Abstract

This literature review examines evidence regarding pathogenesis of endometriosis-associated adenocarcinoma and focuses on the potential role of long, non-coding RNA molecules.

The role of long non-coding RNA species is an area of active research and represents an opportunity for novel biomarker Identification to aid early diagnosis, risk stratification and post-operative disease monitoring.

Keywords

Endometriosis, Ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinoma, Ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma, Long non-coding RNA, Pathogenesis, Carcinogenesis, Atypical endometriosis

Introduction

Ovarian endometriosis is a common medical condition affecting up to 10% of women in the reproductive age group [1] and has an increased lifetime risk of progressing to malignancy [2-4]. There are genetic, immunohistochemical and histopathological features of endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas (EAOCs) to suggest that malignancy occurs through an intermediate non-invasive dysplastic stage called atypical endometriosis [2,5-8]. Literature is emerging about the role of non-coding RNA molecules in the development of both endometriosis [9,10] and also ovarian cancer [11,12]. Many of the articles relating to ovarian cancer pathogenesis and the role of non-coding RNAs discuss ovarian cancer with reference to high-grade serous carcinoma, the most common form of ovarian epithelial malignancy that has the worst prognosis [13]. High-grade serous carcinoma is histologically and biochemically distinct from EAOCs, namely endometrioid and clear cell sub-types of adenocarcinoma [13]. There is a paucity of literature regarding the role of non-coding RNA molecules in the development of EAOC [14]. RNA molecules can be detected and sequenced using massive parallel methods which generates large data sets that require computational analysis for interpretation [15,16]. This review will describe pathogenetic mechanisms of endometriosis, atypical endometriosis with respect to genomics.

Endometriosis

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside of the uterine cavity [17]. Eutopic endometrium refers to glandular epithelium lining the endometrial cavity within the uterus of endometriosis sufferers [17]. Endometriosis often involves the ovary and peritoneum but can be found in deep soft tissues, lymph nodes, and distant sites including breast, lung, urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, umbilicus, inguinal region, pelvic nerves, as well as abdominal scars [18,19]. Endometriosis can therefore be classified as ovarian, superficial peritoneal or deep infiltrating in type [20].

Endometriosis is considered a benign condition by many authors [7,18] but actually shows many of the defining features of malignancy [21,22], for example, the ability to invade and metastasise. Some have suggested that it may be more appropriate, therefore, to reclassify usual-type endometriosis as an indolent form of malignancy with excellent survival rates [21].

Atypical endometriosis is characterised by either cytological or architecturally abnormal features within endometriosis [23]. Architectural abnormalities within atypical endometriosis generally refer to hyperplasia, defined as an increased in the number of cells and or glands in relation to the amount of background supporting connective tissue stroma. [24,25]. Cytological atypia refers to an abnormal cell phenotype characterised by an increased nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, prominent nucleoli and pleomorphism; these are recognised features of dysplasia and are seen in both pre-invasive and invasive malignancies [7,23].

Ovarian carcinomas are subtyped based on histological features, the most common being high-grade serous carcinoma which makes up around 70% of ovarian carcinomas[13,26]. Up to 10% of ovarian carcinomas are endometrioid sub-type, having phenotypic and molecular resemblances to endometroid adenocarcinomas that arise in the endometrial cavity [27,28]. Clear cell carcinoma and endometrioid carcinoma of the ovary are the types most commonly occurring on a background of ovarian endometriosis [29,30] and clear cell carcinoma is equally as common as endometroid type, perhaps reflecting this shared cell of origin. Mucinous carcinoma is less common than endometriosis-related carcinomas at around 3% of ovarian carcinomas [13]. Mucinous carcinoma of the ovary is seen more frequently than this but is often a result of metastases from the gastrointestinal tract and true primary ovarian mucinous carcinoma is rare [31] and thought to arise from Walthard rests, nest of epithelium that occur as embryonic remnants at the junction of distal fallopian tube epithelium continuity with pelvic peritoneal mesothelium [26]. Low-grade serous carcinoma occurs in less than 5% of ovarian carcinoma cases and has a distinct molecular origin from high-grade serous carcinoma and should be regarded as entirely separate entities despite the similarity in their name [13,26,32]. High-grade serous carcinomas develop mutations in TP53 early in pathogenesis within ciliated columnar epithelium lining the fallopian tubes [33,34]. In contrast, low grade serous carcinomas are characterised by mutations in KRAS and BRAF genes and develop in a sequential manner from benign serous cyst adenoma to serous borderline tumour to low grade serous carcinoma when invasion of ovarian stroma occurs [35,36] (Table 1). Other ovarian carcinoma types are even rarer and include carcinosarcoma and Brenner tumours for example [27,37].

|

Characteristic |

High-grade serous [37,39-42] |

Endometrioid [13,29,38,42,43] |

Clear cell [43] |

Mucinous [13,38,42] |

Low-grade serous [36,37,44-46] |

|

Average age at diagnosis |

63 |

56 |

51 |

54 |

47 |

|

Gene mutations |

TP53 BRCA1/2 RAD51C/D BRIP1 MSI genes |

ARID1A, PTEN, CTNNB1, PIK3CA PPP2R1A |

ARID1A PIK3CA PPP2R1A ZNF217 |

KRAS, HER2 ampl. TP53 c-myc |

KRAS NRAS BRAF |

|

Positive IHC |

CK7, ER, WT1, p16, p53, PAX8 |

Vimentin, ER, PR, PAX8 |

CK7, napsinA |

CK7, CK20, cdx2 |

CK7, ER, WT1, PAX8 |

|

FIGO Stage at diagnosis |

51% stage III 29% stage IV |

58-64% stage I |

58-64% stage I |

58-64% stage I |

78% stage I |

|

Platinum-based chemotherapy response |

More than 70% |

60% |

22-56% |

20-60% |

4-40% |

|

Five-year survival |

10-26.9% |

82% |

66% |

71% |

88% |

|

FIGO: International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; IHC: Immunohistochemistry |

|||||

Low grade serous, seromucinous and mucinous carcinomas have also reported in association with endometriosis but rarely [47,48]. For the purposes of this literature review, EAOC will refer to endometrioid and clear cell carcinomas only.

Clinical Features

Endometriosis can cause multiple symptoms including painful periods, cyclical pelvic pain, sometimes irregular or heavy periods, painful intercourse, bowel and bladder pain, female sub-fertility, and chronic fatigue [49,50]. Endometriosis symptoms such as severe dysmenorrhea, inter-menstrual pain, dyspareunia, painful defecation, dysuria, back pain, fatigue, and infertility have a profound negative impact on quality of life. [51] Laparoscopic removal of peritoneal lesions can provide tissue for diagnosis and relief from pain, but three quarters of patients relapse within 2 years of surgery [52-54]. Subfertility is a major cause of psychological morbidity in women with endometriosis [55-58]. Some authors suggest that eutopic endometrium in women with endometriosis is abnormal and the cause of infertility [17,56]. The abnormal state of eutopic endometrium in these women may in part be responsible for the development of endometriosis [20]. Endometriosis of the peritoneum appears as purple/brown blebs just under the peritoneal surface often with inflammatory adhesions at diagnostic laparoscopy. The appearances would be the same for both typical and atypical endometriosis as atypia can only be diagnosed by a histopathologist during microscopic examination of tissue [17,18,59].

Pathogenesis of endometriosis

Even though endometriosis has been recognized for around 150 years [17] there have only recently been advances in the understanding of its molecular pathogenesis [60]. There are several theories of pathogenesis as outlined below:

Retrograde or “reflux” menstruation: Retrograde menstruation has been a longstanding hypothesis of endometriosis [61,62] and is said to occur in most menstruating women [17]. It is postulated that abnormal eutopic endometrium confers a survival advantage for endometrial cells when they reach peritoneum [49,63]. A large number of differentially expressed genes (72 in total; 66 up-regulated and 6 down-regulated) were identified in eutopic endometrium samples from women with endometriosis and the mRNA products identified were associated with angiogenesis, extracellular matrix remodelling, cell proliferation and differentiation [63]. In particular matrix metalloproteinases (MMP) 3,10,11 and 27 were over expressed and these proteins are thought to aid attachment and invasion of retrograde menstrual endometrial cells on the peritoneal and ovarian surface [64,65]. Suda et al. provide genomic evidence in support of this hypothesis by demonstrating an overlap in somatic mutations in eutopic endometrium compared with that in corresponding ovarian endometriomas [66].

Coelomic metaplasia: An alternative theory of pathogenesis of endometriosis is in-situ metaplasia of peritoneal surface serous epithelium (coelomic epithelium). Metaplasia is the transformation from one fully differentiated epithelial type into another [67].

Metastasis: Metastasis of endometrial tissue via lymphatics and blood vessels to sites distant from their origin has long been considered a cause of endometriosis [68]. This pathogenetic mechanism may be restricted to deep, infiltrating types of endometriosis [20]. There is evidence to support this idea as it has been shown that deep infiltrating endometriosis shows different epithelial cell genetic mutations compared with peritoneal endometriosis [22,69-71].

Heredity: There is a 2 to15% risk of developing endometriosis if a first-degree relative is affected [72] and around 50% of women with endometriosis have a family history [73,74]. Genome wide association studies (GWAS) have been carried out to try to delineate which genes may be involved [72,75]. A meta-analysis by Sapkota et al. [74] describes 14 gene loci that have are thought associated with a risk of developing endometriosis. There is a concentration of loci on chromosomes 2, 6 and 7 involving GREB1, ETAA1, FN1 and IL1A on chromosome 2, CCDC170, ID4 and SYNE1 on chromosome 6 and two loci located within intergenic regions on the short arm of chromosome 7; one 99kb upstream of miRNA148a at locus 7p15.2 and the other 290kb upstream of NFEL2L3. These findings are based on high-throughput sequencing from a large cohort of people; 17,045 endometriosis cases and 191,596 controls using robust methods. How these genes determine heritability is a complex question which is, as yet, unanswered.

Environmental factors: High-levels of environmental dioxin, oestrogen and oestrogen-like compounds have been suggested by some as a potential contributor to developing endometriosis, but it is difficult to attribute risks to a single chemical [17,76]. There are also case reports of tamoxifen causing a proliferative, architectural atypia within endometriosis of the ovary [77].

Somatic genetic events in endometriosis, atypical endometriosis and EAOC

Scott was one of the first people to recognize the association between endometriosis and malignancy [78]. The risk of malignant transformation from usual type endometriosis is estimated to be between 0.3% and 2% [2,3]. Atypical features of endometriosis in the absence of a co-existing malignancy is rare and estimated to be present in only 1.7% of cases of ovarian endometriosis [79]. Some authors suggest that severe atypia is a precursor for malignant change [80-82].

The malignant transformation of endometriosis appears to occur on a background of oxidative stress and inflammation induced by cycling endometrial glands that produce reactive oxygen species and free iron from breakdown products of haemoglobin [83-85]. These background features result in clear cell carcinoma which is estrogen receptor negative by immunohistochemistry (IHC) and HNF1beta positive as a result of up regulation of gene expression stimulated by hyperoxia [86,87]. In contrast, endometrioid ovarian adenocarcinomas tend to be ER positive and HNF1beta negative due to background hyper-estrogenism [50,87,88].

HNF1beta has also been shown to be upregulated by nuclear positivity by IHC and to have a hypomethylated gene promotor in clear cell renal cell carcinomas [89]. Integrative bioinformatics links HNF1B with clear cell carcinoma and tumor-associated thrombosis. Both renal and gynaecological origin clear cell carcinomas clinically show a tendency towards thrombosis and an explanation for this observation may lie in the finding that HNF1B transcriptional targets include molecules that govern the blood clotting pathways [90]. Developments in this area may lead to tumor agnostic oncological therapies in the future [91].

Table 2 summarizes this data from a total of 987 samples in comparative form between these diagnostic groups as a percentage of the number of samples tested. No data is recorded for endometriosis in this cancer database due to its current classification as a benign entity. The COSMIC database also describes the type of mutation most commonly seen in EAOC as separate groups, clear cell and endometrioid–type adenocarcinoma. Missense mutations are by far the most common type of somatic mutation as can be seen in Table 3. The Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) database records point mutations in somatic genes of ovarian neoplasms associated with endometriosis (histological type not otherwise specified, from ovarian clear cell carcinomas and ovarian endometrioid carcinoma [92].

|

Gene |

Ovarian EAOC, not otherwise specified |

Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma |

Ovarian Endometrioid carcinoma |

|

PIK3CA |

21 |

33 |

23 |

|

ARID1A |

50 |

50 |

25 |

|

TERT |

0 |

17 |

0 |

|

KRAS |

4 |

8 |

14 |

|

PPP2R1A |

0 |

8 |

6 |

|

TP53 |

0 |

11 |

51 |

|

CKDN2A |

0 |

6 |

8 |

|

CTNNB1 |

34 |

3 |

27 |

|

PTEN |

31 |

4 |

18 |

|

FBXW7 |

0 |

6 |

7 |

|

BRAF |

0 |

1 |

3 |

|

SMARCA4 |

0 |

10 |

0 |

|

BRCA2 |

0 |

9 |

11 |

|

KEAP1 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

|

SPOP |

0 |

12 |

10 |

|

NRAS |

0 |

3 |

0.047 |

|

FGFR2 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

|

ATM |

0 |

3 |

0.026 |

|

KDM5C |

0 |

6 |

0 |

|

ARID1B |

0 |

9 |

0 |

|

POLE |

0 |

0.02 |

18 |

|

APC |

0 |

0 |

9 |

|

BRCA1 |

0 |

0 |

8 |

|

ATR |

0 |

0.27 |

26 |

|

BRIP1 |

0 |

0. |

29 |

|

PIK3R1 |

0 |

0.029 |

11 |

|

FGFR2 |

0 |

0.033 |

3 |

|

ERBB2 |

0 |

0.031 |

3 |

|

CTCF |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

CARD11 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

Total samples tested |

62 |

491 |

434 |

|

Mutation Type |

Clear Cell Carcinoma: Number |

Clear Cell Carcinoma: Percentage |

Endometrioid Carcinoma: Number |

Endometrioid Carcinoma: Percentage |

|

Nonsense |

57 |

11.61 |

33 |

7.60 |

|

Missense |

336 |

68.43 |

358 |

82.49 |

|

Synonymous |

1 |

0.2 |

22 |

5.07 |

|

In-frame insertion |

4 |

0.81 |

1 |

0.23 |

|

Frame-shift insertion |

34 |

6.92 |

10 |

2.30 |

|

In-frame deletion |

4 |

0.81 |

6 |

1.38 |

|

Frame-shift deletion |

59 |

12.02 |

26 |

5.99 |

|

Complex |

3 |

0.61 |

1 |

0.23 |

|

Other |

15 |

3.05 |

17 |

3.92 |

|

Total |

491 |

100 |

434 |

100 |

One can see from the data that the overall majority of mutations for both types of cancer are missense, which means a single nucleotide change resulting in a different codon that incorporates an alternative amino acid into the protein sequence. COSMIC also records the presence of copy number variation, gains and losses, for approximately 150 other genes in clear cell carcinoma and around 60 genes in endometrioid carcinoma.

Copy number variants have also been described in endometriosis alone and are said to contribute to its development [93]. This includes gains in sub-telomeric regions of chromosomes 1p, 16p, 19p, and 20p and losses in 17q and 20q [93]. The inter-genic locus 19q13.1 was also noted to have a particular association with endometriosis in this study [93].

One of the most common and well-studied somatic gene mutations in clear cell and endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the ovary is in the ARID1A (AT-rich interaction domain containing protein 1A) gene [94]. Authors suggest that this gene acts as a tumor suppressor in normal cells and mutation results in malignant transformation as an early event in the process [95-98]. ARID1A is mutated in 42-61% of clear cell carcinomas and 21-33% of endometrioid carcinomas [20]. The normal protein product of ARID1A, BAF250a, forms part of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex [99] and may therefore have interactions with non-coding RNAs as part of normal cell transcription control mechanisms. ARID1A has been shown to interact with the long non-coding RNA molecule MVIH and alterations of this interaction as a result of ARID1A gene mutations have been implicated in the pathogenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma [100]. HOTAIR is another lncRNA molecule that has been shown to interact with chromatin remodeling complex proteins such as BAF250a in cancers that metastasize [101,102] and this pathway has recently been shown to have potential for developing new treatments in renal cell carcinoma [103]. The most common form of renal cell carcinoma has a clear cell phenotype similar to that of clear cell carcinoma of the ovary. It may be that similar molecular events in these cancers yield a similar phenotype. The COSMIC database of mutations illustrates that the majority of mutations in the ARID1A gene are nonsense type and therefore likely result in a truncated for of protein if its corresponding messenger RNA is translated (https://cancer.sanger.ac.uk). This process results in loss of expression of the BAF250a protein, which can be detected by immunohistochemistry in tissue sections in normal tissues [104]. Some authors suggest loss of this protein in atypical endometriosis without neoplasia is a useful indicator of high risk to progression to cancer [104,105]. However, there is no clear evidence to date that BAF250a can predict prognosis in EAOC or highlight treatment options [94,106].

Another frequent mutation in ovarian clear cell carcinoma arises in TERT (Telomerase reverse transcriptase) and confers a poor prognosis when present [107,108]. A study of 525 gynecological cancers showed that longer telomeres were a particular feature of clear cell carcinoma and that this mutation tended to be mutually exclusive with loss of ARID1A protein expression [109]. This is of particular relevance as non-coding RNA is involved in the regulation of telomerase [110] and the Telomerase RNA Component (TERC) gene is overexpressed in several human cancers [111-113].

PIKC3A (Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, catalytic, alpha) somatic gene mutations are more common than TERT in both clear cell and endometrioid types of ovarian adenocarcinoma. PIKC3A mutations have been shown to be an early event in the neoplastic transformation of endometriosis of the most common genes to be mutated in both clear cell and endometrioid types [114,115]. PIKC3A mutations are often seen in conjunction with CTNNB1 (Catenin, beta1) mutations [116] but CTNNB1 mutations are much more common in endometrioid type ovarian carcinoma than clear cell carcinomas. Both these mutations have also been found together in cells of atypical endometriosis in a context of synchronous carcinoma [117]. Mutations in CTNNB1 are also frequently seen in endometrioid carcinoma of the uterine cavity and catenin mutations are seen at around the same rate [118]. Microsatellite instability and PTEN mutations are seen less frequently in endometrioid ovarian EAOC than compared with endometrial primaries [118] but given there are some overlaps between the somatic genetic mutations in ovarian and endometrial endometrioid-type adenocarcinomas it is likely that there are also overlaps in the genetic expression profile, otherwise known as transcriptomics.

Transcriptomics

An expression microarray study of eutopic endometrium from patients with endometriosis found potential candidate genes that predispose to developing endometriosis included FOXO1A, MIG6 and CYP26A1 [119].

There are differences with respect to carcinogenesis. However, Fridley et al. found that 32 protein-coding genes were expressed in a mixed group of endometrioid and clear cell carcinomas of the ovary and these included MAP2K6, KIAA1324, CDH1, ENTPD5, LAMB1, and DRAM1 [120]. Tassi et al. have shown that FOXM1 expression is associated with a worse prognosis in non-serous types of ovarian cancer [121]. Clear cell and endometrioid types of ovarian malignancy are said to have an expression profile similar to that of normal endometrium according to findings of microarray studies [122]. The expression profiles appear different between clear cell and endometroid adenocarcinoma groups when compared with normal surface ovarian epithelial cells. It has been found that the greatest difference in gene expression in endometrioid carcinomas lies between SERPINA1, MT1G, and CXCL14 genes compared with clear cell carcinoma where there are differences in PROM1 ABP1 and RBP4 [122]. It is interesting to note there is no overlap between the genes expressed in these EAOC tumours and those listed as somatically mutated genes in the COSMIC database; it may be that functional expression of RNA and protein is more important in pathogenesis of EAOC than the mere presence of a somatic gene mutation which is not transcriptionally active.

Non-coding RNA

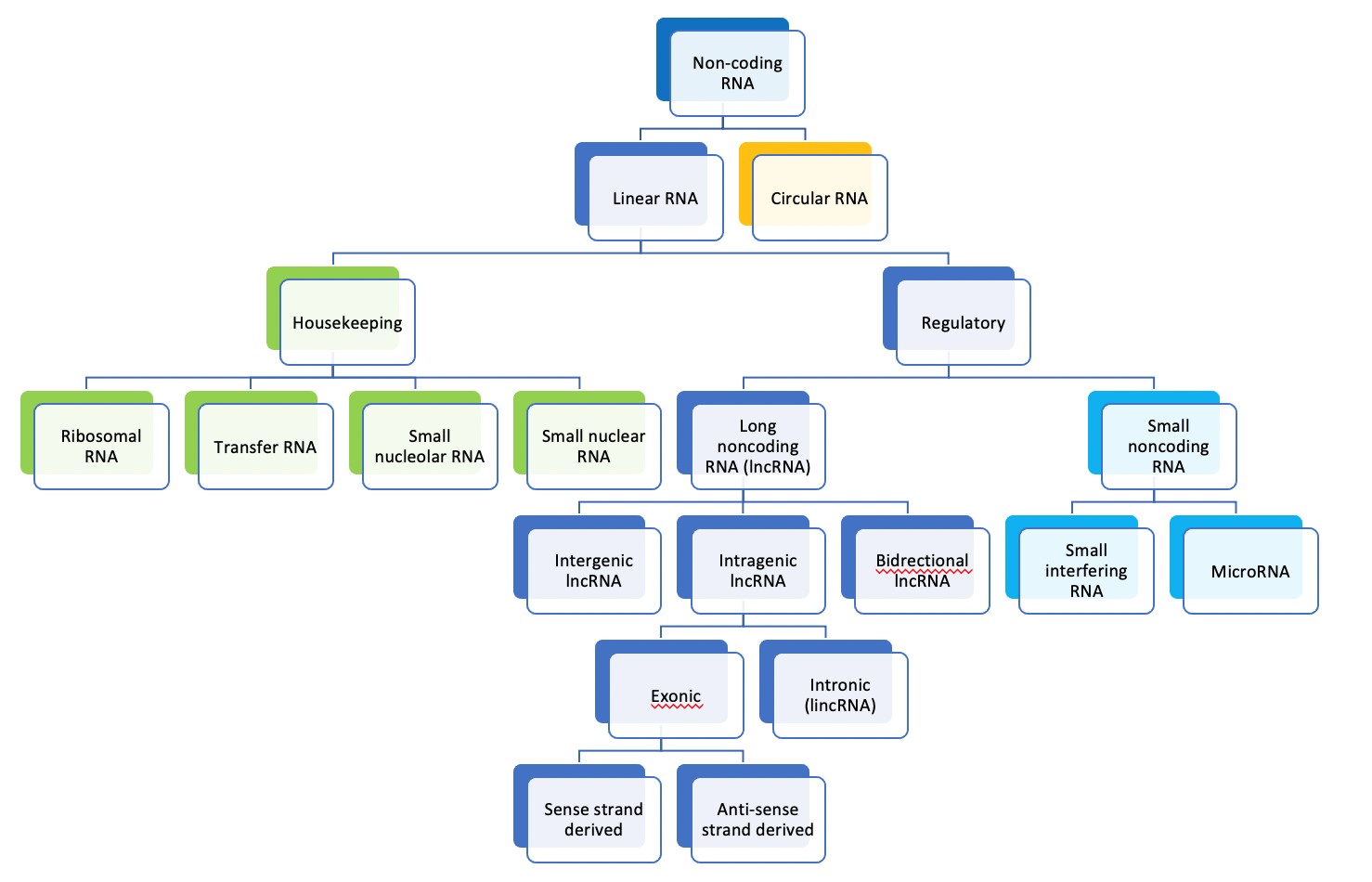

Non-coding RNA is transcribed from DNA but does not encode protein and accounts for around 70% of the human genome [123-125]. Many thousands of non-coding RNA molecules are known, and they take different forms [126,127]. They can be classified according to where in the genome they are coded and by the size and shape of the molecules, as seen in diagram 1 [10]. Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are more than 200 nucleotides long and linear according to this scheme [10].

The function of LncRNAs is diverse and predominantly regulatory in nature [16]. They are involved in epigenetics and interact with polycomb repressive proteins to acetylate or methylate histone proteins in chromatin to regulate DNA activation or repression [128,129]. They are also involved in imprinting, for example the lncRNA molecule XIST is responsible for suppression of transcription of one of the X-chromosomes in female humans [130,131].

LncRNA molecules are key regulators of pre- and post-transcriptional control of gene expression [16]. In pre-transcriptional control they can act in cis by regulating transcription factors adjacent to or overlapping their site of coding and, due to both their length and ability to form 2- and 3-dimensional structures, they can act in trans to regulate transcription factors at sites distant to their location [16,132,133]. They can also regulate mRNA splicing within the nucleus [134]. In post-transcriptional control of gene expression, lncRNAs can interact with microRNA molecules that target messenger RNA for degradation before translation into protein [132].

Long non-coding RNAs are known to have oncogenic and tumour suppressor activity in a variety of human cancers [132,135,136]. Hanahan and Weinberg described six key defining features of malignancy and lncRNA molecules have been found to be involved in cell pathways for all these features; they include sustaining proliferative signalling, evading growth suppressors, enabling replicative immortality, activating invasion and metastasis, inducing angiogenesis and resisting cell death [132,137]. These findings are summarized in Table 4.

Figure 1. Classification of RNA molecules according to size and cellular function [10].

|

Cancer Hallmark |

LncRNA |

Mode of Action |

|

Sustaining proliferative signalling |

SRA PCAT-1 RN7SK KRASP1 |

Transcriptional co-activator Regulates gene expression Regulated transcription miRNA sponge |

|

Evading growth suppressors |

ANRIL GAS5 lincRNA-p21 E2F4 antisense |

Chromatin remodelling Competitor Transcriptional co-repressor Regulates gene expression |

|

Enabling replicative immortality |

TERC TERRA |

RNA primer Enzymatic inhibitor |

|

Activating invasion and metastasis |

MALAT1 HOTAIR HULC BC200 |

Modulates protein activity Chromatin remodelling miRNA sponge Translational modulator |

|

Inducing angiogenesis |

AlphaHIF sONE tie-1AS ncR-uPAR |

RNA decay RNA decay RNA decay Regulates gene expression |

|

Resisting cell death |

PCGEM1 SPRY4-IT1 PANDA LUST |

Regulates gene expression Unknown Modulates protein activity RNA-splicing |

Long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) in endometriosis, atypical endometriosis and endometriosis-associated ovarian cancers

Endometriosis: There is emerging evidence regarding non-coding RNA expression in endometriosis [9,10,138,139]. Cui et al. looked at the profile of messengers RNA transcripts and non-coding RNA sequences present in the endometrial biopsies from women with and without endometriosis. They describe a large data set and show impact on a number of cell signaling pathways involved in angiogenesis, proliferation, invasion, adhesion and migration. They discovered eighty-six lncRNAs in their data set, 22 of which were considered novel. The SNORD3A (a type of small nucleolar RNA involved in resistance to oxidative stress [140] was the most up-regulated and ABO was the most down-regulated of the known RNA molecules found in comparison with controls [9]. TCONS_00006582 and TCONs_08347373 were novel transcripts of unknown function or relevance [9]. This study is of questionable reliability given that ABO is a protein-coding gene and the authors have included a snoRNA under the lncRNA classification.

Atypical endometriosis: There are no published studies regarding the lncRNA profiles found in epithelial cells of atypical endometriosis to date. This perhaps reflects the rarity of isolated atypical endometriosis of the ovary.

Endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer: LncRNA molecules play a role in ovarian carcinogenesis by affecting a number of cell signalling pathways from cellular proliferation, apoptosis and control of the cell cycle to conferring drug resistance and propagating neoplasm to invade and metastasize [9,12,16,141]. There are no papers that describe the influence of lncRNA specifically regarding carcinogenesis of EAOC but there is evidence regarding the role of microRNAs (miRNAs) [142] and circulating blood miRNA molecules have been targeted by researchers as potential diagnostic biomarkers for endometriosis as compared with a surgical tissue biopsy [143-146]. Given that lncRNAs interact with cytoplasmic miRNA in post-transcriptional control of mRNA translation, it may be that lncRNAs also play a significant role in pathogenesis of EAOC and represent potential as biomarkers for diagnosis.

There is overlap in expression profiling seen between clear cell and endometrioid carcinomas and that seen in normal endometrium and this may be reflected in lncRNA activity also [122]. We know that NEAT1 is overexpressed in endometrial endometroid adenocarcinoma and is thought to be a critical step in pathogenesis of this malignancy [147]. MALAT1, HOTAIR, OVAL, and H19 lncRNAs are also overexpressed in endometrioid carcinoma of the endometrium [148].

MALAT1 promotes development of endometrioid carcinoma via regulation of the wnt/beta-catenin signalling pathway [149,150]. MALAT1 has also been implicated in regulation of cellular apoptosis in ‘ovarian cancer’ via influence on the PI3K/AKT cell signaling pathway [151]. MALAT1 may also affect functioning of microRNA molecules miR-211 and miRNA-506 resulting in tumorigenesis in the ovary according to some studies [152-155].

HOTAIR, otherwise known as homeobox transcript antisense intergenic RNA, has been found to be up-regulated in endometrial carcinoma using in-situ hybridization methods specific to this lncRNA [14]. HOTAIR is transcribed from intergenic regions of the cluster of Homeobox genes which are usually only expressed in embryonic development as they are responsible for overall organizational development of living organisms [156].

He et al. suggests that overexpression of HOTAIR is correlated with a poorer clinical outcome in this cancer type, but their experimental sample contained a mixture of serous and endometrioid types of endometrial cancer and therefore calls the significance of the study findings into question [14]. HOTAIR has also been found to be transcriptionally up-regulated in response to increased estrogen levels which may have implications for endometriosis sufferers [157,158].

OVAAL (ovarian adenocarcinoma amplified lncRNA) is found on chromosome 1 at locus 1q25 and has been shown to over-expressed in endometrioid and serous carcinomas of the ovary [159,160]. Its function within ovarian carcinoma cells is not yet known [148].

H19 is an imprinted gene expressed from maternally inherited chromosomes and yields a well-researched lncRNA molecule in humans [161,162]. H19 is only expressed in embryonic tissues under normal physiological conditions but is found to be overexpressed 85% of ovarian cancers and some benign uterine neoplasms [163-165]. It is associated with the ability of neoplasms to metastasize [163,166]. H19 is on chromosome 11 and codes for a MAP kinase protein as well as miRNA 675 and a lncRNA molecule involved in cyclicity of endometrial mucosa [167,168]. H19 has been shown to be involved in regulation of steroid hormone synthesis [169] and this may be why it has been implicated in the pathogenesis of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrioid carcinoma [170]. H19 levels have also been found to be inversely proportional to the degree of endometrioid adenocarcinoma differentiation and so, by inference, correlates with prognosis and survival [170,171]. Other studies suggest that H19 promotes ovarian malignancy by interacting with cell signaling pathways promoting cell proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis [172,173]. Interestingly, there have been recent phase 1 dose-toxicity trials aimed at treatments directed at H19 in patients with platinum resistant tubo-ovarian high-grade serous carcinoma [174].

There are many other lncRNA molecules that have been implicated as being involved in ovarian carcinoma pathogenesis and these include SOX2OT, DGCR5, PC3A, FAL1, ABO73614, HULC, ZFAS1, HST2, LSINCT5, PVT1, TUG1, ANRIL, PVT1, HOST2, GAS5, PTAF, LINK-A, HOXA11-AS, BC200, many of which are said to act as oncogenes [146,148,175-177]. Most of these studies refer to ovarian cancer as though it were a homogenous single entity. If a mixed collection of histological types of ovarian carcinoma were used this would generate unreliable results as discussed above [178]. Having a collection of pure tissue samples for sequencing is perhaps even more important in the context of lncRNA as these molecules are thought to be pivotal in determining cell differentiation [16,179]. Any study resulting from this literature review will use accurate histopathological classification of ovarian carcinoma to generate a robust data set regarding the presence of non-coding RNA molecules.

Conclusion

Long non-coding RNA molecules are involved in carcinogenesis through interactive networks alongside messenger RNA and microRNAs. We are just beginning to piece together the complex pathways that exist governing protein expression and it is clear that non-coding elements o the human genome are most definitely not ‘junk’ [131]. There is evidence that H19, MALAT1, OVAAL, HOTAIR, and possibly NEAT1, may be involved in the pathogenesis of EAOCs but, to date, much of the work has justifiably focussed on high-grade serous carcinoma due to its common occurrence [11,37,180]. There is a need to clarify the relevance of lncRNA molecule sin EAOCs, and particularly in ovarian clear cell carcinomas because of the frequency of resistance to standard platinum-based chemotherapy with consequent poor prognosis [38,181].

Future Directions

LncRNA molecules represent potential biomarkers for early diagnosis of EAOC by less invasive methods than surgery [142] and could also be used as a starting point for discovery of novel oncological drugs [182].

It remains to be seen what spatial resolution may bring to the understanding of EAOC pathology as both for protein coding gene expression and for the non-coding genome. LncRNAs are not well studied by this method but reasons for employing this technique To EAOC pathology are clear; spatial transcriptomics will allow focus on the epithelial cells forming atypical endometriosis, in the background of EAOCs and also in standalone cases, where the number of cells of interest are few [183,184]. Digital spatial profiling (DSP) holds great promise for enhanced reproducibility within the field of cancer research [184]. DSP will allow for detailed exploration of tumoral heterogeneity and focused correlation with phenotype, the cornerstone of clinical interpretation of genetics, somatic and constitutional [185-187]. Better understanding of the pathogenesis of EAOC may help inform development of lncRNAs by immunohistochemistry may open up a new angle on research in this domain and create opportunities for translation to clinical diagnostic practice as a form of companion diagnostic test that is rapid and cost effective for the NHS to administer [14,188].

References

2. Sainz de la Cuesta R, Eichhorn JH, Rice LW, Fuller AF, Jr., Nikrui N, Goff BA. Histologic transformation of benign endometriosis to early epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;60(2):238-44.

3. Wei JJ, William J, Bulun S. Endometriosis and ovarian cancer: a review of clinical, pathologic, and molecular aspects. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2011;30(6):553-68.

4. Wilbur MA, Shih IM, Segars JH, Fader AN. Cancer Implications for Patients with Endometriosis. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35(1):110-6.

5. Jiang X, Morland SJ, Hitchcock A, Thomas EJ, Campbell IG. Allelotyping of endometriosis with adjacent ovarian carcinoma reveals evidence of a common lineage. Cancer Res. 1998;58(8):1707-12.

6. Eurich KE, Goff BA, Urban RR. Two cases of extragonadal malignant transformation of endometriosis after TAH/BSO for benign indications. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2019;28:23-5.

7. Kajiyama H, Suzuki S, Yoshihara M, Tamauchi S, Yoshikawa N, Niimi K, et al. Endometriosis and cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 2019;133:186-92.

8. Dentillo DB, Meola J, Ferriani RA, Rosa-E-Silva JC. Common Dysregulated Genes in Endometriosis and Malignancies. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2016;38(5):253-62.

9. Cui D, Ma J, Liu Y, Lin K, Jiang X, Qu Y, et al. Analysis of long non-coding RNA expression profiles using RNA sequencing in ovarian endometriosis. Gene. 2018;673:140-8.

10. Ferlita A, Battaglia R, Andronico F, Caruso S, Cianci A, Purrello M, et al. Non-Coding RNAs in Endometrial Physiopathology. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(7).

11. Fu Y, Biglia N, Wang Z, Shen Y, Risch HA, Lu L, et al. Long non-coding RNAs, ASAP1-IT1, FAM215A, and LINC00472, in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143(3):642-9.

12. Wang JY, Lu AQ, Chen LJ. LncRNAs in ovarian cancer. Clin Chim Acta. 2019;490:17-27.

13. Prat J, D'Angelo E, Espinosa I. Ovarian carcinomas: at least five different diseases with distinct histological features and molecular genetics. Hum Pathol. 2018;80:11-27.

14. He X, Bao W, Li X, Chen Z, Che Q, Wang H, et al. The long non-coding RNA HOTAIR is upregulated in endometrial carcinoma and correlates with poor prognosis. Int J Mol Med. 2014;33(2):325-32.

15. Elliott Da, Ladomery Ma. Molecular biology of RNA. Second edition. ed.

16. Fatica A, Bozzoni I. Long non-coding RNAs: new players in cell differentiation and development. Nat Rev Genet. 2014;15(1):7-21.

17. Giudice LC, Kao LC. Endometriosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1789-99.

18. Bulun SE. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(3):268-79.

19. Machairiotis N, Stylianaki A, Dryllis G, Zarogoulidis P, Kouroutou P, Tsiamis N, et al. Extrapelvic endometriosis: a rare entity or an under diagnosed condition? Diagn Pathol. 2013;8:194.

20. Dawson A, Fernandez ML, Anglesio M, Yong PJ, Carey MS. Endometriosis and endometriosis-associated cancers: new insights into the molecular mechanisms of ovarian cancer development. Ecancermedicalscience. 2018;12:803.

21. Bouquet de Joliniere J, Major A, Ayoubi JM, Cabry R, Khomsi F, Lesec G, et al. It Is Necessary to Purpose an Add-on to the American Classification of Endometriosis? This Disease Can Be Compared to a Malignant Proliferation While Remaining Benign in Most Cases. EndoGram® Is a New Profile Witness of Its Evolutionary Potential. Front Surg. 2019;6:27.

22. Anglesio MS, Papadopoulos N, Ayhan A, Nazeran TM, Noë M, Horlings HM, et al. Cancer-Associated Mutations in Endometriosis without Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(19):1835-48.

23. LaGrenade A, Silverberg SG. Ovarian tumors associated with atypical endometriosis. Hum Pathol. 1988;19(9):1080-4.

24. Parker RL, Dadmanesh F, Young RH, Clement PB. Polypoid endometriosis: a clinicopathologic analysis of 24 cases and a review of the literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(3):285-97.

25. Jaegle WT, Barnett JC, Stralka BR, Chappell NP. Polypoid endometriosis mimicking invasive cancer in an obese, postmenopausal tamoxifen user. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017;22:105-7.

26. McCluggage WG. Morphological subtypes of ovarian carcinoma: a review with emphasis on new developments and pathogenesis. Pathology. 2011;43(5):420-32.

27. Kaku T, Ogawa S, Kawano Y, Ohishi Y, Kobayashi H, Hirakawa T, et al. Histological classification of ovarian cancer. Med Electron Microsc. 2003;36(1):9-17.

28. Wu RC, Veras E, Lin J, Gerry E, Bahadirli-Talbott A, Baras A, et al. Elucidating the pathogenesis of synchronous and metachronous tumors in a woman with endometrioid carcinomas using a whole-exome sequencing approach. Cold Spring Harb Mol Case Stud. 2017;3(6).

29. McCluggage WG. Endometriosis-related pathology: a discussion of selected uncommon benign, premalignant and malignant lesions. Histopathology. 2020;76(1):76-92.

30. Wang Y, Mang M, Wang L, Klein R, Kong B, Zheng W. Tubal origin of ovarian endometriosis and clear cell and endometrioid carcinoma. Am J Cancer Res. 2015;5(3):869-79.

31. Casey L, Singh N. Metastases to the ovary arising from endometrial, cervical and fallopian tube cancer: recent advances. Histopathology. 2020;76(1):37-51.

32. Muinao T, Pal M, Deka Boruah HP. Origins based clinical and molecular complexities of epithelial ovarian cancer. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules. 2018;118(Pt A):1326-45.

33. Labidi-Galy SI, Papp E, Hallberg D, Niknafs N, Adleff V, Noe M, et al. High grade serous ovarian carcinomas originate in the fallopian tube. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1093.

34. Meinhold-Heerlein I, Fotopoulou C, Harter P, Kurzeder C, Mustea A, Wimberger P, et al. The new WHO classification of ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancer and its clinical implications. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293(4):695-700.

35. Seidman JD, Savage J, Krishnan J, Vang R, Kurman RJ. Intratumoral Heterogeneity Accounts for Apparent Progression of Noninvasive Serous Tumors to Invasive Low-grade Serous Carcinoma: A Study of 30 Low-grade Serous Tumors of the Ovary in 18 Patients With Peritoneal Carcinomatosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2020;39(1):43-54.

36. Kaldawy A, Segev Y, Lavie O, Auslender R, Sopik V, Narod SA. Low-grade serous ovarian cancer: A review. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143(2):433-8.

37. Tavassoli FA, Devilee P. Pathology and genetics of tumours of the breast and female genital organs. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer ; Oxford : Oxford University Press [distributor]; 2003.

38. Chávarri-Guerra Y, González-Ochoa E, De-la-Mora-Molina H, Soto-Perez-de-Celis E. Systemic therapy for non-serous ovarian carcinoma. Chin Clin Oncol. 2020.

39. Taylor A, Brady AF, Frayling IM, Hanson H, Tischkowitz M, Turnbull C, et al. Consensus for genes to be included on cancer panel tests offered by UK genetics services: guidelines of the UK Cancer Genetics Group. J Med Genet. 2018;55(6):372-7.

40. Singh N, McCluggage WG, Gilks CB. High-grade serous carcinoma of tubo-ovarian origin: recent developments. Histopathology. 2017;71(3):339-56.

41. UK CR. Ovarian Cancer Survival Statistics by Stage [Internet]. 2019.

42. Torre LA, Trabert B, DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Samimi G, Runowicz CD, et al. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(4):284-96.

43. Kobayashi H. Malignant transformation of endometriosis. First ed. Harada T, editor. Tokyo: Springer; 2014.

44. Schmeler KM, Sun CC, Bodurka DC, Deavers MT, Malpica A, Coleman RL, et al. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for low-grade serous carcinoma of the ovary or peritoneum. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;108(3):510-4.

45. Dalton HJ, Fleming ND, Sun CC, Bhosale P, Schmeler KM, Gershenson DM. Activity of bevacizumab-containing regimens in recurrent low-grade serous ovarian or peritoneal cancer: A single institution experience. Gynecol Oncol. 2017;145(1):37-40.

46. Slomovitz B, Gourley C, Carey MS, Malpica A, Shih IM, Huntsman D, et al. Low-grade serous ovarian cancer: State of the science. Gynecol Oncol. 2020;156(3):715-25.

47. Rodriguez IM, Irving JA, Prat J. Endocervical-like mucinous borderline tumors of the ovary: a clinicopathologic analysis of 31 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004;28(10):1311-8.

48. Rambau PF, McIntyre JB, Taylor J, Lee S, Ogilvie T, Sienko A, et al. Morphologic Reproducibility, Genotyping, and Immunohistochemical Profiling Do Not Support a Category of Seromucinous Carcinoma of the Ovary. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017;41(5):685-95.

49. Laganà AS, La Rosa VL, Rapisarda AMC, Valenti G, Sapia F, Chiofalo B, et al. Anxiety and depression in patients with endometriosis: impact and management challenges. Int J Womens Health. 2017;9:323-30.

50. Herreros-Villanueva M, Chen CC, Tsai EM, Er TK. Endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer: What have we learned so far: Clin Chim Acta. 2019;493:63-72.

51. Vercellini P, Fedele L, Aimi G, Pietropaolo G, Consonni D, Crosignani PG. Association between endometriosis stage, lesion type, patient characteristics and severity of pelvic pain symptoms: a multivariate analysis of over 1000 patients. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(1):266-71.

52. Keltz MD, Olive DL. Diagnostic and therapeutic options in endometriosis. Hosp Pract (Off Ed). 1993;28(10A):15-6, 20-2, 31.

53. Kuohung W, Jones GL, Vitonis AF, Cramer DW, Kennedy SH, Thomas D, et al. Characteristics of patients with endometriosis in the United States and the United Kingdom. Fertil Steril. 2002;78(4):767-72.

54. Candiani GB, Fedele L, Vercellini P, Bianchi S, Di Nola G. Repetitive conservative surgery for recurrence of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77(3):421-4.

55. Olive DL, Schwartz LB. Endometriosis. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(24):1759-69.

56. Brosens I. Endometriosis and the outcome of in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2004;81(5):1198-200.

57. Olivennes F. [Results of IVF in women with endometriosis]. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod (Paris). 2003;32(8 Pt 2):S45-7.

58. Vitale SG, La Rosa VL, Rapisarda AMC, Laganà AS. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and psychological well-being. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;38(4):317-9.

59. Nomura S, Suganuma T, Suzuki T, Ito T, Kajiyama H, Okada M, et al. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis during 2 years of estrogen replacement therapy after total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2006;85(8):1019-21.

60. Bernardi LA, Dyson MT, Tokunaga H, Sison C, Oral M, Robins JC, et al. The Essential Role of GATA6 in the Activation of Estrogen Synthesis in Endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2019;26(1):60-9.

61. Halme J, Hammond MG, Hulka JF, Raj SG, Talbert LM. Retrograde menstruation in healthy women and in patients with endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1984;64(2):151-4.

62. Sampson JA. Implantation Peritoneal Carcinomatosis of Ovarian Origin. Am J Pathol. 1931;7(5):423-44.39.

63. Zhao L, Gu C, Ye M, Zhang Z, Han W, Fan W, et al. Identification of global transcriptome abnormalities and potential biomarkers in eutopic endometria of women with endometriosis: A preliminary study. Biomed Rep. 2017;6(6):654-62.

64. Gilabert-Estellés J, Ramón LA, España F, Gilabert J, Vila V, Réganon E, et al. Expression of angiogenic factors in endometriosis: relationship to fibrinolytic and metalloproteinase systems. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(8):2120-7.

65. Ramón L, Gilabert-Estellés J, Castelló R, Gilabert J, España F, Romeu A, et al. mRNA analysis of several components of the plasminogen activator and matrix metalloproteinase systems in endometriosis using a real-time quantitative RT-PCR assay. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(1):272-8.

66. Suda K, Nakaoka H, Yoshihara K, Ishiguro T, Tamura R, Mori Y, et al. Clonal Expansion and Diversification of Cancer-Associated Mutations in Endometriosis and Normal Endometrium. Cell Rep. 2018;24(7):1777-89.

67. Ferguson BR, Bennington JL, Haber SL. Histochemistry of mucosubstances and histology of mixed müllerian pelvic lymph node glandular inclusions. Evidence for histogenesis by müllerian metaplasia of coelomic epithelium. Obstet Gynecol. 1969;33(5):617-25.

68. Sampson JA. Metastatic or Embolic Endometriosis, due to the Menstrual Dissemination of Endometrial Tissue into the Venous Circulation. Am J Pathol. 1927;3(2):93-110.43.

69. Lac V, Nazeran TM, Tessier-Cloutier B, Aguirre-Hernandez R, Albert A, Lum A, et al. Oncogenic mutations in histologically normal endometrium: the new normal? J Pathol. 2019;249(2):173-81.

70. Guo SW. Cancer driver mutations in endometriosis: Variations on the major theme of fibrogenesis. Reprod Med Biol. 2018;17(4):369-97.

71. Borrelli GM, Abrão MS, Taube ET, Darb-Esfahani S, Köhler C, Chiantera V, et al. (Partial) Loss of BAF250a (ARID1A) in rectovaginal deep-infiltrating endometriosis, endometriomas and involved pelvic sentinel lymph nodes. Mol Hum Reprod. 2016;22(5):329-37.

72. Zondervan KT, Rahmioglu N, Morris AP, Nyholt DR, Montgomery GW, Becker CM, et al. Beyond Endometriosis Genome-Wide Association Study: From Genomics to Phenomics to the Patient. Semin Reprod Med. 2016;34(4):242-54.

73. Sapkota Y, Attia J, Gordon SD, Henders AK, Holliday EG, Rahmioglu N, et al. Genetic burden associated with varying degrees of disease severity in endometriosis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2015;21(7):594-602.

74. Sapkota Y, Steinthorsdottir V, Morris AP, Fassbender A, Rahmioglu N, De Vivo I, et al. Meta-analysis identifies five novel loci associated with endometriosis highlighting key genes involved in hormone metabolism. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15539.

75. Rahmioglu N, Montgomery GW, Zondervan KT. Genetics of endometriosis. Womens Health (Lond). 2015;11(5):577-86.

76. Koninckx PR, Kennedy SH, Barlow DH. Pathogenesis of endometriosis: the role of peritoneal fluid. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1999;47 Suppl 1:23-33.

77. McCluggage WG, Bryson C, Lamki H, Boyle DD. Benign, borderline, and malignant endometrioid neoplasia arising in endometriosis in association with tamoxifen therapy. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2000;19(3):276-9.

78. SCOTT RB. Malignant changes in endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 1953;2(3):283-9.

79. Fukunaga M, Nomura K, Ishikawa E, Ushigome S. Ovarian atypical endometriosis: its close association with malignant epithelial tumours. Histopathology. 1997;30(3):249-55.

80. Ballouk F, Ross JS, Wolf BC. Ovarian endometriotic cysts. An analysis of cytologic atypia and DNA ploidy patterns. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;102(4):415-9.

81. Prefumo F, Todeschini F, Fulcheri E, Venturini PL. Epithelial abnormalities in cystic ovarian endometriosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2002;84(2):280-4.

82. Mostoufizadeh M, Scully RE. Malignant tumors arising in endometriosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1980;23(3):951-63.

83. Li Y, Zeng X, Lu D, Yin M, Shan M, Gao Y. Erastin induces ferroptosis via ferroportin-mediated iron accumulation in endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2020.

84. Imanaka S, Yamada Y, Kawahara N, Kobayashi H. A delicate redox balance between iron and heme oxygenase-1 as an essential biological feature of endometriosis. Arch Med Res. 2021.

85. Ito F, Yamada Y, Shigemitsu A, Akinishi M, Kaniwa H, Miyake R, et al. Role of Oxidative Stress in Epigenetic Modification in Endometriosis. Reprod Sci. 2017;24(11):1493-502.

86. Mandai M, Yamaguchi K, Matsumura N, Baba T, Konishi I. Ovarian cancer in endometriosis: molecular biology, pathology, and clinical management. Int J Clin Oncol. 2009;14(5):383-91.

87. Shen H, Fridley BL, Song H, Lawrenson K, Cunningham JM, Ramus SJ, et al. Epigenetic analysis leads to identification of HNF1B as a subtype-specific susceptibility gene for ovarian cancer. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1628.

88. Kobayashi H, Yamada Y, Kawahara N, Ogawa K, Yoshimoto C. Integrating modern approaches to pathogenetic concepts of malignant transformation of endometriosis. Oncol Rep. 2019;41(3):1729-38.

89. Bártů M, Hojný J, Hájková N, Michálková R, Krkavcová E, Hadravský L, et al. Analysis of expression, epigenetic, and genetic changes of HNF1B in 130 kidney tumours. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):17151.

90. Cuff J, Salari K, Clarke N, Esheba GE, Forster AD, Huang S, et al. Integrative bioinformatics links HNF1B with clear cell carcinoma and tumor-associated thrombosis. PLoS One. 2013;8(9):e74562.

91. Ji JX, Wang YK, Cochrane DR, Huntsman DG. Clear cell carcinomas of the ovary and kidney: clarity through genomics. J Pathol. 2018;244(5):550-64.

92. Tate JG, Bamford S, Jubb HC, Sondka Z, Beare DM, Bindal N, et al. COSMIC: the Catalogue Of Somatic Mutations In Cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D941-D7.

93. Mafra F, Mazzotti D, Pellegrino R, Bianco B, Barbosa CP, Hakonarson H, et al. Copy number variation analysis reveals additional variants contributing to endometriosis development. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2017;34(1):117-24.

94. Lowery WJ, Schildkraut JM, Akushevich L, Bentley R, Marks JR, Huntsman D, et al. Loss of ARID1A-associated protein expression is a frequent event in clear cell and endometrioid ovarian cancers. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2012;22(1):9-14.

95. Wiegand KC, Shah SP, Al-Agha OM, Zhao Y, Tse K, Zeng T, et al. ARID1A mutations in endometriosis-associated ovarian carcinomas. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(16):1532-43.

96. Yamamoto S, Tsuda H, Takano M, Tamai S, Matsubara O. Loss of ARID1A protein expression occurs as an early event in ovarian clear-cell carcinoma development and frequently coexists with PIK3CA mutations. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(4):615-24.

97. Yamamoto S, Tsuda H, Takano M, Tamai S, Matsubara O. PIK3CA mutations and loss of ARID1A protein expression are early events in the development of cystic ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. Virchows Arch. 2012;460(1):77-87.

98. Anglesio MS, Bashashati A, Wang YK, Senz J, Ha G, Yang W, et al. Multifocal endometriotic lesions associated with cancer are clonal and carry a high mutation burden. J Pathol. 2015;236(2):201-9.

99. Cornen S, Adelaide J, Bertucci F, Finetti P, Guille A, Birnbaum DJ, et al. Mutations and deletions of ARID1A in breast tumors. Oncogene. 2012;31(38):4255-6.

100. Cheng S, Wang L, Deng CH, Du SC, Han ZG. ARID1A represses hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation and migration through lncRNA MVIH. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;491(1):178-82.

101. Gupta RA, Shah N, Wang KC, Kim J, Horlings HM, Wong DJ, et al. Long non-coding RNA HOTAIR reprograms chromatin state to promote cancer metastasis. Nature. 2010;464(7291):1071-6.

102. Yang Z, Zhou L, Wu LM, Lai MC, Xie HY, Zhang F, et al. Overexpression of long non-coding RNA HOTAIR predicts tumor recurrence in hepatocellular carcinoma patients following liver transplantation. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(5):1243-50.

103. Imai-Sumida M, Dasgupta P, Kulkarni P, Shiina M, Hashimoto Y, Shahryari V, et al. Genistein Represses HOTAIR/Chromatin Remodeling Pathways to Suppress Kidney Cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2020;54(1):53-70.

104. Stamp JP, Gilks CB, Wesseling M, Eshragh S, Ceballos K, Anglesio MS, et al. BAF250a Expression in Atypical Endometriosis and Endometriosis-Associated Ovarian Cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2016;26(5):825-32.

105. Ñiguez Sevilla I, Machado Linde F, Marín Sánchez MDP, Arense JJ, Torroba A, Nieto Díaz A, et al. Prognostic importance of atypical endometriosis with architectural hyperplasia versus cytologic atypia in endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2019;30(4):e63.

106. Katagiri A, Nakayama K, Rahman MT, Rahman M, Katagiri H, Nakayama N, et al. Loss of ARID1A expression is related to shorter progression-free survival and chemoresistance in ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Mod Pathol. 2012;25(2):282-8.

107. Nishikimi K, Nakagawa K, Tate S, Matsuoka A, Iwamoto M, Kiyokawa T, et al. Uncommon Human Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase Promoter Mutations Are Associated With Poor Survival in Ovarian Clear Cell Carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2018;149(4):352-61.

108. Huang HN, Chiang YC, Cheng WF, Chen CA, Lin MC, Kuo KT. Molecular alterations in endometrial and ovarian clear cell carcinomas: clinical impacts of telomerase reverse transcriptase promoter mutation. Mod Pathol. 2015;28(2):303-11.

109. Lin K, Zhan H, Ma J, Xu K, Wu R, Zhou C, et al. Increased steroid receptor RNA activator protein (SRAP) accompanied by decreased estrogen receptor-beta (ER-β) levels during the malignant transformation of endometriosis associated ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Acta Histochem. 2014;116(5):878-82.

110. Theimer CA, Feigon J. Structure and function of telomerase RNA. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16(3):307-18.

111. Andersson S, Wallin KL, Hellström AC, Morrison LE, Hjerpe A, Auer G, et al. Frequent gain of the human telomerase gene TERC at 3q26 in cervical adenocarcinomas. Br J Cancer. 2006;95(3):331-8.

112. Montanaro L, Brigotti M, Clohessy J, Barbieri S, Ceccarelli C, Santini D, et al. Dyskerin expression influences the level of ribosomal RNA pseudo-uridylation and telomerase RNA component in human breast cancer. J Pathol. 2006;210(1):10-8.

113. Nowak T, Januszkiewicz D, Zawada M, Pernak M, Lewandowski K, Rembowska J, et al. Amplification of hTERT and hTERC genes in leukemic cells with high expression and activity of telomerase. Oncol Rep. 2006;16(2):301-5.

114. Yamamoto S, Tsuda H, Takano M, Iwaya K, Tamai S, Matsubara O. PIK3CA mutation is an early event in the development of endometriosis-associated ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. J Pathol. 2011;225(2):189-94.

115. Laudanski P, Szamatowicz J, Kowalczuk O, Kuźmicki M, Grabowicz M, Chyczewski L. Expression of selected tumor suppressor and oncogenes in endometrium of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2009;24(8):1880-90.

116. Matsumoto T, Yamazaki M, Takahashi H, Kajita S, Suzuki E, Tsuruta T, et al. Distinct β-catenin and PIK3CA mutation profiles in endometriosis-associated ovarian endometrioid and clear cell carcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol. 2015;144(3):452-63.

117. Ohba C, Shiina M, Tohyama J, Haginoya K, Lerman-Sagie T, Okamoto N, et al. GRIN1 mutations cause encephalopathy with infantile-onset epilepsy, and hyperkinetic and stereotyped movement disorders. Epilepsia. 2015;56(6):841-8.

118. Catasús L, Bussaglia E, Rodrguez I, Gallardo A, Pons C, Irving JA, et al. Molecular genetic alterations in endometrioid carcinomas of the ovary: similar frequency of beta-catenin abnormalities but lower rate of microsatellite instability and PTEN alterations than in uterine endometrioid carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2004;35(11):1360-8.

119. Burney RO, Talbi S, Hamilton AE, Vo KC, Nyegaard M, Nezhat CR, et al. Gene expression analysis of endometrium reveals progesterone resistance and candidate susceptibility genes in women with endometriosis. Endocrinology. 2007;148(8):3814-26.

120. Fridley BL, Dai J, Raghavan R, Li Q, Winham SJ, Hou X, et al. Transcriptomic Characterization of Endometrioid, Clear Cell, and High-Grade Serous Epithelial Ovarian Carcinoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2018;27(9):1101-9.

121. Tassi RA, Todeschini P, Siegel ER, Calza S, Cappella P, Ardighieri L, et al. FOXM1 expression is significantly associated with chemotherapy resistance and adverse prognosis in non-serous epithelial ovarian cancer patients. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36(1):63.

122. Marquez RT, Baggerly KA, Patterson AP, Liu J, Broaddus R, Frumovitz M, et al. Patterns of gene expression in different histotypes of epithelial ovarian cancer correlate with those in normal fallopian tube, endometrium, and colon. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11(17):6116-26.

123. Khalil AM, Guttman M, Huarte M, Garber M, Raj A, Rivea Morales D, et al. Many human large intergenic noncoding RNAs associate with chromatin-modifying complexes and affect gene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(28):11667-72.

124. Darnell JE. RNA : life's indispensable molecule. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2011.

125. Guttman M, Russell P, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Lander ES. Ribosome profiling provides evidence that large noncoding RNAs do not encode proteins. Cell. 2013;154(1):240-51.

126. Mercer TR, Mattick JS. Structure and function of long noncoding RNAs in epigenetic regulation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20(3):300-7.

127. Moraes F, Góes A. A decade of human genome project conclusion: Scientific diffusion about our genome knowledge. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2016;44(3):215-23.

128. Zhao J, Ohsumi TK, Kung JT, Ogawa Y, Grau DJ, Sarma K, et al. Genome-wide identification of polycomb-associated RNAs by RIP-seq. Mol Cell. 2010;40(6):939-53.

129. Bernstein E, Allis CD. RNA meets chromatin. Genes Dev. 2005;19(14):1635-55.

130. Jeon Y, Lee JT. YY1 tethers Xist RNA to the inactive X nucleation center. Cell. 2011;146(1):119-33.

131. Carey Na. Junk DNA : a journey through the dark matter of the genome.

132. Gutschner T, Diederichs S. The hallmarks of cancer: a long non-coding RNA point of view. RNA Biol. 2012;9(6):703-19.

133. Elliott D, Ladomery M. Molecular biology of RNA. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2011.

134. Spizzo R, Almeida MI, Colombatti A, Calin GA. Long non-coding RNAs and cancer: a new frontier of translational research? Oncogene. 2012;31(43):4577-87.

135. Gibb EA, Brown CJ, Lam WL. The functional role of long non-coding RNA in human carcinomas. Mol Cancer. 2011;10:38.

136. Huarte M, Guttman M, Feldser D, Garber M, Koziol MJ, Kenzelmann-Broz D, et al. A large intergenic noncoding RNA induced by p53 mediates global gene repression in the p53 response. Cell. 2010;142(3):409-19.

137. Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646-74.

138. Liu J, Nie S, Liang J, Jiang Y, Wan Y, Zhou S, et al. Competing endogenous RNA network of endometrial carcinoma: A comprehensive analysis. J Cell Biochem. 2019;120(9):15648-60.

139. Panir K, Schjenken JE, Robertson SA, Hull ML. Non-coding RNAs in endometriosis: a narrative review. Hum Reprod Update. 2018;24(4):497-515.

140. Cohen E, Avrahami D, Frid K, Canello T, Levy Lahad E, Zeligson S, et al. Snord 3A: a molecular marker and modulator of prion disease progression. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e54433.

141. Lanzós A, Carlevaro-Fita J, Mularoni L, Reverter F, Palumbo E, Guigó R, et al. Discovery of Cancer Driver Long Noncoding RNAs across 1112 Tumour Genomes: New Candidates and Distinguishing Features. Sci Rep. 2017;7:41544.

142. Moga MA, Bălan A, Dimienescu OG, Burtea V, Dragomir RM, Anastasiu CV. Circulating miRNAs as Biomarkers for Endometriosis and Endometriosis-Related Ovarian Cancer—An Overview. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2019;8(5).

143. Wang WT, Sun YM, Huang W, He B, Zhao YN, Chen YQ. Genome-wide Long Non-coding RNA Analysis Identified Circulating LncRNAs as Novel Non-invasive Diagnostic Biomarkers for Gynecological Disease. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23343.

144. Moga MA, Bălan A, Dimienescu OG, Burtea V, Dragomir RM, Anastasiu CV. Circulating miRNAs as Biomarkers for Endometriosis and Endometriosis-Related Ovarian Cancer-An Overview. J Clin Med. 2019;8(5).

145. Oikkonen J, Hautaniemi S. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) in precision oncology of ovarian cancer. Pharmacogenomics. 2019;20(18):1251-3.

146. Chen H, Tian X, Luan Y, Lu H. Downregulated Long Noncoding RNA DGCR5 Acts as a New Promising Biomarker for the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Ovarian Cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2019;18:1533033819896809.

147. Li Z, Wei D, Yang C, Sun H, Lu T, Kuang D. Overexpression of long noncoding RNA, NEAT1 promotes cell proliferation, invasion and migration in endometrial endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Biomed Pharmacother. 2016;84:244-51.

148. Hosseini E, Matthieu M, Sabzalipoor H, Kashani H, Nikzad H, Asemi Z. Dysregulated expression of long noncoding RNAs in gynecologic cancers. - PubMed - NCBI. Molecular Cancer. 2017;16(107).

149. Zhao Y, Yang Y, Trovik J, Sun K, Zhou L, Jiang P, et al. A novel wnt regulatory axis in endometrioid endometrial cancer. Cancer Res. 2014;74(18):5103-17.

150. Guo C, Wang X, Chen LP, Li M, Hu YH, Ding WH. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 regulates ovarian cancer cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis through Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2018;22(12):3703-12.

151. Wu L, Wang X, Guo Y. Long non-coding RNA MALAT1 is upregulated and involved in cell proliferation, migration and apoptosis in ovarian cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2017;13(6):3055-60.

152. Sun Q, Li Q, Xie F. LncRNA-MALAT1 regulates proliferation and apoptosis of ovarian cancer cells by targeting miR-503-5p. Onco Targets Ther. 2019;12:6297-307.

153. Tao F, Tian X, Ruan S, Shen M, Zhang Z. miR-211 sponges lncRNA MALAT1 to suppress tumor growth and progression through inhibiting PHF19 in ovarian carcinoma. FASEB J. 2018:fj201800495RR.

154. Lei R, Xue M, Zhang L, Lin Z. Long noncoding RNA MALAT1-regulated microRNA 506 modulates ovarian cancer growth by targeting iASPP. Onco Targets Ther. 2017;10:35-46.

155. Lin Q, Guan W, Ren W, Zhang L, Zhang J, Xu G. MALAT1 affects ovarian cancer cell behavior and patient survival. Oncol Rep. 2018;39(6):2644-52.

156. Wan Y, Chang HY. HOTAIR: Flight of noncoding RNAs in cancer metastasis. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(17):3391-2.

157. Bhan A, Mandal SS. Estradiol-Induced Transcriptional Regulation of Long Non-Coding RNA, HOTAIR. Methods Mol Biol. 2016;1366:395-412.

158. Bhan A, Hussain I, Ansari KI, Kasiri S, Bashyal A, Mandal SS. Antisense transcript long noncoding RNA (lncRNA) HOTAIR is transcriptionally induced by estradiol. J Mol Biol. 2013;425(19):3707-22.

159. Akrami R, Jacobsen A, Hoell J, Schultz N, Sander C, Larsson E. Comprehensive analysis of long non-coding RNAs in ovarian cancer reveals global patterns and targeted DNA amplification. PLoS One. 2013;8(11):e80306.

160. Smolle MA, Bullock MD, Ling H, Pichler M, Haybaeck J. Long Non-Coding RNAs in Endometrial Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(11):26463-72.

161. Nordin M, Bergman D, Halje M, Engström W, Ward A. Epigenetic regulation of the Igf2/H19 gene cluster. Cell Prolif. 2014;47(3):189-99.

162. Kallen AN, Zhou XB, Xu J, Qiao C, Ma J, Yan L, et al. The imprinted H19 lncRNA antagonizes let-7 microRNAs. Mol Cell. 2013;52(1):101-12.

163. Liu SP, Yang JX, Cao DY, Shen K. Identification of differentially expressed long non-coding RNAs in human ovarian cancer cells with different metastatic potentials. Cancer Biol Med. 2013;10(3):138-41.

164. Raveh E, Matouk IJ, Gilon M, Hochberg A. The H19 Long non-coding RNA in cancer initiation, progression and metastasis - a proposed unifying theory. Mol Cancer. 2015;14:184.

165. Cao T, Jiang Y, Wang Z, Zhang N, Al-Hendy A, Mamillapalli R, et al. H19 lncRNA identified as a master regulator of genes that drive uterine leiomyomas. Oncogene. 2019;38(27):5356-66.

166. Matouk IJ, Raveh E, Abu-lail R, Mezan S, Gilon M, Gershtain E, et al. Oncofetal H19 RNA promotes tumor metastasis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1843(7):1414-26.

167. Jing W, Zhu M, Zhang XW, Pan ZY, Gao SS, Zhou H, et al. The Significance of Long Noncoding RNA H19 in Predicting Progression and Metastasis of Cancers: A Meta-Analysis. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:5902678.

168. Ariel I, Weinstein D, Voutilainen R, Schneider T, Lustig-Yariv O, de Groot N, et al. Genomic imprinting and the endometrial cycle. The expression of the imprinted gene H19 in the human female reproductive organs. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1997;6(1):17-25.

169. Chen Y, Wang J, Fan Y, Qin C, Xia X, Johnson J, et al. Absence of the long noncoding RNA H19 results in aberrant ovarian STAR and progesterone production. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2019;490:15-20.

170. Lee C, Kim SJ, Na JY, Park CS, Lee SY, Kim IH, et al. Alterations in Promoter Usage and Expression Levels of Insulin-like Growth Factor-II and H19 Genes in Cervical and Endometrial Cancer. Cancer Res Treat. 2003;35(4):314-22.

171. Liu S, Qiu J, Tang X, Cui H, Zhang Q, Yang Q. LncRNA-H19 regulates cell proliferation and invasion of ectopic endometrium by targeting ITGB3 via modulating miR-124-3p. Exp Cell Res. 2019;381(2):215-22.

172. Zhu Z, Song L, He J, Sun Y, Liu X, Zou X. Ectopic expressed long non-coding RNA H19 contributes to malignant cell behavior of ovarian cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8(9):10082-91.

173. Tanos V, Ariel I, Prus D, De-Groot N, Hochberg A. H19 and IGF2 gene expression in human normal, hyperplastic, and malignant endometrium. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2004;14(3):521-5.

174. Lavie O, Edelman D, Levy T, Fishman A, Hubert A, Segev Y, et al. A phase 1/2a, dose-escalation, safety, pharmacokinetic, and preliminary efficacy study of intraperitoneal administration of BC-819 (H19-DTA) in subjects with recurrent ovarian/peritoneal cancer. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295(3):751-61.

175. Han L, Zhang W, Zhang B, Zhan L. Long non-coding RNA SOX2OT promotes cell proliferation and motility in human ovarian cancer. Exp Ther Med. 2018;15(2):2182-8.

176. Engqvist H, Parris TZ, Rönnerman EW, Söderberg EMV, Biermann J, Mateoiu C, et al. Transcriptomic and genomic profiling of early-stage ovarian carcinomas associated with histotype and overall survival. Oncotarget. 2018;9(80):35162-80.

177. Worku T, Bhattarai D, Ayers D, Wang K, Wang C, Rehman ZU, et al. Long Non-Coding RNAs: the New Horizon of Gene Regulation in Ovarian Cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;44(3):948-66.

178. Mendelsohn Jeoc, Howley PMeoc, Israel MAeoc, Gray JWeoc, Thompson Ceoc. The molecular basis of cancer. Edition 4. ed.

179. Mendelsohn J. The molecular basis of cancer. 3rd ed. ed. Philadelphia, Pa. ; London: Saunders; 2008.

180. Lou Y, Jiang H, Cui Z, Wang X, Wang L, Han Y. Gene microarray analysis of lncRNA and mRNA expression profiles in patients with high‑grade ovarian serous cancer. Int J Mol Med. 2018;42(1):91-104.

181. Liu R, Zeng Y, Zhou CF, Wang Y, Li X, Liu ZQ, et al. Long noncoding RNA expression signature to predict platinum-based chemotherapeutic sensitivity of ovarian cancer patients. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):18.

182. Schwarzenbach H, Stoehlmacher J, Pantel K, Goekkurt E. Detection and monitoring of cell-free DNA in blood of patients with colorectal cancer. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1137:190-6.

183. Gibbs L, Williams S, Weisenfeld N, Craig D, Bassiouni R, Delaney N, et al. Spatial RNA-seq reveals intratumor heterogeneity and transcriptional substructure in high-grade ovarian cancers [abstract]. In: Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the American Association for Cancer Research 2020; 2020 Apr 27-28 and Jun 22-24. Philadelphia (PA): AACR. Cancer Research. 2020;80:NG03.

184. Nerurkar SN, Goh D, Cheung CCL, Nga PQY, Lim JCT, Yeong JPS. Transcriptional Spatial Profiling of Cancer Tissues in the Era of Immunotherapy: The Potential and Promise. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(9).

185. Berglund E, Maaskola J, Schultz N, Friedrich S, Marklund M, Bergenstråhle J, et al. Spatial maps of prostate cancer transcriptomes reveal an unexplored landscape of heterogeneity. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):2419.

186. Thrane K, Eriksson H, Maaskola J, Hansson J, Lundeberg J. Spatially Resolved Transcriptomics Enables Dissection of Genetic Heterogeneity in Stage III Cutaneous Malignant Melanoma. Cancer Res. 2018;78(20):5970-9.

187. Marx V. Method of the Year: spatially resolved transcriptomics. Nat Methods. 2021;18(1):9-14.

188. Soares RJ, Maglieri G, Gutschner T, Diederichs S, Lund AH, Nielsen BS, et al. Evaluation of fluorescence in situ hybridization techniques to study long non-coding RNA expression in cultured cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(1):e4.