Abstract

Wnt signaling has long been implicated in cancer development, but recent studies have revealed new insights into how Wnt ligands themselves drive metastasis. Currently, research identifies Wnt1, Wnt2, Wnt2b, Wnt3, Wnt3a, Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt5b, Wnt6, Wnt8a, Wnt9b, Wnt10a, Wnt10b, and Wnt16 as pro-metastatic Wnt ligands, while Wnt7a, Wnt7b, Wnt8b, Wnt9a, and Wnt11 exhibit conflicting pro- and anti-metastatic roles. These ligands arise from diverse sources in the tumor microenvironment and perform a wide range of roles in the metastatic cascade, including epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, matrix metalloproteinase production, cell motility, angiogenesis, cell death resistance, and mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition. Their diverse and critical roles in metastasis make Wnt ligands attractive therapeutic targets.

Keywords

Wnt, Metastasis, Wnt/β-catenin signaling, EMT, Angiogenesis, Cancer therapeutics

Abbreviations

CAF: Cancer-Associated Fibroblast; EMT: Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition; FZD: Frizzled Receptor; LRP5/6: Low-Density Lipoprotein Receptor-Related Protein 5 or 6; MET: Mesenchymal-to-Epithelial Transition; MMP: Matrix Metalloproteinase; TAM: Tumor-Associated Macrophage; TME: Tumor Microenvironment

Introduction

The Wnt pathway is an evolutionarily conserved cell signaling system that has long been implicated in the pathogenesis of cancer. Of note, Wnt pathway mutations drive 90% of human colorectal cancers, underscoring the critical role of Wnt signaling in the regulation of cancer biology cell processes. A key component of cancer progression is the ability to invade and metastasize, facilitating the development of secondary tumors in remote locations of the body [1,2]. Once cancer metastasizes, survival rates plummet [2,3]. While the general outline of the metastatic cascade has been defined, many molecular signals and mechanisms promoting cancer cell dissemination, homing, and implantation in distant organs remain poorly understood. Recent studies implicate Wnt ligands and Wnt signaling as important contributors to metastasis and poor outcomes [4,5].

Wnt ligands are small morphogens that stimulate the Wnt pathway, playing crucial roles in development, cell proliferation, differentiation, and carcinogenesis [6-9]. They are hydrophobic and modified by palmitoleic acid, traveling short distances to mediate their effects [10,11]. The first member of the Wnt signaling pathway was discovered in the early 1970s with the identification of the wingless (wg) gene, which plays a key role in Drosophila wing development [12,13]. Fifteen years later, a proto-oncogenic homolog of wingless, Int1, was discovered [14,15], and the name Wnt (a combination of wg and Int1) was established. β-Catenin, the primary downstream effector of the canonical Wnt pathway, was first identified for its role in adherens junction formation [16,17]. Only later was it shown that β-catenin, together with the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor suppressor protein (frequently mutated in colorectal cancer), regulates Wnt signaling [18–24]. Since the identification of int-1 (Wnt1), 18 other Wnt ligands have been characterized with different capacities to activate the Wnt/β-catenin pathway and with differential tissue expression patterns [25]. Wnt ligands are known to be secreted by tumor cells themselves as well as by various types of tumor-adjacent cells, including cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs), tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), and other stromal cells in the tumor microenvironment (TME). These secreted Wnt ligands have the potential to promote metastasis via their activation of Wnt signaling in the tumor cells and in the microenvironment of metastatic sites [26–29].

The current review will provide an overview of the 19 human Wnt ligands and their distinct contributions in the metastatic process. A thorough understanding of the Wnt-driven metastatic mechanisms will facilitate future drug targeting of this deadly cancer process.

Wnt Signaling

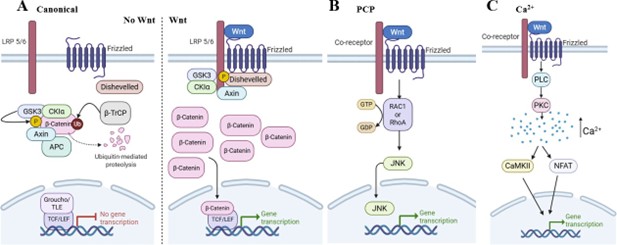

There are two major subdivisions of Wnt signaling: canonical and non-canonical (Figure 1). Canonical Wnt or Wnt/b-catenin signaling regulates transcription through the pathway’s key effector, β-catenin. In the absence of Wnt ligands, a large-molecular-weight β-catenin destruction complex, comprising adenomatous polyposis coli (APC), Axin, casein kinase 1 alpha (CK1α), and glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), phosphorylates β-catenin [30,31]. This phosphorylation, mediated by CK1α and GSK3, allows β-catenin to be recognized by the E3 ligase, β?TrCP, leading to its ubiquitylation and proteasomal degradation. As a result, cytoplasmic and nuclear β-catenin levels remain low, and Wnt transcription is suppressed by Groucho/TLE [31]. The canonical Wnt pathway is stimulated by the presence of Wnt ligands, which bind to Frizzled (FZD) and low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5 or 6 (LRP5/6) receptors. This promotes the receptors’ oligomerization, in a process dependent on the cytoplasmic protein, Disheveled (Dvl). Inhibition of the β-catenin destruction complex occurs when Axin, CK1α, and GSK3 are brought to the membrane via interaction with the activated Wnt receptor complex [7]. Consequently, degradation of cytoplasmic β-catenin is inhibited, allowing β-catenin to accumulate, translocate into the nucleus, displace Groucho/TLE, bind TCF/LEF, and activate Wnt-specific gene transcription [7,30,31].

Figure 1. The classical Wnt signaling pathways. (A) The canonical Wnt signaling pathway, when there is (left) no Wnt ligand present and (right) when there is Wnt ligand present. (B) The Wnt/Planar cell polarity (PCP) signaling pathway. (C) The Wnt/Ca2+ signaling pathway.

Non-canonical Wnt signaling is traditionally divided into, at minimum, two pathways: Wnt/PCP and Wnt/Ca2+. Stimulation of the Wnt/PCP pathway leads to activation of small GTPases, such as RAC1 and RhoA, leading to JUN N-terminal kinase (JNK) activation, which regulates cell polarity, motility, and target gene transcription [32]. Stimulation of the Wnt/Ca2+ pathway activates phospholipase C (PLC) and protein kinase C (PKC), increasing intracellular Ca2+ levels. This Ca2+ activates calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (CaMKII) and the nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) pathway to mediate target gene transcription [7,32].

There is accumulating evidence that specific Wnt, Frizzled, and co-receptor complexes determine which Wnt signaling pathway is activated [33-36]. For example, Frizzled receptors in complex with LRP5/6 co-receptors are classically considered activators of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, as LRP5/6 plays a critical role in inhibiting the β-catenin destruction complex [37]. LRP5/6 encodes two Wnt binding sites (β-propeller regions E1-E2 and E3-E4), each of which can independently bind Wnt ligands, and Wnt ligands and antagonists have been grouped into classes with preference for the two sites, which may dictate the extent of pathway activity [38,39]. In addition, individual Frizzled receptors can participate in multiple signaling pathways, depending on the co-receptor with which they are paired [40-42]. For example, pairing with the co-receptor, PTK7, can activate the calcium pathway, which involves downstream effectors PKC and NFAT [40]. Another co-receptor, RYK, acts to regulate the planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway to regulate neurite outgrowth [43]. The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) has also been shown to be a cofactor for Wnt9a-Fzd9b signaling [44]. Finally, certain Wnt ligands (e.g., Wnt5a) can bind the single-pass Ror1/2 receptor to active PCP signaling [45]. Despite their stark differences, both canonical and non-canonical signaling pathways induce the expression of numerous genes that are highly associated with cancer development and progression.

Metastasis

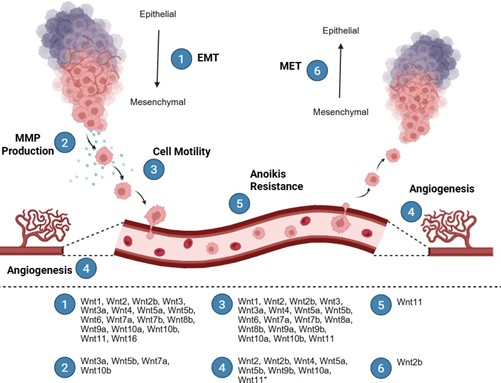

A major hallmark of cancer is the development of invasion and metastasis, enabling the spread of tumor cells to distant sites [1,2]. This process occurs through multiple steps known as the metastatic cascade. Metastasis begins when a tumor cell undergoes the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) [3]. EMT allows for the tumor cell to take on a mesenchymal phenotype, supporting invasion, resisting stress, and dissemination [3]. This process is typically characterized by a downregulation of epithelial proteins, including E-cadherin and cytokeratin, and an upregulation of mesenchymal proteins, including N-cadherin, vimentin, and twist [46]. While not typically considered EMT markers, many cells will also increase their expression of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) to aid their trafficking through the extracellular matrix [47,48]. Consequently, these cancer cells acquire stem-like characteristics, develop phenotypic plasticity, and exhibit enhanced motility [3,46]. Once a tumor cell has undergone EMT, it can extravasate through the endothelium into the bloodstream or lymphatic vessel [3,49]. While in the vessels, the cells must then be able to overcome the next big hurdle of metastasis: anoikis, or programmed cell death. This step is a critical barrier to metastasis, as most cells succumb to cell death once they reach the bloodstream due to the lack of adherence and structural support [50]. If the tumor cells are able to survive the circulation, they then must undergo extravasation to leave the vessel [3,49]. It is not clear whether cells extravasate due to physical cues, such as entrapment in small capillaries, or due to finding a suitable premetastatic niche [3,51]. Regardless, once these cancer cells have extravasated out of a vessel, they must then colonize a new organ to form a secondary tumor, restoring some of their original epithelial traits through mesenchymal-epithelial transition (MET) [3,49]. The metastatic cascade concludes when the cells undergo MET and initiate angiogenesis to ensure adequate nutrient supply in their new environment (Figure 2) [52]. As every step in this cascade is essential for successful metastasis, it is crucial to understand the contribution of individual Wnt ligands throughout this process (Table 1).

Figure 2. The metastatic cascade and the Wnt ligands involved. (1) Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT). (2) Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) production. (3) Cell motility. (4) Angiogenesis. (5) Anoikis resistance. (6) Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition (MET). *Wnt11 has been implicated in vasculogenesis, a similar process to angiogenesis.

|

Metastatic Cascade Component |

Wnt Ligands |

|

Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition |

Wnt1, Wnt2, Wnt2b, Wnt3, Wnt3a, Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt5b, Wnt6, Wnt7a, Wnt7b, Wnt8b, Wnt9a, Wnt10a, Wnt10b, Wnt11, Wnt16 |

|

Matrix Metalloproteinase Production |

Wnt3a, Wnt5b, Wnt7a, Wnt10b |

|

Cell Motility |

Wnt1, Wnt2, Wnt2b, Wnt3, Wnt3a, Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt5b, Wnt6, Wnt7a, Wnt7b, Wnt8a, Wnt8b, Wnt9a, Wnt9b, Wnt10a, Wnt10b, Wnt11 |

|

Anoikis Resistance |

Wnt11 |

|

Mesenchymal-to-epithelial transition |

Wnt2b |

|

Angiogenesis |

Wnt2, Wnt2b, Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt5b, Wnt9b, Wnt10a, Wnt11 |

Canonical Wnt Ligands Involved in Metastasis

The canonical Wnt ligands, Wnt1, Wnt3, Wnt3a, Wnt8a, Wnt8b, and Wnt10b, have all been implicated in promoting the metastatic process. However, some are better studied than others and have been investigated in varying contexts. Future studies are needed to strengthen these associations, as well as to identify unique functions of individual ligands. For example, all of the canonical Wnt ligands have been implicated in the migration and/or invasion of cancer cells, but only Wnt8a has not been implicated in EMT, and only Wnt3a and Wnt10b have been associated with MMP production. Similarly, only Wnt1 has been implicated in the bone metastatic niche. Thus, while the canonical Wnt ligands share many metastatic roles, there remain striking differences that are only just beginning to be identified.

Wnt1

Wnt1, a pro-metastatic Wnt ligand, is unique among the Wnt ligands as a member of the WNT-inducible signaling pathway proteins (WISPs) [53], which are well-established contributors to metastasis. Herein, we will focus on recent advances in understanding Wnt1’s specific roles, distinct from the broader pro-metastatic functions of WISPs [53]. Overexpression of Wnt1 in tumor cells is linked to invasion and metastasis and/or EMT in a number of cancers, including hepatocellular carcinoma, kidney cancer, osteosarcoma, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, and breast cancer [54–64]. Pro-tumor M2-like macrophages have also been shown to secrete Wnt1, and coculture of these macrophages with tumor cells exhibits enhanced migration and invasion [65]. However, most studies of Wnt1 have been conducted in vitro, with a lack of critical in vivo studies across cancers. Despite the lack of research in this area, studies have highlighted a potential mechanism for Wnt1 in breast cancer bone metastases. A recent study suggests that Wnt1 plays a crucial role for osteoblastic bone metastasis. When breast cancer cells overexpressing Wnt1, Wnt3a, and Wnt5a are intracardially injected into mice, only the mice receiving the Wnt1-overexpressing cells develop osteoblastic bone metastases [66]. These mice are also the only ones that show activation of Special AT-Rich Sequence-Binding Protein 2 (SATB2), an osteoblast differentiation marker that promotes osteogenesis [66]. Future studies on the role of Wnt1 in metastasis will further elucidate its specific contributions to the bone metastatic niche across multiple cancers.

Wnt3 and Wnt3a

Wnt3, a pro-metastatic Wnt ligand, is overexpressed in tumor cells and implicated in the metastatic phenotype of many cancers, including non-small cell lung cancer, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and pancreatic adenocarcinoma [67–70]. Its overexpression is associated with enhanced migration and invasion in colorectal cancer [71], gastric cancer [72], breast cancer [73,74], oral cancer [75], and non-small cell lung cancer [70]. Wnt3 is also implicated in promoting EMT in colorectal cancer [71], breast cancer [73], and oral cancer [75]. In vitro studies using human lung and pancreatic adenocarcinoma cells show that mesenchymal-transitioned tumor cells secrete Wnt3, inducing invasion and metastasis in other nearby epithelial cancer cells [69]. Finally, clinical studies confirm the association between Wnt3 and metastasis; Wnt3 is strongly expressed in colorectal adenocarcinoma with liver metastasis and in breast cancer with lymph node, liver, and brain metastases [71,73]. While these studies provide strong evidence for the role of tumor-produced Wnt3 in metastasis, the contribution of stromal or immune-derived Wnt3 in the tumor microenvironment remains unknown.

Wnt3a is the quintessential canonical Wnt ligand and there is a substantial amount of research linking Wnt3a and metastasis. It is produced not only by tumor cells, but by pancreatic stellate cells [76], CAFs [77,78], and TAMs [65,79]. In vitro studies show that Wnt3a expression enhances cellular migration, invasion, and EMT in osteosarcoma, breast cancer, chondrosarcoma, cervical cancer, and hepatocellular carcinoma [80-85]. Moreover, Wnt3a overexpression is associated with increased migration, invasion, and EMT in colorectal cancer cells, and increased production of MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-7 in hepatocellular carcinoma [86-89]. Despite these in vitro and correlative patient studies, that role of Wnt3a induced production of MMPs has not been thoroughly investigated using in vivo models [88,89]. Strong in vivo evidence linking Wnt3a and metastasis comes from studies in lung and gastric cancer. In non-small cell lung cancer, in vitro studies show that increased Wnt3a expression promotes EMT and cellular invasion, while in vivo xenograft murine models show that Wnt3a expression enhances distal metastasis [90–92]. Additionally, overexpression of Wnt3a increases lung and abdominal metastasis in murine gastric cancer models [93,94]. In patient cohorts, elevated Wnt3a expression correlates with lymph node metastasis in patients with laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma [95].

Wnt8a/b

Wnt8a and Wnt8b are understudied Wnt ligands in the context of metastasis [96]. One study in pancreatic cancer indicates that inhibiting Wnt8a decreases cancer cell migration and invasion [97]. Limited evidence indicates that Wnt8b promotes EMT, migration, and invasion in gastric cancer and non-small cell lung cancer [98,99]. Additional studies are required to confirm their pro-metastatic roles.

Wnt10b

Wnt10b is produced both by tumor cells and CAFs [100–102]. While studies of this ligand are limited, Wnt10b has been investigated across a wide variety of cancers and linked to a pro-metastatic phenotype in hepatocellular carcinoma, thyroid cancer, glioblastoma, gastric cancer, and breast cancer, among others [103–108]. In prostate cancer, Wnt10b expression is elevated in metastatic tumors compared to primary tumors, and cultured prostate cancer cells overexpressing Wnt10b exhibit increased motility and invasion [109,110]. Conversely, Wnt10b knockdown reduces MMP-9 and EMT gene expression [109]. Additional studies are needed to clarify the mechanisms underlying Wnt10b’s role in metastasis.

Non-Canonical Wnt Ligands Involved in Metastasis

The non-canonical Wnt ligands—Wnt4, Wnt5a, and Wnt11—are implicated in metastasis, but their roles vary: while all are linked to EMT, cell motility, and angiogenesis, Wnt11 may also exhibit anti-metastatic effects [111]. Despite Wnt5a being the quintessential non-canonical Wnt ligand, recent findings identify unique roles for the other non-canonical ligands and highlight Wnt4’s role in hypoxia-induced endosomes, and Wnt11’s contribution to anoikis resistance [112–114].

Wnt4

Wnt4 is a pro-metastatic Wnt ligand that is produced by both tumor cells and CAFs. In ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma metastases, Wnt4 expression in CAFs is over 10?fold higher than in other cell types within the metastatic tumor microenvironment [27]. Expression analysis of FZD8, LRP5, and LRP6 in the TME suggests that the tumor cells themselves are the primary target of Wnt4, although functional assays are needed to confirm this interaction [27].

Wnt4 expression is linked to enhanced migration and invasion in laryngeal carcinoma [115] and hepatocellular carcinoma [116], and with EMT in hepatocellular carcinoma [116] and colorectal cancers [117]. Limited in vivo studies associate Wnt4 expression with lymph node metastasis in laryngeal carcinoma [115]; however, the strongest in vivo evidence connects Wnt4 to hypoxia-driven metastasis. Hypoxia in primary tumors is a significant driver of metastasis, and expression of Wnt4 has been identified as one mechanism driving this process. In colorectal cancer, hypoxia triggers the release of Wnt4 enriched endosomes [113,114], which are absent in non-hypoxic tumor cells [113]. These Wnt4 enriched endosomes promote the proliferation, migration, and invasion of non-hypoxic tumor cells in vitro and promote metastasis and increase angiogenesis in vivo [113,114]. Future studies are needed to determine if these findings extend to hypoxia-driven metastasis in other cancers.

Wnt5a

Wnt5a is the most extensively studied Wnt ligand for its role in metastasis, with several reviews detailing its significance [118–121]. Herein, we will focus on major findings from the last five years on the role of Wnt5a in the metastatic cascade. Wnt5a is widely recognized as pro-metastatic, with its production reported in tumor cells [122], myeloid-derived suppressor cells [123], CAFs [124-128], and TAMs [129,130]. In fact, despite the fact that both tumor and CAF-secreted Wnt5a contribute to a pro-metastatic phenotype, a recent study implicates TAMs as the primary source of Wnt5a in the microenvironment, rather than the tumor itself, in colorectal cancer [130–133]. The role of TAM-secreted Wnt5a is unexplored in other cancer types, making it a promising avenue for future studies.

Additionally, recent in vitro studies show Wnt5a expression enhances EMT, cellular migration, and invasion in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, osteosarcoma, and liver cancer [134–139]. Elevated Wnt5a expression in patient samples is associated with increased lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma, bladder cancer, and thyroid cancer [140–143]. Murine models also demonstrate the role of Wnt5a in promoting lung cancer metastasis to the brain, and kidney cancer metastasis to the lung and liver [144–147]. Interestingly, Wnt5a can also modulate angiogenesis in kidney cancer and in gliomas [146,148]. In prostate cancer, where bone metastasis poses a significant clinical challenge, bone metastases exhibit the highest Wnt5a expression compared to other metastatic sites. These bone metastases also show the lowest degree of Wnt5a methylation, even when compared to other metastases in the same patient. This hypomethylation allows for increased Wnt5a expression, promoting metastasis and tumor outgrowth [149]. As Wnt5a may drive specific organ-tropic metastasis across various cancers, investigating its methylation patterns in these contexts could be a promising avenue for future research.

Finally, while Wnt5a has already been implicated across the metastatic cascade, it has recently been recognized for its role at the leading edge of tumors. In breast cancer, Wnt5a mediates invasion by inducing CXCL8 and promoting the formation of actin protrusions [150,151]. Elevated Wnt5a secretion from breast cancer cells at the leading edge promotes increased Wnt/PCP signaling, which is essential for proper actin cytoskeleton dynamics supporting these protrusions [151]. Similarly, in melanoma, Wnt5a increases invasion by interacting with myristoylated alanine-rich c-kinase substrate (MARCKS) to drive an invasive phenotype [152–154]. Activated MARCKS, essential for melanoma cell invasion, is directly activated by Wnt5a, which induces accumulation of phosphorylated-MARCKS along the leading edge [154]. A Wnt5a gradient may further guide the direction of the invasive edge. In ovarian cancer, expression of receptor tyrosine kinase?like orphan receptor 2 (ROR2) promotes directed cell migration towards areas with a high concentration of Wnt5a [155]. These findings highlight Wnt5a as a leading pro-metastatic Wnt ligand and serve as a model for studying other non-canonical Wnts.

Wnt11

Wnt11 has been extensively studied in the context of metastasis, but its role as pro- or anti-metastatic remains unclear. Produced exclusively by tumor cells, Wnt11 exhibits pro-metastatic functions in cervical cancer, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and melanoma [156–158]. In prostate cancer, elevated Wnt11 expression enhances migration, invasion, and EMT markers, while Wnt11 inhibition reverses these effects [159–163]. Clinically, metastatic prostate cancers show higher Wnt11 expression than normal prostate or non-metastatic tumors [162,163]. Similarly, in colorectal cancer, high Wnt11 expression is observed in liver metastasis, and its upregulation promotes migration and invasion in vitro and increases lung metastasis in vivo following intravascular injection [164–166]. Inhibition of Wnt11 diminishes these enhanced capabilities [165].

In breast cancer and melanoma, Wnt11 has been extensively studied for its role in metastasis through diverse mechanisms. In breast cancer cells, Wnt11 enhances protrusive activity and motility through Wnt11-FZD6 interactions at the leading edge of cell protrusions [167]. Similarly, in melanoma, Wnt11 regulates invasion and distant metastasis through amoeboid melanoma cells at the tumor’s invasive front [168]. Wnt11 also interacts with ROR2, where increased ROR2 expression correlates with a more invasive phenotype and worse metastasis-free survival in breast cancer [169]. Further, Wnt11 promotes GTPase RhoA activation, conferring anoikis resistance to breast cancer cells [112]. Finally, in melanoma, silencing Wnt11 disrupts vasculogenesis [170], a non-traditional form of blood vessel formation that supports tumor progression and metastatic lesion growth, similar to angiogenesis [170]. Given the diverse mechanisms observed across cancer types, future research should explore whether specific metastatic strategies are conserved across other Wnt11-expressing cancers.

Although Wnt11 is typically considered pro-metastatic, a study in ovarian cancer discovered that high Wnt11 expression inhibits cellular migration, invasion, and intraperitoneal metastasis in a murine model [111]. This finding highlights the need for further investigation into the distinct mechanisms of Wnt11 in ovarian cancer, and whether similar mechanisms occur in other understudied cancers.

Mixed Canonical/Non-Canonical Wnt Ligands Involved in Metastasis

The majority of Wnt ligands, including Wnt2, Wnt2b, Wnt5b, Wnt6, Wnt7a, Wnt7b, Wnt9a, Wnt9b, Wnt10a, and Wnt16, can be classified as both canonical and non-canonical ligands. Due to the large number of ligands in this group, their roles in metastasis vary significantly, with numerous conflicting findings, as discussed below.

Wnt2 and Wnt2b

Wnt2, typically classified as a canonical Wnt ligand, has recently been implicated in non-canonical signaling [171–176]. Irrespective of its canonical or non-canonical activities, Wnt2 is considered pro-metastatic. Wnt2 is produced by tumor cells [177,178], pancreatic stellate cells [174,175], and CAFs across many cancer types [26,179,180]. Wnt2 is linked to invasion and metastasis in lung cancer, endometrial cancer, cervical cancer, pancreatic cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, and colorectal cancer [171–173,176]. In colorectal cancer, Wnt2 may promote angiogenesis; co-culture of endothelial cells with Wnt2-expressing colonic CAFs, compared to Wnt2-knockout CAFs, increases vessel area, branch points, sprouts, and sprout length. Additionally, colorectal tumors overexpressing Wnt2 exhibit enhanced vasculature when subcutaneously injected into mice, compared to control tumors [179]. Wnt2 is also implicated in gastric cancer metastasis [181–185]. A study by Cao and colleagues shows that intravenous injection of Wnt2-overexpressing gastric cancer cells in mice increases lung metastasis in vivo [185]. Further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanism of Wnt2 in lung metastasis.

Wnt2b, also known as Wnt13, is implicated in the metastatic potential of a large number of cancers across multiple steps of the metastatic cascade. Produced by tumor cells, its expression in stromal and immune cells remains unexplored. Wnt2b overexpression has been linked to EMT in multiple cancers, including prostate cancer [186], hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma [187], ovarian cancer [188,189], and cervical cancer [190]. Studies in ovarian and cervical cancer also associate Wnt2 with migration, invasion, EMT, and angiogenesis in vitro [188–190]. Schwab et al. demonstrates Wnt2b’s role in MET in colorectal cancer using the LIM1863-Mph model system, which exhibits epithelial-mesenchymal state plasticity. Wnt2b is the most abundant differentially expressed Wnt gene between epithelial and mesenchymal states, and recombinant Wnt2b overcomes porcupine-inhibitor-blocked MET [191]. In patient studies, Wnt2b has been shown to play a role in perineural spread and lymph node metastasis. Pancreatic cancer is one of the few cancers in which metastatic spread can occur along nerves, and Wnt2b expression is significantly correlated with perineural metastasis, although the mechanism is poorly understood [192]. Additionally, Wnt2b expression also correlates with lymph node metastasis in gallbladder carcinoma [193], osteosarcoma [194], and nasopharyngeal carcinoma [195].

Wnt5b

Wnt5b is implicated in the metastatic phenotype of several cancers, including lung cancer, osteosarcoma, and colorectal cancer [196–200]. Wnt5b production is attributed exclusively to tumor cells [69,201], but Wnt5b can modulate signaling in stromal cells. For example, secreted Wnt5b transforms CAFs into lipid-rich CAFs, which produce vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGFA) to initiate angiogenesis in colon cancer progression and metastasis [142].

Recent advancements in understanding Wnt5b have focused on hepatocellular and breast carcinoma. In hepatocellular carcinoma, patient tissue and in vitro protein analysis reveal that high Wnt5b expression correlates with metastasis, with tissues showing elevated EMT marker expression [202,203]. A similar pattern is observed in breast cancer, where Wnt5b overexpression is linked to a mesenchymal phenotype and stemness. Knocking down Wnt5b in breast cancer cells disrupts these traits [204,205]. In triple-negative breast cancer, high Wnt5b expression strongly correlates with metastasis in patients, and knocking down Wnt5b in immortalized human breast cancer cell lines reduces cellular migration capacity [204].

Finally, recent findings implicate Wnt5b in multiple stages of the metastatic cascade. For example, in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, upregulated Wnt5b enhances migration, invasion, and MMP-10 expression [48]. Similarly, in oral squamous cell carcinoma, elevated Wnt5b promotes migration, lymphatic metastasis, and lymphangiogenesis [206,207]. Notably, Wnt5b knockdown in oral squamous cell carcinoma reduces metastatic spread without impacting primary tumor growth [207], suggesting that, in this tumor model, the role of Wnt5a may be primarily confined to promotion of metastasis.

Wnt6 and Wnt16

Wnt6 is produced by tumor cells [208–211] and hepatic stellate cells [212,213] and is well-established in initiating and promoting EMT [214,215]. Wnt6 has primarily been studied in breast cancer and has been proposed to enhance the migratory and metastatic potential of breast cancer cells [208,216]. One study found that Wnt6 expression correlates with breast cancer metastasis to the bone, although the underlying mechanism remains unclear [209]. Emerging evidence highlights Wnt6 as a potential prognostic biomarker. In osteosarcoma, high Wnt6 expression correlates with higher-grade tumors, increased distant metastasis, and reduced overall survival [210]. Similarly, in colorectal cancer patients with liver metastasis post-hepatic resection, elevated Wnt6 expression is associated with lower overall survival [211]. These findings support Wnt6’s potential as a clinical prognostic biomarker.

In contrast, Wnt16 has been minimally studied in the context of metastasis. It is associated with EMT in retinoblastoma, but its role in metastasis across other cancer types remains unexplored [217].

Wnt7a

Wnt7a is recognized as pro-metastatic across multiple cancer types. For example, in pancreatic cancer and oral squamous cell carcinoma, elevated Wnt7a expression positively correlates with lymph node metastasis, promotes EMT, and enhances cellular migration and invasion [218–220]. Moreover, Wnt7a contributes to extracellular matrix degradation, with increased Wnt7a levels in bladder cancer clinically associated with higher MMP-10 expression [221]. Additionally, Wnt7a has been proposed to support a pro-metastatic role by activating CAFs, in the tumor microenvironment, as observed in breast cancer and ovarian cancer [29,222].

While most studies support Wnt7a’s pro-metastatic role, its function remains controversial. In gastric cancer, Wnt7a overexpression suppresses invasion and metastasis both in vitro and in vivo [223]. Further, although Wnt7a induces MMP-10 expression in bladder cancer, it represses MMP-9 production in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma [221,224], highlighting cancer-type-specific effects. These contradictory findings complicate the study of Wnt7a in complex models. For example, in endometrial cancer, two studies from two different research groups at the same medical center, using similar clinical immunohistochemistry but different antibodies, report opposing correlation between Wnt7a and lymph node metastasis [225,226]. Similarly, contradictory findings exist in colorectal cancer regarding the impact of Wnt7a on lymph node metastasis [227–229]. These discrepancies suggest that Wnt7a’s role may be context-dependent or isoform-dependent. Supporting this idea, a murine breast cancer model identified two Wnt7a isoforms: a 349 amino acid isoform that promotes tumor growth and metastasis and a 148 amino acid isoform that inhibits both [230]. The role of Wnt7a isoforms in human cancer models remains unexplored but warrants further investigation to clarify Wnt7a’s complex role in metastasis.

Wnt7b

Wnt7b exhibits both pro- and anti-metastatic properties, and is produced by both tumor cells and TAMs. It is pro-metastatic in breast cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, and oral squamous cell carcinoma [231–235]. Recent studies in colorectal cancer show conflicting roles, with Wnt7b both promoting and inhibiting metastasis [236,237]. Preliminary research in prostate cancer cells expressing Wnt7b shows increased motility and invasion [110], while its knockdown in lung adenocarcinoma reduces migration and invasion, suggesting a pro-metastatic role in both cancers [238]. However, these findings are limited to in vitro studies and await in vivo validation.

Despite studies linking Wnt7b to cancer cell migration, a recent study in bladder urothelial carcinoma reveals anti-metastatic properties. Wnt7b is commonly downregulated in urothelial carcinoma, but its forced overexpression inhibits EMT and stemness, suggesting an anti-metastatic role [239]. Conversely, in upper tract urothelial carcinoma, Wnt7b expression correlates positively with metastasis [240]. Given that both cancers originate from the same urothelial cell type, these conflicting findings challenge the idea that Wnt7b’s effects are solely cancer-type specific. Future studies should explore the mechanism and regulation of Wnt7b in urothelial cancer and other cancers where Wnt7b may exhibit anti-metastatic properties.

Wnt9a/b

Wnt9a, also known as Wnt14, is a dual canonical and non-canonical Wnt ligand [241] produced by tumor cells. Its role in metastasis is conflicting, with evidence suggesting both anti- and pro-metastatic effects. In breast and colorectal cancer, Wnt9a induction suppresses cellular proliferation, and is downregulated in human bladder carcinoma samples [241–243]. In prostate cancer, Wnt9a enhances metastatic potential by promoting cellular plasticity and EMT marker expression [244]. In vitro, prostate cancer cells overexpressing Wnt9a exhibit enhanced motility and invasion, an effect mitigated by prohibitin, a tumor suppressor that negatively regulates Wnt9a [110]. Further, across patient samples, Wnt9a expression is statistically higher in metastatic prostate cancer compared to non-metastatic prostate cancer or benign prostate [110]. The conflicting roles of Wnt9a in metastasis warrant further investigation.

Wnt9b, also known as Wnt14b and Wnt15, is understudied in the context of metastasis. Its mechanism has only been reported in cervical cancer and glioblastoma [245,246]. In cervical cancer, Wnt9b expression promotes cellular proliferation, migration, and invasion, whereas in glioblastoma Wnt9b expression is associated with angiogenesis [245,246]. In breast cancer, Wnt9b serves as a sensitive and specific diagnostic marker in surgical pathology [247–249], but its role in breast cancer metastasis remains largely unexplored.

Wnt10a

Wnt10a exhibits pro-metastatic roles, and when produced by tumor cells, promotes migration and invasion in renal cell carcinoma, papillary thyroid cancer [250–253], breast cancer [254,255], and esophageal squamous cell carcinoma [256]. Notably, in 3D-organotypic cultures of invasive esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, Wnt10a expression is upregulated over four-fold at the invasive front, compared to the rest of the culture [256]. Additionally, Wnt10a overexpression induces EMT and angiogenesis in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma [257] and correlates with lymph node metastasis in breast cancer patients [255]. Future studies are needed to build upon these findings.

Targeting the Wnt Pathway in Metastasis

Given that Wnt ligands play a crucial role in the metastatic cascade across cancers, targeting the Wnt pathway serves as an appealing strategy for reducing cancer progression (Table 2). However, not all Wnt ligands are strictly pro-metastatic, and conflicting data for mixed canonical and non-canonical ligands highlight the need for further studies to clarify their potential for therapeutic targets. Overall, canonical Wnt ligands are the most well-studied and consistently pro-metastatic, and thus, represent promising targets for reducing cancer spread.

|

Wnt Ligand |

Canonical or Non-Canonical |

Pro-Metastatic |

Anti-Metastatic |

References |

|

Wnt1 |

Canonical |

Hepatocellular carcinoma, osteosarcoma, Wilm’s tumor, colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, breast cancer |

None |

[28–40] |

|

Wnt2 |

Both |

Lung adenocarcinoma, endometrial cancer, cervical cancer, pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma |

None |

[13,151–159] |

|

Wnt2b |

Both |

Prostate cancer, hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma, ovarian cancer, cervical cancer, colorectal cancer, pancreatic cancer, osteosarcoma, gallbladder cancer |

None |

[160–169] |

|

Wnt3 |

Canonical |

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, pancreatic cancer, colorectal cancer, gastric cancer, breast cancer, non- small cell lung cancer, oral squamous cell carcinoma |

None |

[41–49] |

|

Wnt3a |

Canonical |

Osteosarcoma, breast cancer, chondrosarcoma, cervical cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal cancer, non- small cell lung cancer, gastric cancer, laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma |

None |

[39,50–69] |

|

Wnt4 |

Non-canonical |

Ovarian cancer, laryngeal carcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, colorectal cancer |

None |

[14, 87–91] |

|

Wnt5a |

Non-canonical |

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, osteosarcoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatoblastoma, oral squamous cell carcinoma, bladder cancer, thyroid cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, non- small cell lung cancer, renal cell carcinoma, glioma, prostate cancer, breast cancer, melanoma, ovarian cancer |

None |

[96–129] |

|

Wnt5b |

Both |

Lung adenocarcinoma, non-small cell lung cancer, osteosarcoma, colorectal cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, oral squamous cell carcinoma |

None |

[22,43,142,170–181] |

|

Wnt6 |

Both |

Breast cancer, osteosarcoma, colorectal cancer |

None |

[182–190] |

|

Wnt7a |

Both |

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, oral squamous cell carcinoma, bladder cancer, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, colorectal cancer, endometrial cancer |

Gastric cancer, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, endometrial cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer |

[16,192–204] |

|

Wnt7b |

Both |

Breast cancer, gastric cancer, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, hepatocellular carcinoma, oral squamous cell carcinoma, colorectal cancer, prostate cancer, lung adenocarcinoma, upper tract urothelial carcinoma |

Colorectal cancer, bladder, cancer, urothelial carcinoma |

[84,205–214] |

|

Wnt8a |

Canonical |

Pancreatic cancer |

None |

[71] |

|

Wnt8b |

Canonical |

Gastric cancer, non-small cell lung cancer |

None |

[72,73] |

|

Wnt9a |

Both |

Prostate cancer |

Breast cancer, colorectal cancer, bladder cancer |

[84, 215–218] |

|

Wnt9b |

Both |

Cervical cancer, glioblastoma |

None |

[219–223] |

|

Wnt10a |

Both |

Renal cell carcinoma, thyroid cancer, breast cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma |

None |

[224–231] |

|

Wnt10b |

Canonical |

Hepatocellular carcinoma, thyroid cancer, glioblastoma, gastric cancer, breast cancer, prostate cancer |

None |

[74–84] |

|

Wnt11 |

Non-canonical |

Cervical cancer, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, prostate cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, melanoma |

Ovarian cancer |

[85,86,130–144] |

|

Wnt16 |

Both |

Retinoblastoma |

None |

[191] |

One approach to target Wnt signaling in the setting of metastasis is to block the secretion of Wnt ligands or the activation of specific Wnt receptors. This approach could be accomplished with broadly acting porcupine inhibitors. Porcupine is an acetyltransferase that promotes the palmitoylation of Wnt ligands at the cell membrane, allowing for the secretion of Wnt ligands [258]. Without activity of the porcupine protein, Wnt ligand secretion and local Wnt signaling is disrupted [259]. While small molecule porcupine inhibitors have been developed, they target the Wnt pathway broadly, including ligands that affect both non-canonical and canonical pathways. Because of this lack of specificity, they exhibit toxicities, most notably that of decreased bone mass [260].

In addition to porcupine inhibitors, Frizzled receptor inhibitors have recently been developed. Both small molecule drugs and monoclonal antibodies have been developed that can inhibit specific Frizzled receptors [261–263]. Each Wnt ligand has a different affinity for the various Frizzled receptors [264]. Therefore, it is possible to reduce the activity of a specific Wnt ligand by inhibiting its major Frizzled receptor. For example, Wnt2 is associated with increased aggression in thyroid cancer [4] and strongly stimulates Frizzled 8 receptors [265]. Hence, a potential treatment for thyroid cancer progression could be the use of an anti-Frizzled 8 antibody. The varied expression and specificities of Frizzled receptors may explain the organ-specific dependency on certain Wnt ligands. Moreover, combining these Frizzled receptor inhibitors with a low dose porcupine inhibitor may reduce toxicity and improve outcomes.

Additionally, with the use of Frizzled receptor inhibitors it may be possible to target both 1) receptors important for the tumor’s growth and proliferation at the primary tumor site and 2) receptors expressed in metastatic niches that may promote cancer cell colonization. For example, late stage colon cancers frequently express Wnt5a and Wnt5b, and their cognate receptor Frizzled 2 [266]. As the expression of these ligands and receptors also occurs in the lungs [267], a common metastatic site for colon cancer, treatment with an anti-Frizzled 2 antibody could inhibit both primary tumor growth and metastatic outgrowth in the lungs. Future studies should work to further dissect the roles of Wnt ligands and metastasis, as well as the efficacy of various Wnt inhibitors, as this treatment strategy has the potential to help many patients across cancer types worldwide.

Finally, it is also important to consider the impact that targeting Wnt may have on the tumor microenvironment due to the large involvement of Wnt in the TME as well as the tumor itself [268–270]. Wnt signaling can lead to epigenetic alterations in the TME which could make tumors more or less resistant to treatment, though the consequences of these alterations need further investigation [271,272]. Moreover, Wnt can significantly modulate the immune system [269]. For example, it has been shown that various Wnt ligands can polarize TAMs into either an anti-tumorigenic ‘M1-like’ state, or a pro-tumorigenic ‘M2-like’ state [273]. Wnt signaling is also important for the differentiation and activation of cytotoxic T cells [269]. Additionally, some Wnt signaling components when overexpressed by tumor cells can be recognized as tumor-associated antigens, thereby triggering tumor cell killing by immune cells [274]. These findings could suggest that targeting Wnt signaling may be a poor approach to take as it could negatively suppress the body’s natural immune response to tumors. However, other research has shown that Wnt signaling promotes immune exclusion, as well as dampens dendritic cell-priming of anti-tumor T cells [269,274]. This would suggest that targeting Wnt signaling would bolster the immune response, making treatment even more effective, especially in combination with other treatments such as immunotherapy. Thus, future studies should also work to dissect the role of Wnt in the TME in distinct tumor settings to best inform the use of Wnt inhibition as a treatment strategy to have the largest positive impact on patients globally.

Conclusion

Metastasis, a devastating hallmark of cancer, significantly reduces patient survival, underscoring the need to better understand its drivers to improve outcomes. Wnt ligands and Wnt signaling play crucial roles in numerous biological processes, including metastasis. Currently, research identifies Wnt1, Wnt2, Wnt2b, Wnt3, Wnt3a, Wnt4, Wnt5a, Wnt5b, Wnt6, Wnt8a, Wnt9b, Wnt10a, Wnt10b, and Wnt16 as pro-metastatic Wnt ligands, while Wnt7a, Wnt7b, Wnt8b, Wnt9a, and Wnt11 exhibits conflicting pro- and anti-metastatic roles. Recent studies show that these ligands can originate from tumor cells or microenvironmental cells, such as fibroblasts and macrophages. However, the role of Wnt ligands in metastasis remains incompletely understood. Future studies are needed to deepen our understanding of the relevant mechanisms in both primary and metastatic tumors. Such insights will pave the way for novel therapeutic strategies to alleviate the burden of metastatic disease.

Conflict of Interest

E.L. is a co-founder of StemSynergy Therapeutics, a company that seeks to develop inhibitors of major signaling pathways (including the Wnt pathway) for the treatment of cancer. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants: T32ES007028 to K.P.C.; T32GM007347 to J.B.T; R35GM122516, R01CA281002, and 2P50CA236733 to EL; K08CA240901 and R01CA272875 to V.L.W.

Acknowledgements

The figures for this work were created using BioRender.com. Figure 1: Created in BioRender. Caroland, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/6kp7i8y and https://BioRender.com/m8p9m50. Figure 2: Created in BioRender. Caroland, K. (2025) https://BioRender.com/oi0rjb9.

Author Contributions

Writing original draft preparation and editing, K.P.C., J.B.T., E.L., and V.L.W. Graphic conception, drawing, and editing, K.P.C. and V.L.W. Overall supervision, E.L. and V.L.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

References

2. Welch DR, Hurst DR. Defining the Hallmarks of Metastasis. Cancer Res. 2019;79(12):3011–27.

3. Fares J, Fares MY, Khachfe HH, Salhab HA, Fares Y. Molecular principles of metastasis: a hallmark of cancer revisited. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5(1):28.

4. Diaz D, Bergdorf K, Loberg MA, Phifer CJ, Xu GJ, Sheng Q, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling is a therapeutic target in anaplastic thyroid carcinoma. Endocrine. 2024;86(1):114–8.

5. Hartmann HA, Loberg MA, Xu GJ, Schwarzkopf AC, Chen SC, Phifer CJ, et al. Tenascin-C Potentiates Wnt Signaling in Thyroid Cancer. Endocrinology. 2025;166(3):bqaf030.

6. Chen H, Wang Y, Xue F. Expression and the clinical significance of Wnt10a and Wnt10b in endometrial cancer are associated with the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Oncol Rep. 2013;29(2):507–14.

7. Qin K, Yu M, Fan J, Wang H, Zhao P, Zhao G, et al. Canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling: Multilayered mediators, signaling mechanisms and major signaling crosstalk. Genes Dis. 2024;11(1):103–34.

8. Werner J, Boonekamp KE, Zhan T, Boutros M. The Roles of Secreted Wnt Ligands in Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(6):5349.

9. Mosby LS, Bowen AE, Hadjivasiliou Z. Morphogens in the evolution of size, shape and patterning. Development. 2024;151(18):dev202412.

10. Willert K, Brown JD, Danenberg E, Duncan AW, Weissman IL, Reya T, et al. Wnt proteins are lipid-modified and can act as stem cell growth factors. Nature. 2003;423(6938):448–52.

11. Takada R, Satomi Y, Kurata T, Ueno N, Norioka S, Kondoh H, et al. Monounsaturated fatty acid modification of Wnt protein: its role in Wnt secretion. Dev Cell. 2006;11(6):791–801.

12. Sharma R. Wingless a new mutant in Drosophila melanogaster. Drosophila information service. 1973;50:134.

13. Sharma RP, Chopra VL. Effect of the Wingless (wg1) mutation on wing and haltere development in Drosophila melanogaster. Dev Biol. 1976;48(2):461–5.

14. Rijsewijk F, Schuermann M, Wagenaar E, Parren P, Weigel D, Nusse R. The Drosophila homolog of the mouse mammary oncogene int-1 is identical to the segment polarity gene wingless. Cell. 1987;50(4):649–57.

15. Nusse R, Varmus HE. Many tumors induced by the mouse mammary tumor virus contain a provirus integrated in the same region of the host genome. Cell. 1982;31(1):99–109.

16. Nagafuchi A, Takeichi M. Transmembrane control of cadherin-mediated cell adhesion: a 94 kDa protein functionally associated with a specific region of the cytoplasmic domain of E-cadherin. Cell Regul. 1989;1(1):37–44.

17. Ozawa M, Baribault H, Kemler R. The cytoplasmic domain of the cell adhesion molecule uvomorulin associates with three independent proteins structurally related in different species. EMBO J. 1989;8(6):1711–7.

18. Rubinfeld B, Souza B, Albert I, Muller O, Chamberlain SH, Masiarz FR, et al. Association of the APC gene product with beta-catenin. Science. 1993;262(5140):1731–4.

19. Noordermeer J, Klingensmith J, Perrimon N, Nusse R. dishevelled and armadillo act in the wingless signalling pathway in Drosophila. Nature. 1994;367(6458):80–3.

20. Munemitsu S, Albert I, Souza B, Rubinfeld B, Polakis P. Regulation of intracellular beta-catenin levels by the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor-suppressor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(7):3046–50.

21. Riggleman B, Schedl P, Wieschaus E. Spatial expression of the Drosophila segment polarity gene armadillo is posttranscriptionally regulated by wingless. Cell. 1990;63(3):549–60.

22. Riggleman B, Wieschaus E, Schedl P. Molecular analysis of the armadillo locus: uniformly distributed transcripts and a protein with novel internal repeats are associated with a Drosophila segment polarity gene. Genes Dev. 1989;3(1):96–113.

23. Peifer M, Wieschaus E. The segment polarity gene armadillo encodes a functionally modular protein that is the Drosophila homolog of human plakoglobin. Cell. 1990;63(6):1167–76.

24. McCrea PD, Turck CW, Gumbiner B. A homolog of the armadillo protein in Drosophila (plakoglobin) associated with E-cadherin. Science. 1991;254(5036):1359–61.

25. Holzem M, Boutros M, Holstein TW. The origin and evolution of Wnt signalling. Nat Rev Genet. 2024;25(7):500–12.

26. Aizawa T, Karasawa H, Funayama R, Shirota M, Suzuki T, Maeda S, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts secrete Wnt2 to promote cancer progression in colorectal cancer. Cancer Med. 2019;8(14):6370–82.

27. Sommerfeld L, Finkernagel F, Jansen JM, Wagner U, Nist A, Stiewe T, et al. The multicellular signalling network of ovarian cancer metastases. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11(11):e633.

28. Neophytou CM, Panagi M, Stylianopoulos T, Papageorgis P. The Role of Tumor Microenvironment in Cancer Metastasis: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Opportunities. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(9):2053.

29. Avgustinova A, Iravani M, Robertson D, Fearns A, Gao Q, Klingbeil P, et al. Tumour cell-derived Wnt7a recruits and activates fibroblasts to promote tumour aggressiveness. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10305.

30. Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, Niu C, Li Y, Zhang X, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):3.

31. Hartmann H, Siddiqui GS, Bryant J, Robbins DJ, Weiss VL, Ahmed Y, et al. Wnt signalosomes: What we know that we do not know. Bioessays. 2025;47(2):e2400110.

32. Akoumianakis I, Polkinghorne M, Antoniades C. Non-canonical WNT signalling in cardiovascular disease: mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2022;19(12):783–97.

33. Tsutsumi N, Hwang S, Waghray D, Hansen S, Jude KM, Wang N, et al. Structure of the Wnt-Frizzled-LRP6 initiation complex reveals the basis for coreceptor discrimination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(11):e2218238120.

34. Janda CY, Waghray D, Levin AM, Thomas C, Garcia KC. Structural basis of Wnt recognition by Frizzled. Science. 2012;337(6090):59–64.

35. Qin K, Yu M, Fan J, Wang H, Zhao P, Zhao G, et al. Canonical and noncanonical Wnt signaling: Multilayered mediators, signaling mechanisms and major signaling crosstalk. Genes & Diseases. 2024;11(1):103–34.

36. van Amerongen R. Alternative Wnt pathways and receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(10):a007914.

37. Liu J, Xiao Q, Xiao J, Niu C, Li Y, Zhang X, et al. Wnt/?-catenin signalling: function, biological mechanisms, and therapeutic opportunities. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2022;7(1):3.

38. Bourhis E, Tam C, Franke Y, Bazan JF, Ernst J, Hwang J, et al. Reconstitution of a frizzled8.Wnt3a.LRP6 signaling complex reveals multiple Wnt and Dkk1 binding sites on LRP6. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(12):9172–9.

39. Cheng Z, Biechele T, Wei Z, Morrone S, Moon RT, Wang L, et al. Crystal structures of the extracellular domain of LRP6 and its complex with DKK1. Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. 2011;18(11):1204–10.

40. Yun J, Hansen S, Morris O, Madden DT, Libeu CP, Kumar AJ, et al. Senescent cells perturb intestinal stem cell differentiation through Ptk7 induced noncanonical Wnt and YAP signaling. Nature Communications. 2023;14(1):156.

41. Fernandez A, Huggins IJ, Perna L, Brafman D, Lu D, Yao S, et al. The WNT receptor FZD7 is required for maintenance of the pluripotent state in human embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(4):1409–14.

42. Dijksterhuis JP, Petersen J, Schulte G. WNT/Frizzled signalling: receptor-ligand selectivity with focus on FZD-G protein signalling and its physiological relevance: IUPHAR Review 3. Br J Pharmacol. 2014;171(5):1195–209.

43. Lu W, Yamamoto V, Ortega B, Baltimore D. Mammalian Ryk is a Wnt coreceptor required for stimulation of neurite outgrowth. Cell. 2004;119(1):97–108.

44. Grainger S, Nguyen N, Richter J, Setayesh J, Lonquich B, Oon CH, et al. EGFR is required for Wnt9a–Fzd9b signalling specificity in haematopoietic stem cells. Nature Cell Biology. 2019;21(6):721–30.

45. Ho HY, Susman MW, Bikoff JB, Ryu YK, Jonas AM, Hu L, et al. Wnt5a-Ror-Dishevelled signaling constitutes a core developmental pathway that controls tissue morphogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(11):4044–51.

46. Jorgensen CLT, Forsare C, Bendahl PO, Falck AK, Ferno M, Lovgren K, et al. Expression of epithelial-mesenchymal transition-related markers and phenotypes during breast cancer progression. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;181(2):369–81.

47. Cabral-Pacheco GA, Garza-Veloz I, Castruita-De la Rosa C, Ramirez-Acuna JM, Perez-Romero BA, Guerrero-Rodriguez JF, et al. The Roles of Matrix Metalloproteinases and Their Inhibitors in Human Diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(24):9739.

48. Deraz EM, Kudo Y, Yoshida M, Obayashi M, Tsunematsu T, Tani H, et al. MMP-10/stromelysin-2 promotes invasion of head and neck cancer. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):e25438.

49. Yu RY, Jiang WG, Martin TA. The WASP/WAVE Protein Family in Breast Cancer and Their Role in the Metastatic Cascade. Cancer Genomics Proteomics. 2025;22(2):166–87.

50. Khan SU, Fatima K, Malik F. Understanding the cell survival mechanism of anoikis-resistant cancer cells during different steps of metastasis. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2022;39(5):715–26.

51. Akhtar M, Haider A, Rashid S, Al-Nabet A. Paget's "Seed and Soil" Theory of Cancer Metastasis: An Idea Whose Time has Come. Adv Anat Pathol. 2019;26(1):69–74.

52. Lugano R, Ramachandran M, Dimberg A. Tumor angiogenesis: causes, consequences, challenges and opportunities. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2020;77(9):1745–70.

53. Liu Y, Song Y, Ye M, Hu X, Wang ZP, Zhu X. The emerging role of WISP proteins in tumorigenesis and cancer therapy. J Transl Med. 2019;17(1):28.

54. Ai Y, Luo S, Wang B, Xiao S, Wang Y. MiR-126-5p Promotes Tumor Cell Proliferation, Metastasis and Invasion by Targeting TDO2 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Molecules. 2022;27(2):443.

55. Li Y, Tian Y, Zhong W, Wang N, Wang Y, Zhang Y, et al. Artemisia argyi Essential Oil Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma Metastasis via Suppression of DEPDC1 Dependent Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:664791.

56. Zhou N, Yan B, Ma J, Jiang H, Li L, Tang H, et al. Expression of TCF3 in Wilms' tumor and its regulatory role in kidney tumor cell viability, migration and apoptosis in vitro. Mol Med Rep. 2021;24(3):642.

57. Chen X, Zhang Y, Zhang S, Wang A, Du Q, Wang Z. Oleanolic acid inhibits osteosarcoma cell proliferation and invasion by suppressing the SOX9/Wnt1 signaling pathway. Exp Ther Med. 2021;21(5):443.

58. Zhang H, Li Z, Jiang J, Lei Y, Xie J, Liu Y, et al. SNTB1 regulates colorectal cancer cell proliferation and metastasis through YAP1 and the WNT/beta-catenin pathway. Cell Cycle. 2023;22(17):1865–83.

59. Huo Y, Wang Y, An N, Du X. [TIM-3 gene is highly expressed in ephithelial ovarian cancer to promote proliferation and migration of ovarian cancer cells]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2022;42(2):190–200.

60. Guo Q, Wang L, Zhu L, Lu X, Song Y, Sun J, et al. The clinical significance and biological function of lncRNA SOCAR in serous ovarian carcinoma. Gene. 2019;713:143969.

61. Cheng Z, Wang H, Yang Z, Li J, Chen X. LMP2 and TAP2 impair tumor growth and metastasis by inhibiting Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway and EMT in cervical cancer. BMC Cancer. 2023;23(1):1128.

62. Xu T, Zeng Y, Shi L, Yang Q, Chen Y, Wu G, et al. Targeting NEK2 impairs oncogenesis and radioresistance via inhibiting the Wnt1/beta-catenin signaling pathway in cervical cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39(1):183.

63. Yang S, Sun S, Xu W, Yu B, Wang G, Wang H. Astragalus polysaccharide inhibits breast cancer cell migration and invasion by regulating epithelial?mesenchymal transition via the Wnt/beta?catenin signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2020;21(4):1819–32.

64. Zhou P, Liu P, Zhang J. Long noncoding RNA RUSC1?AS?N promotes cell proliferation and metastasis through Wnt/beta?catenin signaling in human breast cancer. Mol Med Rep. 2019;19(2):861–8.

65. Lv J, Feng ZP, Chen FK, Liu C, Jia L, Liu PJ, et al. M2-like tumor-associated macrophages-secreted Wnt1 and Wnt3a promotes dedifferentiation and metastasis via activating beta-catenin pathway in thyroid cancer. Mol Carcinog. 2021;60(1):25–37.

66. Sugyo A, Tsuji AB, Sudo H, Sugiura Y, Koizumi M, Higashi T. Wnt1 induces osteoblastic changes in a well-established osteolytic skeletal metastatic model derived from breast cancer. Cancer Rep (Hoboken). 2023;6(12):e1909.

67. Tang Z, Cai H, Wang R, Cui Y. Overexpression of CD300A inhibits progression of NSCLC through downregulating Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:8875–83.

68. Tang Z, Yang Y, Chen W, Liang T. Epigenetic deregulation of MLF1 drives intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma progression through EGFR/AKT and Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Hepatol Commun. 2023;7(8):e0204.

69. Kato S, Hayakawa Y, Sakurai H, Saiki I, Yokoyama S. Mesenchymal-transitioned cancer cells instigate the invasion of epithelial cancer cells through secretion of WNT3 and WNT5B. Cancer Sci. 2014;105(3):281–9.

70. Shukla S, Sinha S, Khan S, Kumar S, Singh K, Mitra K, et al. Cucurbitacin B inhibits the stemness and metastatic abilities of NSCLC via downregulation of canonical Wnt/beta-catenin signaling axis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:21860.

71. Zhuang Y, Zhou J, Liu S, Wang Q, Qian J, Zou X, et al. Yiqi Jianpi Huayu Jiedu Decoction Inhibits Metastasis of Colon Adenocarcinoma by Reversing Hsa-miR-374a-3p/Wnt3/beta-Catenin-Mediated Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition and Cellular Plasticity. Front Oncol. 2022;12:904911.

72. Wang HS, Nie X, Wu RB, Yuan HW, Ma YH, Liu XL, et al. Downregulation of human Wnt3 in gastric cancer suppresses cell proliferation and induces apoptosis. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:3849–60.

73. Gong C, Qu S, Lv XB, Liu B, Tan W, Nie Y, et al. BRMS1L suppresses breast cancer metastasis by inducing epigenetic silence of FZD10. Nat Commun. 2014;5:5406.

74. Yin P, Wang W, Gao J, Bai Y, Wang Z, Na L, et al. Fzd2 Contributes to Breast Cancer Cell Mesenchymal-Like Stemness and Drug Resistance. Oncol Res. 2020;28(3):273–84.

75. Chung PC, Hsieh PC, Lan CC, Hsu PC, Sung MY, Lin YH, et al. Role of Chrysophanol in Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Oral Cancer Cell Lines via a Wnt-3-Dependent Pathway. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2020;2020:8373715.

76. Geleta B, Tout FS, Lim SC, Sahni S, Jansson PJ, Apte MV, et al. Targeting Wnt/tenascin C-mediated cross talk between pancreatic cancer cells and stellate cells via activation of the metastasis suppressor NDRG1. J Biol Chem. 2022;298(3):101608.

77. Du M, Shen P, Tan R, Wu D, Tu S. Aloe-emodin inhibits the proliferation, migration, and invasion of melanoma cells via inactivation of the Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway. Ann Transl Med. 2021;9(23):1722.

78. Sinnberg T, Levesque MP, Krochmann J, Cheng PF, Ikenberg K, Meraz-Torres F, et al. Wnt-signaling enhances neural crest migration of melanoma cells and induces an invasive phenotype. Mol Cancer. 2018;17(1):59.

79. Tian X, Wu Y, Yang Y, Wang J, Niu M, Gao S, et al. Long noncoding RNA LINC00662 promotes M2 macrophage polarization and hepatocellular carcinoma progression via activating Wnt/beta-catenin signaling. Mol Oncol. 2020;14(2):462–83.

80. Xu Z, He W, Ke T, Zhang Y, Zhang G. DHRS12 inhibits the proliferation and metastasis of osteosarcoma via Wnt3a/beta-catenin pathway. Future Oncol. 2020;16(11):665–74.

81. Liu G, Wang P, Zhang H. MiR-6838-5p suppresses cell metastasis and the EMT process in triple-negative breast cancer by targeting WNT3A to inhibit the Wnt pathway. J Gene Med. 2019;21(12):e3129.

82. Le J, Ji H, Pi P, Chen K, Gu X, Ma Y, et al. The Effects and Mechanisms of Sennoside A on Inducing Cytotoxicity, Apoptosis, and Inhibiting Metastasis in Human Chondrosarcoma Cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2022;2022:8063497.

83. Shi F, Wei Y, Huang Y, Yao D. Activating Transcription Factor 5 Promotes Tumorigenic Capability in Cervical Cancer Through the Wnt/beta-Catenin Signaling Pathway. Cancer Manag Res. 2025;17:131–43.

84. Zhang J, Shen Q, Xia L, Zhu X, Zhu X. DYNLT3 overexpression induces apoptosis and inhibits cell growth and migration via inhibition of the Wnt pathway and EMT in cervical cancer. Front Oncol. 2022;12:889238.

85. Du L, Wang L, Yang H, Duan J, Lai J, Wu W, et al. Sex Comb on Midleg Like-2 Accelerates Hepatocellular Carcinoma Cell Proliferation and Metastasis by Activating Wnt/beta-Catenin/EMT Signaling. Yonsei Med J. 2021;62(12):1073–82.

86. Kang AR, Kim JL, Kim Y, Kang S, Oh SC, Park JK. A novel RIP1-mediated canonical WNT signaling pathway that promotes colorectal cancer metastasis via beta -catenin stabilization-induced EMT. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023;30(10):1403–13.

87. Liang J, Sun L, Li Y, Liu W, Li D, Chen P, et al. Wnt signaling modulator DKK4 inhibits colorectal cancer metastasis through an AKT/Wnt/beta-catenin negative feedback pathway. J Biol Chem. 2022;298(11):102545.

88. Quarshie JT, Fosu K, Offei NA, Sobo AK, Quaye O, Aikins AR. Cryptolepine Suppresses Colorectal Cancer Cell Proliferation, Stemness, and Metastatic Processes by Inhibiting WNT/beta-Catenin Signaling. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2023;16(7):1026.

89. Lu C, He Y, Duan J, Yang Y, Zhong C, Zhang J, et al. Expression of Wnt3a in hepatocellular carcinoma and its effects on cell cycle and metastasis. Int J Oncol. 2017;51(4):1135–45.

90. Wu J, Li W, Zhang X, Shi F, Jia Q, Wang Y, et al. Expression and potential molecular mechanism of TOP2A in metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):12228.

91. Song JW, Zhu J, Wu XX, Tu T, Huang JQ, Chen GZ, et al. GOLPH3/CKAP4 promotes metastasis and tumorigenicity by enhancing the secretion of exosomal WNT3A in non-small-cell lung cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2021;12(11):976.

92. Li C, Song G, Zhang S, Wang E, Cui Z. Wnt3a increases the metastatic potential of non-small cell lung cancer cells in vitro in part via its upregulation of Notch3. Oncol Rep. 2015;33(3):1207–14.

93. Liu C, Shen A, Song J, Cheng L, Zhang M, Wang Y, et al. LncRNA-CCAT5-mediated crosstalk between Wnt/beta-Catenin and STAT3 signaling suggests novel therapeutic approaches for metastatic gastric cancer with high Wnt activity. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2024;44(1):76–100.

94. Wang J, Shen D, Li S, Li Q, Zuo Q, Lu J, et al. LINC00665 activating Wnt3a/beta-catenin signaling by bond with YBX1 promotes gastric cancer proliferation and metastasis. Cancer Gene Ther. 2023;30(11):1530–42.

95. Zhang D, Li G, Chen X, Jing Q, Liu C, Lu S, et al. Wnt3a protein overexpression predicts worse overall survival in laryngeal squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer. 2019;10(19):4633–8.

96. Ngernsombat C, Prattapong P, Larbcharoensub N, Khotthong K, Janvilisri T. WNT8B as an Independent Prognostic Marker for Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma. Curr Oncol. 2021;28(4):2529–39.

97. Yao X, Mao Y, Wu D, Zhu Y, Lu J, Huang Y, et al. Exosomal circ_0030167 derived from BM-MSCs inhibits the invasion, migration, proliferation and stemness of pancreatic cancer cells by sponging miR-338-5p and targeting the Wif1/Wnt8/beta-catenin axis. Cancer Lett. 2021;512:38–50.

98. Huang L, Wu RL, Xu AM. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in gastric cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2015;7(11):2141–58.

99. Zhao P, Zhao Q, Chen C, Lu S, Jin L. miR-4757-3p Inhibited the Migration and Invasion of Lung Cancer Cell via Targeting Wnt Signaling Pathway. J Oncol. 2023;2023:6544042.

100. Dai BW, Yang ZM, Deng P, Chen YR, He ZJ, Yang X, et al. HOXC10 promotes migration and invasion via the WNT-EMT signaling pathway in oral squamous cell carcinoma. J Cancer. 2019;10(19):4540–51.

101. Min A, Zhu C, Peng S, Shuai C, Sun L, Han Y, et al. Downregulation of Microrna-148a in Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts from Oral Cancer Promotes Cancer Cell Migration and Invasion by Targeting Wnt10b. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2016;30(4):186–91.

102. Chen Y, Zeng C, Zhan Y, Wang H, Jiang X, Li W. Aberrant low expression of p85alpha in stromal fibroblasts promotes breast cancer cell metastasis through exosome-mediated paracrine Wnt10b. Oncogene. 2017;36(33):4692–705.

103. Zhang S, Xu J, Cao H, Jiang M, Xiong J. KB-68A7.1 Inhibits Hepatocellular Carcinoma Development Through Binding to NSD1 and Suppressing Wnt/beta-Catenin Signalling. Front Oncol. 2021;11:808291.

104. Li C, Chen X, Liu T, Chen G. lncRNA HOTAIRM1 regulates cell proliferation and the metastasis of thyroid cancer by targeting Wnt10b. Oncol Rep. 2021;45(3):1083–93.

105. Li HY, Lv BB, Bi YH. FABP4 accelerates glioblastoma cell growth and metastasis through Wnt10b signalling. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(22):7807–18.

106. Wu XD, Bie QL, Zhang B, Yan ZH, Han ZJ. Wnt10B is critical for the progression of gastric cancer. Oncol Lett. 2017;13(6):4231–7.

107. El Ayachi I, Fatima I, Wend P, Alva-Ornelas JA, Runke S, Kuenzinger WL, et al. The WNT10B Network Is Associated with Survival and Metastases in Chemoresistant Triple-Negative Breast Cancer. Cancer Res. 2019;79(5):982–93.

108. Fatima I, El-Ayachi I, Playa HC, Alva-Ornelas JA, Khalid AB, Kuenzinger WL, et al. Simultaneous Multi-Organ Metastases from Chemo-Resistant Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Are Prevented by Interfering with WNT-Signaling. Cancers (Basel). 2019;11(12):2039.

109. Madueke I, Hu WY, Hu D, Swanson SM, Vander Griend D, Abern M, et al. The role of WNT10B in normal prostate gland development and prostate cancer. Prostate. 2019;79(14):1692–704.

110. Koushyar S, Uysal-Onganer P, Jiang WG, Dart DA. Prohibitin Links Cell Cycle, Motility and Invasion in Prostate Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(12):9919.

111. Azimian-Zavareh V, Hossein G, Ebrahimi M, Dehghani-Ghobadi Z. Wnt11 alters integrin and cadherin expression by ovarian cancer spheroids and inhibits tumorigenesis and metastasis. Exp Cell Res. 2018;369(1):90–104.

112. van de Ven RA, Tenhagen M, Meuleman W, van Riel JJ, Schackmann RC, Derksen PW. Nuclear p120-catenin regulates the anoikis resistance of mouse lobular breast cancer cells through Kaiso-dependent Wnt11 expression. Dis Model Mech. 2015;8(4):373–84.

113. Huang Z, Feng Y. Exosomes Derived From Hypoxic Colorectal Cancer Cells Promote Angiogenesis Through Wnt4-Induced beta-Catenin Signaling in Endothelial Cells. Oncol Res. 2017;25(5):651–61.

114. Huang Z, Yang M, Li Y, Yang F, Feng Y. Exosomes Derived from Hypoxic Colorectal Cancer Cells Transfer Wnt4 to Normoxic Cells to Elicit a Prometastatic Phenotype. Int J Biol Sci. 2018;14(14):2094–102.

115. Wang N, Yan H, Wu D, Zhao Z, Chen X, Long Q, et al. PRMT5/Wnt4 axis promotes lymph-node metastasis and proliferation of laryngeal carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2020;11(10):864.

116. Lin C, Wu J, Wang Z, Xiang Y. Long non-coding RNA LNC-POTEM-4 promotes HCC progression via the LNC-POTEM-4/miR-149-5p/Wnt4 signaling axis. Cell Signal. 2024;124:111412.

117. Yang D, Li Q, Shang R, Yao L, Wu L, Zhang M, et al. WNT4 secreted by tumor tissues promotes tumor progression in colorectal cancer by activation of the Wnt/beta-catenin signalling pathway. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39(1):251.

118. Asem MS, Buechler S, Wates RB, Miller DL, Stack MS. Wnt5a Signaling in Cancer. Cancers (Basel). 2016;8(9):9919.

119. Xie QY, Zhao GQ, Tang H, Wa QD. Recent advances in understanding the role of Wnt5a in prostate cancer and bone metastasis. Discov Oncol. 2025;16(1):880.

120. Tufail M, Wu C. WNT5A: a double-edged sword in colorectal cancer progression. Mutat Res Rev Mutat Res. 2023;792:108465.

121. Bueno MLP, Saad STO, Roversi FM. WNT5A in tumor development and progression: A comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;155:113599.

122. Feng Y, Ma Z, Pan M, Xu L, Feng J, Zhang Y, et al. WNT5A promotes the metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by activating the HDAC7/SNAIL signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2022;13(5):480.

123. Douglass SM, Fane ME, Sanseviero E, Ecker BL, Kugel CH, 3rd, Behera R, et al. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells Are a Major Source of Wnt5A in the Melanoma Microenvironment and Depend on Wnt5A for Full Suppressive Activity. Cancer Res. 2021;81(3):658–70.

124. Yao L, Zhou C, Liu L, He J, Wang Y, Wang A. Cancer-associated fibroblasts promote growth and dissemination of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma cells by secreting WNT family member 5A. Mol Cell Biochem. 2025 Jun;480(6):3857–72.

125. Rogers S, Zhang C, Anagnostidis V, Liddle C, Fishel ML, Gielen F, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts influence Wnt/PCP signaling in gastric cancer cells by cytoneme-based dissemination of ROR2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2023;120(39):e2217612120.

126. Xu Y, Ren Z, Zeng F, Yang H, Hu C. Cancer-associated fibroblast-derived WNT5A promotes cell proliferation, metastasis, stemness and glycolysis in gastric cancer via regulating HK2. World J Surg Oncol. 2024;22(1):193.

127. Li Y, Wang P, Wu LL, Yan J, Pang XY, Liu SJ. miR-26a-5p Inhibit Gastric Cancer Cell Proliferation and Invasion Through Mediated Wnt5a. Onco Targets Ther. 2020;13:2537–50.

128. Suda K, Okabe A, Matsuo J, Chuang LSH, Li Y, Jangphattananont N, et al. Aberrant Upregulation of RUNX3 Activates Developmental Genes to Drive Metastasis in Gastric Cancer. Cancer Res Commun. 2024;4(2):279–92.

129. Liu Q, Yang C, Wang S, Shi D, Wei C, Song J, et al. Wnt5a-induced M2 polarization of tumor-associated macrophages via IL-10 promotes colorectal cancer progression. Cell Commun Signal. 2020;18(1):51.

130. Liu Q, Song J, Pan Y, Shi D, Yang C, Wang S, et al. Wnt5a/CaMKII/ERK/CCL2 axis is required for tumor-associated macrophages to promote colorectal cancer progression. Int J Biol Sci. 2020;16(6):1023–34.

131. Li X, Qi Q, Li Y, Miao Q, Yin W, Pan J, et al. TCAF2 in Pericytes Promotes Colorectal Cancer Liver Metastasis via Inhibiting Cold-Sensing TRPM8 Channel. Adv Sci (Weinh). 2023;10(30):e2302717.

132. Luo J, Liu L, Shen J, Zhou N, Feng Y, Zhang N, et al. miR?576?5p promotes epithelial?to?mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer by targeting the Wnt5a?mediated Wnt/beta?catenin signaling pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2021;23(2):94.

133. Hirashima T, Karasawa H, Aizawa T, Suzuki T, Yamamura A, Suzuki H, et al. Wnt5a in cancer-associated fibroblasts promotes colorectal cancer progression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;568:37–42.

134. Czikora A, Erdelyi K, Ditroi T, Szanto N, Juranyi EP, Szanyi S, et al. Cystathionine beta-synthase overexpression drives metastatic dissemination in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma via inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation of cancer cells. Redox Biol. 2022;57:102505.

135. Sun X, Chu H, Lei K, Ci Y, Lu H, Wang J, et al. GPR120 promotes metastasis but inhibits tumor growth in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Pancreatology. 2022;22(6):749–59.

136. Wang Y, Hong J, Ge S, Wang T, Mei Z, He M, et al. 9-O-monoethyl succinate berberine effectively blocks the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by targeting Wnt5a protein in inhibiting osteosarcoma growth. Phytomedicine. 2024;132:155430.

137. Wan J, Liu Y, Long F, Tian J, Zhang C. circPVT1 promotes osteosarcoma glycolysis and metastasis by sponging miR-423-5p to activate Wnt5a/Ror2 signaling. Cancer Sci. 2021;112(5):1707–22.

138. Guo H, Su R, Lu X, Zhang H, Wei X, Xu X. ZIP4 inhibits Ephrin-B1 ubiquitination, activating Wnt5A/JNK/ZEB1 to promote liver cancer metastasis. Genes Dis. 2024;11(6):101312.

139. Wu Z, Chen S, Zuo T, Fu J, Gong J, Liu D, et al. miR-139-3p/Wnt5A Axis Inhibits Metastasis in Hepatoblastoma. Mol Biotechnol. 2023;65(12):2030–7.

140. Khan W, Haragannavar VC, Rao RS, Prasad K, Sowmya SV, Augustine D, et al. P-Cadherin and WNT5A expression in assessment of lymph node metastasis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Oral Investig. 2022;26(1):259–73.

141. Zheng H, Chen C, Luo Y, Yu M, He W, An M, et al. Tumor-derived exosomal BCYRN1 activates WNT5A/VEGF-C/VEGFR3 feedforward loop to drive lymphatic metastasis of bladder cancer. Clin Transl Med. 2021;11(7):e497.

142. Cong W, Sun J, Hao Z, Gong M, Liu J. PLOD1 promote proliferation and migration with glycolysis via the Wnt/beta-catenin pathway in THCA. Genomics. 2024;116(6):110943.

143. Zhou Q, Feng J, Yin S, Ma S, Wang J, Yi H. LncRNA FAM230B promotes the metastasis of papillary thyroid cancer by sponging the miR-378a-3p/WNT5A axis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2021;546:83–9.

144. Guan X, Liang J, Xiang Y, Li T, Zhong X. BARX1 repressed FOXF1 expression and activated Wnt/beta-catenin signaling pathway to drive lung adenocarcinoma. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;261(Pt 2):129717.

145. Li H, Tong F, Meng R, Peng L, Wang J, Zhang R, et al. E2F1-mediated repression of WNT5A expression promotes brain metastasis dependent on the ERK1/2 pathway in EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(6):2877–91.

146. Chuang WY, Lee CW, Fan WL, Liu TT, Lin ZH, Wang KC, et al. Wnt-5a-Receptor Tyrosine Kinase-Like Orphan Receptor 2 Signaling Provokes Metastatic Colonization and Angiogenesis in Renal Cell Carcinoma, and Prunetin Supresses the Axis Activation. Am J Pathol. 2024;194(10):1967–85.

147. Li Z, Chen C, Yong H, Jiang L, Wang P, Meng S, et al. PRMT2 promotes RCC tumorigenesis and metastasis via enhancing WNT5A transcriptional expression. Cell Death Dis. 2023;14(5):322.

148. Zhou Q, Liu ZZ, Wu H, Kuang WL. LncRNA H19 Promotes Cell Proliferation, Migration, and Angiogenesis of Glioma by Regulating Wnt5a/beta-Catenin Pathway via Targeting miR-342. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2022;42(4):1065–77.

149. Wilkinson EJ, Raspin K, Malley RC, Donovan S, Nott LM, Holloway AF, et al. WNT5A is a putative epi-driver of prostate cancer metastasis to the bone. Cancer Med. 2024;13(16):e70122.

150. Kim S, You D, Jeong Y, Yoon SY, Kim SA, Kim SW, et al. WNT5A augments cell invasiveness by inducing CXCL8 in HER2-positive breast cancer cells. Cytokine. 2020;135:155213.

151. Al-Zubaidi Y, Chen Y, Khalilur Rahman M, Umashankar B, Choucair H, Bourget K, et al. PTU, a novel ureido-fatty acid, inhibits MDA-MB-231 cell invasion and dissemination by modulating Wnt5a secretion and cytoskeletal signaling. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;192:114726.

152. Yuan Y, Geng B, Xu X, Zhao H, Bai J, Dou Z, et al. Dual VEGF/PDGF knockdown suppresses vasculogenic mimicry formation in choroidal melanoma cells via the Wnt5a/beta-catenin/AKT signaling pathway. Acta Histochem. 2022;124(1):151842.

153. Luo C, Balsa E, Perry EA, Liang J, Tavares CD, Vazquez F, et al. H3K27me3-mediated PGC1alpha gene silencing promotes melanoma invasion through WNT5A and YAP. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(2):853–62.

154. Mohapatra P, Yadav V, Toftdahl M, Andersson T. WNT5A-Induced Activation of the Protein Kinase C Substrate MARCKS Is Required for Melanoma Cell Invasion. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(2):346.

155. Grither WR, Baker B, Morikis VA, Ilagan MXG, Fuh KC, Longmore GD. ROR2/Wnt5a Signaling Regulates Directional Cell Migration and Early Tumor Cell Invasion in Ovarian Cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2024;22(5):495–507.

156. Wei H, Wang N, Zhang Y, Wang S, Pang X, Zhang S. Wnt-11 overexpression promoting the invasion of cervical cancer cells. Tumour Biol. 2016;37(9):11789–98.

157. Wei H, Wang N, Zhang Y, Wang S, Pang X, Zhang J, et al. Clinical significance of Wnt-11 and squamous cell carcinoma antigen expression in cervical cancer. Med Oncol. 2014;31(5):933.

158. Dart DA, Arisan DE, Owen S, Hao C, Jiang WG, Uysal-Onganer P. Wnt-11 Expression Promotes Invasiveness and Correlates with Survival in Human Pancreatic Ductal Adeno Carcinoma. Genes (Basel). 2019;10(11):921.

159. Arisan ED, Rencuzogullari O, Keskin B, Grant GH, Uysal-Onganer P. Inhibition on JNK Mimics Silencing of Wnt-11 Mediated Cellular Response in Androgen-Independent Prostate Cancer Cells. Biology (Basel). 2020;9(7):142.

160. Uysal-Onganer P, Kawano Y, Caro M, Walker MM, Diez S, Darrington RS, et al. Wnt-11 promotes neuroendocrine-like differentiation, survival and migration of prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:55.