Abstract

Gastric marginal zone lymphoma (gMZBL) is the most frequent type of extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT). The histology of gMZBL shows typical small cell morphology, however, there also exists a large cell variant. Additionally, composite lymphomas (ComL) harboring both, the small-cell and large-cell morphology can occur; therefore, ComL is an example of lymphoma progression. However, the WHO currently defines the large cell variant of gMZBL as a “diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in the presence of accompanying MALT lymphoma”. In this mini review we summarize morphological and immunohistochemical aspects including molecular cytogenetic data as well as RNA expression and methylation data of gMZBL and provide evidence that the large cell variant of gMZBL is a lymphoma distinct from conventional DLBCL.

Keywords

Gastric marginal zone lymphoma, Lymphoma progression, Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma

Introduction

Gastric marginal zone lymphoma (gMZBL) is the most frequent type of extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) (ICD-O code: 9699/3). The histology of gMZBL shows typical small cell morphology, however, there also exists a large cell variant. Additionally, composite lymphomas (ComL) harboring both, the small-cell and large-cell morphology can occur. We and others have shown that ComL is a coexistence of the small cell and the large cell variant where both are clonally related. Thus, ComL features lymphoma progression. However, the WHO currently defines the large cell variant of gMZBL as a “diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) in the presence of accompanying MALT lymphoma” [1]. Gastric marginal zone lymphoma is often connected to the infection by Helicobacter pylori (H.p.) that per se causes local emergence of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) through chronic inflammation. In this setting gMZBL may occur [2]. The eradication of H.p. has been repeatedly shown to be followed by the complete remission of gMZBL and eventually also to regression of the large cell variant [3,4].

In this mini review we summarize morphological and immunohistochemical aspects including molecular cytogenetic data as well as RNA expression and methylation data of gMZBL.

Morphology

gMZBL is predominantly composed of small, centrocyte-like cells [1]. The neoplastic cell populations reside in the marginal zones around reactive B-cell follicles and may expand into the interfollicular region and extend into the follicles which is termed as follicular colonization. In the mucosal lining the neoplastic cells infiltrate the epithelium leading to so called lymphoepithelial lesions, which are defined as clusters of three or more lymphocytes within the epithelium [2]. Thus, gMZBL recapitulates Peyer's patch-type lymphoid tissue[5].

From a clinical point of view an important differential diagnosis for gMZBL is chronic gastritis. Histological scoring to discriminate covert gMZBL lymphoma from chronic gastritis, is based on the Wotherspoon criteria: 0 represent the normal tissue, a score of 1 or 2 chronic gastritis, 5 is assigned for overt gMZBL lymphomas, while a score of 3 or 4 indicates an ambiguous lymphoid infiltration probably reactive or probably neoplastic. In scores 3 and 4 B cell clonality has to be checked, since clonality is an exclusive feature of MALT Lymphoma [6].

Special Stains and Immunohistochemistry

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining can detect H.p., a spiral-shaped bacterium, and the sensitivity and specificity of H&E staining have been reported to be 69-93% and 87-90%, respectively. Special stains, such as modified Giemsa, Warthin-Starry silver stain, Genta stain, and immunohistochemistry (IHC) stain, can improve specificity up to 100% [7].

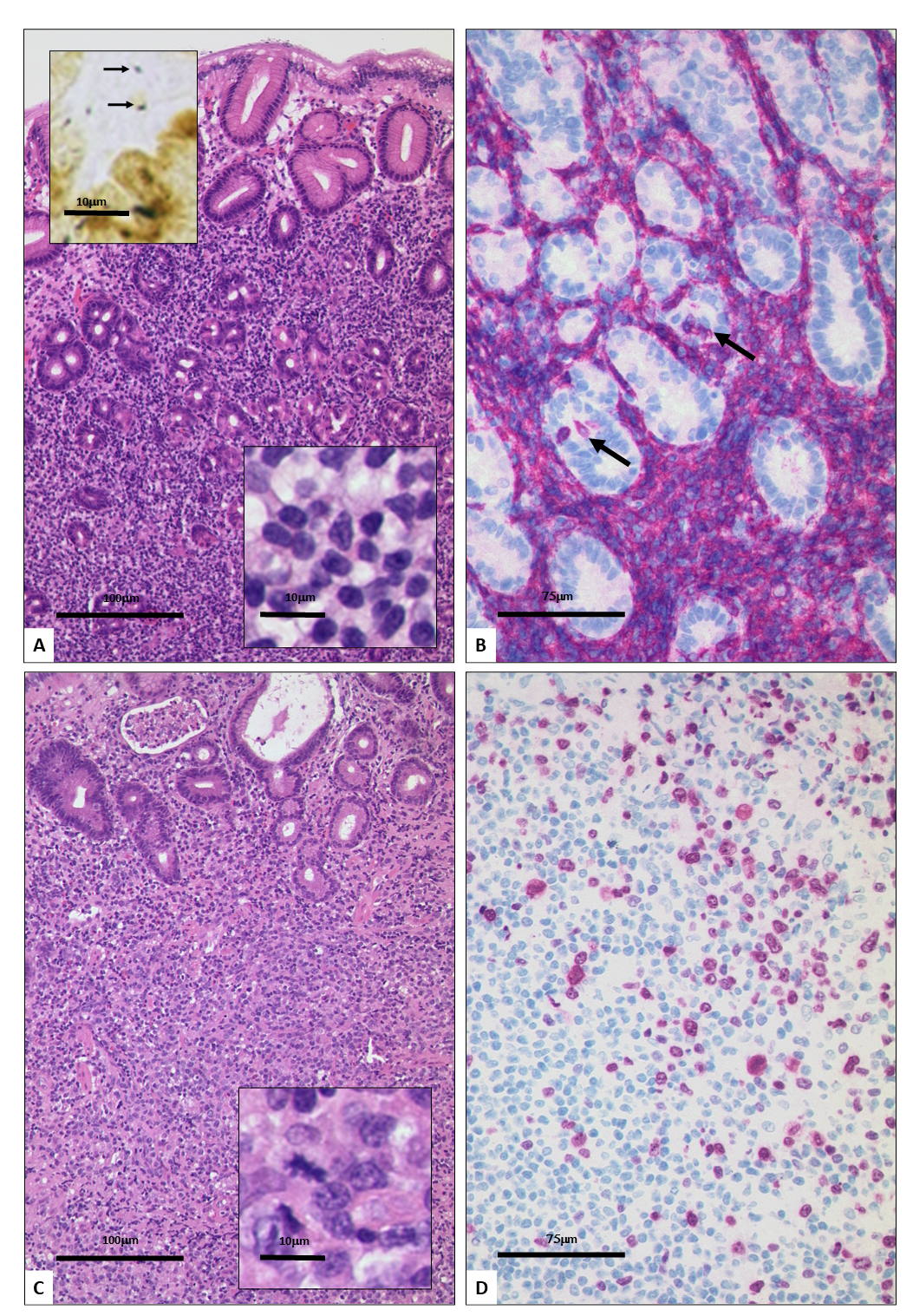

The lymphoma cells of gMZBL are CD20+, CD79a+, CD5-, CD10-, CD23-, CD43+/- and CD11c+/-. Colonized follicles may be highlighted by staining for CD21 and CD23 revealing expanded meshworks of follicular dendritic cells [1,5]. Although IRTA1 has been proposed as a possible specific marker of marginal zone B cell lymphoma still there is no specific marker profile available for gMZBL [8]. However, progression to the large cell variant has been associated with BCL6 de novo expression [9]. Comparing the KI-67 staining of small and large cell gMZBL, the large cell variant is clearly more proliferating. This increase in proliferation is observable also in composite gMZBL as a gradient, showing not a clear separation between the two components, supporting the model for progression from small cell to large cell gMZBL, termed ComL (Figure1).

Figure 1: Histomorphology of a transformed gastric MZBL. The small cell component consists of lymphoid cells with condensed nuclei (insert lower right; high magnification) and disruption of the mucosa (A; Hematoxylin-eosin stain). H. pylori infection is detected in a Whartin-Starry staining (insert; upper left). A CD20 staining shows the lymphoma cells, lymphoepithelial lesions are marked by asterisks (B). The large cell component has a diffuse growth pattern and consists of blastic lymphoid cells (C); insert shows high magnification with a mitotic figure. A KI-67 staining (D) reveals a high number of marked nuclei in the large cell compartment (Upper right) as compared to the small cell compartment with only few marked lymphoma cells (Lower left).

Cytogenetics

The reciprocal translocation of chromosome 11 and chromosome 18 is detected in around 50% of gMZBL but has not been found in the large cell variant [10]. In the t(11;18)(q21;q21) translocation, the apoptosis inhibitor-2 (API2) gene on 11q21 and the MALT-lymphoma–associated translocation (MLT) gene on 18q21 are involved. It has been shown that the fusion of API2 and MLT is implicated in the oncogenesis of extranodal small B-cell lymphomas as a result of the translocation. The absence of the t(11;18)(q21;q21) in the large cell gMZBL can define a landscape of t(11;18)(q21;q21) positive gMZBL being characterized by genomic stability, while t(11;18) negative gMZBL can acquire other aberrations during progression. The t(11;18)-negative group of gMZBL shows an increased number of aberrations including trisomy 3, losses on the long arm of chromosome 13, and gains on chromosome 12 as well as high-level DNA amplifications of proto-oncogenes such as c-REL. The small cell and large cell component of ComL has been separately analyzed using microdissection showing that these aberrations are also detected in the large cell variant. Large-cell components of composite cases and large-cell MALT lymphomas without a small-cell component share some common features such as gains on chromosome 12 and the long arm of chromosome 11 as well as losses on 6q. Therefore, these patterns of overlapping aberrations suggest the action of common secondary events during lymphoma progression of gMZBL [11]. Another specific rearrangement is t(3;14)(q27;q32)/BCL6-IGH that causes the above mentioned de novo expression of BCL6 in large cell gMZBL, making it a new marker for progression. Regarding the pattern of aberrations there is an overlap between small cell and large cell lymphomas suggesting that the increased genomic instability leads to blastic transformation [9]. High-resolution genomic profiling confirmed the increasing complexity along lymphoma progression, with gains in large cell gMZBL of oncogenes such as: REL, BCL11A, EST1, PTPN1, PTEN, and KRAS. For the genes ADAM3A, SCAPER, and SIRPB1 copy numbers were varying between the three different modes of presentation, suggesting that these genes are associated with progression from small to large cell lymphoma. Moreover, there is an overrepresentation of genes associated with NF-κB signaling in the large cell component of ComL and large cell gMZBL, maybe a new hallmark of these. Genes implicated in TP53-mediated cell death (TP53I3, MED1), tumor cell survival (ERBB2, GRB7), and invasion (ASAP3, AIMP1) are only found in acquired uniparental disomy of large cell component of ComL and large cell gMZBL, highlighting the aggressive nature of these lymphoma variants [12].

Evaluation of the mutational landscape has also been done by Vela et al. [13] in a meta-analysis that included 1663 samples of marginal zone lymphoma from various primary sites: for the 59 gMZBL more than 60% of them carried mutations, mostly affecting the NF-κB pathway, chromatin modifiers, and NOTCH, present in 61%, 55%, and 42% of cases, respectively. The most frequently mutated genes were NOTCH1 (17%), NF1 (16%), TNFAIP3 (15%), TRAF3 (13%), and TET2 (13%). Mutations related to the NOTCH pathway tended to be mutually exclusive to mutations of genes of the NF-κB pathway. gMZBL showed a mutational profile similar to that of the primary marginal zone lymphomas of lung, eye, and dura.

RNA Expression Profiling

To elucidate the pathogenetic relationship between components of ComL and primary large cell B-cell lymphoma of the stomach, gene expression analysis has been performed. For this analysis the NF-κB pathway was chosen, well known as being dysregulated in extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphomas. Hierarchical clustering showed that the large cell component of ComL and primary large cell gMZBL group together and are separated from their small-cell counterpart. Moreover, there is an overlap between the differentiating genes of small cell and large cell variant of gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, as well as between the small and large-cell components of ComL isolated by microdissection, underlining a pathogenetic similarity between the small cell component of ComL and primary small cell gMZBL, and between the large cells of ComL and primary large cell gMZBL [14]. The NF-κB signature has been used to perform classification experiments [15]. The model was trained to distinguish large cell gMZBL from the two main variants of DLBCL, ABC, and GCB, and this training resulted in a clear separation of the three groups. These results confirm the individuation of large cell gMZBL as a lymphoma separate from DLBCL.

|

Year |

Key note discovery |

Description |

Authors |

References |

|

1983 |

First description |

Malignant lymphoma of mucosa associated lymphoid tissue. A distinctive subtype of B-cell lymphoma. |

Isaacson et al. |

(1–2) |

|

1991 |

Immunohistochemistry |

Histomorphologic and immunophenotypic spectrum of primary gastro-intestinal B-cell lymphomas. |

Mielke et al. |

(5) |

|

1993 |

Treatment |

Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. |

Wotherspoon et al. |

(3) |

|

1999 |

Cytogenetic |

The Apoptosis Inhibitor Gene API2 and a Novel 18q Gene,MLT, Are Recurrently Rearranged in the t(11;18)(q21;q21) Associated With Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue. |

Dierlamm et al. |

(10) |

|

2001 |

Cytogenetic |

Molecular-cytogenetic comparison of mucosa-associated marginal zone B-cell lymphoma and large B-cell lymphoma arising in the gastro-intestinal tract. |

Barth et al. |

(11) |

|

2007 |

RNA expression profiling |

Transcriptional profiling suggests that secondary and primary large B-cell lymphomas of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are blastic variants of GI marginal zone lymphoma |

Barth et al. |

(14) |

|

2009 |

Methylation |

Accumulation of aberrant CpG hypermethylation by Helicobacter pylori infection promotes development and progression of gastric MALT lymphoma |

Kondo et al. |

(16) |

|

2011 |

Cytogenetic and Immunohistochemistry |

BCL6 gene rearrangement and protein expression are associated with large cell presentation of extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue. |

Flossbach et al. |

(9) |

|

2012 |

Treatment |

Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy is effective in the treatment of early-stage H pylori–positive gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. |

Kuo et al. |

(4) |

|

2013 |

Cytogenetic |

High-resolution genomic profiling reveals clonal evolution and competition in gastrointestinal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma and its large cell variant. |

Flossbach et al. |

(12) |

|

2017 |

RNA expression profiling |

Comparative gene-expression profiling of the large cell variant of gastrointestinal marginal-zone B-cell lymphoma. |

Barth et al. |

(15) |

|

2021 |

Methylation |

Genome-wide DNA methylation analysis along the progression of gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) type. |

Dugge et al. |

(17) |

|

2022 |

Cytogenetic |

Mutational landscape of marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of various origin: organotypic alterations and diagnostic potential for assignment of organ origin |

Vela et al. |

(13) |

Methylation Analysis

It has been observed that hypermethylation in promoter CpG islands induces silencing of tumor suppressor genes, also contributing to gastric lymphoma carcinogenesis. A study conducted by Kondo et al. [16] using methylation-specific PCR showed that the H.p. infection is associated with aberrant hypermethylation of genes such as: Kip2, P16, DAPK, HCAD, MGMT, and MINT31. Interestingly, the same group of genes lost the hypermethylation after the eradication of H.p. in the same patients. The hypothetical mechanism of the influence of H.p. infection on methylation of gastric tissue is the expression of a “H.p. specific” methyltransferase, hpy1M. However, this correlation still needs further confirmation.

The methylation status in gastric MALT lymphomas has been studied on a genome-wide scale by Dugge et al. [17]. The average methylation level was increased during lymphoma progression and there was a clear distinction between small and large-cell MALT lymphomas, as well as between lymphomas and normal B-cells and H.p. infected mucosa. The most relevant difference was hypermethylation, of the promoter region of genes associated with transcriptional regulation found only in large-cell MALT lymphomas. These findings show that morphology is reflected on the epigenetic level.

Conclusion

Clonality analysis paired with immunohistochemical data have shown that there is progression from the small cell variant to the large cell variant of gastric MALT lymphoma. There exists a characteristic marker profile for small cell gMZBL and for its large cell variants, however, a specific immunohistologic marker like Cyclin-D1 for mantle cell lymphoma has yet to be found.

Cytogenetically, there are gains in several genes as the lymphoma progresses (e.g. REL, PTPN1 or KRAS). Specific rearrangements, such as (3;14)(q27;q32)/BCL6-IGH going along with expression of BCL6 were exclusively found in large cell variant of gMZBL. Furthermore, genes related to the NFKB pathway were overrepresented in large cell variant of gMZBL and appear as a hallmark of it.

These findings taken together and completed with the expression data provide clear evidence that the large cell variant of gMZBL is a lymphoma distinct from conventional DLBCL. For this lymphoma we coined the term blastic marginal zone lymphoma of MALT, in analogy to blastic variant of mantle cell lymphoma.

References

2. Wotherspoon AC, Ortiz-Hidalgo C, Falzon MR, Isaacson PG. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis and primary B-cell gastric lymphoma. The Lancet. 1991 Nov 9;338(8776):1175-6.

3. Wotherspoon AC, Diss TC, Pan L, Isaacson PG, Doglioni C, Moschini A, De Boni M. Regression of primary low-grade B-cell gastric lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. The Lancet. 1993 Sep 4;342(8871):575-7.

4. Kuo SH, Yeh KH, Wu MS, Lin CW, Hsu PN, Wang HP, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy is effective in the treatment of early-stage H pylori–positive gastric diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2012 May 24;119(21):4838-44.

5. Mielke B, Möller P. Histomorphologic and immunophenotypic spectrum of primary gastro‐intestinal B‐Cell lymphomas. International journal of cancer. 1991 Feb 1;47(3):334-43.

6. Hummel M, Oeschger S, Barth TF, Loddenkemper C, Cogliatti SB, Marx A, et al. Wotherspoon criteria combined with B cell clonality analysis by advanced polymerase chain reaction technology discriminates covert gastric marginal zone lymphoma from chronic gastritis. Gut. 2006 Jun 1;55(6):782-7.ss

7. Lee JY, Kim N. Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori by invasive test: histology. Annals of translational medicine. 2015 Jan;3(1).

8. Falini B, Agostinelli C, Bigerna B, Pucciarini A, Pacini R, Tabarrini A, Falcinelli F, et al. IRTA1 is selectively expressed in nodal and extranodal marginal zone lymphomas. Histopathology. 2012 Nov;61(5):930-41.

9. Flossbach L, Antoneag E, Buck M, Siebert R, Mattfeldt T, Möller P, et al. BCL6 gene marginal zone B‐cell lymphoma of mucosa‐associated lymphoid tissue. International Journal of Cancer. 2011 Jul 1;129(1):70-7.

10. Dierlamm J, Baens M, Wlodarska I, Stefanova-Ouzounova M, Hernandez JM, Hossfeld DK, et al. The apoptosis inhibitor gene API2 and a novel 18q gene, MLT, are recurrently rearranged in the t(11;18)(q21;q21) associated with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphomas. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 1999 Jun 1;93(11):3601-9.

11. Barth TF, Bentz M, Leithäuser F, Stilgenbauer S, Siebert R, Schlotter M, et al. Molecular‐cytogenetic comparison of mucosa‐associated marginal zone B‐cell lymphoma and large B‐cell lymphoma arising in the gastro‐intestinal tract. Genes, Chromosomes and Cancer. 2001 Aug;31(4):316-25.

12. Flossbach L, Holzmann K, Mattfeldt T, Buck M, Lanz K, Held M, et al. High‐resolution genomic profiling reveals clonal evolution and competition in gastrointestinal marginal zone B‐cell lymphoma and its large cell variant. International Journal of Cancer. 2013 Feb 1;132(3):E116-27.

13. Vela V, Juskevicius D, Dirnhofer S, Menter T, Tzankov A. Mutational landscape of marginal zone B-cell lymphomas of various origin: organotypic alterations and diagnostic potential for assignment of organ origin. Virchows Archiv. 2022 Feb;480(2):403-13.

14. Barth TF, Barth CA, Kestler HA, Michl P, Weniger MA, Buchholz M, et al. Transcriptional profiling suggests that secondary and primary large B‐cell lymphomas of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract are blastic variants of GI marginal zone lymphoma. The Journal of Pathology: A Journal of the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 2007 Feb;211(3):305-13.

15. Barth TF, Kraus JM, Lausser L, Flossbach L, Schulte L, Holzmann K, et al. Comparative gene-expression profiling of the large cell variant of gastrointestinal marginal-zone B-cell lymphoma. Scientific Reports. 2017 Jul 20;7(1):1-8.

16. Kondo T, Oka T, Sato H, Shinnou Y, Washio K, Takano M, et al. Accumulation of aberrant CpG hypermethylation by Helicobacter pylori infection promotes development and progression of gastric MALT lymphoma. International Journal of Oncology. 2009 Sep 1;35(3):547-57.

17. Campo E, Swerdlow SH, Harris NL, Pileri S, Stein H, Jaffe ES. The 2008 WHO classification of lymphoid neoplasms and beyond: evolving concepts and practical applications. Blood, The Journal of the American Society of Hematology. 2011 May 12;117(19):5019-32.