Abstract

Fecal Microbiota Transfer (FMT) is a procedure that has proven to be highly effective and safe for the treatment of recurrent or refractory Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI). FMT also emerges as a promising approach in other indications such as ulcerative colitis (UC) or acute graft-versus-host disease (aGvHD). However, translatability and reproducibility of studies using single-donor FMT remain limited due to the intrinsic variability in taxonomic composition of donors-derived products. Accumulating evidence suggests that by increasing microbial richness and standardizing taxonomic composition, pooled FMT can increase microbial engraftment, and improve treatment efficacy in receiving patients. Recent research has highlighted the advantages of pooled donor strategies over single-donor approaches in UC. The recent success of MaaT013, a standardized allogeneic fecal microbiotherapy derived from pooled healthy human fecal microbiota, in aGvHD underscores its potential across different indications associated with gut dysbiosis. Future research directions include developing standardized protocols for donor screening, product manufacturing, administration procedures, as well as harmonized regulatory framework.

Keywords

Fecal microbiota transfer (FMT), Pooling, Microbial diversity, Engraftment, Ulcerative colitis, Safety, Efficacy, Standardization, Acute graft-versus-host disease

Introduction

Fecal microbiota transfer (FMT) has proven to be highly effective and safe for the treatment of recurrent or refractory Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) in patients by restoring the gut microbiota and preventing further recurrences [1]. FMT has also emerged as a promising approach in other indications such as acute graft-versus-host disease (aGvHD) [2] or ulcerative colitis (UC) [3,4]. However, the intrinsic variability in taxonomic composition of donors-derived products limits the translatability of these studies. Recent research has highlighted the advantages of pooled donor strategies over single-donor approaches [5]. This commentary evaluates the safety and efficacy of pooled FMT, synthesizing evidence from meta-analyses, preclinical studies, and clinical trials to underscore its potential for UC management and for broader applications.

Methods

Pooled microbiotherapy (MaaT013) manufacturing

MaaT013 is a standardized and high-richness microbiotherapy product manufactured in a European cGMP production facility by pooling fecal material from 3 to 8 strictly vetted, healthy donors, using a proprietary cryoprotectant (patent number FR1553716) preserving a high concentration of viable cells in the drug substance (minimum of 1.35 x 1011 viable bacteria par bag of 150 mL). The overall manufacturing process for MaaT033 closely mirrors that of MaaT013 [2], with the key addition of lyophilization and encapsulation steps [6], which preserve the comparable properties and composition shared by both products.

DNA isolation and 16S rDNA sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from fecal samples using the NucleoSpin Soil kit (Macherey Nagel). A sequencing library targeting the V3-V4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was constructed for each sample using the MyTaq HS-Mix (Bioline) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were then sequenced in paired-end (2 x 300 bp) MiSeq runs (Illumina). Positive and negative controls were added throughout the process to validate the successful completion of each step.

Bioinformatics analyses

16S rDNA bioinformatics analyses were performed on the gutPrint® platform with the in-house MgTagRunner v2.0.0 pipeline. In brief, after amplicon merging using FLASH [7], reads were quality-filtered using Trimmomatic [8]. Amplicons were clustered into operational taxonomic units (OTUs) with an identity threshold of 97%. A taxonomic annotation was then assigned to each output using VSEARCH3 [9] and the Silva SSU database (Release 128). To allow data comparison, the number of sequences was normalized to 60,000 amplicons per sample. The richness and Bray-Curtis indices were calculated using R Statistical Software (R Core Team 2018, version 3.4.4) using vegan and phyloseq packages.

Results

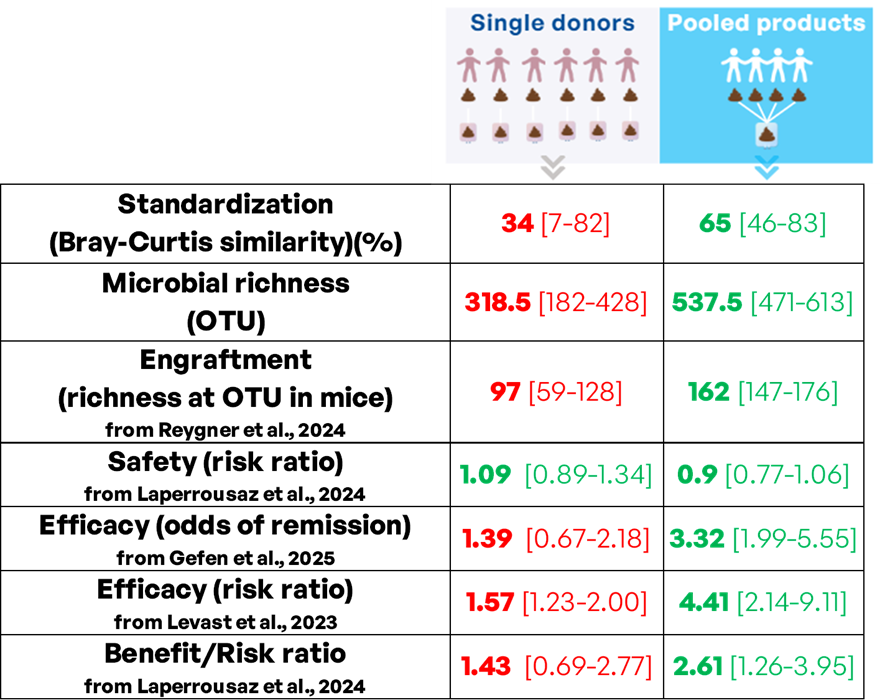

Levast et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis comparing pooled and single-donor FMT strategies in patients with UC [10]. The analysis included 14 controlled studies and found that both pooled and single-donor FMT products were superior to placebo in inducing clinical response (risk ratios [RRs]: 4.41 and 1.57, respectively [p≤0.001 for both]). Importantly, pooled FMT showed a significantly higher treatment response rate than single-donor FMT ([RRs]: 2.81, p=0.005). Laperrousaz et al. performed a systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on safety and efficacy of pooled and single-donor FMT in UC patients [11]. The analysis included 15 controlled studies (587 patients) and found that pooled and single-donor FMTs had similar safety profiles, with no significant difference in adverse or serious adverse events rate. Importantly, when considering both efficacy and safety, pooled FMT had a greater benefit-risk ratio compared to single-donor FMT, reinforcing its clinical advantage. The authors recommend further development of pooled FMT for UC, given its superior efficacy and comparable safety to single-donor FMT. Gefen et al. conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials evaluating FMT for UC [5]. The study included 14 trials (600 patients) and demonstrated similar safety profiles between FMT and control groups. FMT significantly improved combined clinical and endoscopic remission rates compared to placebo (odds ratio 2.25, p<0.0001), with pooled FMT (odds ratio 3.32) and oral FMT administration (odds ratio 3.15) showing superior efficacy. The use of adjunct treatments (biologics, steroids, or methotrexate) concomitant or before the delivery of FMT further enhanced remission rates, supporting FMT as a promising therapeutic modality for UC.

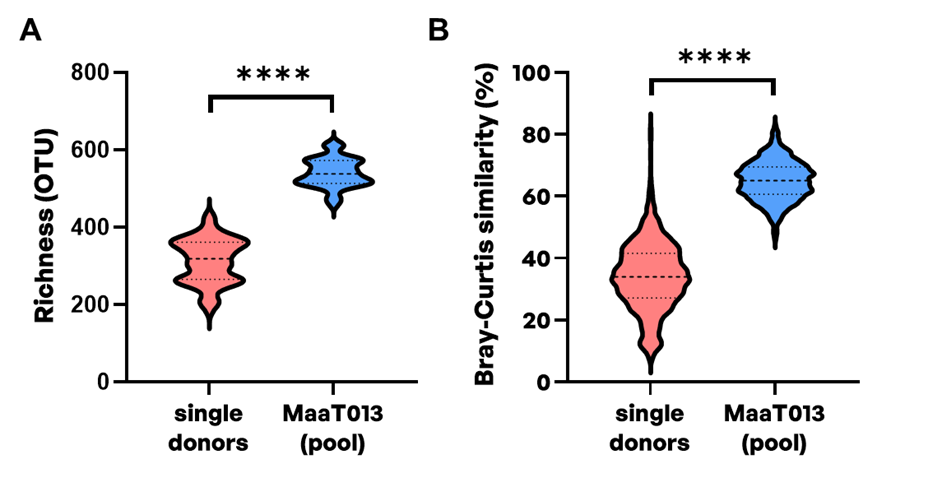

A critical property that distinguishes single-donor FMTs and pooled products is their microbial diversity, and notably their microbial richness corresponding to the number of different taxa in a microbial community. Comparing the microbial richness at operational taxonomic units (OTU) level between single-donors and corresponding pooled MaaT013 products, an improved microbial richness can be achieved (median of 318.5 OTU [182-428] for single donors compared to 537.5 OTU [471-613] for pooled MaaT013 products) (Figure 1A). Higher richness of donor feces has been associated with improved clinical success of FMT in patients with UC [12,13]. Higher donor feces microbial diversity was further identified as predictive of a response in a systematic review of 25 studies evaluating FMT in patients with UC [14]. In addition, pooling feces from several donors also allows to decrease batch-to-batch variability through standardization of microbial taxonomic composition. This was evidenced by an inter-batch Bray-Curtis similarity index at OTU level of 65% [46-83%] for pooled MaaT013 products (Figure 1B). Conversely, corresponding single-donor derived products suffer from highly heterogeneous microbial composition with an inter-batch Bray-Curtis similarity index at OTU level of 34% [7-82%], limiting reproducibility and consistency of therapeutic outcomes.

Figure 1. Microbial richness and Bray-Curtis similarity index in single-donor and corresponding MaaT013 (pooled) microbiotherapy products. 16S rDNA sequencing was performed to evaluate A) microbial richness at operational taxonomic unit (OTU) level and B) intra-groups Bray-Curtis similarities at OTU level for single-donors (n=78 fecal samples from 22 donors) and corresponding pooled MaaT013 batches (n=38). MaaT013 was manufactured through the pooling of feces from 4 to 8 strictly vetted healthy donors. The Bray-Curtis similarity index was calculated using one fecal sample per donor. Violin plots with median and range are presented. Statistical significances were evaluated using Wilcoxon test (**** p≤0.0001).

Microbial engraftment is defined as the number of donor-derived microbial species that successfully colonize the recipient’s gut. In addition, the administration of one FMT product to several recipients leads to differential strain engraftment, supporting the concept of donor-recipient compatibility [15]. By offering a wider range of microbial species to recipient patients, highly rich pooled FMT products are expected to be associated with higher microbial engraftment by increasing the probability of donor-recipient matching [16]. This was recently evidenced in vivo by Reygner et al., where mice treated with pooled microbiotherapy products reached higher microbial richness compared to mice treated with corresponding single donor-derived products [17]. In this study, the heterogeneity in efficacy of single donor-derived products to treat infectious diseases was corrected by pooled fecal microbiotherapy. Higher donor strain engraftment was associated with improved clinical success after FMT across different studies [18,19]. Accordingly, a trend towards a linear relationship between bacterial diversity in fecal donations and post-FMT clinical outcomes has recently been observed in CDI [20]. Finally, a meta-analysis recently evidenced that the switch from low to high gut microbial diversity was associated with an improved clinical response of UC patients to FMT treatment [21]. Altogether, these results suggest that by improving microbial diversity and increasing the probability of donor-recipient matching, the use of pooled fecal microbiotherapies could improve microbial engraftment and treatment efficacy in receiving patients (Figure 2). Thus, pooled fecal microbiotherapies tailored to match the specific microbial needs of many individuals could improve patient care [22].

Figure 2. Comparison between single-donor and pooled products (FMT procedure or microbiotherapy). This figure synthesize evidence from metagenomic analysis, preclinical studies and meta-analyses of clinical trials in UC. Median and range are indicated.

Discussion

In line with predictive models [23], these findings support the use of pooled fecal microbiotherapies to improve engraftment and treatment outcomes without compromising safety, with potential implications for UC and other indications that could benefit from fecal microbiotherapies. Indeed, promising clinical results were obtained using pooled fecal microbiotherapies to treat UC [24,25], but also for the treatment of other indications such as irritable bowel syndrome [26], or aGvHD [2].

Conventional FMT is often prepared in hospitals using feces from healthy donor(s), on a non-routine basis, for individual patients under medical prescription and administered to these patients locally. Fecal microbiotherapy refers to pharmaceutical-grade standardized medicinal products prepared routinely following reproducible industrial manufacturing process (which includes pooling of donations) and according to consistent quality standards. These products are intended to be administered to recipients on a large scale with the objective of restoring a balanced gastro-intestinal (GI) microbiota and thereby improving the health status of the patients.

MaaT013, a standardized allogeneic fecal microbiotherapy derived from pooled healthy human fecal microbiota and administered via rectal enema, has demonstrated promising results to treat steroid-resistant GI aGvHD patients in the phase 2 HERACLES study [2]. MaaT013 was safe in this highly immunocompromised patient population. Interestingly, clinical response was linked to the increased microbiota richness resulting from the engraftment of fecal material from several donors. Increased levels of beneficial bacteria, in particular butyrate producers, along with increased levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) and secondary bile acids were found in the feces of responding patients. MaaT013 is currently being investigated in refractory aGvHD with GI involvement in the pivotal ARES trial [27]. The study met its primary endpoint with a significant GI overall response rate (GI-ORR) at Day 28 of 62% and a 1-year expected overall survival of 54%, demonstrating the unprecedented efficacy of MaaT013 as third-line treatment of aGvHD with GI involvement [28]. Finally, pooled oral fecal microbiotherapies are also currently being developed. MaaT033, a pooled, allogeneic, lyophilized, and standardized fecal microbiotherapy product, formulated as a delayed-release capsule for oral administration was shown to be safe and effective for gut microbiota restoration in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients receiving intensive chemotherapy and antibiotics in the phase 1 CIMON clinical trial [6]. MaaT033 restored microbial communities close to the composition of the drug product and was associated with a decrease in inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein, interleukin-6) together with an increase in SCFA over time. MaaT033 is currently being tested in the randomized, placebo-controlled phase 2b PHOEBUS trial, evaluating its efficacy to improve survival in patients receiving allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation [29]. These studies highlight the shift toward pooled fecal microbiotherapies for conditions caused by gut dysbiosis.

Some aspects may be addressed to improve clinical efficacy of fecal microbiotherapies and achieve reproducible results. Future directions include developing standardized protocols for donor screening, product manufacturing process, and administration procedures. Donor selection is an important factor influencing safety of fecal microbiotherapies. The safety of microbiotherapy products is intrinsically linked to the rigorous screening and testing of both fecal microbiota donors and fecal material to minimize the risk of pathogen transmission. As such, a harmonized regulatory framework is needed to ensure strict donor screening procedures. To this end, the European substances of human origin (SoHO) regulation has been set to establish measures setting high standards of quality and safety for all intended human applications and activities related to intestinal microbiota [30]. In addition, current consensus is that FMT efficacy is associated with successful engraftment of donor species. Thus, strategies that would allow to improve microbiota engraftment such as ensuring bacteria viability, increase in dose and frequency of FMT administration as well as the use of high-richness pooled-donor products are advised [15,19]. While no proper FMT dose-response study was performed, the dosing regimen of fecal microbiotherapies in term of number of living bacteria and number of administrations needs to be extensively analyzed. The need and the nature of pre-treatment (antibiotics or PEG) to free ecological space in the gastrointestinal tract and facilitate the engraftment of donor microbes should also be addressed. Finally, safety, efficacy and cost of FMT do not only depend on the quality of contents but also on the delivery route employed. Delivery routes for FMT include upper gastrointestinal routes through nasogastric/nasojejunal tubes, endoscopy, oral capsules and lower gastrointestinal routes like retention enema, sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy. While progresses were recently achieved [31], the optimal route for FMT administration is yet to be established and may depend on the degree of intestinal dysbiosis associated with specific indications. Extensive studies are required to understand the interplay between administration route, physical nature of FMT (fresh or frozen), patient compliance and cost effectiveness to design a risk-free, convenient and cost-effective FMT [32,33].

Conclusion

In conclusion, the pooling strategy represents a paradigm shift for fecal microbiotherapies, offering comparable safety to single-donor products while achieving superior efficacy through enhanced microbial diversity and engraftment. The ability of pooled fecal microbiotherapies to deliver diverse and standardized microbial communities positions it as a superior option for UC. The success of pooled fecal microbiotherapy in aGvHD underscore its potential across different indications associated with gut dysbiosis.

Conflict of Interest

J.D. is Scientifc Advisor to MaaT Pharma. All other authors are employed by MaaT Pharma.

Author Contributions

B.L. and M.F. performed the literature review. C.G. and A.D performed metagenomic analysis. B.L. wrote the manuscript. J.D. contributed to discussions. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the article.

Acknowledgements

We thank Pauline Richaud, Alice Rouanet, PharmD, and Gianfranco Pittari, MD, PhD, for reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by MaaT Pharma, France; http://www.maatpharma.com.

References

2. Malard F, Loschi M, Huynh A, Cluzeau T, Guenounou S, Legrand F, et al. Pooled allogeneic faecal microbiota MaaT013 for steroid-resistant gastrointestinal acute graft-versus-host disease: a single-arm, multicentre phase 2 trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2023 Jul 26;62:102111.

3. Lopetuso LR, Deleu S, Puca P, Abreu MT, Armuzzi A, Barbara G, et al. Guidance for Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Trials in Ulcerative Colitis: The Second ROME Consensus Conference. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2025 Feb 11:izaf013.

4. Zhang JT, Zhang N, Dong XT, Wang XR, Ma HW, Liu YD, et al. Efficacy and safety of fecal microbiota transplantation for treatment of ulcerative colitis: A post-consensus systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Clin Cases. 2024 Jul 26;12(21):4691–702.

5. Gefen R, Dourado J, Emile SH, Wignakumar A, Rogers P, Aeschbacher P, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for patients with ulcerative colitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized control trials. Tech Coloproctol. 2025 Apr 17;29(1):103.

6. Malard F, Thepot S, Cluzeau T, Carre M, Lebon D, Bories P, et al. Gut microbiota restoration with oral pooled fecal microbiotherapy after intensive chemotherapy: the phase Ib CIMON trial. Blood Adv. 2025 Apr 8:bloodadvances.2024015571.

7. Magoč T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics. 2011 Nov 1;27(21):2957–63.

8. Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014 Aug 1;30(15):2114–20.

9. Rognes T, Flouri T, Nichols B, Quince C, Mahé F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ. 2016 Oct 18;4:e2584.

10. Levast B, Fontaine M, Nancey S, Dechelotte P, Doré J, Lehert P. Single-Donor and Pooling Strategies for Fecal Microbiota Transfer Product Preparation in Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2023 May 1;14(5):e00568.

11. Laperrousaz B, Levast B, Fontaine M, Nancey S, Dechelotte P, Doré J, et al. Safety comparison of single-donor and pooled fecal microbiota transfer product preparation in ulcerative colitis: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024 Nov 11;24(1):402.

12. Kump P, Wurm P, Gröchenig HP, Wenzl H, Petritsch W, Halwachs B, et al. The taxonomic composition of the donor intestinal microbiota is a major factor influencing the efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation in therapy refractory ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018 Jan;47(1):67–77.

13. Vermeire S, Joossens M, Verbeke K, Wang J, Machiels K, Sabino J, et al. Donor Species Richness Determines Faecal Microbiota Transplantation Success in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2016 Apr;10(4):387–94.

14. Rees NP, Shaheen W, Quince C, Tselepis C, Horniblow RD, Sharma N, et al. Systematic review of donor and recipient predictive biomarkers of response to faecal microbiota transplantation in patients with ulcerative colitis. EBioMedicine. 2022 Jul;81:104088.

15. Podlesny D, Durdevic M, Paramsothy S, Kaakoush NO, Högenauer C, Gorkiewicz G, et al. Identification of clinical and ecological determinants of strain engraftment after fecal microbiota transplantation using metagenomics. Cell Rep Med. 2022 Aug 16;3(8):100711.

16. Wilson BC, Vatanen T, Jayasinghe TN, Leong KSW, Derraik JGB, Albert BB, et al. Strain engraftment competition and functional augmentation in a multi-donor fecal microbiota transplantation trial for obesity. Microbiome. 2021 May 13;9(1):107.

17. Reygner J, Delannoy J, Barba-Goudiaby M-T, Gasc C, Levast B, Gaschet E, et al. Reduction of product composition variability using pooled microbiome ecosystem therapy and consequence in two infectious murine models. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2024 May 21;90(5):e0001624.

18. Ianiro G, Punčochář M, Karcher N, Porcari S, Armanini F, Asnicar F, et al. Variability of strain engraftment and predictability of microbiome composition after fecal microbiota transplantation across different diseases. Nat Med. 2022 Sep;28(9):1913–23.

19. Porcari S, Benech N, Valles-Colomer M, Segata N, Gasbarrini A, Cammarota G, et al. Key determinants of success in fecal microbiota transplantation: From microbiome to clinic. Cell Host Microbe. 2023 May 10;31(5):712–33.

20. Karmisholt Grosen A, Mikkelsen S, Aas Hindhede L, Ellegaard Paaske S, Dahl Baunwall SM, Mejlby Hansen M, et al. Effects of clinical donor characteristics on the success of faecal microbiota transplantation for patients in Denmark with Clostridioides difficile infection: a single-centre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Microbe. 2025 May;6(5):101034.

21. Bénard MV, de Goffau MC, Blonk J, Hugenholtz F, van Buuren J, Paramsothy S, et al. Gut Microbiota Features in Relation to Fecal Microbiota Transplantation Outcome in Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2024 Oct 21:S1542–3565(24)00907–8.

22. Ishikawa D, Watanabe H, Nomura K, Zhang X, Maruyama T, Odakura R, et al. Patient-donor similarity and donor-derived species contribute to the outcome of fecal microbiota transplantation for ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2025 Apr 4;19(4):jjaf054.

23. Kazerouni A, Wein LM. Exploring the Efficacy of Pooled Stools in Fecal Microbiota Transplantation for Microbiota-Associated Chronic Diseases. PLoS One. 2017 Jan 9;12(1):e0163956.

24. Kedia S, Virmani S, K Vuyyuru S, Kumar P, Kante B, Sahu P, et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation with anti-inflammatory diet (FMT-AID) followed by anti-inflammatory diet alone is effective in inducing and maintaining remission over 1 year in mild to moderate ulcerative colitis: a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2022 Dec;71(12):2401–13.

25. Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, Walsh AJ, van den Bogaerde J, Samuel D, et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2017 Mar 25;389(10075):1218–28.

26. Mohan BP, Loganathan P, Khan SR, Garg G, Muthusamy A, Ponnada S, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant delivered via invasive routes in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2023 Jun;42(3):315–23.

27. MaaT Pharma, 2024. Evaluation of the Efficacy of MaaT013 As Salvage Therapy in Acute GVHD Patients with Gastrointestinal Involvement, Refractory to Ruxolitinib; a Multi-center Open-label Phase III Trial. (Clinical trial registration No. NCT04769895). clinicaltrials.gov.

28. MaaT Pharma, 2025. May 13, 2025: MaaT Pharma Provides Business Update and Reports Financial Results for the First Quarter 2025. MaaT Pharma. URL https://www.maatpharma.com/may-13-2025-maat-pharma-provides-business-update-and-reports-financial-results-for-the-first-quarter-2025/ (accessed 6.5.25).

29. Malard F, Labopin M, Holler E, Doré J, Plantamura E, Mohty M. A Multicentre, Randomized, Double-Blinded, Phase 2b Study Evaluating the Efficacy and Safety of MaaT033, an Oral, Pooled Microbiome Ecosystem Therapy in Patients Undergoing Allogenic Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation to Improve Overall Survival: The Phoebus Trial. Blood. 2023 Nov 2;142:4947.

30. Regulation (EU) 2024/1938 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 June 2024 on standards of quality and safety for substances of human origin intended for human application and repealing Directives 2002/98/EC and 2004/23/EC (Text with EEA relevance), 2024.

31. Quraishi MN, Moakes CA, Yalchin M, Segal J, Ives NJ, Magill L, et al. Determining the optimal route of faecal microbiota transplant in patients with ulcerative colitis: the STOP-Colitis pilot RCT. Southampton (UK): National Institute for Health and Care Research; 2024 Aug.

32. Gulati M, Singh SK, Corrie L, Kaur IP, Chandwani L. Delivery routes for faecal microbiota transplants: Available, anticipated and aspired. Pharmacol Res. 2020 Sep;159:104954.

33. Malik S, Naqvi SAA, Shadali AH, Khan H, Christof M, Niu C, et al. Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) and Clinical Outcomes Among Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Patients: An Umbrella Review. Dig Dis Sci. 2025 May;70(5):1873–96.