. Emerg Med J. 2014 May;31(5):369-73.

19. Hoch VC, Abdel-Hamid M, Liu J, Hall AE, Theyyunni N, Fung CM. ED point-of-care ultrasonography is associated with earlier drainage of pericardial effusion: A retrospective cohort study. Am J Emerg Med. 2022 Oct;60:156-63.

20. Merkel D, Lueders C, Schneider C, Yousefzada M, Ruppert J, Weimer A, et al. Prospective Comparison of Nine Different Handheld Ultrasound (HHUS) Devices by Ultrasound Experts with Regard to B-Scan Quality, Device Handling and Software in Abdominal Sonography. Diagnostics (Basel). 2024 Aug 30;14(17):1913.